Solander Islands

Māori: Hautere | |

|---|---|

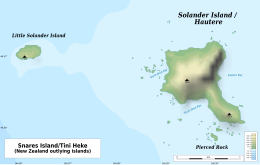

Map of the Solander Islands | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southland District |

| Coordinates | 46°34′S 166°53′E / 46.567°S 166.883°E |

| Area | 120 ha (300 acres) |

| Length | 1.6 km (0.99 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 330 m (1080 ft) |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

| Additional information | |

| Age Pleistocene [1] Arc volcano | |

The Solander Islands / Hautere are three eroded remnants volcanic islets towards the western enterance of the Foveaux Strait just beyond New Zealand's South Island. The islands lie 40 km (25 mi) south of the coastline of Fiordland.[2]

The islands are andesite rocks with the tip being a larger submerged stratovolcano,[3] roughly equivalent in size to Mount Taranaki.[4][5] It was formerly believed that the volcano last erupted roughly 2 million years ago, but in 2008 radiometric dating of rock samples from the main island found that it was between 150,000 and 400,000 years old.[1] In 2013 it was discovered that Little Solander Island had been active even more recently at between 20 and 50,000 years ago.[6]

Administratively, the islands form part of Southland District, making them the only uninhabited outlying island group of New Zealand to be part of a local authority.

Islands

[edit]Solander Island / Hautere (also known in Māori as Te Niho a Kewa), the main island,[7] covers around 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi), rising steeply to a peak 330 metres (1,083 ft) above sea level. It is wooded except for its northeast end, mainly a bare, white rock. A deep cave is on the east side, Sealers Cave. Little Solander Island is 1.9 km (1.2 mi) west. It reaches 148 m (486 ft) high yet covers 4 ha (9.9 acres). It has a barren appearance and is guano-covered. Pierced Rock is 250 m (273 yd) south of the main island. It rises to 54 m (177 ft) and covers 2,000 m2 (22,000 sq ft) (0.2 ha).

Administratively, the islands form part of Southland District, making them the only uninhabited outlying island group of New Zealand to be part of a local authority.

History

[edit]

The Māori name for the summit of Solander Island is Pukekohu, and the side of the summit is known in Māori as Pukepari.[8] "Hautere" is the father of Moko, a Ngāti Kurī chief, who notably murdered a Kāti Māmoe chief called Tūtewaimate.[9][10]

The island chain was sighted by Captain James Cook on 11 March 1770 and named by him after the Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander, one of the scientific crew aboard Cook's ship, Endeavour.[11]

The islands are geographically forbidding and weather conditions often confound the approach of ships, dissuading attempts at permanent habitation. Australian sealers briefly made use of the islands during the early 19th century, likely living on small flats between the island's cliffs and its shoreline for stints of a few months.[12] Castaways would occasionally end up on the islands, and in 1813, a passing ship bound for Stewart Island found five men in need of rescue. The men – four Europeans and one Australian Aboriginal – were marooned there between 1808 and 1813, representing the longest continuous period of habitation on the islands. They are thought to have been left ashore in two groups for seal hunting (sealing), but the sea prevented the approach of any ship to recover them. In 1810, sealing moved to Macquarie Island, farther to the west, and they were effectively abandoned. When rediscovered in 1813, it is likely that they had amassed many dried seal pelts.[12]

Geology

[edit]The islands are remnants of an isolated extinct trachyandesite and andesite Pleistocene volcano whose volcanics have geochemical affinities with modern adakites.[13][14] The andestic dome of Little Solander Island was active between 20 and 50,000 years ago.[6] The age of the main island is 150 to 400 thousand years old, backed up by pollen data, with in one set of analysis the eruptives having a mean age of 344 ± 10 ka and another mean age of 247 ± 8 ka.[6][1] The islands lie on a bank with depths less than 100 m (328 ft), separated from the continental shelf along Foveaux Strait by a 4 km (2.5 mi) but narrow trough 200 m (656 ft) deep (at least 237 m or 778 ft). Therefore, the islands are included in the New Zealand Outlying Islands.

The islands are the only volcanic land in New Zealand recently related to the subduction of the Australian Plate beneath the Pacific Plate[1][15] along the Puysegur Trench, which extends southwards from the end of the Alpine Fault.[16] The current estimated rate of subduction is 35–36 mm per year.[13] The Solander Basin Mesozoic continental basement rock consists of diorite and subordinate gabbro overlaid by Oligocene to Pliocene sediment.[13] This is isotopically distinct continental crust from the Solander Islands, excluding partial melting of the lower crust as creating the volcanic magma.[14] It has been suggested that the melt that formed the islands comes from a peridotitic source enriched by the addition of a slab-derived melt with subsequent open-system fractionation, resulted in the evolved andesitic adakites.[14]

Flora and fauna

[edit]There are 53 vascular plant species, one third of which are very rare. The flora is dominated by ferns and orchids. The southern, and nominate, subspecies of Buller's albatross (Thalassarche b. bulleri) breeds only on the Solanders and the Snares.

The Solander Islands were historically a well-known area for migrating whales, especially southern right and sperm whales. Sperm whales in this area were said to be exceptionally large.[17]

Bird life

[edit]The islands are home to a variety of bird life.[18]

The Solander group has been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because of its significance as a breeding site for Buller's albatrosses (with about 5000 pairs) and common diving petrels.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mortimer, N.; Gans, P.B.; Mildenhall, D.C. (2008). "A middle-late Quaternary age for the adakitic arc volcanics of Hautere (Solander Island), Southern Ocean". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 178 (4): 701–707. Bibcode:2008JVGR..178..701M. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.09.003. ISSN 0377-0273.

- ^ Mortimer, N. (2013). "Geology and Age of Solander Volcano, Fiordland, New Zealand". Journal of Geology. 121 (5): 475–487. Bibcode:2013JG....121..475M. doi:10.1086/671397.

- ^ "Global Volcanism Program | Hautere". Smithsonian Institution | Global Volcanism Program. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Keith; Nodder, Scott D.; Carter, Lionel (12 June 2006). "Sea floor geology - Active plate boundaries". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Solander Island – an extinct volcano". Science Learning Hub. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Mortimer, N.; Gans, P.B.; Foley, F. V.; Turner, M. B.; Daczko, N.; Robertson, M.; Turnbull, I. M. (2013). "Geology and Age of Solander Volcano, Fiordland, New Zealand". Journal of Geology. 121 (5): 475–487. Bibcode:2013JG....121..475M. doi:10.1086/671397. S2CID 140662244.

- ^ "Te Ara-a-Kiwa: How Foveaux Strait came to be according to Māori legend". The Southland Times. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Roberts, W.H.S (1910). "Maori Nomenclature: Early history of Otago". Otago Daily Times. Dunedin, New Zealand. p. 40.

- ^ Beattie, J.H (1949). The Maoris and Fiordland: Māori myths, fascinating fables, legendary lore, typical traditions and native nomenclature. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago Daily Times. p. 19.

- ^ Beattie, J.H (1944). "Māori place-names of Otago: hundreds of hitherto unpublished names with numerous authentic traditions / told by the Maoris to Herries Beattie". Otago Daily Times. Dunedin, New Zealand. p. 76.

- ^ Lee, Garry J. "Science on the Map: Places in New Zealand Named After Scientists". The Rutherford Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b McNab, Robert (1905). Murihiku: A History of the South Island of New Zealand and the Islands Adjacent and Lying to the South, from 1642 to 1835. Cambridge University Press (republished 2011). pp. 208–211. ISBN 9781108039994. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Foley, Fiona V.; Pearson, Norman J.; Rushmer, Tracy; Turner, Simon; Adam, John (2013). "Magmatic Evolution and Magma Mixing of Quaternary Adakites at Solander and Little Solander Islands, New Zealand". Journal of Petrology. 54 (4): 703–744. doi:10.1093/petrology/egs082.

- ^ a b c Foley, Fiona V.; Turner, Simon; Rushmer, Tracy Rushmer; Caulfield, John T.; Daczko, Nathan R.; Bierman, Paul; Robertson, Matthew; Barrie, Craig D.; Boyce, Adrian J. (2014). "10Be, 18O and radiogenic isotopic constraints on the origin of adakitic signatures: a case study from Solander and Little Solander Islands, New Zealand". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 168 (1048). Bibcode:2014CoMP..168.1048F. doi:10.1007/s00410-014-1048-9. S2CID 129879486.

- ^ Keith Lewis, Scott D. Nodder and Lionel Carter. 'Sea floor geology – Solander Island', Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 21 September 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ "Alpine Fault". www.otago.ac.nz. Department of Geology, Otago University. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Rhys Richards (2010), Sperm whaling on the Solanders Grounds and in Fiordland: A marine historian's perspective (PDF), National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Wikidata Q125945903

- ^ O'Donnell, Colin F.J. "Birds and mammals of Solander (Hautere) Island." Notornis 27: 21-44" (PDF). Notornis vol. 27). pp. 21–44.

- ^ BirdLife International. (2012). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Solander Islands. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 27 January 2012.

- Wise's New Zealand guide: A gazetteer of New Zealand (4th ed.) (1969) Dunedin: H. Wise & Co. (N.Z.) Ltd.

External links

[edit]- Geology

- Botany

- Fauna (Albatrosses)

- Nautical information

- NZ map viewer Archived 11 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- photo

- Islands of the Southland Region

- New Zealand outlying islands

- Volcanoes of the New Zealand outlying islands

- Pleistocene volcanoes

- Extinct volcanoes

- Important Bird Areas of New Zealand

- Volcanic islands of New Zealand

- Uninhabited islands of New Zealand

- Foveaux Strait

- Islands of the New Zealand outlying islands

- Stratovolcanoes of New Zealand