Emperor

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with Europe and East Asia and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Imperial, royal, noble, gentry and chivalric ranks in Europe |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

The word emperor (from Latin: imperator, via Old French: empereor)[1] can mean the male ruler of an empire. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules in her own right and name (empress regnant or suo jure). Emperors are generally recognized to be of the highest monarchic honour and rank, surpassing kings. In Europe, the title of Emperor has been used since the Middle Ages, considered in those times equal or almost equal in dignity to that of Pope due to the latter's position as visible head of the Church and spiritual leader of the Catholic part of Western Europe. The emperor of Japan is the only currently reigning monarch whose title is translated into English as "Emperor".[2]

Both emperors and kings are monarchs or sovereigns, both emperor and empress are considered monarchical titles. In as much as there is a strict definition of emperor, it is that an emperor has no relations implying the superiority of any other ruler and typically rules over more than one nation. Therefore, a king might be obliged to pay tribute to another ruler,[3] or be restrained in his actions in some unequal fashion, but an emperor should in theory be completely free of such restraints. However, monarchs heading empires have not always used the title in all contexts—the British sovereign did not assume the title Empress of the British Empire even during the incorporation of India, though she was declared Empress of India.

In Western Europe, the title of Emperor was used exclusively by the Holy Roman Emperor, whose imperial authority was derived from the concept of translatio imperii, i.e., they claimed succession to the authority of the Roman emperors, thus linking themselves to Roman institutions and traditions as part of state ideology. Although initially ruling much of Central Europe and northern Italy, by the 19th century, the emperor exercised little power beyond the German-speaking states.

Although technically an elective title, by the late 16th century, the imperial title had in practice come to be inherited by the Habsburg Archdukes of Austria and, following the Thirty Years' War, their control over the states (outside the Habsburg monarchy, i.e. Austria, Bohemia and various territories outside the empire) had become nearly non-existent. However, Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned Emperor of the French in 1804 and was shortly followed by Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, who declared himself Emperor of Austria in the same year. The position of Holy Roman Emperor nonetheless continued until Francis II abdicated that position in 1806. In Eastern Europe, the monarchs of Russia also used translatio imperii to wield imperial authority as successors to the Eastern Roman Empire. Their status was officially recognized by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1514, although not officially used by the Russian monarchs until 1547. However, the Russian emperors are better known by their Russian-language title of Tsar even after Peter the Great adopted the title of Emperor of All Russia in 1721.

Historians have liberally used "emperor" and "empire" anachronistically and out of its Roman and European context to describe any large state from the past or the present. Some titles are considered equivalent to "emperor" or are translated as "emperor". Examples of that are Roman emperors' titles, King of Kings, Khalifa, Huangdi, Cakravartin, Great Khan, Aztec monarchs' title, Inca monarchs' title, etc.[4] Sometimes this reference has even extended to non-monarchically ruled states and their spheres of influence, such as the Athenian Empire of the late 5th century BC, the Angevin Empire of the Plantagenets and the Soviet and American "empires" of the Cold War era. However, such "empires" did not need to be headed by an "emperor". "Empire" became identified instead with vast territorial holdings rather than the title of its ruler by the mid-18th century.

For purposes of protocol, the size and scope of a kingdom or empire may determine precedence in international diplomatic relations, but currently, precedence among heads of state who are sovereigns—whether they be kings, queens, emperors, empresses, princes, princesses and presidents may be determined by the size and scope or time that each one has been continuously in office. Outside the European context, "emperor" was the translation given to holders of titles who were accorded the same precedence as European emperors in diplomatic terms. In reciprocity, these rulers might accredit equal titles in their native languages to their European peers. Through centuries of international convention, this has become the dominant rule to identifying an emperor in the modern era.

Roman Empire

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Classical Antiquity

[edit]

When Republican Rome turned into a de facto monarchy in the second half of the 1st century BC, at first there was no name for the title of the new type of monarch. Ancient Romans abhorred the name Rex ("king"), and it was critical to the political order to maintain the forms and pretenses of republican rule. Julius Caesar had been Dictator, an acknowledged and traditional office in Republican Rome. Caesar was not the first to hold it, but following his assassination the term was abhorred in Rome.[citation needed]

Augustus, considered the first Roman emperor, established his hegemony by collecting on himself offices, titles, and honours of Republican Rome that had traditionally been distributed to different people, concentrating what had been distributed power in one man. One of these offices was princeps senatus, ("first man of the Senate") and became changed into Augustus' chief honorific, princeps civitatis ("first citizen") from which the modern English word and title prince is descended. The first period of the Roman Empire, from 27 BC to AD 284, is called the principate for this reason. However, it was the informal descriptive of Imperator ("commander") that became the title increasingly favored by his successors. Previously bestowed on high officials and military commanders who had imperium, Augustus reserved it exclusively to himself as the ultimate holder of all imperium. (Imperium is Latin for the authority to command, one of a various types of authority delineated in Roman political thought.)

Beginning with Augustus, Imperator appeared in the title of all Roman monarchs through the extinction of the Empire in 1453. After the reign of Augustus' immediate successor Tiberius, being proclaimed imperator was transformed into the act of accession to the head of state. Other honorifics used by the Roman emperors have also come to be synonyms for Emperor:

- Caesar Latin: [ˈkae̯sar] (as, for example, in Suetonius' Twelve Caesars). This tradition continued in many languages: in German it became "Kaiser"; in certain Slavic languages it became "Tsar"; in Hungarian it became "Császár", and several more variants. The name derived from Julius Caesar's cognomen "Caesar": this cognomen was adopted by all Roman emperors, exclusively by the ruling monarch after the Julio-Claudian dynasty had died out. In this tradition Julius Caesar is sometimes described as the first Caesar/emperor (following Suetonius). This is one of the most enduring titles: Caesar and its transliterations appeared in every year from the time of Caesar Augustus to the modern era.

- Augustus was the honorific first bestowed on Emperor Augustus: on his death it became an official title of his successor and all Roman emperors after him added it to their name. Although it had a high symbolic value, something like "elevated" or "sublime", it was generally not used to indicate the office of Emperor itself. Exceptions include the title of the Augustan History, a semi-historical collection of emperors' biographies of the 2nd and 3rd century. This title also proved very enduring: after the fall of the Roman Empire, the title would be incorporated into the style of the Holy Roman Emperor, a precedent set by Charlemagne, and its Greek translation Sebastos continued to be used in the Byzantine Empire until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, although it gradually lost its imperial exclusivity. Augustus had (by his last will) granted the feminine form of this honorific (Augusta) to his wife. Since there was no "title" of Empress(-consort) whatsoever, women of the reigning dynasty sought to be granted this honorific, as the highest attainable goal. Few were however granted the title, and it was certainly not a rule that all wives of reigning emperors would receive it.

- Imperator (as, for example, in Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia). In the Roman Republic Imperator meant "(military) commander". In the late Republic, as in the early years of the new monarchy, Imperator was a title granted to Roman generals by their troops and the Roman Senate after a great victory, roughly comparable to field marshal (head or commander of the entire army). For example, in AD 15 Germanicus was proclaimed Imperator during the reign of his adoptive father Tiberius. Soon thereafter "Imperator" became however a title reserved exclusively for the ruling monarch. This led to "Emperor" in English and, among other examples, "Empereur" in French and "Mbreti" in Albanian. The Latin feminine form Imperatrix only developed after "Imperator" had taken on the connotation of "Emperor".

- Autokrator (Αὐτοκράτωρ) or Basileus (βασιλεύς): although the Greeks used equivalents of "Caesar" (Καῖσαρ, Kaisar) and "Augustus" (in two forms: transliterated as Αὔγουστος, Augoustos or translated as Σεβαστός, Sebastos) these were rather used as part of the name of the emperor than as an indication of the office. Instead of developing a new name for the new type of monarchy, they used αὐτοκράτωρ (autokratōr, only partly overlapping with the modern understanding of "autocrat") or βασιλεύς (basileus, until then the usual name for "sovereign"). Autokratōr was essentially used as a translation of the Latin Imperator in Greek-speaking part of the Roman Empire, but also here there is only partial overlap between the meaning of the original Greek and Latin concepts. For the Greeks Autokratōr was not a military title, and was closer to the Latin dictator concept ("the one with unlimited power"), before it came to mean Emperor. Basileus appears not to have been used exclusively in the meaning of "emperor" (and specifically, the Roman/Byzantine emperor) before the 7th century, although it was a standard informal designation of the emperor in the Greek-speaking East. The title was later applied by the rulers of various Eastern Orthodox countries claiming to be the successors of Rome/Byzantium, such as Georgia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia.

After the turbulent Year of the Four Emperors in 69, the Flavian dynasty reigned for three decades. The succeeding Nervan-Antonian dynasty, ruling for most of the 2nd century, stabilised the empire. This epoch became known as the era of the Five Good Emperors, and was followed by the short-lived Severan dynasty.

During the Crisis of the 3rd century, barracks emperors succeeded one another at short intervals. Three short lived secessionist attempts had their own emperors: the Gallic Empire, the Britannic Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire though the latter used rex more regularly.

The Principate (27 BC – 284 AD) period was succeeded by what is known as the Dominate (284 AD – 527 AD), during which Emperor Diocletian tried to put the empire on a more formal footing. Diocletian sought to address the challenges of the Empire's now vast geography and the instability caused by the informality of succession by the creation of co-emperors and junior emperors. At one point, there were as many as five sharers of the imperium (see: Tetrarchy). In 325 AD Constantine I defeated his rivals and restored single emperor rule, but following his death the empire was divided among his sons. For a time the concept was of one empire ruled by multiple emperors with varying territory under their control, however following the death of Theodosius I the rule was divided between his two sons and increasingly became separate entities. The areas administered from Rome are referred to by historians the Western Roman Empire and those under the immediate authority of Constantinople called the Eastern Roman Empire or (after the Battle of Yarmouk in 636 AD) the Later Roman or Byzantine Empire. The subdivisions and co-emperor system were formally abolished by Emperor Zeno in 480 AD following the death of Julius Nepos last Western Emperor and the ascension of Odoacer as the de facto King of Italy in 476 AD.

Byzantine period

[edit]Before the 4th Crusade

[edit]

Historians generally refer to the continuing Roman Empire in the east as the Byzantine Empire after Byzantium, the original name of the town that Constantine I would elevate to the Imperial capital as New Rome in AD 330. (The city is more commonly called Constantinople and is today named Istanbul). Although the empire was again subdivided and a co-emperor sent to Italy at the end of the fourth century, the office became unitary again only 95 years later at the request of the Roman Senate and following the death of Julius Nepos, last Western Emperor. This change was a recognition of the reality that little remained of Imperial authority in the areas that had been the Western Empire, with even Rome and Italy itself now ruled by the essentially autonomous Odoacer.

These Later Roman "Byzantine" emperors completed the transition from the idea of the emperor as a semi-republican official to the emperor as an absolute monarch. Of particular note was the translation of the Latin Imperator into the Greek Basileus, after Emperor Heraclius changed the official language of the empire from Latin to Greek in AD 620. Basileus, a title which had long been used for Alexander the Great was already in common usage as the Greek word for the Roman emperor, but its definition and sense was "King" in Greek, essentially equivalent with the Latin Rex. Byzantine period emperors also used the Greek word "autokrator", meaning "one who rules himself", or "monarch", which was traditionally used by Greek writers to translate the Latin dictator. Essentially, the Greek language did not incorporate the nuances of the Ancient Roman concepts that distinguished imperium from other forms of political power.

In general usage, the Byzantine imperial title evolved from simply "emperor" (basileus) to "emperor of the Romans" (basileus tōn Rōmaiōn) in the 9th century, to "emperor and autocrat of the Romans" (basileus kai autokratōr tōn Rōmaiōn) in the 10th.[5] In fact, none of these (and other) additional epithets and titles had ever been completely discarded.

One important distinction between the post Constantine I (reigned AD 306–337) emperors and their pagan predecessors was cesaropapism, the assertion that the emperor (or other head of state) is also the head of the Church. Although this principle was held by all emperors after Constantine, it met with increasing resistance and ultimately rejection by bishops in the west after the effective end of Imperial power there. This concept became a key element of the meaning of "emperor" in the Byzantine and Orthodox east, but went out of favor in the west with the rise of Roman Catholicism.

The Byzantine Empire also produced three women who effectively governed the state: the Empress Irene and the Empresses Zoe and Theodora.

Latin emperors

[edit]In 1204 Constantinople fell to the Venetians and the Franks in the Fourth Crusade. Following the tragedy of the horrific sacking of the city, the conquerors declared a new "Empire of Romania", known to historians as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, installing Baldwin IX, Count of Flanders, as Emperor. However, Byzantine resistance to the new empire meant that it was in constant struggle to establish itself. Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos succeeded in recapturing Constantinople in 1261. The Principality of Achaea, a vassal state the empire had created in Morea (Greece) intermittently continued to recognize the authority of the crusader emperors for another half century. Pretenders to the title continued among the European nobility until circa 1383.

After the 4th Crusade

[edit]With Constantinople occupied, claimants to the imperial succession styled themselves as emperor in the chief centers of resistance: The Laskarid dynasty in the Empire of Nicaea, the Komnenid dynasty in the Empire of Trebizond and the Doukid dynasty in the Despotate of Epirus. In 1248, Epirus recognized the Nicaean emperors, who subsequently recaptured Constantinople in 1261. The Trapezuntine emperor formally submitted in Constantinople in 1281,[6] but frequently flouted convention by styling themselves emperor back in Trebizond thereafter.

Europe

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Byzantium's close cultural and political interaction with its Balkan neighbors Bulgaria and Serbia, and with Russia (Kievan Rus', then Muscovy) led to the adoption of Byzantine imperial traditions in all of these countries.

Holy Roman Empire

[edit]

The Emperor of the Romans' title was a reflection of the translatio imperii (transfer of rule) principle that regarded the Holy Roman emperors as the inheritors of the title of Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, despite the continued existence of the Roman Empire in the east, hence the problem of two emperors.

From the time of Otto the Great onward, much of the former Carolingian kingdom of Eastern Francia became the Holy Roman Empire. The prince-electors elected one of their peers as King of the Romans and King of Italy before being crowned by the Pope. The emperor could also pursue the election of his heir (usually a son) as King, who would then succeed him after his death. This junior king then bore the title of King of the Romans. Although technically already ruling, after the election he would be crowned as emperor by the pope. The last emperor to be crowned by the pope was Charles V; all emperors after him were technically emperors-elect, but were universally referred to as emperor.

The Holy Roman emperor was considered the first among those in power. He was also the first defender of Christianity. From 1452 to the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 (except in the years 1742 to 1745) only members of the House of Habsburg were Holy Roman emperors. Karl von Habsburg is currently the head of the House of Habsburg.[7][8][9]

Austrian Empire

[edit]

The first Austrian Emperor was the last Holy Roman Emperor, Franz II. In the face of aggressions by Napoleon, Francis feared for the future of the Holy Roman Empire. He wished to maintain his and his family's Imperial status in the event that the Holy Roman Empire should be dissolved, as it indeed was in 1806 when an Austrian-led army suffered a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz.[10] After which, the victorious Napoleon proceeded to dismantle the old Reich by severing a good portion from the empire and turning it into a separate Confederation of the Rhine. With the size of his imperial realm significantly reduced, Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor became Francis I, Emperor of Austria. The new imperial title may have sounded less prestigious than the old one, but Francis' dynasty continued to rule from Austria and a Habsburg monarch was still an emperor (Kaiser), and not just merely a king (König), in name. According to the historian Friedrich Heer, the Austrian Habsburg emperor remained an "auctoritas" of a special kind. He was "the grandson of the Caesars", he remained the patron of the Holy Church.[11]

The title lasted just a little over one century until 1918, but it was never clear what territory constituted the "Empire of Austria". When Francis took the title in 1804, the Habsburg lands as a whole were dubbed the Kaisertum Österreich. Kaisertum might literally be translated as "emperordom" (on analogy with "kingdom") or "emperor-ship"; the term denotes specifically "the territory ruled by an emperor", and is thus somewhat more general than Reich, which in 1804 carried connotations of universal rule. Austria proper (as opposed to the complex of Habsburg lands as a whole) had been part of the Archduchy of Austria since the 15th century, and most of the other territories of the Empire had their own institutions and territorial history. There were some attempts at centralization, especially during the reign of Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. These efforts were finalized in the early 19th century. When the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen (Hungary) were given self-government in 1867, the non-Hungarian portions were called the Empire of Austria. They were officially known as the "Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council (Reichsrat)". The title of Emperor of Austria and the associated Empire were both abolished at the end World War I in 1918, when German Austria became a republic and the other kingdoms and lands represented in the Imperial Council established their independence or adhesion to other states.

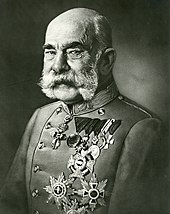

The Kaisers of the Austrian Empire (1804–1918) were Franz I (1804–1835), Ferdinand I (1835–1848), Franz Joseph I (1848–1916) and Karl I (1916–1918). The current head of the House of Habsburg is Karl von Habsburg.[12][13]

Bulgaria

[edit]In 913, Simeon I of Bulgaria was crowned Emperor (Tsar, originally more fully Tsesar, cěsar') of his own people by the Patriarch of Constantinople and Imperial regent Nicholas Mystikos outside the Byzantine capital.[14] In its final expanded form, under the Second Bulgarian Empire the title read "Emperor and Autocrat of all Bulgarians and Greeks" (Цар и самодържец на всички българи и гърци, Car i samodăržec na vsički bălgari i gărci in the modern vernacular).[15] The Roman component in the Bulgarian imperial title indicated both rule over Greek speakers and the derivation of the imperial tradition from the Romans, however this component was never recognised by the Byzantine court.

Byzantine recognition of Simeon's imperial title was revoked by the succeeding Byzantine government. The decade 914–924 was spent in destructive warfare between Byzantium and Bulgaria over this and other matters of conflict. The Bulgarian monarch, who had further irritated his Byzantine counterpart by claiming the title "Emperor of the Romans" (basileus tōn Rōmaiōn), was eventually recognized, as "Emperor of the Bulgarians" (basileus tōn Boulgarōn) by the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lakapenos in 924.[16] Byzantine recognition of the imperial dignity of the Bulgarian monarch and the patriarchal dignity of the Bulgarian patriarch was again confirmed at the conclusion of permanent peace and a Bulgarian-Byzantine dynastic marriage in 927. In the meantime, the Bulgarian imperial title may have been also tacitly confirmed by the pope, as claimed in later Bulgarian diplomatic correspondence.[17] The Bulgarian imperial title "tsar" was adopted by all Bulgarian monarchs up to the fall of Bulgaria under Ottoman rule. Despite the attempt of Pope Innocent III to limit the Bulgarian monarch to the title of King (Rex), Kaloyan of Bulgaria considered himself an Emperor (Imperator) and his successor Boril of Bulgaria was specifically accused of improperly using the imperial title by his neighbor, the Latin Emperor Henry of Flanders.[18] Nevertheless, the Bulgarian imperial title was recognized by its neighbors and trading partners, including Byzantium, Hungary, Serbia, Venice, Genoa, Dubrovnik. 14th-century Bulgarian literary compositions saw the Bulgarian capital (Tarnovo) as a successor of Rome and Constantinople.[19]

After Bulgaria obtained full independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1908, its monarch, who was previously styled Knyaz, Prince, took the traditional title of Tsar, this time translated as King. Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha is the former Tsar Simeon II of Bulgaria.[20]

France

[edit]The kings of the Ancien Régime and the July Monarchy used the title Empereur de France in diplomatic correspondence and treaties with the Ottoman emperor from at least 1673 onwards. The Ottomans insisted on this elevated style while refusing to recognize the Holy Roman emperors or the Russian tsars because of their rival claims of the Roman crown. In short, it was an indirect insult by the Ottomans to the HRE and the Russians. The French kings also used it for Morocco (1682) and Persia (1715).

First French Empire

[edit]

The painting by David commemorating the event is equally famous: the gothic cathedral restyled style Empire, supervised by the mother of the Emperor on the balcony (a fictional addition, while she had not been present at the ceremony), the pope positioned near the altar, Napoleon proceeds to crown his then wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais as Empress.

Napoleon Bonaparte, who was already First Consul of the French Republic (Premier Consul de la République française) for life, declared himself Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français) on 18 May 1804, thus creating the French Empire (Empire Français).[21]

Napoleon relinquished the title of Emperor of the French on 6 April and again on 11 April 1814. Napoleon's infant son, Napoleon II, was recognized by the Council of Peers, as Emperor from the moment of his father's abdication, and therefore reigned (as opposed to ruled) as Emperor for fifteen days, 22 June to 7 July 1815.

Elba

[edit]Since 3 May 1814, the Sovereign Principality of Elba was created as a miniature non-hereditary monarchy under the exiled French Emperor Napoleon I. According to the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1814), Napoleon I was allowed to enjoy the imperial title for life. The islands were not restyled an empire.

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon abandoned Elba for France, reviving the French Empire for a Hundred Days; the Allies declared an end to Napoleon's sovereignty over Elba on 25 March 1815, and on 31 March 1815 Elba was ceded to the restored Grand Duchy of Tuscany by the Congress of Vienna. After his final defeat, Napoleon was treated as a general by the British authorities during his second exile to Atlantic Isle of St. Helena. His title was a matter of dispute with the governor of St Helena, who insisted on addressing him as "General Bonaparte", despite the "historical reality that he had been an emperor" and therefore retained the title.[22][23][24]

Second French Empire

[edit]Napoleon I's nephew, Napoleon III, resurrected the title of emperor on 2 December 1852, after establishing the Second French Empire in a presidential coup, subsequently approved by a plebiscite.[25] His reign was marked by large scale public works, the development of social policy, and the extension of France's influence throughout the world. During his reign, he also set about creating the Second Mexican Empire (headed by his choice of Maximilian I of Mexico, a member of the House of Habsburg), to regain France's hold in the Americas and to achieve greatness for the 'Latin' race.[26] Napoleon III was deposed on 4 September 1870, after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. The Third Republic followed and after the death of his son Napoleon (IV), in 1879 during the Zulu War, the Bonapartist movement split, and the Third Republic was to last until 1940.

The role of head of the House of Bonaparte is claimed by Jean-Christophe Napoléon and Charles Napoléon.

Iberian Peninsula

[edit]Spain

[edit]The origin of the title Imperator totius Hispaniae (Latin for Emperor of All Spain[note 1]) is murky. It was associated with the Leonese monarchy perhaps as far back as Alfonso the Great (r. 866–910). The last two kings of its Astur-Leonese dynasty were called emperors in a contemporary source.[citation needed]

King Sancho III of Navarre conquered Leon in 1034 and began using it. His son, Ferdinand I of Castile also took the title in 1039. Ferdinand's son, Alfonso VI of León and Castile took the title in 1077. It then passed to his son-in-law, Alfonso I of Aragon in 1109. His stepson and Alfonso VI's grandson, Alfonso VII was the only one who actually had an imperial coronation in 1135.

The title was not exactly hereditary but self-proclaimed by those who had, wholly or partially, united the Christian northern part of the Iberian Peninsula, often at the expense of killing rival siblings. The popes and Holy Roman emperors protested at the usage of the imperial title as a usurpation of leadership in western Christendom. After Alfonso VII's death in 1157, the title was abandoned, and the kings who used it are not commonly mentioned as having been "emperors", in Spanish or other historiography.

After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the legitimate heir to the throne, Andreas Palaiologos, willed away his claim to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1503.[citation needed]

Portugal

[edit]

After the independence and proclamation of the Empire of Brazil from the Kingdom of Portugal by Prince Pedro, who became Emperor, in 1822, his father, King John VI of Portugal briefly held the honorific style of Titular Emperor of Brazil and the treatment of His Imperial and Royal Majesty under the 1825 Treaty of Rio de Janeiro, by which Portugal recognized the independence of Brazil. The style of Titular Emperor was a life title, and became extinct upon the holder's demise. John VI held the imperial title for a few months only, from the ratification of the Treaty in November 1825 until his death in March 1826. During those months, however, as John's imperial title was purely honorific while his son, Pedro I, remained the sole monarch of the Brazilian Empire. Duarte Pio is the current head of the House of Braganza.

Great Britain

[edit]In the late 3rd century, by the end of the epoch of the barracks emperors in Rome, there were two Britannic emperors, reigning for about a decade. After the end of Roman rule in Britain, the Imperator Cunedda forged the Kingdom of Gwynedd in northern Wales, but all his successors were titled kings and princes.

England

[edit]There was no consistent title for the king of England before 1066, and monarchs chose to style themselves as they pleased. Imperial titles were used inconsistently, beginning with Athelstan in 930 and ended with the Norman conquest of England. Empress Matilda (1102–1167) is the only English monarch commonly referred to as "emperor" or "empress", but she acquired her title through her marriage to Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor.

During the rule of Henry VIII the Statute in Restraint of Appeals declared that 'this realm of England is an Empire...governed by one Supreme Head and King having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial Crown of the same'. This was in the context of the divorce of Catherine of Aragon and the English Reformation, to emphasize that England had never accepted the quasi-imperial claims of the papacy. Hence England and, by extension its modern successor state, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, is according to English law an Empire ruled by a King endowed with the imperial dignity. However, this has not led to the creation of the title of Emperor in England, nor in Great Britain, nor in the United Kingdom.

United Kingdom

[edit]

In 1801, George III rejected the title of Emperor when offered. The only period when British monarchs held the title of Emperor in a dynastic succession started when the title Empress of India was created for Queen Victoria.[27] The government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, conferred the additional title upon her by an Act of Parliament, reputedly to assuage the monarch's irritation at being, as a mere Queen, notionally inferior to the emperors of Russia, Germany, and Austria. That included her own daughter (Princess Victoria, who was the wife of the reigning German Emperor). Hence, "Queen Victoria felt handicapped in the battle of protocol by not being an Empress herself".[28] The Indian Imperial designation was also formally justified as the expression of Britain succeeding the former Mughal Emperor as suzerain over hundreds of princely states. The Indian Independence Act 1947 provided for the abolition of the use of the title "Emperor of India" by the British monarch, but this was not executed by King George VI until a royal proclamation on 22 June 1948. Despite this, George VI continued as king of India until 1950 and as king of Pakistan until his death in 1952.

The last Empress of India was George VI's wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.

German Empire

[edit]

Under the guise of idealism giving way to realism, German nationalism rapidly shifted from its liberal and democratic character in 1848 to Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck's authoritarian Realpolitik. Bismarck wanted to unify the rival German states to achieve his aim of a conservative, Prussian-dominated Germany. Three wars led to military successes and helped to convince German people to do this: the Second war of Schleswig against Denmark in 1864, the Austro-Prussian War against Austria in 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War against the Second French Empire in 1870–71. During the Siege of Paris in 1871, the North German Confederation, supported by its allies from southern Germany, formed the German Empire with the proclamation of the Prussian king Wilhelm I as German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles,[29] to the humiliation of the French, who ceased to resist only days later.

After his death he was succeeded by his son Frederick III who was only emperor for 99 days. In the same year his son Wilhelm II became the third emperor within a year. He was the last German emperor. After the empire's defeat in World War I the empire, called the German Reich, had a president as head of state instead of an emperor. The use of the word Reich was abandoned following World War II.

Russia

[edit]

In 1472, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, Sophia Palaiologina, married Ivan III, grand prince of Moscow, who began championing the idea of Russia being the successor to the Byzantine Empire. This idea was represented more emphatically in the composition the monk Filofej addressed to their son Vasili III. In 1480, after ending Muscovy's dependence on its overlords of the Great Horde, Ivan III began the usage of the titles Tsar and Autocrat (samoderzhets). His insistence on recognition as such by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire since 1489 resulted in the granting of this recognition in 1514 by Emperor Maximilian I to Vasili III. His son Ivan IV emphatically crowned himself Tsar of Russia on 16 January 1547. The word "Tsar" derives from Latin Caesar, but this title was used in Russia as equivalent to "King"; the error occurred when medieval Russian clerics referred to the biblical Jewish kings with the same title that was used to designate Roman and Byzantine rulers — "Caesar".

On 31 October 1721, Peter I was proclaimed Emperor by the Governing Senate. The title used was Latin "Imperator", which is a westernizing form equivalent to the traditional Slavic title "Tsar". He based his claim partially upon a letter discovered in 1717 written in 1514 from Maximilian I to Vasili III, in which the Holy Roman Emperor used the term in referring to Vasili.

A formal address to the ruling Russian monarch adopted thereafter was 'Your Imperial Majesty'. The crown prince was addressed as 'Your Imperial Highness'.

The title has not been used in Russia since the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II on 15 March 1917.

The Russian Empire produced four reigning Empresses, all in the eighteenth century.

The role of head of the House of Romanov is claimed by Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna of Russia (Great-great-granddaughter of Alexander II of Russia), Prince Andrew Romanoff (great-great-grandson of Nicholas I of Russia), and Prince Karl Emich of Leiningen (Great-grandson of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia).

Serbia

[edit]

In 1345, the Serbian King Stefan Uroš IV Dušan proclaimed himself Emperor (Tsar) and was crowned as such at Skopje on Easter 1346 by the newly created Serbian Patriarch, and by the Patriarch of Bulgaria and the autocephalous Archbishop of Ohrid. His imperial title was recognized by Bulgaria and various other neighbors and trading partners but not by the Byzantine Empire. In its final standardized form, the Serbian imperial title read "Emperor of Serbs and Greeks" (цар Срба и Грка, car Srba i Grka in modern Serbian). It was only employed by two monarchs in Serbia, Stefan Uroš IV Dušan and his son Stefan Uroš V, becoming extinct after the latter's death in 1371. A half-brother of Dušan, Simeon Uroš, and then his son Jovan Uroš, claimed the same title, until the latter's abdication in 1373, while ruling as dynasts in Thessaly. The "Greek" component in the Serbian imperial title indicates both rule over Greek speakers and the derivation of the imperial tradition from the Romans.[30] A renegade Hungarian-Serb commander, Jovan Nenad, who claimed to be a descendant of Serbian and Byzantine rulers, styled himself Emperor.

The Americas

[edit]Pre-Columbian traditions

[edit]

The Aztec and Inca traditions are unrelated to one another. Both were conquered under the reign of King Charles I of Spain who was simultaneously emperor-elect of the Holy Roman Empire during the fall of the Aztecs and fully emperor during the fall of the Incas. Incidentally by being king of Spain, he was also Roman (Byzantine) emperor in pretence through Andreas Palaiologos. The translations of their titles were provided by the Spanish.

Aztec Empire

[edit]The only pre-Columbian North American rulers to be commonly called emperors were the Huey Tlatoani (es:Huey Tlatoani) of the Mexica city-states of Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan and Texcoco, which along with their allies and tributaries are popularly known as the Aztec Empire (1375–1521). Tlatoani is a generic Nahuatl word for "speaker"; however, most English translators use "king" for their translation, thus rendering huey tlatoani as great king or emperor.[31]

The Triple Alliance was an elected monarchy chosen by the elite. The emperors of Tenochtitlan and Texcoco were nominally equals, each receiving two-fifths of tribute from the vassal kingdoms, whereas the emperor of Tlacopan was a junior member and only received one-fifth of the tribute,[citation needed] due to the fact that Tlacopan was a newcomer to the alliance. Despite the nominal equality, Tenochtitlan eventually assumed a de facto dominant role in the Empire, to the point that even the emperors of Tlacopan and Texcoco would acknowledge Tenochtitlan's effective supremacy. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés executed Emperor Cuauhtémoc and installed puppet rulers who became vassals for Spain.

Inca Empire

[edit]The only pre-Columbian South American rulers to be commonly called emperors were the Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire (1438–1533). Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro, conquered the Inca for Spain, killed Emperor Atahualpa, and installed puppets as well. Atahualpa may actually be considered a usurper as he had achieved power by killing his half-brother and he did not perform the required coronation with the imperial crown mascaipacha by the Huillaq Uma (high priest).

Post-Columbian Americas

[edit]Brazil

[edit]

When Napoleon I ordered the invasion of Portugal in 1807 because it refused to join the Continental System, the Portuguese Braganzas moved their capital to Rio de Janeiro to avoid the fate of the Spanish Bourbons (Napoleon I arrested them and made his brother Joseph king). When the French general Jean-Andoche Junot arrived in Lisbon, the Portuguese fleet had already left with all the local elite.

In 1808, under a British naval escort, the fleet arrived in Brazil. Later, in 1815, the Portuguese Prince Regent (since 1816 King João VI) proclaimed the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, as a union of three kingdoms, lifting Brazil from its colonial status.

After the fall of Napoleon I and the Liberal revolution in Portugal, the Portuguese royal family returned to Europe (1821). Prince Pedro of Braganza (King João's older son) stayed in South America acting as regent of the local kingdom, but, two years later in 1822, he proclaimed himself Pedro I, first Emperor of Brazil. He did, however, recognize his father, João VI, as Titular Emperor of Brazil —a purely honorific title—until João VI's death in 1826.

The empire came to an end in 1889, with the overthrow of Emperor Pedro II (Pedro I's son and successor), when the Brazilian republic was proclaimed.

Today the headship of the Imperial House of Brazil is disputed between two branches of the House of Orléans-Braganza.

Haiti

[edit]Haiti was declared an empire by its ruler, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who made himself Jacques I, on 20 May 1805. He was assassinated the next year.[32] Haiti again became an empire from 1849 to 1859 under Faustin Soulouque.

Mexico

[edit]

In Mexico, the First Mexican Empire was the first of two empires created. After the declaration of independence on 15 September 1821, it was the intention of the Mexican parliament to establish a commonwealth whereby the king of Spain, Ferdinand VII, would also be Emperor of Mexico, but in which both countries were to be governed by separate laws and with their own legislative offices. Should the king refuse the position, the law provided for a member of the House of Bourbon to accede to the Mexican throne.

Ferdinand VII, however, did not recognize the independence and said that Spain would not allow any other European prince to take the throne of Mexico. By request of Parliament, the president of the regency Agustín de Iturbide was proclaimed emperor of Mexico on 12 July 1822 as Agustín I. Agustín de Iturbide was the general who helped secure Mexican independence from Spanish rule, but was overthrown by the Plan of Casa Mata.

In 1863, the invading French, under Napoleon III (see above), in alliance with Mexican conservatives and nobility, helped create the Second Mexican Empire, and invited Archduke Maximilian, of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, younger brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Josef I, to become emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. The childless Maximilian and his consort Empress Carlota of Mexico, daughter of Leopold I of Belgium, adopted Agustín's grandsons Agustin and Salvador as his heirs to bolster his claim to the throne of Mexico. Maximilian and Carlota made Chapultepec Castle their home, which has been the only palace in North America to house sovereigns.[citation needed] After the withdrawal of French protection in 1867, Maximilian was captured and executed by the liberal forces of Benito Juárez.[33]

This empire led to French influence in the Mexican culture and also immigration from France, Belgium, and Switzerland to Mexico. Maximilian's closest living agnatic relative is Karl von Habsburg, the head of the House of Habsburg.

Middle East

[edit]In Persia, from the time of Darius the Great, Persian rulers used the title "King of Kings" (Shahanshah in Persian) since they had dominion over peoples from the borders of India to the borders of Greece and Egypt.[34] Alexander the Great probably crowned himself shahanshah after conquering Persia,[35] bringing the phrase basileus ton basileon to Greek. It is also known that Tigranes the Great, king of Armenia, was named as the king of kings when he made his empire after defeating the Parthians. Georgian title "mephet'mephe" has the same meaning.

The last shahanshah (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) was ousted in 1979 following the Iranian Revolution. Shahanshah is usually translated as king of kings or simply king for ancient rulers of the Achaemenid, Arsacid, and Sassanid dynasties, and often shortened to shah for rulers since the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century. Iranian rulers were typically regarded in the West as emperors.

The title King of Kings takes various forms depending on the language, and was used not only in Iran but also in countries surrounding Iran.

- Šar Šarrāni,[36] the king of kings form of Šar, used in Assyria, Babylon, etc.

- Shahanshah,[36] the king of kings form of Shah, used in Iran, etc.

- Basileus Basileōn,[36] the king of kings form of Basileus, used in Macedonia, Byzantine, etc.

- Rajadhiraja,[36] the king of kings form of Raja, used in Champa, etc.

- Maharajadhiraja,[36] the king of kings form of Maharaja, used in Gupta, Nepal, etc.

- Sultan of Sultans, the king of kings form of Sultan, used in Ottoman, Delhi, etc.

- Malik al-Muluk,[37] the king of kings form of Malik, used in Palmyra, Buyid, etc.

- Mepe-Mepeta, the king of kings form of Mepe, used in Georgia.

- Nəgusä nägäst,[36] the king of kings form of Negus, used in Ethiopia.

Ottoman Empire

[edit]

Ottoman rulers held many titles and appellations denoting their Imperial status. These included: Sultan of Sultans, Padishah, and Hakan.

The full style of the Ottoman sultan once the empire's frontiers had stabilized became:[38][39]

Sultan (given name) Khan, Sovereign of The Sublime House of Osman, Sultan us-Selatin (Sultan of Sultans), Hakan (Khan of Khans), Commander of the faithful and Successor of the Prophet of the Lord of the Universe, Custodian of the Holy Cities of Mecca, Medina and Quds (Jerusalem), Padishah (Emperor) of The Three Cities of Istanbul (Constantinople), Edirne (Adrianople) and Bursa, and of the Cities of Châm (Damascus) and Cairo (Egypt), of all Azerbaijan, of the Maghreb, of Barkah, of Kairouan, of Alep, of the Arab and Persian Iraq, of Basra, of El Hasa strip, of Raqqa, of Mosul, of Parthia, of Diyâr-ı Bekr, of Cilicia, of the provinces of Erzurum, of Sivas, of Adana, of Karaman, of Van, of Barbaria, of Habech (Abyssinia), of Tunisia, of Tripoli, of Châm (Syria), of Cyprus, of Rhodes, of Crete, of the province of Morea (Peloponnese), of Bahr-i Sefid (Mediterranean Sea), of Bahr-i Siyah (Black Sea), of Anatolia, of Rumelia (the European part of the Empire), of Bagdad, of Kurdistan, of Greece, of Turkestan, of Tartary, of Circassia, of the two regions of Kabarda, of Gorjestan (Georgia), of the steppe of Kipchaks, of the whole country of the Tatars, of Kefa (Theodosia) and of all the neighbouring regions, of Bosnia, of the City and Fort of Belgrade, of the province of Sirbistan (Serbia), with all the castles and cities, of all Arnaut, of all Eflak (Wallachia) and Bogdania (Moldavia), as well as all the dependencies and borders, and many others countries and cities.

After the Ottoman capture of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman sultans began to style themselves Kaysar-i Rum (Ceaser of the Romans) as they asserted themselves to be the heirs to the Roman Empire by right of conquest. The title was of such importance to them that it led them to eliminate the various Byzantine successor states – and therefore rival claimants – over the next eight years. Though the term "emperor" was rarely used by Westerners of the Ottoman sultan, it was generally accepted by Westerners that he had imperial status.

Harun Osman is currently the head of the Ottoman dynasty.

Indian subcontinent

[edit]Samrajya and Chakravarti systems

[edit]In the Vedic period, there was a federal imperial system called the Samrajya system and Samrat (hi:सम्राट्) was the title of the emperor of that system.[40] Those monarchs, who could bring under subjection many kings like rajan and maharajan, claimed the title of Samrat.[41]

Chandragupta of the Maurya Empire is referred to as the first emperor of the mostly unified Indian subcontinent.[42] Various other monarchs such as Pravarasena I, the Vakataka, and Yashodharman, the Aulikara, used the title of Samrat.[43]

Another type of Indian imperialism was called the Chakravarti system.[40] The first references to a Chakravartin as a secular monarch appear in reference to Ashoka of the Maurya Empire.[44]

The Pallava, Chola, Pandya and Vijayanagar dynasties claimed Chakravartin status.[45][46] Kharavela assumed the title of Kalinga-chakravartin.[47]

Magadhan Empire

[edit]

From 322 to 185 BC the Indian subcontinent was dominated by the Maurya dynasty of Magadha, whose monarchs used the title of Chakravarti Samrat.

Delhi Sultanate

[edit]From 1206 to 1526 most of the Indian subcontinent was dominated by the Muslim Delhi Sultanate, whose monarchs used the title Sultan of Sultans.

Mughal Empire

[edit]

From the 14th century until the 19th century the Indian subcontinent was dominated by predominantly Muslim rulers like the Mughals, whose rulers used the title Shahenshah and Padishah (or Badshah) of Hindustan.

British Raj

[edit]When the British monarchs ruled over India, they adopted the additional title of Kaisar-i-Hind (transl. Emperor of India).

Regional emperors

[edit]Vakataka

[edit]The Vakataka ruler, Pravarasena I was titled Samrat after he established his overlordship over the Deccan.

Kalinga

[edit]The ruler of Kalinga, Kharavela of the Mahameghavahana dynasty, used the title Kalinga-Chakravartin.

Malwa

[edit]The ruler of Malava, Yashodharman Vishnuvardhana of the Aulikara dynasty, used the title Samrat after his territorial conquest of Hunnic territories.

Chola

[edit]The Imperial Chola monarchs used the title Chakravartigal.

Vijayanagara

[edit]From 1336 to 1646, South India was ruled by the Vijayanagara Empire, whose monarchs used the title of Chakravarti Raya of Karnata.

Africa

[edit]Ethiopia

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

From 1270 the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia used the title Nəgusä Nägäst, literally "King of Kings". The use of the king of kings style began a millennium earlier in this region, however, with the title being used by the kings of Aksum, beginning with Sembrouthes in the 3rd century.

Another title used by this dynasty was Itegue Zetopia. Itegue translates as Empress, and was used by the only reigning Empress, Zauditu, along with the official title Negiste Negest ("Queen of Kings").

In 1936, the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III claimed the title of Emperor of Ethiopia after Ethiopia was occupied by Italy during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. After the defeat of the Italians by the British and the Ethiopians in 1941, Haile Selassie was restored to the throne but Victor Emmanuel did not relinquish his claim until 1943, even though he had no standing to the title.[48]

The current head of the Solomonic dynasty is Zera Yacob Amha Selassie.

Central African Empire

[edit]In 1976, President Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Republic, proclaimed the country to be an autocratic Central African Empire, and made himself Emperor as Bokassa I. The expenses of his coronation ceremony actually bankrupted the country. He was overthrown three years later and the republic was restored.[49]

East Asia

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

皇帝 is the title of emperors in East Asia. An emperor is called Huángdì in Chinese, Hwangje in Korean, Hoàng đế in Vietnamese, and Kōtei in Japanese, but these are all just their respective pronunciations of the Chinese character 皇帝. But, the Japanese call only their emperors with the special title Tennō (天皇).

The rulers of China and (once Westerners became aware of the role) Japan were always accepted in the West as emperors, and referred to as such. The claims of other East Asian monarchies to the title may have been accepted for diplomatic purposes, but it was not necessarily used in more general contexts.

China

[edit]

The East Asian tradition is different from the Roman tradition, having arisen separately. What links them together is the use of the Chinese logographs 皇 (huáng) and 帝 (dì) which together or individually are imperial. Because of the cultural influence of China, China's neighbors adopted these titles or had their native titles conform in hanzi. Anyone who spoke to the emperor was to address the emperor as bìxià (陛下, lit. the "Bottom of the Steps"), corresponding to the Imperial Majesty"; shèngshàng (聖上, lit. Holy Highness); or wànsuì (万岁, lit. "You, of Ten Thousand Years").

In 221 BC, Ying Zheng, who was king of Qin at the time, proclaimed himself Shi Huangdi (始皇帝), which translates as "first emperor". Huangdi is composed of huang ("august one", 皇) and di ("sage-king", 帝), and referred to legendary/mythological sage-emperors living several millennia earlier, of which three were huang and five were di. Thus Ying Zheng became Qin Shi Huang, abolishing the system where the huang/di titles were reserved to dead and/or mythological rulers. Since then, the title "king" became a lower ranked title, and later divided into two grades. Although not as popular, the title 王 wang (king or prince) was still used by many monarchs and dynasties in China up to the Taipings in the 19th century. 王 is pronounced vương in Vietnamese, ō in Japanese, and wang in Korean.

The imperial title continued in China until the Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1912. The title was briefly revived from 12 December 1915 to 22 March 1916 by President Yuan Shikai and again in early July 1917 when General Zhang Xun attempted to restore last Qing emperor Puyi to the throne. Puyi retained the title and attributes of a foreign emperor, as a personal status, until 1924. After the Japanese occupied Manchuria in 1931, they proclaimed it to be the Empire of Manchukuo, and Puyi became emperor of Manchukuo. This empire ceased to exist when it was occupied by the Soviet Red Army in 1945.[50]

In general, an emperor would have one empress (Huanghou, 皇后) at one time, although posthumous entitlement to empress for a concubine was not uncommon. The earliest known usage of huanghou was in the Han dynasty. The emperor would generally select the empress from his concubines. In subsequent dynasties, when the distinction between wife and concubine became more accentuated, the crown prince would have chosen an empress-designate before his reign. Imperial China produced only one reigning empress, Wu Zetian, and she used the same Chinese title as an emperor (Huangdi, 皇帝). Wu Zetian then reigned for about 15 years (AD 690–705).

Under the tributary system of China, monarchs of Korea and Vietnam sometimes called themselves emperor in their country. They introduced themselves as king for China and other countries (Emperor at home, king abroad). In Japan, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu a shogun was granted title of King of Japan for trade by the Ming emperor. However, the Shogun was a subject of the Japanese emperor. It was contrary to rules of tributary system, but the Ming emperor connived it for the purpose of suppressing the Wokou.

Japan

[edit]

The earliest emperor recorded in Kojiki and Nihon Shoki is Emperor Jimmu, who is said to be a descendant of Amaterasu's grandson Ninigi who descended from Heaven (Tenson kōrin). If one believes what is written in Nihon Shoki, the emperors have an unbroken direct male lineage that goes back more than 2,600 years.[51]

In ancient Japan, the earliest titles for the sovereign were either ヤマト大王/大君 (yamato ōkimi, Grand King of Yamato), 倭王/倭国王 (waō/wakokuō, King of Wa, used externally), or 治天下大王 (amenoshita shiroshimesu ōkimi, Grand King who rules all under heaven, used internally).

In 607, Empress Suiko sent a diplomatic document to China, which she wrote "the emperor of the land of the rising sun (日出處天子) sends a document to the emperor of the land of the setting sun (日沒處天子)" and began to use the title emperor externally.[52] As early as the 7th century, the word 天皇 (which can be read either as sumera no mikoto, divine order, or as tennō, Heavenly Emperor, the latter being derived from a Tang Chinese term referring to the Pole star around which all other stars revolve) began to be used. The earliest use of this term is found on a wooden slat, or mokkan, unearthed in Asuka-mura, Nara Prefecture in 1998. The slat dated back to the reign of Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jitō.[53] The reading 'Tennō' has become the standard title for the Japanese sovereign up to the present age. The term 帝 (mikado, Emperor) is also found in literary sources.

In the Japanese language, the word tennō is restricted to Japan's own monarch; kōtei (皇帝) is usually used for foreign emperors. Historically, retired emperors often kept power over a child-emperor as de facto regent. For a long time, a shōgun (formally the imperial military dictator, but made hereditary) or an imperial regent wielded actual political power. In fact, through much of Japanese history, the emperor has been little more than a figurehead. The Meiji Restoration restored practical abilities and the political system under Emperor Meiji.[54] The last shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu resigned in 1868.

After World War II, all claims of divinity were dropped (see Ningen-sengen). The Diet acquired all prerogative powers of the Crown, reverting the latter to a ceremonial role.[55] By 1979, after the short-lived Central African Empire (1976–1979), Emperor Shōwa was the only monarch in the world with the title emperor.[failed verification]

As of the early 21st century, Japan's succession law prohibits a female from ascending the throne. With the birth of a daughter as the first child of the then-Crown Prince Naruhito, Japan considered abandoning that rule. However, shortly after the announcement that Princess Kiko was pregnant with her third child, the proposal to alter the Imperial Household Law was suspended by then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. On 3 January 2007, as the child turned out to be a son, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe announced that he would drop the proposal.[56]

Emperor Naruhito is the 126th monarch according to Japan's traditional order of succession. The second and third in line of succession are Fumihito, Prince Akishino and Prince Hisahito. Historically, Japan has had eight reigning empresses who used the genderless title Tennō, rather than the female consort title kōgō (皇后) or chūgū (中宮). There is ongoing discussion of the Japanese Imperial succession controversy. Although current Japanese law prohibits female succession, all Japanese emperors claim to trace their lineage to Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess of the Shintō religion. Thus, the emperor is thought to be the highest authority of the Shinto religion, and one of his duties is to perform Shinto rituals for the people of Japan.

Korea

[edit]

Some rulers of Goguryeo (37 BC–AD 668) used the title of Taewang (태왕; 太王), literally translated as "Greatest King". The title of Taewang was also used by some rulers of Silla (57 BC–AD 935), including Beopheung and Jinheung.

The rulers of Balhae (698–926) internally called themselves Seongwang (성왕; 聖王; lit. "Holy King").[57]

The rulers of Goryeo (918–1392) used the titles of emperor and Son of Heaven of the East of the Ocean (해동천자; 海東天子). Goryeo's imperial system ended in 1270 with capitulation to the Mongol Empire.[58]

In 1897, Gojong, the king of Joseon, proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire (1897–1910), becoming the emperor of Korea. He declared the era name of "Gwangmu" (광무; 光武), meaning "Bright and Martial". The Korean Empire lasted until 1910, when it was annexed by the Empire of Japan.

Mongolia

[edit]

The Book of Wei, a Chinese history book, records that the title Khagan and the title Huángdì are the same.[60] The title Khagan (khan of khans or grand khan) was held by Genghis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire in 1206; he also formally took the Chinese title huangdi, as "Genghis Emperor" (成吉思皇帝; Chéngjísī Huángdì ). Only the Khagans from Genghis Khan to the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368 are normally referred to as emperors in English.

Vietnam

[edit]

Đại Việt Kingdom (40–43, 544–602, 938–1407, 1427–1945) (The first ruler of Vietnam to take the title of Emperor (Hoàng Đế) was the founder of the Early Lý dynasty, Lý Nam Đế, in the year AD 544)

Ngô Quyền, the first ruler of Đại Việt as an independent state, used the title Vương (王, King). However, after the death of Ngô Quyền, the country immersed in a civil war known as Anarchy of the 12 Warlords that lasted for over 20 years. In the end, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh unified the country after defeating all the warlords and became the first ruler of Đại Việt to use the title Hoàng Đế (皇帝, Emperor) in 968. Succeeding rulers in Vietnam then continued to use this Emperor title until 1806 when this title was stopped being used for a century.[61]

Đinh Bộ Lĩnh was not the first to claim the title of Đế (帝, Emperor). Before him, Lý Bí and Mai Thúc Loan also claimed this title. However, their rules were short-lived.[citation needed]

The Vietnamese emperors also gave this title to their ancestors who were lords or influential figures in the previous dynasty, as did the Chinese emperors. This practice was one of the many indications that Vietnam considered itself an equal to China which remained intact up to the twentieth century.[62]

In 1802 the newly established Nguyễn dynasty requested canonization from the Chinese Jiaqing Emperor and received the title Quốc Vương (國王, King of a State) and the name of the country as Việt Nam (越南) instead Đại Việt (大越). To avoid unnecessary armed conflicts, the Vietnamese rulers accepted this in diplomatic relation and used the title Emperor only domestically. However, Vietnamese rulers never accepted the vassalage relationship with China and always refused to come to Chinese courts to pay homage to Chinese rulers (a sign of vassalage acceptance). China waged a number of wars against Vietnam throughout history, and after each failure, settled for the tributary relationship. The Yuan dynasty under Kublai Khan waged three wars against Vietnam to force it into a vassalage relationship but after successive failures, Kublai Khan's successor, Temür Khan, finally settled for a tributary relationship with Vietnam. Vietnam sent tributary missions to China once in three years (with some periods of disruptions) until the 19th century, Sino-French War France replaced China in control of northern Vietnam.[63]

The emperors of the last dynasty of Vietnam continued to hold this title until the French conquered Vietnam. The emperor, however, was then a puppet figure only and could easily be disposed of by the French for more pro-France figure. Japan took Vietnam from France and the Axis-occupied Vietnam was declared an empire by the Japanese in March 1945. The line of emperors came to an end with Bảo Đại, who was deposed after the war, although he later served as head of state of South Vietnam from 1949 to 1955.[64]

See also

[edit]- Auctoritas – Roman prestige; contrast with power, imperium

- Lists of emperors

- Tlatoani – Ruler of a Mesoamerican āltepētl (city-state)

- Emperor Norton – Self-proclaimed Emperor of the United States (1818–1880)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Before the emergence of the modern country of Spain (beginning with the union of Castile and Aragon in 1492), the Latin word Hispania, in any of the Iberian Romance languages, either in singular or plural forms (in English: Spain or Spains), was used to refer to the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, and not exclusively, as in modern usage, to the country of Spain, thus excluding Portugal.

- ^ Agostino never saw the Sultan, but probably did see and sketch the helmet in Venice.

References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "emperor". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Uyama, Takuei (23 October 2019). "天皇はなぜ「王(キング)」ではなく「皇帝(エンペラー)」なのか" [The Title of the Monarch of Japan: not the "King" but the "Emperor"] (in Japanese). Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Peng, Ying-chen. "The Forbidden City". Khan Academy.

- ^ Malinowski, Gościwit (2022). "Imperator-Huangdi: The Idea of the Highest Universal Divine Ruler in the West and China". In Balbo, Andrea; Ahn, Jaewon; Kim, Kihoon (eds.). Empire and Politics in the Eastern and Western Civilizations. De Gruyter. pp. 16–19. doi:10.1515/9783110731590-002. ISBN 978-3-11-073159-0.

- ^ George Ostrogorsky, "Avtokrator i samodržac", Glas Srpske kraljevske akadamije CLXIV, Drugi razdred 84 (1935), 95–187.

- ^ Nicol, Donald MacGillivray, The Last Centuries of Byzantium, second edition (Cambridge: University Press, 1993), p. 74.

- ^ Heer, Friedrich. Holy Roman Empire (2002); Lonnie Johnson "Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends" (2011), p. 81.

- ^ "The Holy Roman Empire".

- ^ "Heiliges Römisches Reich : Geschichte der staatlichen Emanzipation". 27 August 2006.

- ^ liamfoley63 (6 August 2020). "August 6, 1806. Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire". European Royal History. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedrich Heer "Der Kampf um die österreichische Identität" (1981), p. 259.

- ^ Lonnie Johnson "Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends" (2011), p. 118.

- ^ Anatol Murad "Franz Joseph I of Austria and his Empire." (1968) p. 1.

- ^ Mladjov 2015: 171–177.

- ^ Charters of Ivan Alexander and Ivan Shishman, in Petkov 2008: 500, 506–507.

- ^ Mladjov 2015: 177–178.

- ^ Mladjov 1999.

- ^ Prinzing 1973: 420–421.

- ^ Kaimakamova 2006.

- ^ "Bulgaria's Former King and PM Simeon II Celebrates his 80th Birthday".

- ^ "Napoleon and War in 1804–05". www.fsmitha.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Napoleon, Vincent Cronin, p419, HarperCollins, 1994.

- ^ Napoleon, Frank McLynn, p644, Pimlico 1998.

- ^ Le Mémorial de Sainte Hélène, Emmanuel De Las Cases, Tome III, page101, published by Jean De Bonnot, Libraire à l'enseigne du canon, 1969.

- ^ "The Second French Empire (1852–1870)". About History. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Appelbaum, Nancy P.; Macpherson, Anne S.; Rosemblatt, Karin Alejandra (2003). Race and nation in modern Latin America. UNC Press Books. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8078-5441-9.

- ^ liamfoley63 (12 November 2019). "History of Styles and Titles Part IV: Emperor of Britain". European Royal History. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Longford, Elizabeth (1972). Queen Victoria: Born to Succeed. p. 404. ISBN 9780515028683. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Treaty of Frankfurt am Main ends Franco-Prussian War". HISTORY. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Fine 1987: 309–310.

- ^ Lockhart (2001, p.238); Schroeder (2007, p. 3). See also the entry for "TLAHTOANI" Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine, in Wimmer (2006).

- ^ "Jean-Jacques Dessalines". Biography. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "Mexican Historical Figures: Maximilian I". WeExpats. 24 July 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "Darius I". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Nick Kampouris in The Astounding, Immortal Story of Alexander the Great https://greekreporter.com/2019/01/30/the-astounding-immortal-story-of-alexander-the-great/ 30 Jan 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Malinowski, Gościwit (2022). "Imperator-Huangdi: The Idea of the Highest Universal Divine Ruler in the West and China". In Balbo, Andrea; Ahn, Jaewon; Kim, Kihoon (eds.). Empire and Politics in the Eastern and Western Civilizations. De Gruyter. pp. 7–8. doi:10.1515/9783110731590-002. ISBN 978-3-11-073159-0.

- ^ Savant, Sarah Bowen (30 September 2013). The New Muslims of Post-Conquest Iran: Tradition, Memory, and Conversion. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-107-29231-4.

- ^ "TheOttomans.org – The Ottomans History". theottomans.org. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkish And Ottoman Nobility And Royalty | Nobility Titles – Genuine Titles Of Nobility For Sale". Nobility Titles. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mahajan V.D. Ancient India. S. Chand Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 978-93-5253-132-5.

- ^ Luniya, Bhanwarlal Nathuram (1978). Life and Culture in Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to 1000 A.D. Lakshmi Narain Agarwal. p. 130.

- ^ Chandragupta in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 482. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

Pravarasena I was the only Vakataka king with the imperial title samrat; the others had the relatively modest title maharaja.

- ^ Chakravartin in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Burton Stein (1980). Peasant state and society in medieval South India. Oxford University Press. p. 70.

- ^ Desikachari, T. (1991). South Indian Coins. Asian Educational Services. p. 165. ISBN 978-81-206-0155-0.

- ^ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The age of imperial unity. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 213.

- ^ Vadala, Alexander Attilio (1 January 2011). "Elite Distinction and Regime Change: The Ethiopian Case". Comparative Sociology. 10 (4): 636–653. doi:10.1163/156913311X590664. ISSN 1569-1330.

- ^ Lentz, Harris M (1 January 1994). Heads of states and governments: a worldwide encyclopedia of over 2,300 leaders, 1945 through 1992. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0899509266.

- ^ "Manchukuo | puppet state created by Japan in China [1932]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "JAPANESE EMPEROR AND IMPERIAL FAMILY | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Satoshi Yabuuchi, 時代背景から知る 仏像の秘密, The Nikkei, 10 October 2019.

- ^ Masataka Kondo, ご存知ですか 3月2日は飛鳥池遺跡で「天皇」木簡が出土したと発表された日です, 2 March 2018.

- ^ Henry Kissinger on China. 2011, p. 79.

- ^ Although the Emperor of Japan is classified as constitutional monarch among political scientists, the current constitution of Japan defines him only as 'a symbol of the nation' and no subsequent legislation states his status as the Head of state or equates the Crown synonymously with any government establishment.

- ^ "Japan Imperial Succession".

- ^ New Book of Tang, vol. 209

- ^ Em, Henry (2013). The Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea. Duke University Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0822353720. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (25 October 2016). Genghis Khan and the Quest for God: How the World's Greatest Conqueror Gave Us Religious Freedom. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7352-2116-1.

- ^ Book of Wei, vol. 103; "「丘豆伐」猶魏言駕馭開張也,「可汗」猶魏言皇帝也。"

- ^ Dutton, George (2016). "From civil war to uncivil peace: The Vietnamese army and the early Nguyễn state (1802–1841)". South East Asia Research. 24 (2): 167–184. doi:10.1177/0967828X16649042. ISSN 0967-828X. JSTOR 26596471. S2CID 148779423.

- ^ Tuyet Nhung Tran, Anthony J. S. Reid (2006), Việt Nam Borderless Histories, Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, p. 67, ISBN 978-0-299-21770-9

- ^ Hurst, Ryan (20 May 2009). "Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) •". Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Vietnam: A Television History; America's Mandarin (1954–1963); Interview with Ngo Dinh Luyen". openvault.wgbh.org. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Bryce, James, 1st Viscount (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VIII (9th ed.). pp. 179–180.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Fine, J. V. A. Jr., The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, Ann Arbor, 1987.

- Kaimakamova, M., "Turnovo – New Constantinople: The Third Rome in the Fourteench-Century Bulgarian Translation of Constantine Manasses' Synopsis Chronike," The Medieval Chronicle 4 (2006) 91–104. online

- Mladjov, I. S. R., "Between Byzantium and Rome: Bulgaria in the aftermath of the Photian Schism," Byzantine Studies/Études Byzantines 4 (n.s.) (1999) 173–181. online

- Mladjov, I. S. R., "The Crown and the Veil: Titles, Spiritual Kinship, and Diplomacy in Tenth-Century Bulgaro-Byzantine Relations," History Compass 13 (2015) 171–183. online

- Petkov, K., The Voices of Medieval Bulgaria, Seventh-Fifteenth Century, Leiden, 2008.

- Prinzing, G., "Der Brief Kaiser Heinrichs von Konstantinopel vom 13. Januar 1212," Byzantion 43 (1973) 395–431. online