Ebbo Gospels

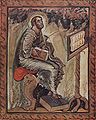

| St. Mark's illustration | |

|---|---|

St. Mark's illustration from the Ebbo Gospels | |

| Year | c. 816-35 |

| Owner | Municipal Library (Epernay, France) |

The Ebbo Gospels (Épernay, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 1) is an early Carolingian illuminated Gospel book known for its illustrations that appear agitated. The book was produced in the ninth century at the Benedictine Abbaye Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers, by Ebbo, the archbishop of Reims.[1] Its style influenced Carolingian art and the course of medieval art.[2] The Gospels contains the four gospels by Saint Mark, Saint Luke, Saint John, and Saint Matthew, along with their illustrations containing symbolism and iconography.[1] The evangelists illustrations reflect an expressive art style called Emotionalism, that has a stylistic relationship with the Utrecht Psalter and the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram.[2] In comparison to the Utrecht Psalter and the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, the Ebbo Gospels demonstrates very energetic lines and dimension, in contrast to the Classical Roman art style of the past.[3]

History

[edit]The making of the Ebbo Gospels was during the Carolingian Renaissance, when Charlemagne was crowned the Holy Roman emperor by the Pope in the year 800.[4] Charlemagne had the goal of incorporating more Christian and Roman ideology within Europe as he was inspired by Constantine, who ruled c. 306-33, and made it more acceptable to practice Christianity.[5]

After the fall of Rome, Charlemagne later became emperor to spread the word of Christianity and revive ancient Roman arts. He commissioned many Gospels and manuscripts including the Ebbo Gospels to help educate people and preserve ancient Roman art. These Christian manuscripts aided the way Charlemagne believed Christianity should be practiced.[6]

Provenance

[edit]The Ebbo Gospels was produced in the ninth century at the Benedictine Abbaye Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers,[7] which was one of the earliest manuscripts from Hautillers to not be destroyed or lost.[8] The Ebbo Gospels was produced by the school of Rheims and given to Ebbo, an archbishop of Rheims from c. 816–835 to 840-841, by Abbot Peter of Hautvillers before Ebbo was deposed. [1] The Gospel book may have been made for his return as archbishop in 840-841 during Charlemagne's son Louis I, reign as emperor.[7][9] The book is now currently in the Municipal Library in Épernay, France.[4]

Description

[edit]The Ebbo manuscript is a lavish codex and holds great value, being it was commissioned by the emperor Charlemagne. [10][11] Each page is 10 in by 8 in,[7] with details of gold ink. The vellum of the codex is dyed purple to correlate with the colors of royalty.[7][4] For the Ebbo Gospel to be easier to read and more legible than localized script, Charlemagne created a script called Carolingian Miniscule, based on Roman letters that aided in easier education. [5][11]

The Gospel book contains a poem to Ebbo (also spelled Ebo).[7] The Ebbo Gospel focus is the four gospels of the new testament and depicts the four evangelists Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John in illustration.[12] In the foreground of the illustration depicting Matthew in the Ebbo Gospels, Matthew is sitting down wearing Roman clothing with his feet outstretched on his foot stool. His face is very expressive as he leans forward using the tools such as an ink horn (left hand), which contained ink, and a stylus (right hand) to create his gospel book with his blank codex.[4][10][1] In the background, in the upper right corner, Matthew's symbol, an angel or a man with wings, is holding a scroll. The Roman architecture of classic Byzantine and nature landscape is present in the background.[1]

St. Mark's illustration represents him seated in a Roman stool, twisting his body to look upwards towards his symbol of a lion that is holding a scroll. His clothing consists of many lines, shadows, and highlights. Mark's facial expression is relaxed as he dips his stylus in ink to prepare for writing, in the inscribed codex rested on his leg.

In St. Luke's illustration he is sitting down looking at his symbol of an ox with his codex, ink horn, and stylus rested in his lap. Another codex is inscribed on a stand in front of Saint Luke, but his eyes are only directed towards his symbol.

St. John is illustrated as an older man with a beard, with his head surrounded by a halo. His body is twisted as he looks at his symbol of an eagle to his left, and holds a long scroll across his body.

-

St. John's illustration in Ebbo Gospels

-

St. Luke illustration in Ebbo Gospels

Style

[edit]The Ebbo Gospels style was curated by scholars, artists, and writers in a workshop at Rheims school, who were hired by Charlemagne to study Roman art and replicate it.[1] Greek artists fleeing the Byzantine iconoclasm of the 8th century brought this style to Aachen and Reims to be able to depict iconography.[2]

The illustrations have roots in late classical painting; landscapes are represented in an illusionistic style,[4] as a reflection of Roman culture and the landscapes are represented in an illusionistic style.[10] The Roman influences within the art is shown within the clothing drapery, replicating the clothes of Roman philosophers in the illustration, as well as the Byzantine architecture in the background, heavily representing Rome.[5]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

The emotionalism, however, was new to Carolingian art and distinguishes the Ebbo Gospels from classical art.[2]

Classical art was more naturalistic in replicating the human figure,[4] while the art present in the Ebbo Gospels focused more on art style. Figures such as evangelists are made with swift brush strokes that demonstrate energy, represented in nervous, agitated poses using a streaky style with swift brush strokes. In the 1st Century in Europe, the idea of an enthusiastic prophet was prevalent.[13] This energy is reflected with the quick lines and Matthews eager body language to write having for god.

The artists make use of perspective by adding a foreground and background. The use of three-dimensional space is demonstrated by the depiction of shadows and highlights, the coloring of the sky, furniture, and the architecture in the back.[4] The skewed proportions such as St. Matthews unbalanced look represent the evangelists are from another world and hold great power.

Iconography and symbolism

[edit]Each of the evangelist created one gospel, and their symbols correlate to the gospel contents.[3] Matthew is a winged-man, which connects to his gospel containing information about Gods possible relation to king David. Mark's symbol is a lion because of his crying resembling a lions roar. Luke's gospel discusses sacrifice, which correlates to his symbol an ox that connects to Christ's involvement with sacrifices, and John represents an eagle in his gospel, because eagles are able to get close to heaven. St. John also has a halo in his illustration that represents him being very holy.[14] The Ebbo Gospels represent the "Anruftypus" style of iconography, meaning the evangelists are able to look up at their symbols. [15] The eye contact of the saints towards the symbols allude to a connection. In the illustrations of all evangelists their symbols are holding handscrolls which creates more of a connection between the evangelists and their symbol.

Similar manuscripts

[edit]The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram is a manuscript made in 870 following the Ebbo Gospels style.[16] Although, the Utrecht Psalter is the most famous example made in the same Reims school.[2] The Utrecht Psalters style possibly influenced Carolingian art with its rapid strokes, was an influence for classical art, and the course of medieval art.

Historians have noted the similarity between the Utrecht Psalter and the Ebbo Gospels. The evangelist portrait of Matthew in the Ebbo Gospels is similar to the illustration of the psalmist in the first psalm of the Utrecht Psalter.[7] The Carolingian art could be the interpretation of the Utrecht Psalter Classical style that has quick and rapid brush-strokes.[4]

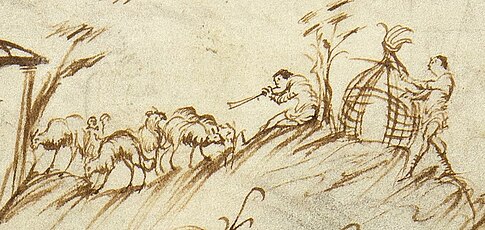

Other images in the Ebbo Gospels appear to be based on distortions of drawings which may have been from the Utrecht Psalter. [7] Goldschmidt, a medieval historian, claims that many of the small details of the Utrecht Psalter can be compared to the features of the Ebbo Gospels.[17] Items such the ink, the way animals are depicted, architecture is illustrates, body language and gestures that people in these books are given, has some connection between both the Ebbo Gospels and the Psalter.

"In short, we find not one thing, whether it is a stool with a lion's head and claws, or an inkwell, whether it is the lance or the arrow of the warrior, the lions, the birds, the buildings, the figures, and the gestures that cannot be paralleled to the smallest detail in style as well as in content, in the Utrecht Psalter."

— Goldschmidt, Gertrude R. Benson, "New light on the origin of the Utrecht Psalter" (1931), p. 23.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Carolingian Manuscripts Part 2: Ebbo Gospels. Retrieved 2024-04-22 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b c d e Berenson, Ruth (1966). "The Exhibition of Carolingian Art at Aachen". Art Journal. 26 (2): 160–165. doi:10.2307/775040. ISSN 0004-3249.

- ^ a b "Smarthistory – How to recognize the Four Evangelists". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ross, Nancy (December 10, 2015). "Smarthistory – Saint Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c "Smarthistory – Carolingian art, an introduction". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Smarthistory – Charlemagne (part 2 of 2): The Carolingian revival". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chazelle, Celia (1997). "Archbishops Ebo and Hincmar of Reims and the Utrecht Psalter". Speculum. 72 (4): 1055–1077. doi:10.2307/2865958. ISSN 0038-7134.

- ^ Moore, R. I. (1997). "Review of Relics, Apocalypse, and the Deceits of History: Ademar of Chabannes, 989- 1034". Speculum. 72 (3): 850–852. doi:10.2307/3040807. ISSN 0038-7134.

- ^ McKeon, Peter R. (1974). "Archbishop Ebbo of Reims (816-835): A Study in the Carolingian Empire and Church". Church History. 43 (4): 437–447. doi:10.2307/3164920. ISSN 0009-6407.

- ^ a b c "Matthew in the Coronation Gospels and Ebbo Gospels (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b Sorabella, Jean (December 2008). "Carolingian Art".

- ^ Nees, Lawrence (2012). "Ebbo Gospels".

- ^ Moffitt, John F. (2005-01-01), "Post-Classical and Christian "Inspiration"", Inspiration: Bacchus and the Cultural History of a Creation Myth, Brill, pp. 94–128, doi:10.1163/9789047407027_009, ISBN 978-90-474-0702-7, retrieved 2024-04-22

- ^ Haring, Walter (1922). "The Winged St. John the Baptist Two Examples in American Collections". The Art Bulletin. 5 (2): 35–40. doi:10.2307/3046430. ISSN 0004-3079.

- ^ Alexander, J. J. G. (1966). "A Little-Known Gospel Book of the Later Eleventh Century from Exeter". The Burlington Magazine. 108 (754): 6–16. ISSN 0007-6287.

- ^ Calkins, Robert G. (1986). Illuminated books of the Middle Ages. Cornell paperbacks (1. print ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9377-5.

- ^ Benson, Gertrude R. (1931). "New Light on the Origin of the Utrecht Psalter: I: The Latin Tradition and the Reims Style in the Utrecht Psalter". The Art Bulletin. 13 (1): 13–79. doi:10.1080/00043079.1931.11409295. ISSN 0004-3079.

- Benson, Gertrude R. (March 1931). "New light on the origin of the Utrecht Psalter". The Art Bulletin. 13 (1): 13–79. doi:10.1080/00043079.1931.11409295. JSTOR 3045474.

- Berenson, Ruth (Winter 1966–1967). "The Exhibition of Carolingian art at Aachen". Art Journal. 26 (2): 160–165. doi:10.2307/775040. JSTOR 775040.

- Calkins, Robert G. (1983). Illuminated books of the middle ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9377-3.

- Biggs, Sara J. (2013). Bringing our medieval manuscripts to life

- Chazelle, Celia (October 1997). "Archbishops Ebo and Hincmar of Reims and the Utrecht Psalter". Speculum. 72 (4): 1055–1077. doi:10.2307/2865958. JSTOR 2865958.

- Haring, Walter (1922). "The Winged St. John the Baptist Two Examples in American Collections". The Art Bulletin. 5 (2): 35–40. doi:10.2307/3046430. ISSN 0004-3079.

- McKeon, Peter R. (1974). "Archbishop Ebbo of Reims (816-835): A Study in the Carolingian Empire and Church". Church History. 43 (4): 437–447. doi:10.2307/3164920. ISSN 0009-6407.

- Moffitt, John F. (2005), "Post-Classical and Christian "Inspiration"", Inspiration: Bacchus and the Cultural History of a Creation Myth, Brill, pp. 94–128, doi:10.1163/9789047407027_009, ISBN 978-90-474-0702-7

- Moore, R. I. (1997). "Review of Relics, Apocalypse, and the Deceits of History: Ademar of Chabannes, 989- 1034". Speculum. 72 (3): 850–852. doi:10.2307/3040807. ISSN 0038-7134.

- Ross, Nancy, Carolingian Art Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Smarthistory, undated

- Ross Nancy & Freeman, Jennifer A. (2015). "Saint Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels." Smarthistory. https://smarthistory.org/saint-matthew-from-the-ebbo-gospels/.