Main Building (University of Notre Dame)

| Main Administration Building | |

|---|---|

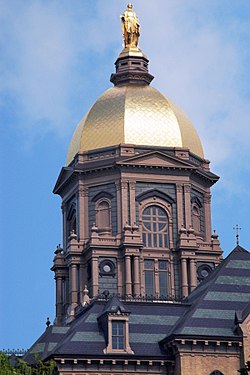

Golden Dome of the Main Administration Building | |

| |

| Alternative names | Main Building, Golden Dome |

| General information | |

| Status | Used as administration and class building |

| Architectural style | Second Empire architecture, Eclectic architecture |

| Town or city | Notre Dame, Indiana |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 41°42′11″N 86°14′20″W / 41.7031°N 86.2389°W |

| Construction started | May 17, 1879 |

| Completed | September 1, 1879 |

| Client | University of Notre Dame |

| Owner | University of Notre Dame |

| Height | 187 feet (57 m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Willoughby J. Edbrooke |

| Website | |

| www.dome.nd.edu | |

Administration Building | |

| Location | Notre Dame, Indiana |

| Coordinates | 41°42′11″N 86°14′20″W / 41.7031°N 86.2389°W |

| Built | 1879[1] |

| Architect | Willoughby J. Edbrooke[1] |

| Architectural style | Second Empire architecture, Eclectic architecture |

| Part of | University of Notre Dame: Main and South Quadrangles (ID78000053) |

| Added to NRHP | May 23, 1978 |

University of Notre Dame's Main Administration Building (known as the Main Building or the "Golden Dome") houses various administrative offices, including the office of the President.[2] Atop of the building stands the Golden Dome, the most recognizable landmark of the university.[3][4] Three buildings were built at the site; the first was built in 1843 and replaced with a larger one in 1865, which burned down in 1879, after which the third and current building was erected. The building hosts the administrative offices of the university, as well as classrooms, art collections, and exhibition spaces. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[5]

History[edit]

First main building[edit]

Edward Sorin, founder of the University of Notre Dame, started construction of the first main building August 28, 1843.[6] The architect was Mr. Marsile of Vincennes Indiana who arrived on campus on the 24th. The structure, which was complete by the fall of 1844,[6] was a brick building eighty feet long by thirty-six feet wide, 4 1/2-story high with a small cupola (but not yet a dome) with a bell in it, in French style.[6] The ground floor had a refectory, kitchen, recreation room, and washing rooms; the second floor had classrooms, study halls, art gallery, and Sorin's office; the third floor had student dormitories, residences for priests and brothers; the fourth floor had dormitories, a museum, and an armory. Two lateral wings (which gave the building the shape of an H) were opened in 1853.[7] It also briefly hosted the office of the infirmarian, Sister Mar of Providence, before a standalone infirmary was built east of the building in 1845.[8]

Second Main Building[edit]

Construction of the second Main Building, which replaced the first, began in 1864 and was completed in 1865 with a cost of $35,500 equivalent to $707,000 in 2023.[9][page needed] The building's construction incorporated a major part of the previous building; its roof was removed and several floors were added along with a large mansard roof, and the facade and porch were altered.[10][page needed] It was 160 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 90 feet high; it was six stories high and had a dome at the top.[11] The dome was made of wood and covered in tin, and it was surmounted by a twelve feet tall, 1800 pounds wooden statue of Mary sculpted by Anthony Buscher of Chicago. Both the dome and the statue were painted white. The octagonal oratory under the dome hosted a $1500 solid gold crown made in France (which today is kept in the Main Building on display).[12] The architect was William Thomas from Chicago, and most of the workers who built it were brothers of the Congregation of Holy Cross.[9] In a publicity stunt to give visibility to the college, Rev. Edward Sorin invited important clerics (including top-ranking American catholic cleric Bishop Martin John Spalding) and congressmen to the dedication on May 31, 1886.[10] Classes were taught on the third floor which hosted thirteen large classrooms and professor rooms, the fourth and fifth floors hosted dormitories, while the refectory and study halls were situated on the first floor.[11] The interior was decorated with 52 stands of medieval armor and a natural history museum, while the exterior featured a Cour d'honneur courtyard and a statue of Sacred Heart by Robert Cassiani, placed in 1893 and modeled after a similar one at Sacré-Cœur in Paris.[10]

Fire of 1879[edit]

The building stood for 14 years before being destroyed by a great fire on April 23, 1879.[5] At around eleven in the morning on Wednesday, 23 April 1879, smoke and flames could be seen rising from the roof of the Main Building.[13] The causes of the fire might be due to repairs on the roof, and the fire might have started due to the dry timber on the roof, although it was not possible to ascertain it.[14] The fire was first spotted from the minim's courtyard, and soon early attempts at putting out the fire were made, with lines of people passing buckets of water towards the roof of the building by steam pressure.[9] Despite these efforts, the fire had spread to the entire roof and quickly consumed the upper floors. The South Bend Fire Department was not able to arrive in time to save the main building, because of the long time needed to round up the volunteer firemen and set up the machines. The supports of the dome burned away and the statue went crashing below in a billow of sparks and flame, and efforts focused on rescuing whatever valuable effects might be carried out of the burning building.[13] In the zeal to save precious objects students threw many of the valuables from the windows, yet despite the well-intentioned effort, almost all of these were lost in crashing on the ground. This was especially true for many of the precious books and manuscripts.[14]

The fire consumed the building in three hours.[15] The building contained most of the school's educational and administrative activities, refectories, and student and faculty living quarters. The flames also consumed The Saint Francis Old Men's Home, the Infirmary, the Minims Hall (the grade school program), and the Music Hall. The fire fighters from South Bend arrived in time help save the kitchen, steam house, printing office, Presbytery, Washington Hall and Sacred Heart Church.[14] Additionally, the lack of strong winds prevented the fire from spreading to these other buildings. Many students, nuns and faculty narrowly escaped serious injury or death while they tried to save the Main Building's contents as parts of the structure came tumbling down around them.[14][16] Most of the university library, the scientific equipment, the paintings and sculptures that adorned the hallways, the furnishings and furniture, students' clothes and possessions, natural and skeletal collections were lost in the fire. The loss was estimated at $200,000 and only $45,000 was recovered from the insurance.[citation needed]

At three o'clock Father William Corby, the university president, met with his wisest assistants and they determined that nothing could be done but close the college for the year.[14] An hour after he communicated the decision to the students assembled in the church. Students did not want to leave, but Fr. Corby made it clear that the university could not provide any accommodations, hence the students were sent home for the semester.[9] An early graduation ceremony was held for the seniors of all schools.[10] Corby also promised that "a new Notre Dame" would reopen in the fall with a new Main Building "more accommodating and grandiose".[10] Condolences started to pour into the school immediately, many of them published in subsequent issues of the student weekly magazine Scholastic.[14]

Father Edward Sorin, now the superior-general of the Congregation of Holy Cross, had left on a trip to Europe two days prior to the fire. He immediately returned to campus after the fire to find much of his school in ruins. Together with Corby, he vowed to the students and faculty to rebuild the school in time for the fall semester.[17] During the next Sunday's Mass, Rev. Sorin delivered the homily and said "If it were all gone, I should not give up!", which electrified the crowd and provided morale for the reconstruction.[10] He wrote to the members of the congregation: "By all means we must bring upon these new foundations the richest blessings of Heaven, that the grand edifice we contemplate erecting may remain for ages to come a monument to Catholicism, and a stronghold which no destructive element can ever shake on its basis or bring down again from its majestic stand".[17]

Current building[edit]

University founder Rev. Edward Sorin and the president at the time Rev. William Corby immediately planned for the rebuilding of the structure that had housed virtually the entire University.[9] Donations for the rebuilding of the college came from the Congregation, alumni, people of Saint Mary's College, South Bend, and Chicago (where Notre Dame students had staged a benefit concert after the Chicago Fire of 1871).[16] General William Tecumseh Sherman, whose sons had attended Notre Dame, sent army tents and supplies for the emergency and Chicago mayor Carter Harrison Sr. presided over a fund-raising to benefit the new building.[10] Maurice Francis Egan published his book Prelude: An Elegent Volume of Poems and donated the royalties to the building fund. The entire University administration and community engaged in fund raising throughout the summer of 1879 to replace the Main Building.

The university took action by selecting, out of 30 competitors, a new design by Willoughby J. Edbrooke, who drew the new plans by May 10.[5] Architect Edbrooke, Brother Charles Borromeo (Patrick) Harding, C.S.C, and mathematics professor William Ivers marked off the dimensions of the construction on the day of the groundbreaking ceremony, May 17, and the first stone for the foundation was laid on the 19th.[10] Railcars full of bricks arrived continuously to town and were brought to campus in a steady stream of wagons. By May 31, twenty-six stonemasons and bricklayers were working with their support crews on the walls of the new building. The construction required about 300 veteran tradesmen, including 156 skilled stonemasons and bricklayers.[9] This exceeded the number of experienced workers in the South Bend area, and was also scarce in Chicago because of the rebuilding effort due to the great fire in October 1871. Hence, skilled workmen were brought into South Bend from great distances.[9]

The construction was very rapid due to the zeal of workers and volunteers.[13] By June 21, the first story was completed, and by June 28, they completed the second. The Fourth of July saw the completion of the third. The building was completed before the fall semester of 1879. Fifty-six bricklayers and 4.35 million bricks were necessary to complete it, and once finished it stood 187 feet tall. The building also required 300 tons of cut limestone.[18] The halls were wide and it was considered hygienic, since they had installed a ventilating system unequalled in any public building in America at the time.[15]

The Golden Dome was the last thing to be finished, with the iron framework, the panels and the columns supporting the dome, being added during the summer of 1882 and the dome itself was finished in September. The statue of Mary atop the dome weighs 4,000 pounds and stands 19 feet tall. It was a gift from the sisters, students, and alumnae of adjacent Saint Mary's College, Notre Dame's sister school.[19] It replicates the pose of the statue of Mary on the Column of the Immaculate Conception in Piazza di Spagna in Rome, erected under Pius IX. It was designed by Chicago artist Giovanni Meli.[20] The statue arrived on campus in July 1880 to replace the one that was destroyed in the fire. The cast-iron statue sat on the rebuilt front porch of the new Main Building for two years while the new dome was completed. The $1 million rebuilding project had left the university in debt. University founder Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., wanted to gild the dome in real gold, but the Holy Cross community's Council of Administration for Notre Dame deemed it too great an extravagance. The standoff lasted into 1886, when Father Sorin used his position as superior general of the community to name himself to the committee and asked to be its chairman. He then refused to come to the meetings so that the other members could not legally conduct its business, even moving to temporary quarters at Saint Mary's and refusing to return. When University business halted, the committee relented and Father Sorin got his Golden Dome and statue.[21] The first project cost $2,000, while the 10th gilding of the dome in 2005 cost $300,000.[21]

By the mid-1880s, two lateral wings were added to each building to serve as dormitories, Carroll Hall on the west and Brownson Hall to the east, bringing the length of the building from 224 feet to 320.[22]

Brownson and Carroll Halls were closed by 1945 and the space was converted into offices.[23]

Architecture[edit]

The building's style has been described as follows:

Edbrooke called the finished product ‘modern Gothic’; a later University Architect, Francis Kervick, referred to the Victorian monument as 'an eclectic and somewhat naïve combination of pointed windows, medieval moldings and classical columns.' Others have dubbed the buildings’ riot of turrets, gables, angles, corners, and oversized dome and rotunda as pure and simple 'modern Sorin'.[15]

Interior[edit]

The halls are decorated by portraits of the presidents of the university. The lower level hosts a gallery dedicated to the Laetare Medal awardees and the Wall of Honor adorned by plaques dedicated to notable people awarded for their service to the university.[2] The building also houses the Columbus murals, a group of large paintings by Italian painter and Notre Dame professor Luigi Gregori, depicting the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus.[3] Gregori also painted with figures representing Religion, Philosophy, Science, History, Fame, Poetry and Music.[3][24]

Usage and traditions[edit]

The building is the location of many administrative offices of the university, including that of the president, Office of Admissions, and various other offices and services of the university. Additionally, it has classrooms and meeting rooms.[2]

In campus lore, if a student ascended the front steps of the Main Building before graduation, that student was doomed never to graduate.[3] This legend stems from traditionalist smoking rituals. Students were not deemed worthy to climb the steps and smoke with their professors until they received their degrees and were educational equals.[10]

Main building is also used as the venue for "Dome Dances," which are dances awarded to residence halls who have been given the title of Hall of the Year. These dances take place on the second floor of main building, underneath the dome itself which makes them a coveted event for students to attend.[24]

Gallery[edit]

-

Main building seen from Main Quad

-

The Main Building in winter

-

The Dome seen from Cavanaugh Hall

-

Close up of the Golden Dome

-

Golden Dome at night

-

Close up of the Statue of Mary

-

Interior of the Golden Dome

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Official Building Inventory" (PDF). Facilities Design and Operations. University of Notre Dame. October 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Main Building — Virtual Tour — Sights and Sounds — Campus and Community". University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Romancing the Golden Dome". tribunedigital-chicagotribune. September 26, 2004.

- ^ Dame, Marketing Communications: Web // University of Notre (March 3, 2005). "Golden Dome to be regilded for the tenth time". Notre Dame News.

- ^ a b c James T. Burtchaell (November 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: University of Notre Dame Campus-Main and South Quadrangles" (PDF). Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database and National Park Service. Retrieved October 18, 2017. With seven photos from 1972 to 1976. Map of district included with version available at National Park Service.

- ^ a b c Sorin, Edward (1992). The Chronicles of Notre Dame Du Lac. Notre Dame Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-268-02270-9.[page needed]

- ^ Blantz, Thomas E. (2020). The University of Notre Dame : a history. [Notre Dame, Indiana]. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-268-10824-3. OCLC 1182853710.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Blantz, Thomas E. (2020). The University of Notre Dame : a history. [Notre Dame, Indiana]. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-268-10824-3. OCLC 1182853710.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Hope, Arthur J. (1941). Notre Dame: One Hundred Years. University Press. ISBN 978-0896515017.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schlereth, Thomas (1991). A Dome of Learning: The University of Notre Dame's Main Building. University of Notre Dame Alumni Association.[page needed]

- ^ a b A Guide To South Bend, Notre Dame du Lac, and Saint Mary's Indiana. Philadelphia: J. B. Chandler, Printer. 1865.

- ^ Archives, Notre Dame (May 31, 2013). "Consecration of Notre Dame". Notre Dame Archives News & Notes. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Day We Commemorate" (PDF). Notre Dame Scholastic. 14: 500–505. April 1881.

- ^ a b c d e f "Our Great Calamity" (PDF). Notre Dame Scholastic. 12: 533–534. April 1879.

- ^ a b c Schlereth, Thomas (1976). The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History and Campus. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 55–9.

- ^ a b "The Old College" (PDF). Notre Dame Scholastic. 12: 538–545. May 1879.

- ^ a b "Circular Letter No. 96 from Fr. Sorin to the Holy Cross Community" (PDF). archives.nd.edu. May 23, 1879.

- ^ "Notre Dame: Main Building". Archives.nd.edu. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Notre Dame -- 100 Years: Chapter XIII". Archives.nd.edu. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "The statue and the Dome // Notre Dame 175 // University of Notre Dame". 175.nd.edu. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ BLANTZ, THOMAS E. (August 31, 2020). The University of Notre Dame. University of Notre Dame Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv19m61kd. ISBN 978-0-268-10824-3.

- ^ "Notre Dame Alumnus" (PDF). Archives.nd.edu. June 1945. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "Administration Building, University of Notre Dame". Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

External links[edit]

- Notre Dame One hundred years

- Campus Tour

- Notre Dame Archives

- Live Webcam

- Article in the Chicago Tribune

- Article on ESPN

- "WNDU Vault: Terry McFadden explores The Golden Dome at Notre Dame" on YouTube (channel WNDU 16 News Now, February 24, 2024 [n.d.])

- University of Notre Dame buildings and structures

- University and college buildings completed in 1879

- National Register of Historic Places in St. Joseph County, Indiana

- Historic district contributing properties in Indiana

- University and college administration buildings in the United States

- Second Empire architecture in Indiana

- Domes