ManKind Project

| |

| Founded | 1984, Wisconsin, United States |

|---|---|

| Founder | Rich Tosi,[1] Bill Kauth[2] Ron Hering |

| Type | Not For Profit |

| Focus | Men's movement |

| Product | Personal development |

Key people | Board Chair: Darryl Hansome; Chair-Elect: Lonnie Hamilton[3] |

| Website | mankindproject |

ManKind Project (MKP) is a global network of nonprofit organizations focused on modern male initiation, self-awareness, and personal growth.[4][5]

Scope[edit]

The ManKind Project has 12 regions: Australia, Belgium, Canada, French Speaking Europe, Germany, Mexico, New Zealand, Nordic (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland), South Africa, Switzerland, The United Kingdom and Ireland, and 22 Areas in the United States. There are also three developing regions: Israel, The Netherlands, and Spain.[6]

History[edit]

MKP has its origins in the mythopoetic men's movement of the early 1980s, drawing heavily on the works of Robert Bly, Robert L. Moore, and Douglas Gillette. In 1984, Rich Tosi, a former Marine Corps officer; Bill Kauth, a social worker, therapist, and author; and university professor Ron Hering, Ph.D. (Curriculum Studies); created an experiential weekend for men called the "Wildman Weekend" (later renamed "The New Warrior Training"[7]). As the popularity of the training grew, they formed a New Warrior Network organization, which would later become The Mankind Project.[2][8]

New Warrior Training Adventure[edit]

MKP states:

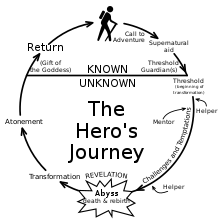

The New Warrior Training Adventure is a modern male initiation and self-examination. [...] It is the "hero's journey" of classical literature and myth that has nearly disappeared in modern culture.[9]

MKP states that those who undertake this journey pass through three phases characteristic to virtually all historic forms of male initiation: descent, ordeal and return.[10] Participants surrender all electronic devices (cell phones, watches, laptops, etc.), weapons (guns, knives, etc.) and jewelry for the weekend. This was explained as way of removing the "noise of a man's life", separating the man "from what he is comfortable with,"[11] and ensuring the safety of all participants.[12]

Participants agree to confidentiality of the NWTA processes, to create an experience "uncluttered by expectation" for the next man and to protect the privacy of all participants. MKP encourages participants to freely discuss what they learned about themselves with anyone.

Training courses usually involve 20 to 32 participants, and some 30 to 45 staff.[13] The course usually takes place at a retreat center, over a 48-hour period, with a one-to-one ratio of staff to participants.[11]

Research[edit]

Researchers reported on data from 100 men, whom they interviewed and administered a battery of questionnaires, before the men participated in a New Warrior Training Adventure during 1997-1999. The same men completed a set of follow-up questionnaires 18 months after they had completed the NWTA. The men endorsed changes such as "... [becoming more] assertive and clear with others about what I want or need" and "... accept[ing] total responsibility for all aspects of my life".[14] The study findings also indicated that the men had more social support and experienced more life satisfaction 18 months after the NWTA.

The authors acknowledge limitations to their research, since they did not have a comparison or control group, which results in various "threats to internal validity"[15] mentioned by the researchers, primarily history, maturation, and selection bias.

A second study accumulated data from 45 trainings held between 2006-2009, indicated that the psychological well-being of participants, as well as other indicators, improved after the initial weekend of participation in an NWTA. Many of the initial changes endured across a 2-year follow-up period.[16]

Integration Groups (I-Groups)[edit]

MKP co-founder Bill Kauth's 1992 book A Circle of Men: The Original Manual for Men's Support Groups details how groups of men can assemble to help one another emotionally and psychologically.[17] Men who have completed the NWTA are encouraged to consider joining such a group. An optional "Integration Group" training is offered shortly after each NWTA; a fee is charged for this training (fees vary by community and format). Some training courses are part of a small integration group on their own with qualified leaders, other training courses take place over an entire weekend and can cost between $100 and $250 depending on lodging, location, and number of men attending.

The "I-Group" is for participants to engage in ongoing personal work and to apply the principles learned on the NWTA to their lives. I-Groups are available to all men who complete the NWTA, and sometimes to men who want to explore the Mankind Project. Many I-Groups meet one evening per week. A typical I-Group meeting includes conversation and sharing in a series of "rounds" that allow each man to be heard.[18]

In both the New Warrior weekend and the follow-up groups, Mankind Project "... focuses on men's emotional well-being, drawing on elements like Carl Jung's theories of the psyche, nonviolent communication, breath work, Native American customs, and good old-fashioned male bonding".[19]

A study conducted in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area collected retrospective survey data from members of 45 I-groups that met between 1990 and 1998. At the end of the study period (1998), 23 groups were active and 22 had disbanded. Groups were active for 4.5 years (median), and the median length of individual participation was 26.2 months (2.2 years).[a] Each group consisted of about six men. Survey participants rated their groups as moderately effective.[20]

Other training courses[edit]

MKP is affiliated with several similar training programs:

- Becoming a Man (BAM) - a program in Chicago for inner-city adolescent boys[21][22]

- Boys to Men, for adolescent boys[5]

- Inner King, for "initiating men into sovereign, kingly energy"[2]

- Inside Circle, for convicts in maximum security prisons[23]

- Underground Railroad Training Odyssey,[24] sponsored by the Inward Journey African American Council[25]

- Vets Journey Home (formerly "Bamboo Bridge"), for combat veterans[26]

- Warrior Monk, for "men and women who are in a transition phase of life"[2]

- Woman Within International, for women[27]

Public figures[edit]

My Morning Jacket frontman (vocals, guitar) Jim James, told Pitchfork magazine:[28]

There's this group called ManKind Project, they lead retreats to try and help men feel more OK with all the different sides of being a man. I went on one of those retreats because I was so intrigued. It was fucking amazing. The experience was about taking accountability for yourself and your actions ...

Actor Wentworth Miller, in an address to the Human Rights Campaign during an event in 2013, describes his involvement with MKP as vital to his coming out process, and his introduction to being part of an accepting community.[29] In his letter rejecting an invitation to the Festival of Festivals, Saint Petersburg on grounds that he as a gay man could not support the event while Russian law prohibits homosexuality, Miller signed as a member of the ManKind Project as well as member of the HRC and GLAAD.[30]

Actor Eka Darville told the New York Times that MKP helped him become a better father, commenting, "There is no way I could have done that without a brotherhood telling me all the bull I was projecting onto my wife . ... "[19]

Frederick Marx, a film director, writer, and producer (Hoop Dreams, Journey from Zanskar) talks openly about his involvement with MKP,[31] and has made documentary films involving the organization, e.g., The Tatanka Alliance[32] about a "Hunka" ceremony[33] to consecrate an alliance between the ManKind Project USA and the Pine Ridge Oglala Lakota elders community.

Criticism[edit]

A 2007 Houston Press article[34] detailed criticisms of the ManKind Project. Anthropology associate professor Norris G. Lang[35] said that some of the groups' exercises that he attended were "fairly traumatic" and were "dangerous territory for an unprofessional"; and Anti-cult advocate Rick Alan Ross said that The ManKind Project appears to use coercive mind-control tactics, such as limiting participants' sleep and diet, cutting them off from the outside world, forcing members to keep secrets, and using intimidation.[34] A response by the ManKind Project states: "If you have visited the [Cult Education Forum],[b] you know he refers to the ManKind Project as a large group awareness training ... Rick Ross doesn’t call us a cult."[36]

Wrongful death lawsuit[edit]

A 2007 wrongful death lawsuit filed by the parents of Texan Michael Scinto charged that MKP was responsible for his suicide.[34] The parents said that he had struggled with alcohol and cocaine addiction in the past. Scinto was a 29-year-old adult who had been sober for a year and a half prior to his attending MKP's New Warrior Training Adventure in July 2005. Two days after Scinto returned from the NWTA retreat, he sought psychiatric help at Ben Taub Hospital. He subsequently resumed drinking and taking drugs, and he then committed suicide.[34] The parties settled in 2008. The terms of the settlement were not publicly disclosed, although a copy of the court documents were posted online by Warren Throckmorton,[37] and aspects of the settlement were reported in the press.[38][39]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Based on survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method.

- ^ The Mankind Project calls it the "Rick Ross Cult Forum."

References[edit]

- ^ "About the Presenters". www.tosi.biz. Tosi and Associates. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

In 1985, Rich co-founded the ManKind Project ...

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d Baer, Reid (May 2006). "May interview with Bill Kauth". A Man Overboard. MenStuff: The National Men's Resource. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

Bill Kauth is a co-founder of the New Warrior Training Adventure of the ManKind Project ...

- ^ "MKP USA Board of Directors". ManKind Project USA. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "The ManKind Project of Chicago". chicago.mkp.org. ManKind Project of Chicago. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ a b "www.mankindproject.org". www.mankinkproject.org. Mankind Project. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- ^ "ManKind Project Global Regions". ManKind Project. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "MKP website". Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ "Interview with Bill Kauth". www.menweb.org. M.E.N. Magazine. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "New Warrior Training Adventure". chicago.mkp.org. The ManKind Project of Chicago. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- ^ Gary, Stamper (2012). Awakening the new masculine: the path of the integral warrior. Bloomington, IN. p. 4. ISBN 9781469731506. OCLC 779879021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Barry, Chris (2003-10-23). "Male transformer: Mankind Project uses mysterious rituals to help heal wounded men". Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Montreal Mirror. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ "The New Warrior Training Adventure". ManKind Project. Retrieved Apr 30, 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about the New Warrior Training Adventure". www.mkp.org. Mankind Project. Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ Burke, Christopher K.; Maton, Kenneth I.; Mankowski, Eric S.; Anderson, Clinton (2010). "Healing Men and Community: Predictors of Outcome in a Men's Initiatory and Support Organization". American Journal of Community Psychology. 45 (1–2): 186–200. doi:10.1007/s10464-009-9283-3. PMID 20094770. S2CID 503513.

- ^ Shadish, William R.; Cook, Thomas D.; Campbell, Donald T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 108, 139. ISBN 9780395615560. OCLC 804092255.

- ^ Maton, Kenneth I.; Mankowski, Eric S.; Anderson, Clinton W.; Barton, Edward R.; Karp, David R.; Ratjen, Björn (2014-01-01). "Long-Term Changes among Participants in a Men's Mutual-Help Organization" (PDF). International Journal of Self Help and Self Care. 8 (1): 85–112. doi:10.2190/sh.8.1.j. ISSN 1091-2851.

- ^ Kauth, Bill (1992). A Circle of Men: The Original Manual for Men's Support Groups. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-07247-3. OCLC 24871074.

- ^ Jackman, Michael (2006-11-29). "Band of brothers: The men's movement (still) want guys to open their hearts". Metro Times. Scranton, Pennsylvania: Times-Shamrock Communications. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ a b Seligson, Hannah (December 8, 2018). "These Men Are Waiting to Share Some Feelings With You". New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Mankowski, Eric S.; Maton, Kenneth I.; Burke, Christopher K.; Stephan, Sharon Hoover (2014). "Group Formation, Participant Retention, and Group Disbandment in a Men's Mutual Help Organization" (PDF). International Journal of Self Help and Self Care. 8 (1): 41–60. doi:10.2190/sh.8.1.h.

- ^ "Becoming a Man". urbanlabs.uchicago.edu. University of Chicago, Urban Labs. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

In two randomized controlled trials, the Crime Lab found that BAM cuts violent-crime arrests among youth in half and boosts the high school graduation rates of participants by nearly 20 percent.

- ^ Trickey, Erick (September 21, 2017). "Group Therapy Is Saving Lives in Chicago". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

BAM also requires all counselors to go on a weekend retreat put on by the ManKind Project, a Chicago-based organization that dates back to the men's movement of the 1980s and 1990s. The retreat is a key part of BAM counselors' "rites-of-passage work," an ongoing examination of their challenges and character. Men who won't make themselves vulnerable, Di Vittorio says, won't inspire boys to do the same.

- ^ "Missions of Service". www.mkp.org. Mankind Project. Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ "The Underground Railroad Odyssey Training". www.inwardjourney.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Who We Are". www.inwardjourney.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Welcome to Vets Journey". www.vetsjourneyhome.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Home Page - Woman Within International". womanwithin.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Jim James". Pitchfork magazine.

- ^ "Video: Wentworth Miller Talks About Coming Out, Overcoming Struggles at HRC Dinner | Human Rights Campaign". www.hrc.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-15.

- ^ "Wentworth Miller rejects Russian film festival invitation; 'As a gay man, I must decline'". GLAAD. Aug 21, 2013. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved Apr 30, 2020.

- ^ "Frederick Marx". ManKind Project. 2018-07-25. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- ^ "The Tatanka Alliance". Warrior Films. 19 September 2015. Retrieved 2019-02-26.

- ^ Walker, James R. (1917). The Sun Dance and Other Ceremonies of the Oglala Division of the Teton Dakota. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 16. New York: The Trustees of the American Museum of Natural History. p. 122. OCLC 28842775.

The relationship of Hunka is difficult to define, for it is neither of the nature of a brotherhood, nor of kindred. It binds each to his Hunka by ties of fidelity stronger than friendship, brotherhood, or family.

- ^ a b c d Vogel, Chris (2007-10-04). "Naked Men: The ManKind Project and Michael Scinto". Houston Press. Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ "Norris G. Lang". www.uh.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". ManKind Project. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ Certified Document Number 37853765 (20 pages), certification signed by Theresa Chang, District Clerk, Harris County, Texas (June 3, 2008), containing three documents: Defendants' Motion to Enforce Settlement Agreement (May 20, 2008) (pp. 1–4); Settlement Agreement (Exhibit A, April 10, 2008) (pp. 5–9); and Full and Final Release and Settlement Agreement (Exhibit B, undated) (pp. 10–20); Harris County, Texas, District Court, 333rd Judicial District, Cause No. 2007-43994; https://www.wthrockmorton.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/nwtascinto.pdf

- ^ Vogel, Chris (June 25, 2008). "A New Retreat for the ManKind Project Houston". Houston Press. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Villarreal, Daniel (September 14, 2012). "Controversial ManKind Project reaches out to gay community". Dallas Voice. Retrieved December 11, 2018.