Goose Tatum

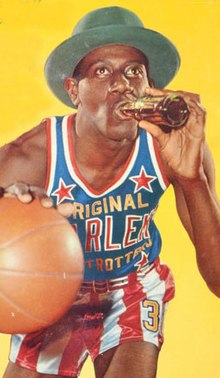

Tatum on a Coca-Cola advertisement, 1954 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 31, 1921[a] El Dorado, Arkansas, US[a] |

| Died | January 18, 1967 (aged 45) El Paso, Texas, US |

| Resting place | Fort Bliss National Cemetery |

| Education | Booker T. Washington High School (El Dorado, Arkansas) |

| Occupation(s) | professional basketball and baseball player, entertainer, World War II Veteran |

| Years active | 1937–1943, 1946–1966 |

| Sport | |

| Sport | baseball (1937–1943, 1946–49), basketball (1941–42, 1946–1966) |

| Team | Louisville Black Colonels (1937) Memphis Red Sox (1941) Birmingham Black Barons (1942) Harlem Globetrotters (1941–42, 1946–1954) Indianapolis Clowns (1943, 1946–49) Harlem Magicians / Stars / Trotters / Roadkings (1953–1966) Detroit Stars (unknown) |

Reece "Goose"[1] Tatum (May 31, 1921[a] – January 18, 1967) was an American Negro league baseball and basketball player. In 1942, he was signed to the Harlem Globetrotters and had an 11-year career with the team. He later formed his own team known as the Harlem Magicians with former Globetrotters player Marques Haynes. He is a member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. Tatum's number 50 is retired by the Globetrotters.

Biography[edit]

Reece "Goose" Tatum was born in El Dorado, Arkansas on May 31, 1921[a] to Ben and Alice Tatum. Ben Tatum was a farmer and part-time preacher, and Alice Tatum was a domestic cook. The fifth of seven children, Reece Tatum attended Booker T. Washington High School in El Dorado, Arkansas, where he was a three-sport star in baseball, basketball and football. It is not known if he graduated.[2]

After high school, Tatum pursued a career in professional baseball and joined the Louisville Black Colonels in 1937. He played for the Memphis Red Sox and the Birmingham Black Barons in 1941 and 1942, respectively.[2] Tatum served in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II.[3]

Harlem Globetrotters owner and coach Abe Saperstein signed Tatum in 1942. Tatum was released by the Globetrotters in 1955 after 11 seasons. At the time of his release, he was making a reported $53,000 per year, which The Detroit Tribune noted was the highest salary made by a professional basketball player. Saperstein told the press Tatum's release was due to his violation of team rules and repeated absences from games.[4]

Tatum and Marques Haynes, who were both Harlem Globetrotters players, formed a barnstorming basketball team of their own: The Fabulous Harlem Magicians. Dempsey Hovland, owner of 20th Century Booking Agency, was recruited to book the Harlem Magicians' games. Hovland earlier had managed the barnstorming House of David basketball team.

Personal life and legal incidents[edit]

In February 1955, Tatum filed a lawsuit against the owners of the San Francisco, California based Pan-American Bar for refusing to serve him, his wife and three companions on account of their race. Tatum was asking for $13,000 in damages.[5] Tatum was arrested in Gary, Indiana in November 1955 for non-payment of alimony. He allegedly owed his ex-wife $7,000 in alimony and was ordered by Judge Anthony Roszkowski to pay $60 a week pending a final judgment.[6]

Tatum was married briefly to Lottie 'the Body' Graves who he met in San Francisco.[7]

Death and legacy[edit]

In 1966, Tatum's son, Goose Jr., was killed in a car accident. Soon after, Tatum began drinking heavily, which led to a series of hospital visits. He died at his home in El Paso, Texas on January 18, 1967, at the age of 45.[2] The official autopsy stated that he died of natural causes. Tatum was interred in the Fort Bliss National Cemetery.

Tatum has been described as the original "clown prince"—a term first applied to seminal Chicago Crusader/Philadelphia Giant Jackie Bethards in 1933[8]—of the Trotters. He wove numerous comic routines into his play, many of which achieved a cult following. Some of these routines were based on his stature—at 6'4", he reportedly had an arm span of approximately 84 inches (210& cm) and could touch his kneecaps without bending. Tatum is credited with inventing the hook shot.[2] While playing for the Harlem Magicians, Tatum was billed as having scored the most points in the history of basketball, but the assertion is dubious.[9]

In 1974, Tatum was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. His number 50 jersey was retired by the Harlem Globetrotters on February 8, 2002 and his name was placed on the Globetrotters' "Legends Ring" at Madison Square Garden in New York City.[2] Tatum was the fourth player to have his number retired by the Globetrotters. In 2011, he was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.[10][11]

Footnotes[edit]

- a Some sources list Tatum's birth date as May 3, 1921, in Hermitage, Arkansas.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ Lederer, Richard (March 1, 1994). "The names of the games". The Telegraph.

- ^ a b c d e f Scott, Nikki. "Reece "Goose" Tatum (1921–1967)". encyclopediaofarkansas.net. The Central Arkansas Library System. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ "Negro Leaguers Who Served With The Armed Forces in WWII". baseballinwartime.com. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "Released by 'Trotters; Plans Team". The Detroit Tribune. Detroit, Michigan. April 30, 1955. p. 5. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ "Athlete Sues Bar; Asks $13,000". Madera Tribune. Vol. 63, no. 251. Madera, California. United Press International. February 2, 1955. p. 2. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ "Goose Tatum Gets Cooked". The Detroit Tribune. Detroit, Michigan. November 26, 1955. p. 5. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Klein, Sarah (August 3, 2005). "Paradise Regained". Detroit Metro Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Among Our Colored Citizens". Times. Chester, Pennsylvania. December 8, 1933.

- ^ "The Harlem Stars Will Be in Town on Mon., Mar. 9". The Detroit Tribune. Detroit, Michigan. March 7, 1959. p. 5. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ "Coronation for Basketball’s Clown Prince," by Oscar Robertson, The New York Times, August 6, 2011

- ^ Jeff Zillgitt (August 12, 2011). "Goose Tatum, Globetrotters' clown prince, is bound for Hall". USA Today.

External links[edit]

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference and Seamheads

- 1921 births

- 1967 deaths

- African-American baseball players

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- Baseball players from Arkansas

- Basketball players from Arkansas

- Birmingham Black Barons players

- Cincinnati Clowns players

- Detroit Stars players

- Harlem Globetrotters players

- Indianapolis Clowns players

- Memphis Red Sox players

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- Sportspeople from El Dorado, Arkansas

- United States Army Air Forces soldiers

- African-American United States Army personnel

- American men's basketball players

- 20th-century African-American sportspeople

- African Americans in World War II