Hanafi school

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Arabic. (August 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The Hanafi school or Hanafism (Arabic: ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنَفِيّ, romanized: al-madhhab al-ḥanafī) is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam.[1] It was established by the 8th-century scholar, jurist, and theologian Abu Hanifa (c. 699–767 CE), a follower whose legal views were primarily preserved by his two disciples Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani.[2] As the oldest and most-followed of the four major Sunni schools, it is also called the "school of the people of opinion" (madhhab ahl al-ra'y).[3][4] Many Hanafis also follow the Maturidi school of theology.

It encompasses not only the rulings and sayings of Abu Hanifa, but also the rulings and sayings of the judicial council he established.[citation needed] Abu Hanifa was the first to formally solve cases and organize them into chapters.[citation needed] He was followed by Malik ibn Anas in arranging Al-Muwatta. Since the Sahaba and the successors of the Sahaba did not put attention in establishing the science of Sharia or codifying it in chapters or organized books, but rather relied on the strength of their memorization for transmitting knowledge, Abu Hanifa feared that the next generation of the Muslim community would not understand Sharia laws well.[ambiguous] His books consisted of Taharah (purification), Salat (prayer), other acts of Ibadah (worship), Muwamalah (public treatment), then Mawarith (inheritance).[3]

Under the patronage of the Abbasids, the Hanafi school flourished in Iraq and spread throughout the Islamic world, firmly establishing itself in Muslim Spain and Greater Iran, including Greater Khorasan, by the 9th century, where it acquired the support of rulers including Delhi Sultanate, Khwarazmian Empire, Kazakh Sultanate and the local Samanid rulers.[5] Turkic expansion introduced the school to the Indian subcontinent and Anatolia, and it was adopted as the chief legal school of the Ottoman and Mughal Empire.[6] In the modern Republic of Turkey, the Hanafi jurisprudence is enshrined in The Directorate for Religious Affairs of Türkiye (Turkish:Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı. The name is shortened as Diyanet, TCDİB, DİB), through the constitution (art. 136).[7]

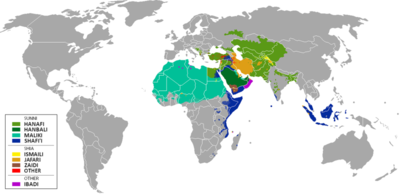

The Hanafi school is the largest of the four traditional Sunni schools of Islamic jurisprudence, followed by approximately 30% of Sunni Muslims worldwide.[8][9] It is the main school of jurisprudence in the Balkans, Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, the Levant, Central Asia and South Asia, in addition to parts of Russia and China.[10][11] The other primary Sunni schools are the Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali schools.[12][13]

One who ascribes to the Hanafi school is called a Hanafi, Hanafite or Hanafist (Arabic: ٱلْحَنَفِيّ, romanized: al-ḥanafī, pl. ٱلْحَنَفِيَّة, al-ḥanafiyya or ٱلْأَحْنَاف, al-aḥnāf).

History

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (November 2023) |

A standardized legal tradition (madhhab) did not exist among early Muslims.[vague] To them, the only sources of Sharia were the Quran and the Sunnah.[citation needed] If not found in these two sources, they had to reach consensus, and early Muslims differed in their interpretation of religious matters. At the end of the era of the Companions,[when?] the Tabi'is found solutions by adopting different ways to interpret Islamic Shari'ah. Thus, the formula for establishing the Islamic Shari'ah was prepared by the Sahaba and the Tabi'is.[citation needed] At the end of the Tabi'i period, the expansion of the Islamic empire meant that legal experts felt the need to give the Shari'ah a scientific form—Fiqh—which Abu Hanifa did by creating a unique methodology.[vague] At the same time he also established the Aqidah as an individual religious science.[citation needed]

Ja'far al-Sadiq, a descendant of Muhammad was one of the teachers of Abu Hanifah and Malik ibn Anas who in turn was a teacher of Al-Shafi‘i,[14][15]: 121 who, in turn, was a teacher of Ahmad ibn Hanbal. Thus all of the four great Imams of Sunni Fiqhs are connected to Ja'far directly and indirectly.[16]

The core of Hanafi doctrine was compiled in the 3rd Hijri century and has been gradually developing since then.[17]

The Abbasid Caliphate and most of the Muslim dynasties were some of the earliest adopters of the relatively more flexible Hanafi fiqh and preferred it over the traditionalist Medina-based Fiqhs, which favored correlating all laws to Quran and Hadiths and disfavored Islamic law based on discretion of jurists.[18] The Abbasids patronized the Hanafi school from the 2nd Hijri century onwards. The Seljuk Turkish dynasties of 5th and 6th Hijri centuries, followed by Ottomans and Mughals, adopted Hanafi Fiqh. The Turkic expansion spread Hanafi Fiqh through Central Asia and into Indian subcontinent, with the establishment of Seljuk Empire, Timurid dynasty, several Khanates, Delhi Sultanate, Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Empire. Throughout the reign of 77th Caliph and 10th Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and 6th Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, the Hanafi-based Al-Qanun and Fatawa-e-Alamgiri served as the legal, juridical, political, and financial code of most of West and South Asia.[17][18]

Genesis of Madhhab

[edit]Duration

[edit]Scholars commonly define the formative period of the Hanafi school as starting with Abu Hanifa's judicial research (d. 767 CE/150 AH) and concluding with the death of his disciple Hasan bin Ziyad (d. 820 CE/204 AH).[19]

This stage is concerned with the foundation of the Madhhab and its establishment, the formation of principles and bases upon which orders are determined and branches arises. Abu Zuhra, a prominent 20th century Egyptian Islamic jurist suggested, "The work would have been done by the Imam himself. And under his guidance, his senior students would participated in it. Abu Hanifa had a unique "discussions and debate" method to conduct on the issues until they were settled. If resolved, Abu Yusuf would have been ordered to codify it."[20]

Work

[edit]Explaining the method of Abu Hanifa in teaching his companions, Al-Muwaffaq Al-Makki says, “Abu Hanifa established his doctrine by consultation among them. He never possess the rulings arbitrarily without them. He was diligent in practicing religion and exaggerated in advising about God, His Messenger and the believers. He would pick up questions one by one and present to them. He would hear what they had and say what he had. Debates would have continued with them for a month or more until one of the sayings was settled in it. Then Judge Abu Yusuf would formulate the principle from that, thus, he formulated all the principles.”[21] Accordingly, the students of Abu Hanifa were participants in the establishment of this jurisprudential structure, they were not just listeners, accepting what was presented to them. And Abu Yusuf was not the only one who recorded what the opinion settled on, but in the circle of Abu Hanifa there were ten blogging,[clarification needed] headed by the four big ones: Abu Yusuf, Muhammad bin Al-Hassan Al-Shaibani, Zufar bin Al-Hudhayl and Hassan bin Ziyad al-Luluii.[22]

Methodology

[edit]| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Including:

|

Hanafi usul recognises the Quran, hadith, consensus (ijma), legal analogy (qiyas), juristic preference (istihsan) and normative customs (urf) as sources of the Sharia.[2][23] Abu Hanifa is regarded by modern scholars as the first to formally adopt and institute qiyas as a method to derive Islamic law when the Quran and hadiths are silent or ambiguous in their guidance;[24] and is noted for his general reliance on personal opinion (ra'y).[2]

The islamic jurists are usually viewed as two groups: Ahl al-Ra'y (The people of personal opinion) and Ahl al-Hadith (The People of Hadith). The jurists of the Hanafi school are often accused of preferring ra'y over hadith. Muhammad Zahid al-Kawthari says in his book Fiqh Ahl al-`Iraq wa Hadithuhum: "Ibn Hazm thinks of the jurists as Ahl al-Ray and Ahl al-Hadith. This differentiation has no basis and is without a doubt only the dream of some exceptional people, that have been influenced by the statements of some ignorant narrators, after the mihna of Ahmad bin Hanbal." He also states that the Hanafis could only be called Ahl al-Ray, because of how talented and capable they are when it comes to ra'y. And not because of their lack of knowledge in hadith or them not relying on it, as the term Ahl al-Ray usually implies.[25]

Regardless of their usage of Ra'y as one of the sources of their jurisprudence, the Hanafite scholars still prioritize the textual approach of the Sahaba. Careful examination by modern Islamic jurisprudence researcher Ismail Poonawala has found that the influence of the hadiths narrated by Zubayr regarding Rajm (stoning) execution as a form of punishment towards adulterers was within Abu Hanifa's rulings in the Hanafite school of thought for such kinds of punishments' validity and furthermore, how to implement the punishment in accordance with Muhammad's teachings due to self-confession of the accused.[Notes 1]

The Hanafite law has had a profound influence on the implementation of Hanafite laws from the late medieval to modern period, including:

- Fatawa 'Alamgiri: Fatawa 'Alamgiri is an Islamic edict book first implemented as state law in India during the reign of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[28] Later, the British Raj also implemented this law in an effort to better control their Indian Muslim subjects.[28]

- Qanun: The Ottoman Empire through their Qanun law which is not dissimilar from Fatawa 'Alamgiri was formed and canonized as state law by Suleiman the Magnificent.[29][30] This law indirectly influenced their ally, the Sultanate of Aceh, who also had its own version of Rajm (stoning) law in their law codex.[31] This codex even became the autonomical legal codex of modern-day Aceh province, as the province recognizes Sharia law based on Qanun which they call Qanun Jinayat.[32] This Hanafite law of Rajm (stoning) in Aceh has survived to the 21st century as it was officially recognized by the Indonesian government in 2014, in addition to the Selangor state of Malaysia recognizing it in 1995 as an autonomical law,[33] The fundamentalist Taliban faction also reportedly follow their own variant of Hanafi Qanun.[34]

The foundational texts of Hanafi madhab, credited to Abū Ḥanīfa and his students Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani, include Al-Fiqh al-Akbar (book on theology), Al-fiqh al-absat (book on theology), Kitab al-Athar (thousands of hadiths with commentary), Kitab al-Kharaj and the so called Zahir ar-Riwaya, which are six books in which the authoritative views of the founders of the school are compiled. They are Al-Mabsut (also known as Kitab al-Asl), Al-Ziyadat, Al-Jami' al-Saghir, Al-Jami' al-Kabir, Al-Siyar al-Saghir and Al-Siyar al-Kabir (doctrine of war against unbelievers, distribution of spoils of war among Muslims, apostasy and taxation of dhimmi).[35][36][37]

Istihsan

[edit]The Hanafi school favours the use of istihsan, or juristic preference, a form of ra'y which enables jurists to opt for weaker positions if the results of qiyas lead to an undesirable outcome for the public interest (maslaha).[38] Although istihsan did not initially require a scriptural basis, criticism from other schools prompted Hanafi jurists to restrict its usage to cases where it was textually supported from the 9th-century onwards.[39]

Dispersion of followers

[edit]It is estimated that up to 30% of Muslims in the world follow the Hanafi school. Today, most followers of the Hanafi school live in Turkey, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, China, Syria, Jordan, Uzbekistan,Tajikistan, Afghanistan, India, Egypt, Albania, Kosovo, Cyprus and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Also, a limited number of followers of this school live in Iran, Azerbaijan, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, and Iraq.[40][41][42][43][44]

List of Hanafi scholars

[edit]- Abd al-Ghani al-Ghunaymi al-Maydani

- Abu Hafs Umar al-Nasafi

- Abu Hanifa

- Abu Mansur al-Maturidi

- Abu Yusuf

- Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi

- Ali al-Qari

- Al-Tahawi

- Amjad Ali Aazmi

- Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani

- Džemaludin Čaušević

- Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi

- Hasan Moglica

- Ibn Abidin

- Khadim Hussain Rizvi

- Muhammad Abdullah Ghazi

- Muhammad al-Shaybani

- Muhammad Idrees Dahri

- Muneeb-ur-Rehman

- Nasr Abu Zayd

- Shafee Okarvi

- Yahya ibn Ma'in

See also

[edit]- Darul Uloom Deoband

- Islamic schools and branches

- Maturidi

- List of major Hanafi books

- List of Hanafis

- The four Sunni Imams

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ramadan, Hisham M. (2006). Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary. Rowman Altamira. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-0-7591-0991-9.

- ^ a b c Warren, Christie S. "The Hanafi School". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b Eid, Muhammad (5 June 2015). "المذهب الحنفي… المذهب الأكثر انتشاراً في العالم". Masjid Salah al-Din (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Al-Haddad, Husam (17 November 2014). "المذهب الحنفي.. المذهب الأكثر انتشاراً". Islamist Movements (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ Hallaq, Wael (2010). The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 9780521005807.

- ^ Hallaq, Wael (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0521678735.

- ^ "Türki̇ye Büyük Mi̇llet Mecli̇si̇" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "Jurisprudence and Law – Islam". Reorienting the Veil. University of North Carolina (2009).

- ^ "Hanafi School of Law – Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ a b Siegbert Uhlig (2005), "Hanafism" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha, Vol. 2, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447052382, pp. 997–99

- ^ Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad (2010), Theory and Practice of Modern Islamic Finance, ISBN 978-1599425177, pp. 77–78

- ^ Gregory Mack, "Jurisprudence", in Gerhard Böwering et al. (2012), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691134840, p. 289

- ^ "An Introduction to Hanafi Madhhab". www.islamawareness.net. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ Dutton, Yasin, The Origins of Islamic Law: The Qurʼan, the Muwaṭṭaʼ and Madinan ʻAmal, p. 16

- ^ Haddad, Gibril F. (2007). The Four Imams and Their Schools. London, the UK: Muslim Academic Trust. pp. 121–194.

- ^ "Imam Ja'afar as Sadiq". History of Islam. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2012. "Imam Ja'afar as Sadiq | History of Islam". Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ a b Nazeer Ahmed, Islam in Global History, ISBN 978-0738859620, pp. 112–14

- ^ a b John L. Esposito (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195107999, pp. 112–14

- ^ Ibrahim, Muhammad; Bin Muhammad, Ali (2012). المذهب عند الحنفية والمالكية والشافعية والحنابلة (in Arabic) (45th ed.). Kuwait: Al-Waei Al-Islami. p. 36.

- ^ Zidan, Abdul Karim (2000). المدخل لدراسة الشريعة الإسلامية (in Arabic). p. 157.

- ^ Muhammad, Ali Juma (2012). كتاب المدخل إلى دراسة المذاهب الفقهية (in Arabic) (4th ed.). Dar al-Salam. p. 118.

- ^ المذهب عند الحنفية. p. 48.

- ^ Hisham M. Ramadan (2006), Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0759109919, p. 26

- ^ See:

*Reuben Levy, Introduction to the Sociology of Islam, pp. 236–37. London: Williams and Norgate, 1931–1933.

*Chiragh Ali, The Proposed Political, Legal and Social Reforms. Taken from Modernist Islam 1840–1940: A Sourcebook, p. 280. Edited by Charles Kurzman. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2002.

*Mansoor Moaddel, Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse, p. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

*Keith Hodkinson, Muslim Family Law: A Sourcebook, p. 39. Beckenham: Croom Helm Ltd., Provident House, 1984.

*Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, edited by Hisham Ramadan, p. 18. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

*Christopher Roederrer and Darrel Moellendorf, Jurisprudence, p. 471. Lansdowne: Juta and Company Ltd., 2007.

*Nicolas Aghnides, Islamic Theories of Finance, p. 69. New Jersey: Gorgias Press LLC, 2005.

*Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pp. 89–113. 1974 - ^ "Fiqh-u-Ahl-il-IRAQ".

- ^ Abū Ḥanīfah & Poonawala (2002, p. 450)

- ^ Abdul Karim Da'wah al-Husaini, Hamad (2006). المدينة المنورة في الفكر الإسلامي [Madinah al-Munawwarah in Islamic thought] (in Arabic). Dar al-Kotob Ilmiyah. p. 106. ISBN 9782745149343. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ a b Baillie & Elder (2009, pp. 1–3 with footnotes)

- ^ Punar (2016, p. 20)

- ^ an Naim Na (2009, pp. 35–39, 76–79, 97)

- ^ "Relasi Aceh Darussalam dan Kerajaan Utsmani, Sebuah Perspektif" [The Relationship between Aceh Darussalam and the Ottoman Empire, A Perspective]. Aceh institute. info@acehinstitute.org. 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Cammack & Feener (2012, p. 42)

- ^ Harahap (2018)

- ^ Rahimi, Haroun (2021). A Constitutional Reckoning with The Taliban's Brand of Islamist Politics: The Hard Path Ahead. Peace Studies. Vol. VIII. Kabul, Afghanistan: Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-9936-655-15-7. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Oliver Leaman (2005), The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415326391, pp. 7–8

- ^ Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- ^ Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

- ^ "Istihsan". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Hallaq, Wael (2008). A History of Islamic Legal Theories: An Introduction to Sunnī Uṣūl al-Fiqh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0521599863.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Sri Lanka: Information on whether there is a Hanafi Muslim community in Sri Lanka, and on its origin, numerical strength and where the majority of its members are located". Refworld. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Ahmady, Kameel (2023). From Border to Border Comprehensive research study on identity and ethnicity in Iran. Moldova: Scholars’ Press publishes.

- ^ "Abu Hanifah | Biography, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Di Maio, Micah; Abenstein, Jessica (2011). "Policy Analysis: Tajikistan's Peacebuilding Efforts Through Promotion of Hanafi Islam". Journal of Peacebuilding & Development. 6 (1): 75–79. doi:10.1080/15423166.2011.950863228443. ISSN 1542-3166. JSTOR 48603036. S2CID 111103531.

- ^ "Will you give information about which madhhab is common in which country?".

Works cited

[edit]- Abū Ḥanīfah, Nuʻmān ibn Muḥammad; Poonawala, Ismail (2002). The Pillars of Islam: Muʻāmalāt: laws pertaining to human intercourse. Translated by Asaf Ali Asghar Fyzee. Oxford University Press. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-19-566784-4. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Baillie, Neil; Elder, Smith (2009). A digest of the Moohummudan law. London. pp. 1–3 with footnotes. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cammack, Mark E.; Feener, R. Michael (2012). "The Islamic Legal System in Indonesia" (PDF). Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal. 21 (1).

- Harahap, Cempaka Sari (2018). "Hukuman Bagi Pelaku Zina (Perbandingan Qanun No. 6 Tahun 2014 tentang Hukum Jinayat dan Enakmen Jenayah Syariah Negeri Selangor No. 9 Tahun 1995 Seksyen 25)" [Punishment for Adultery Perpetrators (Comparative Qanun No. 6 of 2014 concerning the Law of Jinayat and the Crime of Sharia Crimes in Selangor State No. 9 of 1995 Section 25)]. Hukum Fiqih(Fiqh Law). 4 (2). Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- an Naim Na, Abdullahi Ahmed (2009). Islam and the Secular State Negotiating the Future of Shari'a. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-26144-0. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Punar, Bunyamin (2016). "Kanun and Sharia: Ottoman Land Law in Şeyhülıslam Fatwas From Kanunname of Budın to the Kananname-İ Cedıd". A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of İstanbul Şehir University. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Branon Wheeler, Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Ḥanafī Scholarship (Albany, SUNY Press, 1996).

- Nurit Tsafrir, The History of an Islamic School of Law: The Early Spread of Hanafism (Harvard, Harvard Law School, 2004) (Harvard Series in Islamic Law, 3).

- Behnam Sadeghi (2013), The Logic of Law Making in Islam: Women and Prayer in the Legal Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Chapter 6, "The Historical Development of Hanafi Reasoning", ISBN 978-1107009097

- Theory of Hanafi law: Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- Hanafi theory of war and taxation: Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

- Burak, Guy (2015). The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Ḥanafī School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-09027-9.

External links

[edit]- Hanafiyya Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- Kitab al-siyar al-saghir (Summary version of the Hanafi doctrine of War)[dead link] Muhammad al-Shaybani, Translator – Mahmood Ghazi

- The Legal Aspects of Marriage according to Hanafi Fiqh Archived 22 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Islamic Quarterly London, 1985, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 193–219

- Al-Hedaya[dead link], A 12th century compilation of Hanafi fiqh-based religious law, by Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani, Translated by Charles Hamilton

- Development of family law in Afghanistan: The role of the Hanafi Madhhab Central Asian Survey, Volume 16, Issue 3, 1997