Husayn ibn Hamdan

Husayn ibn Hamdan | |

|---|---|

| Died | October/November 918 Baghdad |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 895–915 |

| Relations | Hamdan ibn Hamdun (father), Abdallah ibn Hamdan and Sa'id ibn Hamdan (brother), Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla (nephews) |

Husayn ibn Hamdan ibn Hamdun ibn al-Harith al-Taghlibi (Arabic: حسين بن حمدان بن حمدون بن الحارث التغلبي) was an early member of the Hamdanid family, who distinguished himself as a general for the Abbasid Caliphate and played a major role in the Hamdanids' rise to power among the Arab tribes in the Jazira.

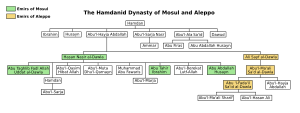

Husayn entered caliphal service in 895, and through his co-operation with the caliphal government, he established himself and his family as the leader of the Arabs and Kurds of the Jazira, leading his troops to successful campaigns against the Qarmatians, Dulafids and Tulunids over the next few years. As one of the most distinguished generals of the Abbasid Caliphate, he rose in power and influence until 908, when he was one of the leading conspirators in the abortive coup against Caliph al-Muqtadir. Although the coup failed and Husayn was forced to flee the capital, he soon secured a pardon and served as governor in Jibal, where he again distinguished himself in military operations in south-central Iran. In ca. 911, he was appointed governor in Mosul, where he remained until rising in revolt in 914/5, for reasons that are unclear. Defeated and captured in 916, he was imprisoned in Baghdad, where he was executed in 918. Through his influence, the family rose to high offices, beginning a long period during which Mosul and the entire Jazira were ruled by the Hamdanids. His nephews, Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla, went on to establish autonomous emirates in Mosul and Aleppo respectively.

Biography[edit]

Origin and early career[edit]

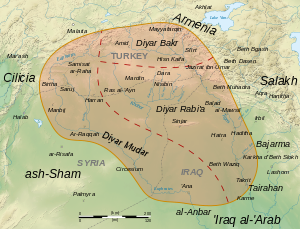

Husayn was a son of the Hamdanid family's patriarch, Hamdan ibn Hamdun. His family belonged to the Banu Taghlib tribe, established in the Jazira since before the Muslim conquests. In a pattern repeated across the Abbasid Caliphate, the Taghlibi leaders took advantage of the collapse of central caliphal authority during the decade-long Anarchy at Samarra (861–870) to assert increasing control over their particular area, centred on Mosul.[1] Hamdan established himself among the leading tribal leaders during this time, and led the resistance against caliphal attempts to restore direct control, even allying with the Kharijite rebels in the 880s. Finally, in 895 Caliph al-Mu'tadid launched a determined attack to recover the Jazira. Hamdan fled before the Caliph's advance and was captured after a long pursuit and thrown in prison.[2][3]

Husayn, however, who had been entrusted with the fortress of Ardumusht on the left bank of the Tigris, chose to surrender it instead, and offered his services to the Caliph. He managed to capture the Kharijite leader Harun al-Shari, thereby bringing an end to the Kharijite revolt in the Jazira. In exchange he secured not only a pardon for his father, but also the lifting of a tribute that the Taghlib had been forced to pay, and the right to form a regiment of 500 Taghlibi cavalry at government expense.[4][5] This was a major success, laying the groundwork for his own and his family's ascent to power. In the words of the Islamic scholar Hugh N. Kennedy,

to the caliph he offered a group of experienced warriors under his own skilled and loyal leadership; to the Taghlib, and other people in the Jazira, he offered the prospect of salaries and booty; and to his own family military command and the opportunity of acquiring wealth in government services. It was in fact not as an independent tribal leader, but rather as an intermediary between government and the Arabs and Kurds of the Jazira that al-Husayn made the family fortune.[2]

In Abbasid service[edit]

Husayn led his Taghlibi regiment with distinction over the next few years. He fought against the Dulafid Bakr ibn Abd al-Aziz ibn Ahmad ibn Abi Dulaf in the Jibal in 896.[4] After 903 he played a decisive role in the campaigns of Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Katib against the Qarmatians of the Syrian desert, where his experienced cavalry was crucial in countering the highly mobile Qarmatians. In 903 he participated in Muhammad's major victory over the Qarmatian leader al-Husayn ibn Zikrawayh, better known by his laqab of "Sahib al-Shama", near Hama. The Qarmatian leaders fled to the desert, but were soon captured, and brought in triumph to Baghdad.[4][6] Husayn then participated as commander of the vanguard in Muhammad's 904–905 campaign that ended the Tulunid dynasty and restored Syria and Egypt to direct caliphal control. Muhammad ibn Sulayman reportedly offered him the governorship of Egypt, but Husayn refused, preferring to return to Baghdad with the enormous booty he had collected.[4][7]

On his return from Egypt, in 905–906, Husayn was sent against the Banu Kalb of Syria, who had risen in revolt at the instigation of the Qarmatians. Although he drove them into the desert, the Kalbis filled up the wells as they retreated, and he was unable to follow them. As a result, the rebels were able to reach the Lower Euphrates, where they defeated another Abbasid force at al-Qadisiyya and raided the hajj caravan of the Mecca pilgrims (late 906). In the end, the forces of the central government defeated the Qarmatians and drove them to flight. On their retreat back to Syria along the Euphrates, they were attacked and annihilated by Husayn in March/April 907.[4] Although these victories did not entirely remove the Qarmatian threat—the Qarmatians based in Bahrayn continued to remain active and raided lower Iraq—they signalled the near-eradication of the sect from Syria.[8] Husayn then subdued the remaining Kalbi rebels between the Euphrates and Aleppo, and in 907–908 confronted and drove back into Syria the Banu Tamim who had invaded the Jazira seeking pillage, defeating them near Khunasira.[4]

By 908, this distinguished service had established Husayn as "one of the leading generals" (Kennedy) in the Caliphate, and enabled him to advance his own brothers to positions of power: they received various offices, the most important of which was the award of the governorship of Mosul to Husayn's brother Abu'l-Hayja Abdallah in 905.[9] In December 908, Husayn became involved in a palace plot to depose the new Caliph, al-Muqtadir, in favour of the older Ibn al-Mu'tazz. Along with two others, on 17 December 908 he attacked and killed the vizier al-Abbas ibn al-Hasan al-Jarjara'i, who had endorsed al-Muqtadir's accession. The conspirators then sought to kill the young caliph as well, but the latter had barricaded himself in the Hasani Palace. Ibn al-Mu'tazz was proclaimed as caliph, and Husayn went to the palace to persuade al-Muqtadir to surrender. However, the unexpected resistance of the palace servants under the chamberlains Sawsan, Mu'nis al-Fahl and Mu'nis al-Khadim, and the plotters' indecision, doomed the coup. Al-Muqtadir prevailed, and Husayn fled from Baghdad to Mosul and to Balad.[4][9] He then spent some time wandering with his followers across the Jazira. The caliph sent Husayn's own brother, Abu'l-Hayja Abdallah, to pursue him, but Husayn managed to surprise and defeat him. This success encouraged him to contact the new vizier, Ali ibn al-Furat, through the mediation of his brother Ibrahim. Although he had been a leading figure in the conspiracy, and most of the other participants in the coup were executed or imprisoned, Husayn succeeded in receiving a pardon. He was not welcomed back to Baghdad, however, but appointed governor of Qumm and Kashan in the Jibal.[4][9]

As governor, he aided Mu'nis al-Khadim in his campaign against the Saffarid al-Layth ibn Ali in Sijistan and Fars, and later against the former Saffarid general and rebel Subkara and his lieutenant al-Qattal. The Abbasid forces under Mu'nis al-Khadim succeeded in suppressing the rebellion by 910/1, with al-Qattal being captured by Husayn in person, according to a celebratory poem by the later Hamdanid poet Abu Firas.[4]

Abu Firas further reports that Husayn was offered the governorship of Fars, but refused, and returned to Baghdad. Ibn al-Furat, who probably still mistrusted his intentions, promptly dispatched him to the governorship of the Diyar Rabi'a, the province encompassing the eastern Jazira, including Mosul.[4][9] From this post, Husayn led a raiding campaign against the Byzantine Empire in 913/4.[4] Soon after, however, an open rift developed between Husayn and the vizier Ali ibn Isa al-Jarrah. The reason is unclear, but revolved around the finances of Husayn's province. In 914/5 he rose in open rebellion, assembling a force of 30,000 Arabs and Kurds in the Jazira, a testament to his influence there. He managed to defeat a caliphal army sent against him, but when confronted by the redoubtable Mu'nis al-Khadim, recalled from Egypt, he was defeated and captured in February 916 while trying to flee north into Armenia.[4][9] He was brought to Baghdad, where he was publicly paraded across the city in ritual humiliation, riding a camel and wearing a cap of shame. He was put into prison, and executed in October/November 918 on the caliph's orders.[4][9]

The reason for Husayn's execution is unclear. The historian of the Hamdanid dynasty, Marius Canard, suggested that it may have been due to his involvement in a Shi'a-inspired conspiracy, possibly connected to the dismissal of Ibn al-Furat from his second vizierate during the same period, or with the rebellion of the autonomous governor of Adharbayjan, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj, whom al-Muqtadir may have suspected of ties with the imprisoned Husayn. As Canard writes, "in any case the caliph must have feared that if Husayn were released he would once again start a revolt, either through a desire for independence or as a Shi'i. In order to avoid attempts by those (probably numerous) who desired his release to secure it by force, the caliph preferred to take a measure which put a stop to all intrigue".[4]

Despite Husayn's rebellion and execution, the Hamdanid family continued to prosper: his brothers were soon released from captivity, and Abdallah rose to prominence by aligning himself with Mu'nis al-Khadim and sharing in the ups and downs of the court politics in Baghdad. It was Abdallah's two sons, however, al-Hasan and Ali, better known by their honorific titles Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla, who established the family as the ruling dynasty in the semi-independent emirates of Mosul (until 978) and Aleppo (until 1002) respectively.[10][11]

Character and assessment[edit]

According to Canard, Husayn "stands out more clearly than the supreme commander Mu'nis or any other military leaders" of the period for his ability and valour, as well as for his restive and ambitious spirit. He was also singled out in being of Arab descent, an unusual case among the Caliphate's senior leaders of the period. Canard assesses him as unusually open-minded, and attuned to the ideological turmoil and ferment in the Muslim world of his time, as indicated by his contact with the Sufi mystic al-Hallaj, who dedicated a work on politics to Husayn. Indeed, according to Canard, Husayn's espousal of Shi'ism, and his participation in the abortive coup of 908, can best be seen in light of a desire—typical of Shi'a sympathisers—for a renewal of the Caliphate and the establishment of an "ideal Muslim government", something which the corrupt and decadent Abbasids were no longer capable of.[4] Finally, although it fell to his brother to found the actual Hamdanid dynasty, it was Husayn who first gave his family a taste of power and glory, for which he was later celebrated in the poetry of Abu Firas.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 266.

- ^ Canard 1971a, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Canard 1971a, pp. 619–620.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 182, 266.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 184, 266–267, 286.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2004, p. 267.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 267–282.

- ^ Canard 1971b, pp. 126–131.

Bibliography[edit]

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥusayn b. Ḥamdān". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 619–620. OCLC 495469525.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- 9th-century births

- 918 deaths

- 9th-century people from the Abbasid Caliphate

- 10th-century people from the Abbasid Caliphate

- 10th-century executions by the Abbasid Caliphate

- Abbasid governors of Jibal

- Abbasid governors of Mosul

- Abbasid people of the Arab–Byzantine wars

- Executed military personnel

- Generals of the Abbasid Caliphate

- Hamdanid dynasty

- Iraqi Shia Muslims

- Rebels from the Abbasid Caliphate

- 9th-century Arab people

- 10th-century Arab people