Trichuris trichiura

| Whipworm(s) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Enoplea |

| Order: | Trichocephalida |

| Family: | Trichuridae |

| Genus: | Trichuris |

| Species: | T. trichiura

|

| Binomial name | |

| Trichuris trichiura (Linnaeus, 1771)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Ascaris trichiura Linnaeus, 1771 | |

Trichuris trichiura, Trichocephalus trichiuris or whipworm, is a parasitic roundworm (a type of helminth) that causes trichuriasis (a type of helminthiasis which is one of the neglected tropical diseases) when it infects a human large intestine. It is commonly known as the whipworm which refers to the shape of the worm; it looks like a whip with wider "handles" at the posterior end.[2] The helminth is also known to cause rectal prolapse.

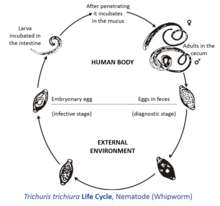

Life cycle

[edit]

The female T. trichiura produces 2,000–10,000 single-celled eggs per day.[3] Eggs are deposited from human feces to soil where, after two to three weeks, they become embryonated and enter the "infective" stage. These embryonated infective eggs are ingested by hand-mouth or through fomites and hatch in the human small intestine, exploiting the intestinal microflora as a stimulus to hatching.[4] This is the location of growth and molting. The infective larvae penetrate the villi and continue to develop in the small intestine. The young worms move to the caecum and penetrate the mucosa, and there they complete development as adult worms in the large intestine. The life cycle from the time of ingestion of eggs to the development of mature worms takes approximately three months. During this time, there may be limited signs of infection in stool samples, due to a lack of egg production and shedding. The female T. trichiura begin to lay eggs after three months of maturity. Worms commonly live for about one year,[5] during which time females can lay up to 20,000 eggs per day.

Recent studies using genome-wide scanning revealed that two quantitative trait loci on chromosome 9 and chromosome 18 may be responsible for a genetic predisposition or susceptibility to infection of T. trichiura by some individuals.[6]

Morphology

[edit]

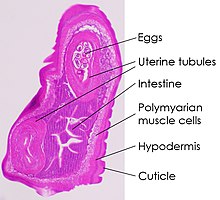

Trichuris trichiura has a narrow anterior esophageal end and shorter and thicker posterior end. These pinkish-white worms are threaded through the mucosa. They attach to the host through their slender anterior end and feed on tissue secretions instead of blood. Females are larger than males; approximately 35–50 mm long compared to 30–45 mm.[7] The females have a bluntly round posterior end compared to their male counterparts with a coiled posterior end. Their characteristic eggs are barrel-shaped and brown, and have bipolar protuberances.

Infection

[edit]Trichuriasis, also known as whipworm infection, occurs through ingestion of whipworm eggs and is more common in warmer climates. Whipworm eggs are passed in the feces of infected persons, and if an infected person defecates outdoors or if untreated human feces is used as fertilizer, eggs are deposited on soil where they can mature into an infective stage.[5] Ingestion of these eggs "can happen when hands or fingers that have contaminated dirt on them are put in the mouth or by consuming vegetables or fruits that have not been carefully cooked, washed or peeled."[5] The eggs hatch in the small intestine, then move into the wall of the small intestine and develop. On reaching adulthood, the thinner end (the anterior of the worm) burrows into the large intestine, the thicker (posterior) end projecting into the lumen, where it mates with nearby worms. The females can grow to 50 mm (2.0 in) long.[3]

Trichuris trichiura can cause the serious disease Trichuris dysentery syndrome (TDS), with chronic dysentery, anemia, rectal prolapse, and poor growth.[8] TDS is treated with anthelminthics as well as iron supplementation for anemia.[9]

Whipworm commonly infects patients also infected with Giardia, Entamoeba histolytica, Ascaris lumbricoides, and hookworms.[10]

Treatment

[edit]Trichuris trichiura can be treated with a single dose of albendazole.[11] In Kenya, half of a group of children, 98% of whom had Trichuris trichiura with or without infections by other soil-transmitted helminths, were given albendazole, while the other half of the children received placebos. It was found that the children who received the drug grew significantly better than the group of children who did not receive the treatment.[12] Another treatment that can be used is mebendazole, or flubendazole.[13] The medication interferes with the parasite’s nutrient intake, which eventually leads to death.

However, it has been shown that both albendazole and mebendazole have low cure rate for Trichuris thrichiura specifically, with treatments only achieving cure rates 30,7% for albendazole and 42,1% for mebendazole.[14]

Epidemiology

[edit]There is a worldwide distribution of Trichuris trichiura, with an estimated one billion human infections.[15][16][17][8] However, it is chiefly tropical, especially in Asia and, to a lesser degree, in Africa and South America. Within the United States, infection is rare overall but may be common in the rural Southeast, where 2.2 million people are thought to be infected. Poor hygiene is associated with trichuriasis as well as the consumption of shaded moist soil, or food that may have been fecally contaminated. Children are especially vulnerable to infection due to their high exposure risk. Eggs are infective about 2–3 weeks after they are deposited in the soil under proper conditions of warmth and moisture, hence its tropical distribution.

A closely related species, Trichuris suis, which typically infects pigs, is capable of infecting humans. This shows that the two species have very close evolutionary histories. However, morphology and developmental stages remain different, making them two separate species.[18]

WHO have since 2001 had a strategy for control of soil-transmitted helminths, including whipworms. This strategy entails treating at-risk individuals in the endemic areas. Risk groups for whipworm infections are children at preschool and school-aged children, people with specific high-risk jobs, women in reproductive and pregnant and breastfeeding women. The periodic treatment of the risk groups is done through either deworming campaigns or preventative chemotherapy.[19]

Treatment of inflammatory disorders

[edit]The hygiene hypothesis suggests that various immunological disorders that have been observed in humans only within the last 100 years, such as Crohn's disease, or that have become more common during that period as hygienic practices have become more widespread, may result from a lack of exposure to parasitic worms (helminths) during childhood. The use of Trichuris suis ova (TSO, or pig whipworm eggs) by Weinstock, et al., as a therapy for treating Crohn's disease[20][21][22] and to a lesser extent ulcerative colitis[23] are two examples that support this hypothesis. There is also anecdotal evidence that treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with TSO decreases the incidence of asthma,[24][self-published source?] allergy,[25] and other inflammatory disorders.[26] Some scientific evidence suggests that the course of multiple sclerosis may be very favorably altered by helminth infection;[27] TSO is being studied as a treatment for this disease.[28][29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Trichuris trichiura (Linnaeus, 1771)". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ EMedicine|article|788570|Trichuris Trichiura

- ^ a b Cross, John H. (1996). "Enteric Nematodes of Humans". In Baron, Samuel (ed.). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.

- ^ Hayes, K. S.; Bancroft, A. J.; Goldrick, M.; Portsmouth, C.; Roberts, I. S.; Grencis, R. K. (2010). "Exploitation of the Intestinal Microflora by the Parasitic Nematode Trichuris muris". Science. 328 (5984): 1391–4. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1391H. doi:10.1126/science.1187703. PMC 3428897. PMID 20538949.

- ^ a b c "CDC - Trichuriasis". 2019-04-25.

- ^ Williams-Blangero S, VandeBerg JL, Subedi J, Jha B, Dyer TD, Blangero J (2008). "Two Quantitative Trait Loci Influence Whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) Infection in a Nepalese Population". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (8): 1198–1203. doi:10.1086/533493. PMC 4122289. PMID 18462166.

- ^ "Trichuris trichiura definition - Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". Medterms.com. 2000-04-15. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ a b Stephenson, L.S.; Holland, C.V.; Cooper, E.S. (15 June 2001). "The public health significance of Trichuris trichiura" (PDF). Parasitology. 121 (S1): S73–S95. doi:10.1017/S0031182000006867. hdl:2262/40190. PMID 11386693. S2CID 7979360.

- ^ Stephenson, L.S.; Holland, C.V.; Cooper, E.S. (2000). "The public health significance of Trichuris trichiura". Parasitology. 121 (S1): S73–S95. doi:10.1017/S0031182000006867. hdl:2262/40190. PMID 11386693. S2CID 7979360.

- ^ "Otzi | Discovery & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- ^ Stephenson LS, Latham MC, Kurz KM, Kinoti SN, Brigham H (July 1989). "Treatment with a Single Dose of Albendazole Improves Growth of Kenyan Schoolchildren with Hookworm, Trichuris Trichiura, and Ascaris Lumbricoides Infections". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 41 (1): 78–87. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.78. PMID 2764230.

- ^ Stephenson LS, Latham MC, Adams EJ, Kinoti SN, Pertet A (1993). "Physical Fitness, Growth and Appetite of Kenyan School Boys with Hookworm, Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides Infections Are Improved Four Months After a Single Dose of Albendazole". The Journal of Nutrition. 123 (6): 1036–1046. doi:10.1093/jn/123.6.1036 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 8505663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Heyer, F.; Tourte-Schaeffer, Cl.; Ancelle, T.; Faurant, Cl.; Lapierre, J. (1 February 1982). "Le flubendazole : un progrès dans le traitement des helminthiases intestinales. A propos de 471 observations". Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses (in French). 12 (2): 57–61. doi:10.1016/S0399-077X(82)80047-4. ISSN 0399-077X.

- ^ Moser, Wendelin; Schindler, Christian; Keiser, Jennifer (2017-09-25). "Efficacy of recommended drugs against soil transmitted helminths: systematic review and network meta-analysis". BMJ. 358: j4307. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4307. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 5611648. PMID 28947636.

- ^ Crompton, DW (1999). "How much human helminthiasis is there in the world?". The Journal of Parasitology. 85 (3): 397–403. doi:10.2307/3285768. JSTOR 3285768. PMID 10386428.

- ^ de Silva, Nilanthi R; Brooker, Simon; Hotez, Peter J; Montresor, Antonio; Engels, Dirk; Savioli, Lorenzo (2003). "Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture". Trends in Parasitology. 19 (12): 547–51. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.002. PMID 14642761.

- ^ "Trichuris trichiura". WrongDiagnosis.com. 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Beer, RJ (January 1976). "The relationship between Trichuris trichiura (Linnaeus 1758) of man and Trichuris suis (Schrank 1788) of the pig". Research in Veterinary Science. 20 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1016/S0034-5288(18)33478-7. PMID 1257627.

- ^ "Soil-transmitted helminth infections". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ Hunter MM, McKay DM (2004). "Review article: helminths as therapeutic agents for inflammatory bowel disease". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 19 (2): 167–77. doi:10.1111/j.0269-2813.2004.01803.x. PMID 14723608. S2CID 73016367.

- ^ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF, Thompson R, Weinstock JV (2005). "Trichuris suis therapy in Crohn's disease". Gut. 54 (1): 87–90. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.041749. PMC 1774382. PMID 15591509.

- ^ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Qadir K, Urban JF, Thompson R, Weinstock JV (2003). "Trichuris suis seems to be safe and possibly effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98 (9): 2034–41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.457.8633. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07660.x. PMID 14499784. S2CID 2605979.

- ^ Buning, J; et al. (March 2008). "Helminths as governors of inflammatory bowel disease". Gut. 57 (8): 1182–1183. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.152355. PMID 18628388. S2CID 29967284.

in our patient Treg [regulatory T cells] activated by helminthosis [T. suis infestation] were most likely the key element protecting a host with latent ulcerative colitis against development of a severe protcocolitis. (1183)

- ^ "Helminthic Therapy: How to put your Asthma, Colitis, IBD, Crohn's or Multiple Sclerosis into remission with hookworm". Asthmahookworm.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-05. Retrieved 2009-05-19.[self-published source]

- ^ "Allergies: Trichuris suis Ova (TSO) Therapy to Treat Food Allergies". Allergizer.com. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Bager, Peter; Kapel, Christian; Roepstorff, Allan; Thamsborg, Stig; Arnved, John; Rønborg, Steen; Kristensen, Bjarne; Poulsen, Lars K.; Wohlfahrt, Jan (2011-08-02). "Symptoms after Ingestion of Pig Whipworm Trichuris suis Eggs in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Clinical Trial". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e22346. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622346B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022346. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3149054. PMID 21829616.

- ^ Correale J, Farez M (2007). "Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 61 (2): 97–108. doi:10.1002/ana.21067. PMID 17230481. S2CID 1033417.

- ^ "Asphelia Announces Initiation of an Independent TSO Trial for Multiple Sclerosis". redOrbit. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Klaver, Elsenoor J.; Kuijk, Loes M.; Laan, Lisa C.; Kringel, Helene; van Vliet, Sandra J.; Bouma, Gerd; Cummings, Richard D.; Kraal, Georg; van Die, Irma (2013). "Trichuris suis-induced modulation of human dendritic cell function is glycan-mediated". International Journal for Parasitology. 43 (3–4): 191–200. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.10.021. PMID 23220043.

Caroline Pomeroy, PhD July 9th, 2019.