Louis-Émile Bertin

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

Louis-Émile Bertin | |

|---|---|

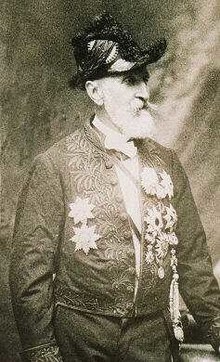

Louis-Émile Bertin in Institut de France uniform, post 1903 | |

| Born | 23 March 1840 |

| Died | 22 October 1924 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation | naval engineer |

Louis-Émile Bertin (23 March 1840 – 22 October 1924) was a French naval engineer, one of the foremost of his time, and a proponent of the "Jeune École" philosophy of using light, but powerfully armed warships instead of large battleships.

Early life[edit]

Bertin was born in Nancy, France, on 23 March 1840. He entered the Paris École polytechnique in 1858. At exiting the school, he chose the field of Naval Engineering (Corps du génie maritime). His role model was Henri Dupuy de Lôme, who had designed the first ironclad warship in France. Bertin came to be known for his innovative designs, often at odds with conventional wisdom, and won international recognition as a leading naval architect. In 1871, he also became a doctor of laws, showing great versatility of talents.

Life in Japan[edit]

In 1885, the Japanese government persuaded the French Génie Maritime to send Bertin as a special foreign advisor to the Imperial Japanese Navy for a period of four years from 1886 to 1890. Bertin was tasked with training Japanese engineers and naval architects, designing and constructing modern warships, and naval facilities. For Bertin, then aged 45, it was an extraordinary opportunity to design an entire navy. For the French government, it represented a major coup in their fight against Great Britain and Germany for influence over the newly-industrializing Empire of Japan.

While in Japan, Bertin designed and constructed seven major warships and 22 torpedo boats, which formed the nucleus of the budding Imperial Japanese Navy. These included the three Matsushima-class protected cruisers, which featured a single but immensely powerful 12.6-inch (320 mm) Canet main gun, which formed the core of the Japanese fleet during the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895.

Bertin also directed the construction of the naval shipyards and arsenals of Kure and Sasebo.

However, Bertin's time in Japan was also plagued by political intrigue. There were strong factions with the Japanese government who favored the British or Germans over the French, or who still begrudged the French for their previous strong support of the Tokugawa bakufu. Bertin's position was more than once put into jeopardy. That Japan was gambling on the yet-untested Jeune École philosophy in approving Bertin's designs was also of concern.

His efforts in building up the Imperial Japanese Navy, made a decisive contribution to the Japanese victory at the Battle of the Yalu, 17 September 1894, Japanese Admiral Itō Sukeyuki, (who had been on board the flagship Matsushima) wrote to Bertin:

- "The ships fulfilled all our hopes. They were the formidable elements of our fleet; because of their powerful armament and intelligent design, we were able to win a brilliant victory against the Chinese armoured ships". (Yuko Ito[1])

Émile Bertin received the Order of the Rising Sun, second class, from the Meiji Emperor at the end of 1890. During the ceremony, the Navy Minister Saigo Tsugumichi (1843–1902) declared:

- "Not only did Bertin establish the plans for the construction of coastal ships and first-class cruisers, he also made suggestions for the organization of the fleet, the defense of our coasts, the construction of high-caliber guns, the usage of materials such as steel or coal.; during the four years he has been in Japan, he never stopped working for the technical improvement of the Navy, and the results of his efforts are remarquable" (Tokyo, January 23, 1890[2])

Warships designed or built while in Japan[edit]

- 3 cruisers: the 4,700-ton Matsushima and Itsukushima, made in France, and Hashidate, built by Japan in Yokosuka, Japan.

- 3 coastal warships of 4,278 tons.

- 2 small cruisers: Chiyoda, a small cruiser of 2,439 tons built in Great Britain, and Yaeyama, 1,800 tons, built at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, Japan.

- 1 light cruiser: Chishima, built in France.

- 1 frigate, the 1,600-ton Takao, built in Yokosuka.

- 16 torpedo boats of 54 tons each, built in France by the Companie du Creusot in 1888, and assembled in Japan.

Subsequent life[edit]

Upon his return to France, Bertin was promoted to Director of the School of Naval Engineering (Ecole du Génie Maritime). In 1895 he became the Director of Naval Construction (Directeur des Constructions Navales) with the rank of General Engineer (ingénieur général). During his tenure as Director, the French Navy became the second navy in the world in terms of tonnage. Back in France, ironically he found himself at odds with the supporters of Admiral Hyacinthe Aube's Jeune École, and he more than once criticized the designs of his fellow constructors; his criticisms were later justified by the catastrophic sinking of the battleship Bouvet in 1915. He was inducted in the famous Institut de France in 1903.

Legacy[edit]

Bertin's concept of lightly armored, heavily-gunned cruisers was soon overtaken by the pre-dreadnoughts; by the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the concepts of the Jeune École had largely been discredited. The Japanese were not happy with the overall performance of the Matsushima-class vessels, and after the cruiser Unebi sank en route from France to Japan in December 1886, Bertin's later designs were ordered from British, rather than French shipyards.

Bertin's real legacy for Japan was his creation of a series of modern shipyards, most notably Kure and Sasebo (Yokosuka, Japan's first modern arsenal, was built earlier in 1865 by the French engineer Léonce Verny). During World War I, those very yards built twelve Arabe-class destroyers for France's embattled fleet.

After his death, a light cruiser of the French Navy, Émile Bertin, was named in his honour. Émile Bertin also invented the twin-oscillographer (to study roll and pitch). The cruiser named in his honour would be, in 1940, the ship that transferred the gold reserves of the Bank of France to the Martinique, preventing Nazi Germany from seizing the precious metal, of which France retained an important amount.

Works[edit]

Louis-Émile Bertin also wrote several books:

- "Données Expérimentales sur les vagues et le roulis" (1874)

- "La Marine à Vapeur de Guerre et de Commerce" (1875)

- "Les Grandes Guerres Civiles du Japon" (1894)

- "Chaudières Marines, Cours de Machine à Vapeur" (1896)[3]

- "État actuel de la marine de guerre"

- "Évolution de la puissance défensive des navires de guerre" (1906)

- "La marine moderne" (1910)

- "La marine moderne. Ancienne histoire et questions neuves" (1920)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "La Marine moderne d'Émile Bertin", pp. 167–170

- ^ "France-Japon Eco, No97, p. 82

- ^ Marine boilers—their construction and working: https://archive.org/details/marineboilersthe00bertuoft

References[edit]

- Dedet, Christian. Les fleurs d'acier du Mikado (Paris: Flammarion, 1993) (in French)

- Bernard, Hervé. Historien de marine écrivain. L'ingénieur général du Génie maritime Louis, Emile Bertin (1840–1924) créateur de la marine militaire du Japon à l'ère de Meiji Tenno (en quadrichromie 84 pages, autoédition 2007, imprimerie Biarritz) (in French).

- Bernard, Hervé. Historien de marine écrivain. Ambassadeur au Pays du Soleil Levant dans l'ancien Empire du Japon (en quadrichromie, 266 pages, autoédition 2007, imprimerie Biarritz) (in French).

Further reading[edit]

Arthur, Birembaut (1970–1980). "Bertin, Louis-Émile". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.