Ardagh–Johnson Line

The examples and perspective in this article may not include all significant viewpoints. (October 2019) |

The Ardagh–Johnson Line is the northeastern boundary of Kashmir drawn by surveyor William Johnson and recommended by John Charles Ardagh as the official boundary of India. It abuts China's Xinjiang and Tibet autonomous regions.[1]

The Ardagh–Johnson Line is one of three boundary lines considered by the British Indian government, the other two being the Macartney–MacDonald Line and a line along the Karakoram range. The British preference among the three choices varied over time based on the perception of their strategic interests in India.[1] The Ardagh–Johnson Line represented the "forward school" that wanted to advance the boundary as forward as possible as a defence against the growing Russian empire.[2] Following the Chinese reluctance to acquiesce to the more conservative Macartney–MacDonald Line, the British eventually reverted to the forward line in the Aksai Chin area, which was then inherited by the independent Republic of India.[3]

Etymology

[edit]

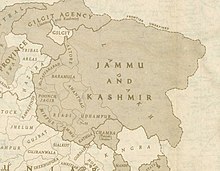

W. H. Johnson was the lead surveyor of Ladakh in the Kashmir Survey team instituted 1847–1865 by the Survey of India.[a] He surveyed the region now called Aksai Chin in 1865.[4][5] The results of the survey were published in a "Kashmir Atlas" in 1868.[6] The boundaries shown therein have been reproduced in practically all British and international maps of the British Raj till 1947. (See Maps 2–4.)

Major General John Charles Ardagh was the chief of the British military intelligence in London, who formally proposed to the British Indian government the alignment drawn by Johnson as the boundary of India in 1897.[1]

The term "Johnson boundary" was used by historian Alastair Lamb in his book The China–India Border (1964) and "Johnson line" by journalist Neville Maxwell. No names were used for the boundary lines in the northeast of Kashmir prior to these authors.[7] Scholar Steven Hoffman later used "Ardagh–Johnson Line" to refer to the line generally shown on British maps, which differs from the "Johnson line" in its northern boundary.[1]

Initial survey

[edit]

In May 1865, W. H. Johnson of the Survey of India was commissioned to undertake a survey of "beyond and to the north of the Chang Chenmo valley", as a part of the Kashmir Series.[8] Accordingly, he engaged in a hasty north–south traverse survey of the hitherto-unexplored Aksai Chin, following the main trade route — averaging about thirty miles per day.[9]

The resulting map was published in 1867.[10] Johnson noted that Khotan's border was at Brinjga, in the Kunlun Mountains, and the entire Karakash Valley was within the territory of Kashmir. The boundary of Kashmir that he drew, stretching from Sanju Pass to the eastern edge of Chang Chenmo Valley along the Kunlun mountains, is referred to as the "Johnson Line".[11]

In 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at St. Petersburg,[b] provided a map which coincided with the Ardagh–Johnson line in broad details. It showed the boundary of Xinjiang up to Raskam. In the east, it was similar to the Ardagh–Johnson line, placing Aksai Chin in Kashmir territory.[12]

Ardagh Proposal

[edit]

Since the late 1800s, local government officials were increasingly unhappy with accuracy of such traverse-maps and as a result, new surveys (along with boundary commissions) were frequently set up. However, extremely inhospitable geological conditions of Northeast Kashmir and difficulty in determining water-sheds across the Aksai Chin meant a continued lack of precision surveys covering this region.

In 1888, the Joint Commissioner of Ladakh requested India's Foreign Department to demarcate boundaries across northern and eastern Kashmir in a clear manner. After much back and forth, the department concluded that Johnson (and those who followed him) had an unconvincing view of the Indus watershed and their traverse-maps were too imprecise (and lacking in details) to serve the purpose of adjudicating territorial boundaries.

In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River.[13] At the time Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Ardagh–Johnson Line".

Aftermath

[edit]In 1911 the Xinhai Revolution resulted in power shifts in China, and by the end of World War I, the British officially used the Ardagh–Johnson Line.[14] From 1917 to 1933, the "Postal Atlas of China", published by the Government of China in Peking showed the boundary in Aksai Chin as per the Ardagh–Johnson line, which runs along the Kunlun Mountains.[15][16] The "Peking University Atlas", published in 1925, also put the Aksai Chin in India.[17]

Border of independent India

[edit]Upon independence in 1947, the government of India fixed its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin, in a manner that resembled the Ardagh–Johnson Line. India's basis for defining the border was “chiefly by long usage and custom.”.[18] Unlike the Johnson line, India did not claim the northern areas near Shahidulla and Khotan.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

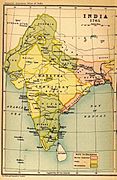

Map of India, 1765, implicitly showed the Aksai Chin region in India

-

Map of India, 1870, apparently incorporating the Johnson Line

-

Hung Ta-chen's map of the China border near Ladakh, 1893. Faithful reproduction by Dorothy Woodman. The boundary, marked with a thin dot-dashed line, matches the Johnson line for Aksai Chin.[19]

-

Postal Map of China published by the Government of China in 1917. The boundary in Aksai Chin is as per the Johnson line.

-

The map shows the Indian claim line in black dashes which is based on the Johnson line.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The organisation was called the "Great Trigonometrical Survey" in Johnson's time

- ^ Mehra, An "agreed" frontier 1992, p. 103: "Huang Tachin (also Hung Chun or Hung Tajen) was a Chinese diplomat accredited to Russia as well as Germany, Austria-Hungary and Holland in 1887-1890. During these years he rendered into Chinese a series of thirty-five maps, relating for the most part to the Sino-Russian borders."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 12.

- ^ Noorani, India–China Boundary Problem (2010), Chapter 4, "Two Schools on the Boundary".

- ^ Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 13.

- ^ Phillimore, Historical Records of the Survey of India, Volume 5 (1968), pp. 237–238.

- ^ Johnson, W. H. (1867), "Report on His Journey to Ilchí, the Capital of Khotan, in Chinese Tartary", The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 37: 1–47, doi:10.2307/1798517, JSTOR 1798517

- ^ Lamb, The China-India border (1964), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis (1990), p. 272, footnote 2 of Chapter 2: "The names now used for the several proposed borders of British days were coined by Alastair Lamb in his China-India Border book. Prior to that, it seems that the only Kashmir boundary given an official name was the Durand Line".

- ^ Lall 1989, pp. 3.

- ^ Gardner 2021, pp. 76, 235.

- ^ Gardner 2021, pp. 76.

- ^ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground 1963, p. 116.

- ^ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1969, pp. 73, 78: "Clarke added that a Chinese map drawn by Hung Ta-chen, Minister in St. Petersburg, confirmed the Johnson alignment showing West Aksai Chin as within British (Kashmir) territory."

- ^ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1969, pp. 101 and 360ff

- ^ Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011.

- ^ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1969.

- ^ Verma, Virendra Sahai (2006). "Sino-Indian Border Dispute At Aksai Chin – A Middle Path For Resolution" (PDF). Journal of Development Alternatives and Area Studies. 25 (3): 6–8. ISSN 1651-9728. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground 1963, p. 101.

- ^ Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India 2010, p. 235

- ^ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers 1969, pp. 73, 78.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Gardner, Kyle J. (2021). The Frontier Complex: Geopolitics and the Making of the India-China Border, 1846–1962. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-84059-0.

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Johnson, W. H. (1867), "Report on His Journey to Ilchí, the Capital of Khotan, in Chinese Tartary", The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 37: 1–47, doi:10.2307/1798517, JSTOR 1798517

- Lamb, Alastair (1964), The China-India border, Oxford University Press

- Lamb, Alastair (1973), The Sino-Indian Border in Ladakh (PDF), Australian National University Press

- Lall, John (1989), "Maps and Traditional Boundaries of Ladakh", China Report, 25 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1177/000944558902500101, S2CID 154641762

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-562758-9

- Noorani, A.G. (2010), India–China Boundary Problem 1846–1947: History and Diplomacy, Oxford University Press India, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198070689.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-908839-3

- Phillimore, R. H. (1960), "Survey of Kashmir and Jammu, 1855 to 1865", The Himalayan Journal, 22

- Phillimore, R. H. (1968), Historical Records of the Survey of India, Volume 5: 1844 to 1861, The Surveyor General of India – via archive.org

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969), Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger – via archive.org

![Hung Ta-chen's map of the China border near Ladakh, 1893. Faithful reproduction by Dorothy Woodman. The boundary, marked with a thin dot-dashed line, matches the Johnson line for Aksai Chin.[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Hung_Ta-Chen%27s_Map.jpg/147px-Hung_Ta-Chen%27s_Map.jpg)