Hu Zhengyan

Hu Zhengyan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

One of Hu Zhengyan's personal seals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 1584 Xiuning, China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | c. 1674 (aged 89–90) Nanjing, China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | Hu Yuecong, Hu Cheng-yen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | Publisher, artist, seal-carver | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Colour woodblock printing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable work | Ten Bamboo Studio Manual | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 胡正言 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 曰從 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 曰从 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hu Zhengyan (Chinese: 胡正言; c. 1584 – 1674) was a Chinese artist, printmaker and publisher. He worked in calligraphy, traditional Chinese painting, and seal-carving, but was primarily a publisher, producing academic texts as well as records of his own work.

Hu lived in Nanjing during the transition from the Ming dynasty to the Qing dynasty. A Ming loyalist, he was offered a position at the rump court of the Hongguang Emperor, but declined the post, and never held anything more than minor political office. He did, however, design the Hongguang Emperor's personal seal, and his loyalty to the dynasty was such that he largely retired from society after the emperor's capture and death in 1645. He owned and operated an academic publishing house called the Ten Bamboo Studio, in which he practised various multi-colour printing and embossing techniques, and he employed several members of his family in this enterprise. Hu's work at the Ten Bamboo Studio pioneered new techniques in colour printmaking, leading to delicate gradations of colour which were not previously achievable in this art form.

Hu is best known for his manual of painting entitled The Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting and Calligraphy, an artist's primer which remained in print for around 200 years. His studio also published seal catalogues, academic and medical texts, books on poetry, and decorative writing papers. Many of these were edited and prefaced by Hu and his brothers.

Biography[edit]

Hu was born in Xiuning County, Anhui Province in 1584 or early 1585.[1] Both his father and elder brother Zhengxin (正心, art name Wusuo, 無所) were physicians, and after he turned 30 he travelled with them while they practised medicine in the areas around Lu'an and Huoshan.[2] It is commonly stated that Zhengyan himself was also a doctor,[2] though the earliest sources attesting to this occur only in the second half of the 19th century.[1]

By 1619, Hu had moved to Nanjing[1] where he lived with his wife Wu.[3] Their home on Jilongshan (雞籠山, now also known as Beiji Ge), a hill located just within the northern city wall,[1] served as a meeting-house for like-minded artists. Hu named it the Ten Bamboo Studio (Shizhuzhai, 十竹齋), after the ten bamboo plants that grew in front of the property.[3][4] It functioned as the headquarters for his printing business, where he employed ten artisans including his two brothers Zhengxin and Zhengxing (正行, art name Zizhu, 子著) and his sons Qipu (其樸) and Qiyi (其毅, courtesy name 致果).[1]

During Hu's lifetime, the Ming dynasty, which had ruled China for over 250 years, was overthrown and replaced by China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing. Following the fall of the capital Beijing in 1644, remnants of the imperial family and a few ministers set up a Ming loyalist regime in Nanjing with Zhu Yousong on the throne as the Hongguang Emperor.[5] Hu, who was noted for his seal-carving and facility with seal script, created a seal for the new Emperor. The court offered him the position of Drafter for the Secretariat (zhongshu sheren, 中書舍人) as a reward, but he did not accept the role (although he did accord himself the title of zhongshu sheren in some of his subsequent personal seals).[1]

According to Wen Ruilin's Lost History of the South (Nanjiang Yishi, 南疆繹史), prior to the Qing invasion of Nanjing Hu studied at the National University there, and whilst a student was employed by the Ministry of Rites to record official proclamations; he produced the Imperial Promotion of Minor Learning (Qin Ban Xiaoxue, 御頒小學) and the Record of Displayed Loyalty (Biaozhong Ji, 表忠記) as part of this work. As a result, he was promoted to the Ministry of Personnel and gained admittance to the Hanlin Academy, but before he could take up this appointment, Beijing had fallen to the Manchu rebellion.[6] Since contemporaneous biographies (Wen's work was not published until 1830) make no mention of these events, it has been suggested that they were fabricated after Hu's death.[1]

Hu retired from public life and went into seclusion in 1646, after the end of the Ming dynasty.[7] Xiao Yuncong and Lü Liuliang recorded visiting him during his later years, in 1667 and 1673 respectively.[2] He died in poverty at the age of 90, sometime around late 1673 or early 1674.[1]

Seal-carving[edit]

Hu Zhengyan was a noted seal-carver, producing personal seals for numerous dignitaries. His style was rooted in the classical seal script of the Han dynasty, and he followed the Huizhou school of carving founded by his contemporary He Zhen. Hu's calligraphy, although balanced and with a clear compositional structure, is somewhat more angular and rigid than the classical models he followed. Huizhou seals attempt to impart an ancient, weathered impression, although unlike other Huizhou artists Hu did not make a regular practice of artificially aging his seals.[1]

Hu's work was known outside his local area. Zhou Lianggong, a poet who lived in Nanjing around the same time as Hu and was a noted art connoisseur, stated in his Biography of Seal-Carvers (Yinren Zhuan, 印人傳) that Hu "creates miniature stone carvings with ancient seal inscriptions for travellers to fight over and treasure",[8] implying that his carvings were popular with visitors and travellers passing through Nanjing.[1][9]

In 1644, Hu took it upon himself to create a new Imperial seal for the Hongguang Emperor, which he carved after a period of fasting and prayer. He presented his creation with an essay, the Great Exhortation of the Seal (Dabao Zhen, 大寶箴), in which he bemoaned the loss of the Chongzhen Emperor's seal and begged Heaven's favour in restoring it. Hu was concerned that his essay would be overlooked because he had not written it in the form of rhyming, equally-footed couplets (pianti, 駢體) used in the Imperial examinations, but his submission and the seal itself were nevertheless both accepted by the Southern Ming court.[7]

Ten Bamboo Studio[edit]

Despite his reputation as an artist and seal-carver, Hu was primarily a publisher. His publishing house, the Ten Bamboo Studio, produced reference works on calligraphy, poetry and art; medical textbooks; books on etymology and phonetics; and copies of, as well as commentaries on, the Confucian Classics. Unlike other publishers in the area, the Ten Bamboo Studio did not publish works of narrative fiction such as plays or novels.[10] This bias towards academia was likely a consequence of the studio's location: the mountain on which Hu took up residence was just to the north of the Nanjing Guozijian (National Academy), which provided a captive market for academic texts.[11] Between 1627 and 1644, the Ten Bamboo Studio produced over twenty printed books of this kind, aimed at a wealthy, literary audience.[12] The studio's earliest publications were medical textbooks, the first of which, Tested Prescriptions for Myriad Illnesses (Wanbing Yanfang, 萬病驗方) was published in 1631 and proved popular enough to be reissued ten years later. Hu's brother Zhengxin was a medical practitioner and appears to have been the author of these books.[1]

During the 1630s the Ten Bamboo Studio also produced political works extolling the rule of the Ming; these included the Imperial Ming Record of Loyalty (Huang Ming Biaozhong Ji, 皇明表忠紀), a biography of loyal Ming officials, and the Edicts of the Imperial Ming (Huang Ming Zhaozhi, 皇明詔制), a list of Imperial proclamations. After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, Hu renamed the studio the Hall Rooted in the Past (Digutang, 迪古堂) as a sign of his affiliation with the previous dynasty, although the Ten Bamboo imprint continued to be used. Despite Hu's withdrawal from society after 1646, the studio continued to publish well into the Qing dynasty, for the most part focussing on seal impression catalogues showcasing Hu's carving work.[1]

The Ming dynasty had seen considerable advancement in the process of colour printing in China.[13][14] At his studio, Hu Zhengyan experimented with various forms of woodblock printing, creating processes for producing multi-coloured prints and embossed printed designs.[15] As a result, he was able to produce some of China's first printed publications in colour, using a block printing technique known as "assorted block printing" (douban yinshua, 饾板印刷).[16][17][18] This system made use of multiple blocks, each carved with a different part of the final image and each bearing a different colour.[19] It was a lengthy, painstaking process, requiring thirty to fifty engraved printing blocks and up to seventy inkings and impressions to create a single image.[3] Hu also employed a related form of multiple-block printing called "set-block printing" (taoban yinshua, 套板印刷), which had existed since the Yuan period some 200 years earlier but had only recently come into fashion again.[4][20][21] He refined these block printing techniques by developing a process for wiping some of the ink off the blocks before printing; this enabled him to achieve gradation and modulation of shades which were not previously possible.[22]

In some images, Hu employed a blind embossing technique (known as "embossed designs" (gonghua, 拱花) or "embossed blocks" (gongban, 拱板), using an uninked, imprinted block to stamp designs onto paper. He used this to create white relief effects for clouds and for highlights on water or plants.[3] This was a relatively new process, having been invented by Hu's contemporary Wu Faxiang, who was also a Nanjing-based publisher. Wu had used this technique for the first time in his book Wisteria Studio Letter Paper (Luoxuan Biangu Jianpu, 蘿軒變古箋譜), published in 1626.[23][24] Both Hu and Wu used embossing to create decorative writing papers, the sale of which provided a sideline income for the Ten Bamboo Studio.[25]

Major works[edit]

Hu's most notable work is the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting and Calligraphy (Shizhuzhai Shuhuapu, 十竹齋書畫譜), an anthology of around 320 prints by around thirty different artists (including Hu himself), published in 1633. It consists of eight sections, covering calligraphy, bamboo, flowers, rocks, birds and animals, plum blossoms, orchids and fruit. Some of these sections had been released previously as single volumes.[24] As well as a collection of artworks, it was also intended as an artistic primer, with instructions on correct brush position and technique and several pictures designed for beginners to copy. Although these instructions only appear in the sections on orchids and bamboo, the book still remains the first example of a categorical and analytical approach to Chinese painting.[1][26] In this book, Hu used his multiple-block printing methods to obtain gradations of colour in the images, rather than obvious outlines or overlaps.[21] The manual is bound in the "butterfly binding" (hudie zhuang, 蝴蝶裝) style, whereby whole-folio illustrations are folded so that each occupies a double-page spread. This binding style allows the reader to lay the book flat in order to look at a particular image.[4] Cambridge University Library released a complete digital scan of the manual, including all writings and illustrations in August, 2015.[27] Said Charles Aylmer, Head of the Cambridge University Chinese Department, "The binding is so fragile, and the manual so delicate, that until it was digitized, we have never been able to let anyone look through it or study it – despite its undoubted importance to scholars."[28]

This volume went on to influence colour printing across China, where it paved the way for the later but better-known Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (Jieziyuan Huazhuan 芥子園畫傳), and also in Japan, where it was reprinted and foreshadowed the development in ukiyo-e of the colour woodblock printing process known as nishiki-e (錦絵).[29][30][31] The popularity of the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual was such that print runs continued to be produced all the way through to the late Qing dynasty.[1]

Hu also produced the work Ten Bamboo Studio Letter Paper (Shizhuzhai Jianpu, 十竹齋箋譜), a collection of paper samples, which made use of the gonghua stamped embossing technique to make the illustrations stand out in relief.[4][16][32][33] Whilst primarily a catalogue of decorative writing papers, it also contained paintings of rocks, people, ritual vessels and other subjects.[24] The book was bound in the "wrapped back" (baobei zhuang, 包背裝) style, in which the folio pages are folded, stacked, and sewn along the open edges.[9] Originally published in 1644, it was reissued in four volumes between 1934 and 1941 by Zheng Zhenduo and Lu Xun, and revised and republished again in 1952.[34]

Other publications[edit]

Other works produced by Hu's studio included a reprint of Zhou Boqi's manual of seal-script calligraphy, The Six Styles of Calligraphy, Correct and Erroneous (Liushu Zheng'e, 六書正譌) and the related Necessary Investigations into Calligraphy (Shufa Bi Ji, 書法必稽), which discussed common errors in the formation of characters. With his brother Zhengxin, Hu edited a new introductory edition of the Confucian classics, entitled The Standardised Text of the Four Books, Identified and Corrected (Sishu Dingben Bianzheng, 四書定本辨正) (1640), giving the correct formation and pronunciation of the text. A similar approach was taken with the Essentials of the Thousand Character Classic in Six Scripts (Qianwen Liushu Tongyao, 千文六書統要) (1663), which Hu compiled with the aid of his calligraphy teacher, Li Deng. It was published after Li's death, partly in homage to him.[1]

The three Hu brothers worked together to collate a student primer on poetry by their contemporary Ye Tingxiu, which was called simply the Discussion of Poetry (Shi Tan, 詩譚) (1635). Other works on poetry from the studio included Helpful Principles to the Subtle Workings of Selected Tang Poems (Leixuan Tang Shi Zhudao Weiji, 類選唐詩助道微機), which was a compilation of several works on poetry and included colophons by Hu Zhengyan himself.[1]

Among the studio's more obscure publications was a text on Chinese dominoes entitled Paitong Fuyu (牌統浮玉), written under a pseudonym but with a preface by Hu Zhengyan.[1]

Gallery[edit]

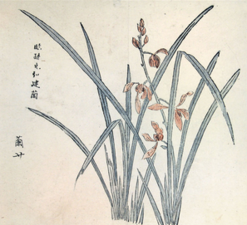

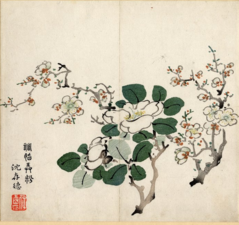

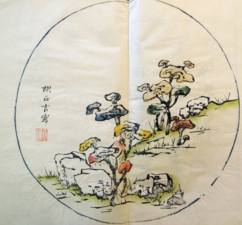

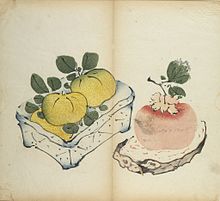

- Images from the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting and Calligraphy

-

Orchid

-

Chrysanthemum

-

Apple Blossom

-

Cherry Blossom and Bamboo

-

Bird on a Flowering Branch

-

Three Oranges on a Knotted Stand

-

Bird on a Branch

-

Toadstools

-

Chestnuts

-

Tangerines

-

Plum Blossoms and Pine

-

Diagram of correct brush position

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Wright, Suzanne E. (2008). "Hu Zhengyan: Fashioning Biography". Ars Orientalis. 35. The Smithsonian Institution: 129–154. JSTOR 25481910.

- ^ a b c Sun Shaobin. "十竹斋" [Ten Bamboo Studio]. ZhuoKeArts.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Lu, Yongxiang (10 October 2014). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Springer. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-3-662-44166-4.

- ^ a b c d Rawson, J., ed. (2007). The British Museum book of Chinese Art. London: The British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2446-9. Archived from the original on 2015-10-20.

- ^ Twitchett, Denis Crispin; Fairbank, John King (1988). The Cambridge History of China: The Ming dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 642. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ 温睿臨 (1971). 南疆逸史 (in Chinese). 崇文書店. pp. 306–307. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b 杜濬 (1894). 變雅堂遺集 (in Chinese). 上海古籍出版社. pp. 18–20. ISBN 9787532524600. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ 印人传 (in Chinese). 海南出版社. 2000. ISBN 978-7-80645-663-7. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ a b Wright, Suzanne E. (2003). ""Luoxuan biangu jianpu" and "Shizhuzhai jianpu": Two Late-Ming Catalogues of Letter Paper Designs". Artibus Asiae. 63 (1): 69–115. JSTOR 3249694.

- ^ Brokaw, Cynthia J.; Chow, Kai-Wing (2005). Printing and book culture in late Imperial China. University of California Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-520-23126-9. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ 馬孟晶 (1993). 晚明金陵"十竹齋書畫譜""十竹齋箋譜"硏究 (in Chinese). National Taiwan University Dept. of Art History. pp. 29–30. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Chow, Kai-Wing (2004). Publishing, culture, and power in early modern China. Stanford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8047-3368-7. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Wu, Kuang-Ch'ing (1943). "Ming Printing and Printers". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 7 (3). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 203–210. doi:10.2307/2718015. JSTOR 2718015.

- ^ "The Art of Chinese Traditional Woodblock Printing" (PDF). Hong Kong Heritage Museum. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Fan, Dainian; Cohen, R.S. (30 September 1996). Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Springer. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-7923-3463-7. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Hu Zhengyan". China Culture. China Daily. 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Guo, Hua (1621). "Selected Anecdotes about Su Shi and Mi Fu". Chinese Rare Book Collection. World Digital Library. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Hegel, Robert E. (1998). Reading Illustrated Fiction in the Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8047-3002-0. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Applying colors". Gems of the Rare Books from the National Palace Museum's Collections. National Palace Museum. 2009-09-14. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Ding, Naifei (18 July 2002). Obscene Things: Sexual Politics in Jin Ping Mei. Duke University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8223-2916-9.

- ^ a b Bray, Francesca; Dorofeeva-Lichtmann, Vera; Métailié, Georges (1 January 2007). Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft. BRILL. p. 464. ISBN 978-90-04-16063-7.

- ^ Ebrey, Thomas. "The Editions, Superstates and States of the Ten Bamboo Studio Collection of Calligraphy and Painting" (PDF). East Asian Library and Gest Collection. Princeton University. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Eliot, Simon; Rose, Jonathan (24 August 2011). A Companion to the History of the Book. John Wiley & Sons. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4443-5658-8.

- ^ a b c Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (11 July 1985). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5.

- ^ Wright, Suzanne (28 April 2015). "Chinese Decorated Letter Papers". In Richter, Antje (ed.). A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture. BRILL. p. 116. ISBN 978-90-04-29212-3.

- ^ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (February 1975). "Book Review: Chinese Colour Prints from the Ten Bamboo Studio". Journal of Asian Studies. 34 (2): 514. doi:10.2307/2052768. JSTOR 2052768.

- ^ "Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (FH.910.83-98)". University of Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "One of World's Oldest Books Printed in Multi-Color Now Opened & Digitized for the First Time". Open Culture. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Culture of China. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-61530-140-9. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Michener, James Albert (1954). The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Paine, Robert T. Jr. (December 1950). "The Ten Bamboo Studio". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 48 (274): 72–79. JSTOR 4171078.

- ^ The East Asian Library Journal. Gest Library of Princeton University. 1998. p. 96. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ van Gulik, Robert H. (1974). 中國古代房内考: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill Archive. p. 322. ISBN 978-90-04-03917-9. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "荣宝斋与鲁迅、郑振铎: 叁" [Rong Bao Zhai and Lu Xun, Zheng Zhenduo: Part 3] (in Chinese). RBZarts.COM. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

External links[edit]

- Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (Ten Bamboo Studio collection of calligraphy and painting), fully digitised 1633 edition in Cambridge Digital Library