Duquesne-class cruiser

Duquesne in her 1939 configuration

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Duquesne class |

| Operators | French Navy |

| Succeeded by | Suffren class |

| Built | 1924–1928 |

| In service | 1929–1962 |

| Building | 2 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Retired | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type |

|

| Displacement | |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 19 m (62 ft 4 in) |

| Draught | 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 34 knots (63 km/h) (designed) |

| Range |

|

| Complement | 605 |

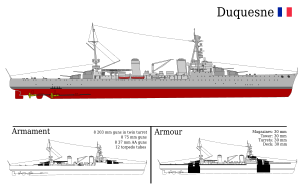

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

| Aircraft carried | 2 FBA 17 and CAMS 37A (superseded by GL-810 then Loire-Nieuport 130 |

| Aviation facilities | 1 catapult |

The Duquesne-class cruiser was a group of two heavy cruisers built for the French Navy in the mid 1920s, the first such vessels built for the French fleet. The two ships in the class were the Duquesne and Tourville.

With the ratification of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, France could not ignore the ramifications of the cruiser article. To maintain her position of a major naval power she would have to follow the other four major naval powers with her own 10,000-ton, 8-inch gun cruiser.[2] The only modern cruiser design Service techniques des constructions navales (STNC - Constructor's Department)[3] had to draw on was the recently designed 8,000-ton Duguay-Trouin-class design. The cruiser design authorized under the 1924 build program would sacrifice protection for speed while maintaining the 10,000-ton displacement restriction while mounting 8 inch guns.[4] Two vessels would be authorized and would be known as the Duquesne-class cruiser.

Initially classed as a light cruiser, both ships were reclassified on 1 July 1931 as first class cruisers. The French Navy did not have a vessel classification of heavy cruiser instead used armoured cruiser and light cruiser prior to the London Naval Treaty then first class cruiser and second class cruiser afterwards.[5]

Design and description[edit]

Hull and protection[edit]

The design was an enlargement of the Duguay-Trouin-class light cruiser with standard displacement raised to 10,000 tons. The hull was lengthened to a length between perpendiculars of 185 meters (606 ft 11 in) with an overall length of 191 meters (626 ft 8 in) and a beam of 19 meters (62 ft 4 in). The framing in a French hull was numbered from aft to stem, therefore frame no 1 would be the aft perpendicular frame with the frames being numbered by the distance in meters from the aft perpendicular. With the increase of the standard displacement to 10,160 metric tons (10,000 long tons), the draft of the ship would increase to 6.45 meters (21 ft 2 in).[6]

The protection was minimal as in the previous Duguay-Trouin class and was minimally increased by 50 percent in the Duquesne class using the same armour layout. Protection over the magazines was 30 mm (1.2 in) with 20 mm (0.79 in) crowns, the protective deck would be 30 mm (1.2 in). The conning tower and turrets would be 30 mm (1.2 in). The hull was divided by 16 bulkheads into 17 watertight compartments. The walls of the transverse bulkheads at each end of the machinery spaces was increased to 20 mm (0.79 in) to limit flooding to three compartments for mine or torpedo hits. Each compartment would be watertight from keel to main deck with its own pumps and ventilation. The steering gear was protected with 17 mm (0.67 in) plates.[7]

Machinery[edit]

To maintain the 10,000-ton limitation the STNC determined that using the same machinery at the previous class would have put the ships at 200 tons over the limit to achieve the 34 knot speed desired. The STNC therefore put the machinery out for bid. AC Bretagne came up with an eight boiler four shaft solution producing 155,000 CV for 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) at normal displacement. The ships would be equipped with eight Guyot du Temple small tube boilers built by Indret rated at 20 kg/cm2 (280 psi) while operating at 215 °F (102 °C) setup in four boiler rooms. The forward two rooms would feed the forward engine room and vent through the forward funnel. The midships boiler rooms would feed the aft engine room and vent through the aft funnel. Four identical single reduction gear Rateau-Bretagne stem turbines would produce the 120,000 CV (chevaux - horses)* to achieve the required speed. Two cruising turbines were fitted to the inboard shafts to achieve the 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) requirement.[8] The boilers would be oil fired with a maximum load of 1,842 tons of oil giving an endurance of 5,000 nmi at 15 knots, 1,800 nmi (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) at 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph) and 700 nmi (1,300 km; 810 mi) at 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph).[9] The ships would have two centerline rudders. The first would be 11 square meters (120 sq ft) and the aft rudder would be twice as large at 22 m2 (240 sq ft). They had a large tactical radius as with all French ships of this period.[10]

Armament[edit]

The requirement of a main armament of eight 203-millimetre (8 in) guns housed in three or four lightly armoured turrets with magazine storage of 150 rounds per gun[11] was made more difficult as the French had no 203 mm gun in their inventory.[12] A new gun was designed with a simplistic constructed of a thick autofretted A tube, with a shrunk jacket and breach ring. The gun was bored to 20.30 cm (7.99 in) with a length of 50 calibers. The breach was sealed using a Welin-type interrupted screw breach that open upwards. The weapon was designated as the 203 mm/50 (8 in) Model 1924 naval gun. The guns were mounted in four Cruiser Two Gun Turret Model 1924 providing a separation of the axis of the guns by 74 inches. The turret was plated with two sheets of 15 mm high tensile steel plate riveted together placed on all sides and roof for armour protection of 30 mm. The mount provided an elevation from minus 5 degree to plus 45 degrees with an elevation rate of ten degrees per second. The mount could be trained to plus or minus 90 degrees from the centerline of the vessel with a train rate of six degrees per second. The guns could be loaded at any degree of train but only between minus 5 and plus ten degrees in elevation. The loading cycle started with the rammer cocked by the recoil of the guns. A dredger hoist brought the shell and two half charge bags to the breech. The rammer drove the shell into the breech with the powder being loaded by hand. The breech would close and the gun would be fired. The guns could maintain a rate of fire of four to five rounds per minute. At maximum elevation an APC 1927 shell with a two half charges totaling 53 kilograms (117 lb) had a range of 31,400 meters (34,300 yd) with a muzzle velocity of 850 m/s (2,800 ft/s). The APC M1936 shell with two half charges totaling 47 kg (104 lb) had a range of 30,000 m (33,000 yd) with a muzzle velocity of 820 m/s (2,700 ft/s). In 1939 the APC M1936 shell had a dye bag with a specific colour for each ship. Duquesne was red, Tourville was Yellow and Suffren was green.[13][14]

The Staff Requirement for the secondary armament was for four 100 mm high angle guns with 500 rounds.[15] Due to weight restrictions this was reduced to eight 75 mm/50 (2.95 inch) model 1922 naval gun on single Model 1922 gun mounts. The mount provided an elevation of minus 10 degrees to plus 90 degrees with the loading angle for high elevation being limited to plus 75 degrees. Training angles were plus/minus 150 degrees from the beam of the vessel. The used fixed ammunition with a sliding breech and were capable of eight to fifteen rounds per minute.[16][17] The medium anti-aircraft armament was augmented with eight 37 mm/50 (1.46 inch) model 1925 guns in eight Model 1925 single mounts. With an elevation only to plus 85 degrees they had a slow rate of fire, 15 to 21 rounds per minute therefore were not effective against modern aircraft when installed.[18] These guns would be replaced with single 40 mm Bofors as the equipment became available. To complete the light AA armament it was intended to install four single 8 mm Hotchkiss machineguns on the quarterdeck just aft of the last 203 mm turret. However, it was recognized that these weapons were ineffective against aircraft of the period so they were replaced by twelve 13,2 mm (0.5 inch) Model 1929 machine guns. Two would be mounted forward on the lower bridge wings and the other four in place of the 8mm machine guns. These guns would be mounted in twin mountings.[19] In 1943 they were replaced by 20 mm Oerlikon cannons based on the availability of the equipment.

For torpedoes the Staff Requirement was for two quadruple launchers with four spare torpedoes.[20] Again due to weight limitations this was reduced to two triple launchers. The two launchers of a new type Model 1925T for 550 mm torpedoes were fitted to port and starboard. When in the locked position the starboard launcher faced forward and the port launcher faced aft. The tubes could be trained and fired either locally or from the armoured conning tower. The ships initially carried the 55 cm (21.65 inch) 23DT, Toulon torpedo. Nine torpedoes were carried, six in the tubes with three spares.[21] The torpedo tubes were landed between 1943 and 1945.[22]

Aircraft[edit]

The aircraft handling arrangements would not be an add-on affair as it had been on the Duguay-Trouin class. Initially two obsolete float planes, FBA 17 and the CAMS 37A would be carried. The aircraft would not be catapult launched but lowered on to the surface of the water to take off. The catapult was finally installed in 1929 - 1930 and the obsolete aircraft replaced by the Gordou-Lesseurre float plane. The catapult was installed between the fore funnel and the mainmast with one aircraft on the catapult and the other on the boat deck. Two aircraft would be carried until 1937 when the catapult was removed for modification. Once the modification was complete the catapult was reinstalled with a Loire 130 float plane. The aircraft and catapults would be removed for good between 1943 and 1945.[23]

Ships[edit]

| Ship name[24] | Launched[25] | In Service[26] | Out of Service[27] | Fate[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duquesne | 17 December 1925 | 25 January 1929 | 2 July 1955 | Sales List 27 July 1956 |

| Tourville | 24 August 1926 | 12 March 1929 | 4 March 1962 | Towed for scrapping 15 January 1963 |

History[edit]

Duquesne and Tourville during the interwar period she served in the Mediterranean Sea while taking periodic cruises to show the Flag. During the war Duquesne was on blockade duty in the mid-Atlantic whereas Tourville was in the Mediterranean Sea. Both became part of Force X at Alexandria prior to Italy's entry into the war where they were interned for three years after the French Armistice with Germany.[29] With the German occupation of Vichy France in November 1942 thereby nullifying the Armistice of 1940 the ships of Force X joined the Free French Forces on 17 May 1943. They sailed for Dakar via the Suez Canal in July.[30] Again assigned to blockade duty in the Mid Atlantic at Dakar; but their anti-aircraft protection was still considered inadequate to provide gunfire support for the invasion of Normandy. Duquesne was part of the French Naval Task Force formed in December 1944 to bombard pockets of German resistance on the French Atlantic coast. Post war both aided in the restoration of French Colonial rule in French Indochina until placed in reserve in 1947. Duquesne remained in reserve until condemned for disposal in 1955 whereas Tourville remained in reserve until condemned for disposal in 1962.[31]

Note[edit]

- all ship statistical data from French Cruisers 1922 - 1956 (Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Duquesne and Tourville, Design and Construction, Building Data and General Characteristics) unless otherwise noted

- French sources do not use shaft horsepower rating for the power output of their machinery. Instead the term 'chevaux' (CV) or horses is used. To convert the French measure to SHP multiply the CV value by 0.98632 to find the true SHP value. Jane's did not do this nor has many of the English language sources. The reference French Cruisers 1922 - 1056 shows the horse power values as only CV and gives the value for conversion to SHP used in many sources.

-

Duquesne in original anti-surface layout

-

Tourville after refit at Bizerte: changed anti-air armament, removal of sea plane, torpedo launchers and aft mast

-

Tourville in 1929

References[edit]

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 29

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Duquesne and Tourville

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Acronyms and Abbreviations

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 29

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 9, Cruiser Designations

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Building Data and General Characteristics

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Protection

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Design and Construction

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Building Data and General Characteristics

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Ground Tackle and Navigation

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Design and Construction

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 29

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Armament, Main Battery

- ^ Nav Weapons, France, 203 mm/50

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Design and Construction

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Armament, Anti-aircraft Weapons

- ^ Nav Weapons, France, 75 mm/50

- ^ Nav Weapons, France, 37 mm/50

- ^ Nav Weapons, France, 13.2 mm

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Duquesne and Tourville, Design and Construction

- ^ Nav Weapons, France, French Pre-War Torpedoes

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Armament, Torpedoes

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 2, Armament, Aviation Installations

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 30

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 30

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 30

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 12, The Deactivation of Cruisers

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 12, The Deactivation of Cruisers

- ^ Whitley, Duquesne Class, p. 30

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 10, The Forces of North Africa rejoin the Allied Cause

- ^ Jordan & Moulin, Chapter 12, The Deactivation of Cruisers

Bibliography[edit]

- Auphan, Paul; Mordal, Jacques (1959). The French Navy in World War II. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- Jordan, John (2005). "Duquesne and Tourville: The First French Treaty Cruisers". Warship 2005. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-84486-003-5.

- Jordan, John & Moulin, Jean (2013). French Cruisers 1922–1956. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-133-5.

- le Masson, Henri (1969). Navies of the Second World War: The French Navy 1. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

- McMurtrie, Francis E. (1940). Jane's Fighting Ships 1940. London, UK: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd.

- Preston, Antony (2002). The World's Worst Warships. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-754-6.

- Truebe, Carl (September 2017). "Question 26/45". Warship International. LIV (3): 184, 186. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Whitley, M.J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two – An International Encyclopedia. London, UK: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-225-1.