Pulmonary fibrosis

| Pulmonary fibrosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis |

| |

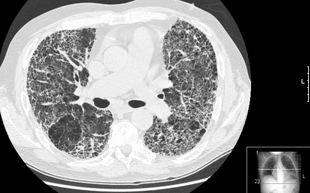

| Lung with end-stage pulmonary fibrosis at autopsy | |

| |

| Clubbing of the fingers in pulmonary fibrosis | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, dry cough, feeling tired, weight loss, nail clubbing[1] |

| Complications | Pulmonary hypertension, respiratory failure, pneumothorax, lung cancer[2] |

| Causes | Tobacco smoking, environmental pollution, certain medications, connective tissue diseases, interstitial lung disease, unknown[1][3] |

| Treatment | Oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, lung transplantation[4] |

| Medication | Pirfenidone, nintedanib[4] |

| Prognosis | Poor[3] |

| Frequency | >5 million people[5] |

Pulmonary fibrosis is a condition in which the lungs become scarred over time.[1] Symptoms include shortness of breath, a dry cough, feeling tired, weight loss, and nail clubbing.[1] Complications may include pulmonary hypertension, respiratory failure, pneumothorax, and lung cancer.[2]

Causes include environmental pollution, certain medications, connective tissue diseases, infections, and interstitial lung diseases.[1][3][6] But in most cases the cause is unknown (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis).[1][3] Diagnosis may be based on symptoms, medical imaging, lung biopsy, and lung function tests.[1]

No cure exists and treatment options are limited.[1] Treatment is directed toward improving symptoms and may include oxygen therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation.[1][4] Certain medications may slow the scarring.[4] Lung transplantation may be an option.[3] At least 5 million people are affected globally.[5] Life expectancy is generally less than five years.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis are mainly:[1]

- Shortness of breath, particularly with exertion

- Chronic dry, hacking coughing

- Fatigue and weakness

- Chest discomfort, including chest pain

- Loss of appetite and rapid weight loss

Pulmonary fibrosis is suggested by a history of progressive shortness of breath (dyspnea) with exertion. Sometimes fine inspiratory crackles can be heard at the lung bases on auscultation. A chest X-ray may not be abnormal, but high-resolution CT will often show abnormalities.[3]

Cause

[edit]Pulmonary fibrosis may be a secondary effect of other diseases. Most of these are classified as interstitial lung diseases. Examples include autoimmune disorders, viral infections, and bacterial infections such as tuberculosis that may cause fibrotic changes in the lungs' upper or lower lobes and other microscopic lung injuries. But pulmonary fibrosis can also appear without any known cause. In that case, it is termed "idiopathic".[7] Most idiopathic cases are diagnosed as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. This is a diagnosis of exclusion of a characteristic set of histologic/pathologic features known as usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). In either case, a growing body of evidence points to a genetic predisposition in a subset of patients. For example, a mutation in surfactant protein C (SP-C) has been found in some families with a history of pulmonary fibrosis.[8] Autosomal dominant mutations in the TERC or TERT genes, which encode telomerase, have been identified in about 15% of pulmonary fibrosis patients.[9]

Diseases and conditions that may cause pulmonary fibrosis as a secondary effect include:[3][8]

- Inhalation of environmental and occupational pollutants, such as metals[10] in asbestosis, silicosis, and exposure to certain gases. Coal miners, ship workers and sand blasters, among others, are at higher risk.[7]

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, most often resulting from inhaling dust contaminated with bacterial, fungal, or animal products

- Cigarette smoking can increase the risk or make the illness worse.[7] Smoking is a known cause of some types of lung fibrosis, such as smoking-related interstitial fibrosis (SRIF).[11]

- Some typical connective tissue diseases[7] such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, SLE and scleroderma

- Other diseases that involve connective tissue, such as sarcoidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Infections, including COVID-19

- Certain medications, e.g. amiodarone, bleomycin (pingyangmycin), busulfan, apomorphine,[12] and nitrofurantoin[13]

- Radiation therapy to the chest

Pathogenesis

[edit]Pulmonary fibrosis involves a gradual replacement of normal lung tissue with fibrotic tissue. Such scar tissue causes an irreversible decrease in oxygen diffusion capacity, and the resulting stiffness or decreased compliance makes pulmonary fibrosis a restrictive lung disease.[14] Pulmonary fibrosis is perpetuated by aberrant wound healing, rather than chronic inflammation.[15] It is the main cause of restrictive lung disease that is intrinsic to the lung parenchyma. In contrast, quadriplegia[16] and kyphosis[17] are examples of causes of restrictive lung disease that do not necessarily involve pulmonary fibrosis.

Common genes implicated in fibrosis are Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β),[18] Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF),[19] Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR),[20] Interleukin-13 (IL-13),[21] Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF),[22] Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway,[23] and TNIK.[24] Additionally, chromatin remodeler proteins affect the development of lung fibrosis, as they are crucial for gene expression regulation and their dysregulation can contribute to fibrotic disease progression.[25]

- TGF-β is a cytokine that plays a critical role in the regulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) production and cellular differentiation.[26] It is a potent stimulator of fibrosis, and increased TGF-β signaling is associated with the development of fibrosis in various organs.

- CTGF is a matricellular protein involved in ECM production and remodeling.[26] It is up-regulated in response to TGF-β and has been implicated in the development of pulmonary fibrosis.[18]

- EGFR is a transmembrane receptor that plays a role in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Dysregulated EGFR signaling has been implicated in the development of pulmonary fibrosis, and drugs that target EGFR have been shown to have therapeutic potential in the treatment of the disease.[20]

- IL-13 is a cytokine involved in regulating immune responses.[21] It has been shown to promote fibrosis in the lungs by stimulating the production of ECM proteins and the recruitment of fibroblasts to sites of tissue injury.

- PDGF is a cytokine that plays a key role in the regulation of cell proliferation and migration.[22] It is involved in the recruitment of fibroblasts to sites of tissue injury in the lungs, and increased PDGF signaling is associated with the development and progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

- Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role in tissue repair and regeneration, and dysregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been implicated in the development of pulmonary fibrosis.[23]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The diagnosis can be confirmed by lung biopsy.[3] A video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) under general anesthesia may be needed to obtain enough tissue to make an accurate diagnosis. This kind of biopsy involves placement of several tubes through the chest wall, one of which is used to cut off a piece of lung for evaluation. The removed tissue is examined histopathologically by microscopy to confirm the presence and pattern of fibrosis as well as other features that may indicate a specific cause, such as specific types of mineral dust or possible response to therapy, e.g. a pattern of so-called non-specific interstitial fibrosis.

Misdiagnosis is common because, while pulmonary fibrosis is not rare, each type is uncommon and evaluation of patients with these diseases is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Terminology has been standardized but difficulties still exist in their application. Even experts may disagree on the classification of some cases.[27]

On spirometry, as a restrictive lung disease, both the FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) and FVC (forced vital capacity) are reduced so the FEV1/FVC ratio is normal or even increased, in contrast to obstructive lung disease, where this ratio is reduced. The values for residual volume and total lung capacity are generally decreased in restrictive lung disease.[28]

Treatment

[edit]Pulmonary fibrosis creates scar tissue. The scarring is permanent once it has developed.[29] Slowing the progression and prevention depends on the underlying cause:

- Treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are very limited, since no current treatment has stopped the progression of the disease. Because of this, there is no evidence that any medication can significantly help this condition, despite ongoing research trials. Lung transplantation is the only therapeutic option available in severe cases. A lung transplant can improve the patient's quality of life.[30]

- Immunosuppressive drugs can also be considered. These are sometimes prescribed to slow the processes that lead to fibrosis. Some types of lung fibrosis respond to corticosteroids, such as prednisone.[29]

- Oxygen therapy is also an option. The patient may choose how much oxygen to use. The use of oxygen doesn't repair the lung damage, but can:

- make breathing and exercise easier;

- prevent or lessen complication from low blood oxygen levels;

- reduce blood pressure; and

- improve sleep and sense of well-being. [30]

The immune system is thought to play a central role in the development of many forms of pulmonary fibrosis. The goal of treatment with immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids is to decrease lung inflammation and subsequent scarring. Responses to treatment vary. Those whose conditions improve with immunosuppressive treatment probably do not have idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis has no significant treatment or cure. [30]

- Two pharmacological agents intended to prevent scarring in mild idiopathic fibrosis are pirfenidone, which reduced reductions in the 1-year rate of decline in FVC and reduced the decline in distances on the 6-minute walk test, but had no effect on respiratory symptoms,[31] and is nintedanib, which acts as an antifibrotic, mediated through the inhibition of a variety of tyrosine kinase receptors (including platelet-derived growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor).[32] A randomized clinical trial showed it reduced lung-function decline and acute exacerbations.[33]

- Preclinical studies on monoclonal antibodies that target the pulmonary endothelial aggregation receptor 1 (PEAR1) (which plays a crucial role in fibroblast activation and the progression of fibrosis) have shown promising results in slowing disease progression and improving lung function. [34]

- Anti-inflammatory agents have only limited success in reducing the fibrotic process. Some other types of fibrosis, such as non-specific interstitial pneumonia, may respond to immunosuppressive therapy such as corticosteroids. But only a minority of patients respond to corticosteroids alone, so additional immunosuppressants, such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate, penicillamine, and cyclosporine may be used. Colchicine has also been used with limited success.[3] Trials with newer drugs such as IFN-γ and mycophenolate mofetil are ongoing.

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, a less severe form of pulmonary fibrosis, is prevented from becoming aggravated by avoiding contact with the causative material.

Prognosis

[edit]Hypoxia caused by pulmonary fibrosis can lead to pulmonary hypertension, which in turn can lead to heart failure of the right ventricle. Hypoxia can be prevented by oxygen supplementation.[3]

Pulmonary fibrosis may also result in an increased risk of pulmonary emboli, which can be prevented by anticoagulants.[3]

Epidemiology

[edit]Globally, the prevalence and incidence of pulmonary fibrosis has been studied in the United States, Norway, Czech Republic, Greece, United Kingdom, Finland, and Turkey, with only two studies in Japan and Taiwan. But most of these studies were of people already diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis, which lowers the diagnosis sensitivity, so that the prevalence and incidence has ranged from 0.7 per 100,000 in Taiwan to 63.0 per 100,000 in the U.S., and the published incidence has ranged from 0.6 per 100,000 person years to 17.4 per 100,000 person years.[35]

The mean age of all pulmonary fibrosis patients is between 65 and 70 years, making age a criterion of its own. Aging respiratory systems are much more vulnerable to fibrosis and stem cell depletion.

| Incidence rate | Prevalence rate | Population | Years covered | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.8–16.3 | 14.0–42.7 | U.S. health care claims processing system | 1996–2000 | Raghu et al.[37] |

| 8.8–17.4 | 27.9–63.0 | Olmsted County, Minnesota | 1997–2005 | Fernandez Perez et al.[38] |

| 27.5 | 30.3 | Males in Bernalillo County, New Mexico | 1988–1990 | Coultas et al.[39] |

| 11.5 | 14.5 | Females |

Based on these rates, pulmonary fibrosis prevalence in the U.S. could range from more than 29,000 to almost 132,000, based on the population in 2000 that was 18 years or older. The actual number may be significantly higher due to misdiagnosis. Typically, patients are in their forties and fifties when diagnosed, while the incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis increases dramatically after age 50. But loss of pulmonary function is commonly ascribed to old age, heart disease, or more common lung diseases.[40]

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, deaths of people with pulmonary fibrosis increased due to the rapid loss of pulmonary function. The consequences of COVID-19 include a large cohort of patients with both fibrosis and progressive lung impairment. Long-term follow-up studies are showing long-term impairment of lung function and radiographic abnormalities suggestive of pulmonary fibrosis for patients with lung comorbidities.[41]

The most common long-term consequence in COVID-19 patients is pulmonary fibrosis. The biggest concerns about pulmonary fibrosis and the increase of respiratory follow-up after COVID-19 are expected to be solved in the near future. Older age with decreased lung function and/or preexisting comorbidities, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and obesity increase the risk of developing fibrotic lung alterations in COVID-19 survivors with lower exercise tolerance. According to one study, 40% of COVID-19 patients develop a form of fibrosis of the lungs, and 20% of those are severe.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Pulmonary Fibrosis". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Pulmonary fibrosis – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Pulmonary Fibrosis". MedicineNet, Inc. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Pulmonary fibrosis – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic". mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b "American Thoracic Society – General Information about Pulmonary Fibrosis". thoracic.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Ahmad Alhiyari M, Ata F, Islam Alghizzawi M, Bint I Bilal A, Salih Abdulhadi A, Yousaf Z (31 December 2020). "Post COVID-19 fibrosis, an emerging complicationof SARS-CoV-2 infection". IDCases. 23: e01041. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e01041. ISSN 2214-2509. PMC 7785952. PMID 33425682.

- ^ a b c d MedlinePlus > Pulmonary Fibrosis Archived 5 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine Date last updated: 9 February 2010

- ^ a b "Causes". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". Genetics Home Reference, United States National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Hubbard R, Cooper M, Antoniak M, et al. (2000). "Risk of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in metal workers". Lancet. 355 (9202): 466–467. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82017-6. PMID 10841131. S2CID 10418808.

- ^ Vehar SJ, Yadav R, Mukhopadhyay S, Nathani A, Tolle LB (December 2022). "Smoking-Related Interstitial Fibrosis (SRIF) in Patients Presenting With Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease". Am J Clin Pathol. 159 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqac144. PMC 9891418. PMID 36495281.

- ^ "Not Found – BIDMC". bidmc.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ Goemaere NN, Grijm K, van Hal PT, den Bakker MA (2008). "Nitrofurantoin-induced pulmonary fibrosis: a case report". J Med Case Rep. 2: 169. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-169. PMC 2408600. PMID 18495029.

- ^ "Complications". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Gross TJ, Hunninghake GW (2001). "Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". N Engl J Med. 345 (7): 517–525. doi:10.1056/NEJMra003200. PMC 2231521. PMID 16928146.

- ^ Walker J, Cooney M, Norton S (August 1989). "Improved pulmonary function in chronic quadriplegics after pulmonary therapy and arm ergometry". Paraplegia. 27 (4): 278–83. doi:10.1038/sc.1989.42. PMID 2780083.

- ^ eMedicine Specialties > Pulmonology > Interstitial Lung Diseases > Restrictive Lung Disease Archived 5 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Author: Lalit K Kanaparthi, MD, Klaus-Dieter Lessnau, MD, Sat Sharma, MD. Updated: 27 July 2009

- ^ a b Saito A, Horie M, Nagase T (August 2018). "TGF-β Signaling in Lung Health and Disease". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 19 (8): 2460. doi:10.3390/ijms19082460. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 6121238. PMID 30127261.

- ^ Yang J, Velikoff M, Canalis E, Horowitz JC, Kim KK (15 April 2014). "Activated alveolar epithelial cells initiate fibrosis through autocrine and paracrine secretion of connective tissue growth factor". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 306 (8): L786–L796. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00243.2013. ISSN 1040-0605. PMC 3989723. PMID 24508728.

- ^ a b Schramm F, Schaefer L, Wygrecka M (January 2022). "EGFR Signaling in Lung Fibrosis". Cells. 11 (6): 986. doi:10.3390/cells11060986. ISSN 2073-4409. PMC 8947373. PMID 35326439.

- ^ a b Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, Shipley JM, Gotwals P, Noble P, Chen Q, Senior RM, Elias JA (17 September 2001). "Interleukin-13 Induces Tissue Fibrosis by Selectively Stimulating and Activating Transforming Growth Factor β1". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 194 (6): 809–822. doi:10.1084/jem.194.6.809. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2195954. PMID 11560996.

- ^ a b Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C (15 May 2008). "Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine". Genes & Development. 22 (10): 1276–1312. doi:10.1101/gad.1653708. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 2732412. PMID 18483217.

- ^ a b Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Shu G, Yin G (3 January 2022). "Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities". Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 7 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00762-6. ISSN 2059-3635. PMC 8724284. PMID 34980884.

- ^ Ren F, Aliper A, Chen J, Zhao H, Rao S, Kuppe C, Ozerov IV, Zhang M, Witte K, Kruse C, Aladinskiy V, Ivanenkov Y, Polykovskiy D, Fu Y, Babin E (8 March 2024). "A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models". Nature Biotechnology: 1–13. doi:10.1038/s41587-024-02143-0. ISSN 1546-1696. PMID 38459338.

- ^ Trejo-Villegas OA, Heijink IH, Ávila-Moreno F (22 June 2024). "Preclinical evidence in the assembly of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes: Epigenetic insights and clinical perspectives in human lung disease therapy". Molecular Therapy. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.06.026. ISSN 1525-0016.

- ^ a b Todd NW, Luzina IG, Atamas SP (23 July 2012). "Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis". Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair. 5 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1755-1536-5-11. ISSN 1755-1536. PMC 3443459. PMID 22824096.

- ^ "Tests and diagnosis". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "spirXpert.com". Archived from the original on 28 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Pulmonary Fibrosis". MedicineNet, Inc. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b c "Pulmonary fibrosis – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic". mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. (May 2014). "A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis" (PDF). NEJM. 370 (22): 2083–2092. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. PMID 24836312.

- ^ Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, et al. (2011). "Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". N Engl J Med. 365 (12): 1079–1087. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1103690. PMID 21992121.

- ^ Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. (May 2014). "Efficacy and Safety of Nintedanib in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis" (PDF). N Engl J Med. 370 (22): 2071–2082. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. hdl:11365/974374. PMID 24836310.

- ^ Yan G, Lin L, Jie Y, et al. (November 2022). "PEAR1 regulates expansion of activated fibroblasts and deposition of extracellular matrix in pulmonary fibrosis". Nature Communications. 13. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34870-w. PMC 9675736.

- ^ Ley B (2013). "Epidemiology of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis". Clinical Epidemiology. 5: 483–492. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S54815. PMC 3848422. PMID 24348069.

- ^ Vasarmidi E, Tsitoura E, Spandidos DA, Tzanakis N, Antoniou KM (September 2020). "Pulmonary fibrosis in the aftermath of the COVID-19 era (Review)". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 20 (3): 2557–2560. doi:10.3892/etm.2020.8980. ISSN 1792-0981. PMC 7401793. PMID 32765748.

- ^ Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and Prevalence of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:810-6.

- ^ Fernandez Perez ER, Daniels CE, Schroeder DR, St Sauver J, Hartman TE, Bartholmai BJ, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Incidence, Prevalence, and Clinical Course of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Population-Based Study. Chest. Jan 2010;137:129-37.

- ^ Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The Epidemiology of Interstitial Lung Diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Oct 1994;150(4):967-72. cited by Michaelson JE, Aguayo SM, Roman J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Practical Approach for Diagnosis and Management. Chest. Sept 2000;118:788-94.

- ^ [39]

- ^ [40]

- ^ [41]