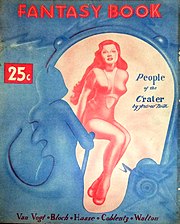

Fantasy Book

Fantasy Book was a semi-professional[note 1] American science fiction magazine that published eight issues between 1947 and 1951. The editor was William Crawford, and the publisher was Crawford's Fantasy Publishing Company, Inc. Crawford had problems distributing the magazine, and his budget limited the quality of the paper he could afford and the artwork he was able to buy, but he attracted submissions from some well-known writers, including Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, A. E. van Vogt, Robert Bloch, and L. Ron Hubbard. The best-known story to appear in the magazine was Cordwainer Smith's first sale, "Scanners Live in Vain", which was later included in the first Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology, and is now regarded as one of Smith's finest works. Jack Gaughan, later an award-winning science fiction artist, made his first professional sale to Fantasy Book, for the cover illustrating Smith's story.

Publication history

[edit]| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | 1/1 | |||||||||||

| 1948 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | |||||||||

| 1949 | 1/5 | |||||||||||

| 1950 | 1/6 | 2/1 | ||||||||||

| 1951 | 2/2 | |||||||||||

| Issues of Fantasy Book, showing volume and issue number. The magazine lists a year of

issue; the months of issue are taken from later bibliographies.[2] | ||||||||||||

The first science fiction (SF) magazine, Amazing Stories, appeared in 1926, and by the mid-1930s SF pulp magazines were a well-established genre. In 1933, William Crawford, a Pennsylvania science fiction fan, started Unusual Stories, a semi-professional SF magazine, and he followed this with Marvel Tales in 1934. Neither of the magazines lasted long or achieved wide distribution, though he obtained stories from Clifford Simak, P. Schuyler Miller, and John Wyndham, all of whom were established writers. After World War II, Crawford, by now living in Los Angeles, founded Fantasy Publishing Company, Inc., and in 1947 he launched Fantasy Book in bedsheet format.[3] The editor was listed as "Garret Ford"; this was a pseudonym for Crawford and his wife, Margaret. Some additional editorial work was done by Forrest Ackerman.[2]

By the time the first issue was printed in mid-1947, Crawford's distributor had gone out of business, leaving him with 1,000 copies on hand. He attempted to sell the issue through subscription and placed some for sale via specialist dealers.[3] Crawford did not always have access to high-quality paper,[3] and he decided to produce two versions of the second issue: one on book-quality paper, priced at 35 cents, and another on lower-quality paper, priced at 25 cents, intended for newsstand distribution, each featuring different cover artwork.[2][4][5] The third and fourth issues were also produced in two versions with different covers, and the same price difference.[5] With the third issue, Crawford reduced the size to digest, announcing, "The change in size may be inconvenient to some collectors—but it has become a question of a small FB or no FB at all".[6]

The lack of a reliable distributor continued to be a problem; Crawford commented in the fourth issue that he had still not obtained reliable nationwide distribution for the magazine.[6] The remaining issues were all in digest format, except for issue 6, which shrank to a small digest size. The eighth and final issue appeared in January 1951.[2]

Contents and reception

[edit]

Crawford still had in inventory stories he had acquired for Marvel Tales over a decade earlier, and "People of the Crater" by Andre Norton (under the pseudonym Andrew North), which appeared in the first issue, was one of these.[3] There was also a story by A. E. van Vogt, "The Cataaaa",[7] and Robert Bloch's "The Black Lotus",[8] which had first appeared in 1935 in Unusual Stories.[9] Crawford's budget limited the quality of the artwork he could acquire—he sometimes was unable to pay for art—but he managed to get Charles McNutt, later better known as Charles Beaumont, to contribute interior illustrations to the first issue.[3] Wendy Bousfield, a science fiction historian, describes his work as "strikingly original",[10] and considers the first issue to be the most artistically attractive of the whole run.[10]

The next two issues featured covers by Lora Crozetti on the de luxe editions; sf historian Mike Ashley considers both to be "appalling",[3] and Bousfield describes them as "crude and uninspired".[10] Van Vogt appeared in both issues, with "The Ship of Darkness" and "The Great Judge", and the second issue featured the first installment of The Machine-God Laughs, by Festus Pragnell, which was serialized over three issues.[3] The fourth issue saw the beginning of another serial: Black Goldfish, by John Taine (a pseudonym for the mathematician Eric Temple Bell); it ran for two issues. Bousfield describes both serials as "among the weakest stories FB published". A third serial, Journey to Barkut, by Murray Leinster, began in the seventh issue and was left incomplete when the magazine ceased publication. It subsequently appeared in full in Startling Stories in 1952.[8]

L. Ron Hubbard, shortly to become the founder of Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology, contributed "Battle of the Wizards" to issue 5, and the sixth issue saw two notable stories. One was "The Little Man on the Subway", by Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl, under the pseudonym "James MacCreigh"; Asimov had rewritten Pohl's first draft and submitted it to John Campbell at Unknown in 1941, who had rejected it. The other was "Scanners Live in Vain", by Cordwainer Smith. This was a pseudonym for Paul A. Linebarger, a professor of Asian politics and a military advisor, who had written the story, inspired by his knowledge of psychology, some years before; he tried to sell it to the leading SF magazines during the war, but had been rejected.[11] The story was Smith's first sale, and is now regarded as a classic—SF critic John Clute describes it as "one of [Smith's] finest works",[12] Pohl said that "it is perhaps the chief reason why [Fantasy Book] is remembered",[13] and it was later included in the first volume of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies voted on by members of the Science Fiction Writers of America.[14][15] Jack Gaughan, later an award-winning artist in the field, provided the cover for issue 6; it was his first professional sale.[16][11] Bousfield considers it the only "truly outstanding" cover of the magazine's run.[10]

SF critics Malcolm Edwards and Peter Nicholls describe Fantasy Book as "generally an undistinguished and erratic magazine",[4] but Ashley comments that small-press magazines such as Fantasy Book, by providing an outlet for stories that could not sell elsewhere, provided a valuable service to the genre.[17]

Bibliographic details

[edit]All eight issues of the Fantasy Book were published by Fantasy Publishing Company, Inc. (FPCI), of Los Angeles, and edited by "Garret Ford", a pseudonym for William and Margaret Crawford. The first two issues were in bedsheet format, and the remaining issues in digest format, except for issue 6 which was a small digest. The first two issues were 44 pages long; the next two were 68 pages; issues 5 and 6 were 84 pages and 112 pages respectively; the last two issues were both 82 pages. The price was 25 cents for all issues except for the three de luxe variant editions of issues 2, 3, and 4, which were 35 cents.[2]

Two anthologies were drawn mostly or entirely from the stories published in Fantasy Book. In 1949, Crawford anonymously edited The Machine-God Laughs, which contained Pragnell's story and two more stories from Fantasy Book.[18] It was published by Griffin Publishing, which was owned by Crawford.[18][19] In 1953, Crawford's other publishing company, FPCI, issued Science and Sorcery, edited by "Garret Ford", the pseudonym used by the Crawfords when they edited Fantasy Book. It contained fifteen stories, nine of which had originally appeared in Fantasy Book.[18]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A semiprofessional magazine, or "semiprozine", is a magazine that lies somewhere between an amateur fanzine and a full professional magazine. For science fiction magazines, the definition has been codified by the World Science Fiction Society (the body that administers the Hugo Awards) since 1983, and requires that the magazine meet two of the following criteria: it must "have an average press run of at least 1000 copies; pay its contributors and/or staff in other than copies of the publication; provide at least half the income of any one person; have at least 15% of its total space occupied by advertising; or announce itself to be a semiprozine."[1]

References

[edit]- ^ Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike; Langford, David. "Culture : Semiprozine : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bousfield (1985), p. 264.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ashley (2000), p. 212.

- ^ a b Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter. "Culture : Fantasy Book : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Stephensen-Payne, Phil. "Fantasy Book". www.philsp.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Bousfield (1985), p. 258.

- ^ Bousfield (1985), p. 261.

- ^ a b Bousfield (1985), p. 262.

- ^ Ashley & Contento (1995), p. 122.

- ^ a b c d Bousfield (1985), p. 259.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 213.

- ^ Clute, John. "Authors : Smith, Cordwainer : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (December 1966). "Cordwainer Smith". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. Vol. 25, no. 2. p. 6.

- ^ Langford, David; Nicholls, Peter. "Culture : Nebula Anthologies : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "Publication: The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One". www.isfdb.org. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Gustafson, Jon; Langford, David. "Authors : Gaughan, Jack : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b c Bousfield (1985), p. 263.

- ^ Clute, John; Edwards, Malcolm. "Authors : Crawford, William L : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike; Contento, William (1995). Supernatural Index: A Listing of Fantasy, Supernatural, Occult, Weird, and Horror Anthologies. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24030-2.

- Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1920–1954. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13679-X.

- Bousfield, Wendy (1985). "Fantasy Book". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 258–264. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Fantasy fiction magazines

- Magazines established in 1947

- Magazines disestablished in 1951

- Defunct science fiction magazines published in the United States

- Magazines published in Los Angeles

- Science fiction magazines established in the 1940s

- 1947 establishments in California

- 1951 disestablishments in California