Rani of Jhansi

| Lakshmibai Newalkar | |

|---|---|

| Maharani of Jhansi | |

Lakshmibai dressed as a sowar | |

| Queen consort of Jhansi | |

| Reign | 1843 – 21 November 1853 |

| Born | Manikarnika Tambe Varanasi |

| Died | June 18, 1858 Gwalior |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Damodar Rao Anand Rao (adopted) |

| Dynasty | Newalkar (by marriage) |

The Rani of Jhansi, also known as Rani Lakshmibai (ⓘ; born Manikarnika Tambe; 19 November 1828 — 18 June 1858) was the Maharani consort of the princely state of Jhansi in the Maratha Empire from 1843 to 1853 by marriage to Maharaja Gangadhar Rao Newalkar. She was one of the leading figures in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, who became a national hero and symbol of resistance to the British rule in India for Indian nationalists.

Born into a Marathi Karhade Brahmin family in Banares, Lakshmibai married the Maharaja of Jhansi, Gangadhar Rao, in 1842. When the Maharaja died in 1853, the British East India Company under Governor-General Lord Dalhousie refused to recognize the claim of his adopted heir and annexed Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse. The Rani was unwilling to cede control and joined the rebellion against the British in 1857. She led the successful defense of Jhansi against Company allies, but in early 1858 Jhansi fell to British forces under the command of Hugh Rose. The Rani managed to escape on horseback and joined the rebels in capturing Gwalior, where they proclaimed Nana Saheb as Peshwa of the revived Maratha Empire. She died in June 1858 after being mortally wounded during the British counterattack at Gwalior.

Biography

Little is known for certain about the Rani's life before 1857, because there was then no need to record details about an as-yet ordinary young girl. As a result, every biography of her life relies on a mixture of factual evidence and legendary tales, especially when concerning her childhood and adolescence.[1]

Early life and marriage

Moropant Tambe was a Maharashtrian Karhada Brahmin who served the Maratha noble Chimaji, whose brother Baji Rao II had been deposed as Maratha peshwa in 1817.[2] In the city of Varanasi, he and his wife Bhagirathi had a daughter, who they named Manakarnika, an epithet of the River Ganges; in childhood she was known by the diminutive Manu.[3] Her birth year is disputed: British sources tended towards the year 1827, whereas Indian sources generally preferred the year 1835. According to legend, the astrologers attending her birth foretold that she would combine the qualities of the three principle Hindu goddesses: Lakshmi, deity of wealth; Durga, deity of strength; and Saraswati, deity of knowledge.[4]

Both Manakarnika's mother Bhagirathi and her father's employer Chimaji died when she was a young child. Moropant moved to the court of Baji Rao at Bithur, who gave him a job and who became fond of Manakarnika, whom he nicknamed "Chhabili".[5] According to uncorroborated popular legend, her childhood playmates in Bithur included Nana Sahib and Tatya Tope, who would similarly become prominent in 1857. These stories relate that Manakarnika, deprived of a feminine influence by her mother's death, was allowed to play and learn with her male playmates: she was literate, skilled in horseriding, and—extremely unusually for a girl, if true—was given lessons in fencing, swordplay, and even firearms.[6]

It is presumed that Baji Rao brought Manakarnika to the attention of Gangadhar Rao, the old raja of Jhansi who had no children and greatly desired an heir. The ambitious Moropant accepted the unexpectedly prestigious marriage offer, and the couple wed, according to Indian sources, in May 1842. If the traditional chronology is correct, Manakarnika would have been seven years old, and the marriage would not have been consummated until she was fourteen.[7] Accorded the name Lakshmi, after the goddess, she was thereafter known as the Rani Lakshmibhai.[8] Both Indian and British sources portray Gangadhar Rao as an apolitical figure uninterested in rulership—thus increasing the scope for depicting the Rani's leadership abilities—but while British sources characterise him as debauched and imbecilic, Indian sources interpret these traits as evidence of his cultured nature.[9] According to popular legend, he turned blind eye to Rani Lakshmibhai's equipping and training of an armed all-female regiment, but if it existed, it was likely formed after Gangadhar Rao's death.[10]

God willing I still hope to recover and regain my health. I am not too old, so I may still father children. In case that happens, I will take the proper measures concerning my adopted son. But if I fail to live, please take my previous loyalty into account and show kindness to my son. Please acknowledge my widow as the mother of this boy during her lifetime. May the government approve of her as the queen and ruler of this kingdom as long as the boy is still under age. Please take care that no injustice is done to her.

In 1851, Lakshmibhai gave birth to a son amid much rejoicing, but he died at a few months old to the great grief of his parents.[12] Gangadhar Rao's health deteriorated and he died two years later on 21 November 1853. As was customary, he adopted a young boy on his deathbed—in this case, a five-year-old relative named Anand Rao, who was renamed Damodar Rao.[13] Two days before his death, Gangadhar Rao wrote a letter to East India Company officials, pleading them to recognise Damodar Rao as the new ruler and the Rani Lakshmibhai as his regent.[11]

Widowhood and annexation

The East India Company administration, led by Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, had for several years enforced a "doctrine of lapse", wherein Indian states whose Hindu rulers died without a natural heir were annexed by Britain. This policy was quickly enforced on Jhansi after Gangadhar Rao's death, to the Rani's dismay.[14] She wrote a letter to the Company protesting the annexation on 16 February 1854.[15] Dalhousie issued a lengthy minute in response eleven days later. He argued that since the British had conquered the Marathas, Jhansi's former overlords, the Company was now the "paramount power" with the authority to decide the succession. Dalhousie characterised Gangadhar Rao's rule as one of decline and mismanagement, and asserted that Jhansi and its people would benefit from direct British rule.[16]

Lakshmibhai fought the decision through diplomatic channels. She initiated coversations with Major Ellis, a sympathetic local Company official, and engaged John Lang, an Australian lawyer, to represent her.[17] She wrote multiple appeals to Dalhousie, outlining previous British treaties with Jhansi in 1803, 1817, and 1842 which recognised the rajas of Jhansi as legitimate rulers.[18] She also cited specific terminology and Hindu shastra tradition to argue that Damodar Rao should be entitled to the throne.[19] Dalhousie bluntly rejected these appeals without refuting the arguments contained within, but still the Rani peristed: her final appeals concluded that the annexation constituted a "gross violation ... of treaties" and that Jhansi was reduced to "subjection, dishonour, and poverty".[20]

None of these appeals came to fruition, and Jhansi lapsed to the Company in May 1854.[20] Granted a lifetime pension of five thousand rupees per month (or six thousand pounds yearly) by the new Company superintendent of Jhansi, Captain Alexander Skene, Lakshmibhai was required to vacate the fort but allowed to keep the two-storey palace.[21] She disagreed with the Company in the following years over various matters: on taxation and debts, the 1854 lifting of the ban on cattle slaughter in Jhansi, the British occupation of a temple outside the town, and of course the continued foreign rule.[22]

Later songs and poems retell Lakshmibhai's defiant mantra, "I will never give up my Jhansi!", which she is traditionally said to have cried during this period. She continued to train her all-female regiment, and paraded them on horseback through the town.[23]

1857 Indian Rebellion

On 10 May 1857, native sepoy troops stationed in Meerut mutinied against their British officers, sparking the Indian Rebellion.[24] The nascent rebellion swiftly grew as towns and troops across northern India, including Delhi, joined in. Nana Sahib organised massacres of the British at Kanpur, while similar events occurred in Lucknow; news of these killings had not reached Jhansi by the end of May.[25] The garrison, commanded by Skene, consisted of native troops of the 12th Native Infantry and the 14th Irregular Cavalry, and oversaw a strategic position at the junction of four major roads: northwest to Agra and Delhi, northeast to Kanpur and Lucknow, east to Allahabad, and south across the Deccan Plateau.[26]

Skene was not initially alarmed, and allowed the Rani to raise a bodyguard for her own protection.[27] However, on 5 June, a company of infantry took control of the ammunition store, and shot their British commanding officer when he attempted to reassert control the next day. The remaining sixty British men, women, and children took refuge in the main fort, where they were besieged.[28] According to a servant of a British captain, the Rani sent a letter claiming that the sepoys, accusing her of protecting the British, had surrounded her palace and demanded she provide assistance.[29] On 8 June, the British surrendered and asked for safe passage; after an unknown someone acquiesced, they were led to the Jokhan Bagh garden, where nearly all of them were killed.[30]

The Rani's involvement in this massacre is a subject of debate. S. Thornton, a tax collector in Samthar State, wrote that the Rani had instigated the revolt, while two somewhat questionable eyewitness accounts reported that she executed three British messengers and gave the rest false promise of safe passage.[31] Other contemporary reports claimed the Rani was innocent, while the official report by F.W. Pinkney came to no clear conclusion.[32] Lakshmibai herself claimed, in two mid-June letters to Major Erskine, commissioner of the Saugor division, that she had been at the mercy of the mutineers and could not help the besieged British. She wished damnation upon the mutineers, asserted that she was governing only while Company rule was absent, and asked for government assistance to combat prevalent disorder. Erskine believed her account, but his superiors in Fort William were less trusting.[33] Even if the Rani was not involved with the mutiny, its outcome had spectacularly coincided with her prior aims.[34]

After the rebels left, Erskine authorised the Rani to rule until the British returned. In this capacity, she collected taxes, repaired the fort, and distributed donations to the poor.[35] One of her generals named Jawahar Singh defeated Sadasheo Rao, a cousin of Gangadhar Rao, who tried to claim Jhansi for himself. This skirmish led the Rani to focus on re-establishing military authority, and so she ordered the recruitment of troops and the manufacturing of cannon and other weapons.[36] With this larger force of approximately 15,000 troops, Jhansi saw off an attack by nearby Orchha, who had remained loyal to the Company and whose leaders judged that the British would turn a blind eye to the war. Orchha invaded on 10 August and besieged Jhansi from early September to late October, when they were driven off by the raja of Banpur's troops.[37]

Conflict with the British

In September 1857, with Jhansi under Orchha siege, the Rani requested that Major Erskine send forces to help, as he had earlier promised when authorizing her rule. On 19 October, he replied in the negative, and further added that the conduct of all at Jhansi would be investigated.[38] Even though she feared the British regarded her as an enemy, the Rani was not yet ready to take the rebels' side, although she was dismayed by the British failures to reply.[39] Unable to persuade the Rani to commit to the rebellion, the raja of Banpur left Jhansi in January 1858. Some of her advisors advocated for peace with the Britis; others, including her father, for war.[40] Remaining rebel leaders had begun to gather at Jhansi, including the raja of Banpur, who returned with 3,500 men on 15 March. This encouraged the Rani, who was still of two minds: she continued to send unanswered conciliations to the British, while at the same time militantly preparing arms and ammunition.[41] Her position may have eventually been decided by her troops, who demanded to fight.[42]

Because of her conflict with the Company-loyal state of Orchha and her rescue by the rebel raja of Banpur, the British had likely decided that the Rani was an enemy.[43] Kanpur had been retaken on 16 July, followed by Lucknow and, on 22 September Delhi. Their attention now fell on the remaining pockets of resistance in Central India: Jhansi, a pivotal strategic location and the home of a ruler now seen as a "Jezebel", was a prime target.[44] Command of the Central India Field Force of 4,300 men was given to the capable Hugh Rose, who set out from Indore on 6 January 1858.[45] He relieved Sagar on 3 February, defeated the army of Shahgarh and sacked Banpur in early March, and then marched on Jhansi.[46]

Rose's army, by now numbering around 3,000 men, approached Jhansi from several directions. Reconnaissance found that not only were the defences in excellent condition, with 25-foot (7.6 m) loopholed granite walls topped by large guns and batteries able to enfilade each other, but the surrounding countryside had been removed of all cover and foliage.[48] The inhabitants of the town, including 11,500 soldiers, had stockpiled hundreds of tons of supplies in preparation for the upcoming siege.[49] It began on 22 March with consistent artillery fire against Jhansi's ramparts. Although the Rani's forces returned fire capably, her best gunners were soon killed, and the defender's situation became increasingly dire. A breach was made on 29 March, although it was quickly stockaded. Rose was making preparations for an assault when news reached him that the Rani's childhood friend Tatya Tope was marching to rescue Jhansi with more than 20,000 men.[50]

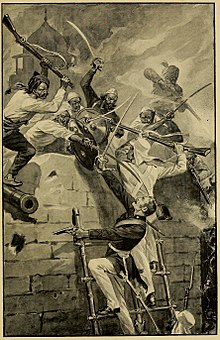

Rose, unable to confront the new enemy with his whole force for fear that the defenders of Jhansi would sortie into his rear, detached just 1,200 men to confront Tatya Tope. Despite the numerical advantages of the rebel force, the vast majority of them was untrained, and they used old, slow guns. In the Battle of Betwa on 1 April, accurate British artillery fire repelled the first rebel line, and organisational mistakes meant the second line was unable to assist. In a comprehensive victory, the British lost less than one hundred men, and inflicted over 1,500 casualties on Tatya Tope's army.[51] At 3am on 3 April, two columns assaulted the south wall—one through the breach and one using ladders in an escalade—and both penetrated the defences. The Rani personally led a counter-attack with 1,500 Afghan troops, but steady British reinforcement drove them back.[52]

Determined resistance was encountered in every street and every room of the palace. Street fighting continued into the following day and no quarter was given, even to women and children. "No maudlin clemency was to mark the fall of the city," wrote Thomas Lowe.[53] The Rani withdrew from the palace to the fort and after taking counsel decided that since resistance in the city was useless she must leave and join either Tatya Tope or Rao Sahib (Nana Sahib's nephew).[54]

According to tradition, with Damodar Rao on her back she jumped on her horse Baadal from the fort; they survived but the horse died.[55] The Rani escaped in the night with her son, surrounded by guards.[56] The escort included the warriors Khuda Bakhsh Basharat Ali (commandant), Ghulam Gaus Khan, Dost Khan, Lala Bhau Bakshi, Moti Bai, Sunder-Mundar, Kashi Bai, Deewan Raghunath Singh and Deewan Jawahar Singh. She decamped to Kalpi with a few guards, where she joined additional rebel forces, including Tatya Tope.[54] They occupied the town of Kalpi and prepared to defend it. On 22 May British forces attacked Kalpi; the forces were commanded by the Rani herself and were again defeated.

Flight to Gwalior and death

The leaders (the Rani of Jhansi, Tatiya Tope, the Nawab of Banda, and Rao Sahib) fled once more. They came to Gwalior and joined the Indian forces who now held the city (Maharaja Scindia having fled to Agra from the battlefield at Morar). They moved on to Gwalior intending to occupy the strategic Gwalior Fort and the rebel forces occupied the city without opposition. The rebels proclaimed Nana Sahib as Peshwa of a revived Maratha dominion with Rao Sahib as his governor (ਸੂਬੇਦਾਰ) in Gwalior. The Rani was unsuccessful in trying to persuade the other rebel leaders to prepare to defend Gwalior against a British attack which she expected would come soon. General Rose's forces took Morar on 16 June and then made a successful attack on the city.[57]

On 17 June in Kotah-ki-Serai near the Phool Bagh of Gwalior, a squadron of the 8th (King's Royal Irish) Hussars, under Captain Heneage, fought the large Indian force commanded by Rani Lakshmibai, who was trying to leave the area. The 8th Hussars charged into the Indian force, slaughtering 5,000 Indian soldiers, including any Indian "over the age of 16".[58] They took two guns and continued the charge right through the Phool Bagh encampment. In this engagement, according to an eyewitness account, Rani Lakshmibai put on a sowar's uniform and attacked one of the hussars; she was unhorsed and also wounded, probably by his sabre. Shortly afterwards, as she sat bleeding by the roadside, she recognized the soldier and fired at him with a pistol, whereupon he "dispatched the young lady with his carbine".[59][60] According to another tradition Rani Lakshmibai, the Queen of Jhansi, dressed as a cavalry leader, was badly wounded; not wishing the British to capture her body, she told a hermit to burn it. After her death, a few local people cremated her body.

The British captured the city of Gwalior after three days. In the British report of this battle, Hugh Rose commented that Rani Lakshmibai is "personable, clever and beautiful" and she is "the most dangerous of all Indian leaders".[61][62]

Cultural depictions and statues

-

An equestrian statue of Lakshmibai in Solapur, Maharashtra

-

The statue of Rani Lakshmibai, Shimla

-

Birthplace of Rani Lakshmibai, Varanasi

-

Rani Lakshmi Bai Park, Jhansi

-

1957 Commemorative postal stamp

Statues of Lakshmibai are seen in many places in India, which show her and her son tied to her back. Lakshmibai National University of Physical Education in Gwalior, Laksmibai National College of Physical Education in Thiruvananthapuram, Maharani Laxmi Bai Medical College in Jhansi are named after her. Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agricultural University in Jhansi was founded in 2013. The Rani Jhansi Marine National Park is located in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal.

Rani of Jhansi Regiment

The Rani of Jhansi Regiment was a unit of the Indian National Army, which was formed in 1942 by Indian nationalists in Southeast Asia during World War II. The regiment was named in honor of Rani Lakshmibai, the warrior queen of Jhansi who fought against British colonial rule in India in 1857. The Rani of Jhansi Regiment was the first all-women regiment in the history of the Indian Army. It was composed of Indian women who were recruited from Southeast Asia, mostly from the Indian diaspora in Singapore and Malaya. The women were trained in military tactics, physical fitness, and marksmanship, and were deployed in Burma and other parts of Southeast Asia to fight against the British.[63]

The Indian Coast Guard ship ICGS Lakshmi Bai has been named after her.

In 1957 two postage stamps were issued to commemorate the centenary of the rebellion. Indian representations in novels, poetry, and film tend towards an uncomplicated valorization of Rani Lakshmibai as an individual solely devoted to the cause of Indian independence.[64]

Songs and poems

Several patriotic songs have been written about the Rani. The most famous composition about Rani Lakshmi Bai is the Hindi poem Jhansi ki Rani written by Subhadra Kumari Chauhan. An emotionally charged description of the life of Rani Lakshmibai, it is often taught in schools in India.[65] A popular stanza from it reads:

बुंदेले हरबोलों के मुँह हमने सुनी कहानी थी, खूब लड़ी मर्दानी वह तो झाँसी वाली रानी थी।।[66]

Translation: "From the Bundele Harbolas' mouths we heard stories / She fought like a man, she was the Rani of Jhansi."[67]

For Marathi people, there is an equally well-known ballad about the brave queen penned at the spot near Gwalior where she died in battle, by B. R. Tambe, who was a poet laureate of Maharashtra and of her clan. A couple of stanzas run like this:

हिंदबांधवा, थांब या स्थळीं अश्रु दोन ढाळीं /

ती पराक्रमाची ज्योत मावळे इथे झाशिवाली / ... / घोड्यावर खंद्या स्वार, हातात नंगि तर्वार / खणखणा करित ती वार / गोर्यांची कोंडी फोडित पाडित वीर इथे आली /

मर्दानी झाशीवाली!

Translation: "You, a denizen of this land, pause here and shed a tear or two / For this is where the flame of the valorous lady of Jhansi was extinguished / … / Astride a stalwart stallion / With a naked sword in hand / She burst open the British siege / And came to rest here, the brave lady of Jhansi!"

See also

- Indian independence movement

- Gangadhar Rao, Maharaja of Jhansi

- Jhalkaribai, a soldier of the Rani

- Central India Campaign (1858)

- Company rule in India

- Rani Velu Nachiyar

- Vellore mutiny of 1806

- Tirot Sing, Khasi chief who resisted the British during the Anglo-Khasi War

- Tantia Tope

References

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 15; Singh 2014, p. 12; Singh 2020, p. 25.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 15; Singh 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 2; Singh 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 16.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 16–17; Lebra 2008, p. 2; Singh 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 17–18; Singh 2020, p. 25.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 17–19; Singh 2014, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 19.

- ^ a b Singh 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 20; Lebra 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 20, 25.

- ^ Lebra 2008, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Singh 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 26–28; Singh 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 29–30; Lebra 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 34; Singh 2014, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Lebra 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 39; David 2003, p. 250.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 40–45.

- ^ Lebra 2008, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 48–49; David 2003, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 49; David 2003, p. 351.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 51–52; David 2003, p. 351.

- ^ Lebra 2008, pp. 4–5; David 2003, p. 351.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 5; Singh 2014, p. 14; David 2003, p. 351.

- ^ Singh 2014, pp. 14–15; David 2003, p. 351.

- ^ Singh 2014, p. 15; David 2003, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 58–60; David 2003, p. 352.

- ^ David 2003, p. 352.

- ^ Lebra 2008, pp. 5–6; Singh 2014, p. 15; David 2003, p. 352.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 74; Lebra 2008, p. 5; Singh 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 77–78; David 2003, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Lebra 1986, p. 78; David 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Lebra 2008, p. 6; David 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 81–83; David 2003, pp. 354–355.

- ^ David 2003, p. 355.

- ^ David 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 79–80; David 2003, p. 354.

- ^ David 2003, pp. 354–356.

- ^ David 2003, p. 358.

- ^ David 2003, p. 356; Lebra 2008, p. 6.

- ^ David 2003, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Lebra 1986, pp. 87–89; David 2003, pp. 356–357.

- ^ David 2003, pp. 357–358; Lebra 2008, p. 6.

- ^ David 2003, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Edwardes, Michael (1975) Red Year. London: Sphere Books, pp. 120–21

- ^ a b Edwardes, Michael (1975) Red Year. London: Sphere Books, pp. 119 & 121

- ^ "Jhansi". Remarkable India. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Rani of Jhansi, Rebel against will by Rainer Jerosch, published by Aakar Books 2007; chapters 5 and 6

- ^ Edwardes, Michael (1975) Red Year. London: Sphere Books, pp. 124–25

- ^ Gold, Claudia, (2015) Women Who Ruled: History's 50 Most Remarkable Women ISBN 978-1784290863 p. 253

- ^ David (2006), pp. 351–362

- ^ Copsey, Allen. "Brigadier M W Smith Jun 25th, 1858 to Gen. Hugh Rose". Copsey-family.org. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ David, Saul (2003), The Indian Mutiny: 1857, London: Penguin; p. 367

- ^ Ashcroft, Nigel (2009), Queen of Jhansi, Mumbai: Hollywood Publishing;

- ^ Gupta, Ateendriya (7 March 2020). "Women in command: Remembering the Rani of Jhansi Regiment". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ The Rani of Jhansi: Gender, History, and Fable in India (Harleen Singh, Cambridge University Press, 2014)

- ^ "Poems of Bundelkhand". www.bundelkhand.in. Bundelkhand.In. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Chauhan, Subhadra Kumari. "Jhansi ki rani". www.poemhunter.com. Poem hunter. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ चौहान, सुभद्रा कुमारी; Chauhan, Subhadra Kumari (2014). मुकुल तथा अन्य कविताएं (Hindi Poetry): Mukul Tatha Anya Kavitayein (Hindi Poetry) (in Hindi). Bhartiya Sahitya Inc. ISBN 978-1-61301-461-5.

Sources

- David, Saul (2003). The Indian Mutiny: 1857. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-1410-0554-6.

- Lebra, Joyce (1986). The Rani of Jhansi: A Study in Female Heroism in India. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0984-3.

- Lebra, Joyce (2008). Women Against the Raj: The Rani of Jhansi Regiment. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. ISBN 978-9-8123-0810-8.

- Singh, Harleen (2014). The Rani of Jhansi: Gender, History, and Fable in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1073-3749-7.

- Singh, Harleen (2020). "India's Rebel Queen: Rani Lakshmi Bai and the 1857 Uprising". Women Warriors and National Heroes: Global Histories. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 23–38. ISBN 978-1-3501-2113-3.

- 1858 deaths

- 19th-century women regents

- 19th-century Indian women

- History of Uttar Pradesh

- Queens consort of India

- Indian rebels

- Indian women warriors

- Jhansi

- Marathi people

- Military personnel from Uttar Pradesh

- People from Varanasi

- People from the Maratha Confederacy

- Revolutionaries of the Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Women in 19th-century warfare

- Women Indian independence activists

- Women from Uttar Pradesh

- Women from the Maratha Empire

- Indian independence armed struggle activists

- Regents of India

- Deaths by firearm in India