Maratha–Nizam wars

| Maratha–Nizam wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mughal–Maratha Wars, Anglo-Maratha wars, and Anglo-Mysore wars | |||||||||

Map of India in 1765 (left) and 1805 (right). | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

The Maratha-Nizam wars (1720–1819) was a series of military conflicts between the Maratha Empire and the Nizam of Hyderabad, spanning nearly a century. These conflicts arose primarily from the Marathas' imposition of Chauth, a form of tribute, on the Nizam's dominions, leading to tensions and subsequent hostilities between the two powers. The Nizam's response to the Maratha demands sparked a series of clashes and wars aimed at resisting Maratha encroachment and asserting territorial sovereignty.

Nizamul Mulk Asaf Jah I, a Mughal noble since the reign of Aurangzeb, played a significant role in Deccan's political landscape, engaging in multiple conflicts with the Marathas. His actions included aiding the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah by deposing the Sayyid Brothers. Following this, Nizamul Mulk established his dynasty in Deccan, known as the Asaf Jahi dynasty, after securing victory in the Battle of Shakarkheda. However, tensions arose with the Marathas, neighbouring rulers of the Deccan, who held the right to collect Chauth as promised by the Sayyid Brothers. This conflict initiated the early Nizam-Maratha conflicts, with the Maratha Chatrapatis and Peshwas launching several military campaigns against the Nizam throughout the 18th century.

The Deccan region witnessed a series of significant events during the 18th and 19th centuries, including conflicts surrounding the succession of Asaf Jah I, which involved his sons Nasir Jung, Salabat Jung, and Muzaffar Jung, and the subsequent rule of Asaf Jah II as the Nizam. Concurrently, following the passing of the first Peshwa, Bajirao I, his son Balaji Bajirao ascended to the position of Peshwa. Balaji continued his father's legacy by leading numerous campaigns against the Nizam. Upon Balaji's demise, Madhavrao I succeeded him as Peshwa, despite facing pressure from his uncle Raghunathrao. Madhavrao proved to be a capable leader, leading successful campaigns against the Nizam. Later, an alliance was formed between the Nizam and the Peshwa to confront the Marathas of Nagpur, resulting in the capture of territories from them. The alliance between the Marathas and the Nizam endured until the downfall of Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Following this, Nizam Asaf Jah II signed a treaty with the British, becoming a subsidiary ally of the British Empire, at the behest of Arthur Wellesley.

The third Anglo-Maratha war signalled the conclusion of hostilities between the Maratha Empire and the Nizam. In this conflict, the combined forces of the British and the Nizam captured Nagpur, compelled the surrender of the Peshwa Bajirao II and effectively ended the Maratha Empire. Following these events, the Nizam was declared as the successors of the Peshwa and was relieved from paying Chauth to the Marathas. Additionally, territories such as Vaizapur and Kannad from the Peshwa, as well as Ellora and Aurangabad from Holkar, were annexed to the Nizam's dominions. These conflicts between the Marathas and the Nizam left a significant imprint on the military history of the Deccan during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Overview[edit]

Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, who served as the Subahdar of the Deccan Subah within the Mughal Empire, founded his independent kingdom in the Deccan, recognized as the Asaf Jahi dynasty.[1] Despite this, the Nizam maintained loyalty to the Mughals and continued to acknowledge their suzerainty.[2] He gained effective control over the Deccan, establishing his authority as the overlord of all six Mughal viceregal governorates in the region.[1]

The Maratha Empire emerged as a powerful force in the Deccan during Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah's rise to power. In the Battle of Shakar Kheda, where Nizam secured victory over the Mughals, he received support from the Marathas. Nizam acquired independence from the Mughals right after the victory.[3]

History[edit]

For the Mughal empire[edit]

In 1691, Mir Qamaruddin, later titled Nizam-ul-Mulk, was bestowed with the honorific Chin Qilich Khan and received an elephant as a gift.[4] The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb entrusted him with the leadership of the Turani regiment from Ghaziuddin Khan, the father of Qamaruddin Khan.[5]

Battle at Karad (1693)[edit]

In 1693, during the Mughal siege of the Panhala fort, a substantial Maratha force surrounded the Mughal army. Upon learning of this situation, Emperor Aurangzeb dispatched Ghaziuddin Khan and Khanzada Khan. As the Marathas, led by Dhana Jadav, retreated towards Satara, Firuz Jung sent Qilich Khan(Nizam) and Rustam Khan in pursuit. A decisive battle ensued near Karad, resulting in the defeat of the Marathas. Thirty Maratha soldiers were captured, and 600 horses were seized by the Mughals.[6]

Capture of Parali Fort (1700)[edit]

In 1700, Mughals led by Fethullah Khan initiated a siege on Parali fort to capture it. The fort was under the charge of Parashuram Trimbak, positioned on a high hill, the fort's defence required strategic measures.[7] Chin Qilich Khan received orders to encircle nearby villages, preventing Maratha interference that could sever Mughal supply lines. The fort fell to the Mughals on June 9, 1700.[8]

In recognition of his contributions, the Emperor bestowed upon Chin Qilich Khan the significant role of faujdar of Bijapur Carnatic. Additionally, he was granted an increase of 400 horses, elevating his rank to 4,000 zat and 3,600 horses.[9][10]

Siege of Wagingera (1704)[edit]

The Siege of Wagingera in 1704-5 marked a Mughal military campaign against the Maratha stronghold of Berar, focusing on the Wagingera fort, under Pema Naik. Chin Qilich Khan and Tarbiyat Khan were entrusted with the leadership of this campaign.[11]

In 1705, Aurangzeb personally led the effort to conquer the fort.[11] The Mughals defeated Pema Naik, and successfully captured the fort from the Marathas.[12] Chin Qilich Khan significantly contributed to the capture of Wagingera, a stronghold of the rebellious Berads. Recognizing his capabilities and services, he was promoted to the rank of 5000 zat and 5000 sawar. Following this achievement, Chin Qilich Khan gained considerable influence over the Emperor, being consulted on all crucial state matters.[13]

Because of Chin Qilich Khan's quiet support during the power struggle that led to Farrukhsiyar becoming the emperor, he was given the title Nizam-ul-Mulk. In February 1713, he was also appointed as the Subahdar of the Deccan Subah, a role he held for two years and two months. This fulfilled Nizam-ul-Mulk's ambition when he was a little over 42 years old.[14] Nizam terminated the tax exemptions granted to the Marathas by Daud Khan Panni. This move aimed to gain support from Sambhaji II, a Maratha leader, who opposed the enthronement of Shahu I.[15]

-

Shahu I, who became the Chatrapathi of the Marathas.

-

Idol of Sambhaji II, who opposed the enthronement of Shahu I, and made friendly relations with the Nizam.

Nizam capitalized on the conflict among the Marathas such as Battle of Khed and began reasserting Mughal authority over the Deccan region.[16] Chandrasen Jadhav, Dhana Jadhav's son, sided with Nizam, abandoning Shahu. He sought refuge with Rao Nimbalkar and Sharja Rao Gatghe, who also switched allegiance. With Nizam-ul-Mulk's recommendation, Sharja Rao Gatghe was granted a jagir in Sambhaji of Kolhapur, known as Kagal state. Nizam protected Chandrasen Jadhav, granting him a significant fief with an annual revenue of 25 lakhs for maintaining his troops. Chandrasen Jadhav was required to keep 15,000 well-equipped men, and he was treated as a noble, consulted on important matters concerning the Marathas.[17]

Conflict regarding tax collection[edit]

Nizam directed his troops towards Godavari to compel Shahu's officers, who were causing havoc in the countryside. In the ensuing encounter, the Marathas were pushed back towards the Bhima River. In response to this setback, Shahu sent Balaji Vishwanath against Nizam's forces. A significant battle occurred near Purandar, resulting in a severe defeat for the Marathas, compelling them to withdraw to the Ghats. The Mughal contingent under Nimbalkar took control of the vacated territories near Pune. In recognition of his service, Nizam granted these territories to Jadhav. Following this, a treaty was signed between Nizam and Balaji Vishwanath, though the exact terms remain unknown, presumably involving the mutual release of captives and prisoners.[18]

Rebellion aganist Nizam (1714)[edit]

In 1714, a rebellion aimed at toppling Nizam-ul-Mulk's government unfolded. Secret Maratha agents orchestrated conspiracies to undermine Mughal control in Deccan. A Deshmukh named Anbuji assembled 10,000 men at a fortress constructed during Daud Khan's rule in Deccan. Upon learning of this, Anwar Khan, a district officer at Phulmari, moved to restore peace in a town sixteen miles northeast of Aurangabad.[19]

Anwar Khan encountered Kalu, a Maratha revenue collector who pretended to have lost his job and sought employment in the Mughal service. Agreeing to accompany them as a guide due to his knowledge of the terrain, it later became apparent to Anwar Khan that Kalu was a Maratha agent sent to mislead him. Kalu was arrested, but not before they neared the rebels' stronghold. The rebels captured Anwar Khan and his troops. Upon learning of this, Nizam dispatched Ibrahim Khan Panni, the brother of Daud Khan Panni with a small army.[19]

Due to continuous heavy rain, Ibrahim Khan's army faced equipment issues with their arrows, bows, and matchlocks. Additionally, the Marathas were greater in number than them and that intensified their pressure during the engagement, forcing Ibrahim Khan's army to retreat. In response, Ibrahim Khan urgently requested reinforcements from Nizam-ul-Mulk. Upon receiving the message, Nizam-ul-Mulk ordered his bodyguard to be sent, led by his eight-year-old elder son, Ghaziu'd-Din Khan. Muhammad Ghiyas Khan and Mirza Beg Khan Bakhshi, seasoned leaders, were appointed as his guardians.[19]

Upon learning of the arrival of Ghaziu’d-Din Khan’s force, the Marathas, fearing the situation, fled and sought refuge in the hilly jungle, concealing themselves. They abandoned all their equipment, horses, and artillery on the battlefield, making no further attempts at resistance. Muhammad Ghiyas Khan instructed some of his officers to pursue the fleeing Marathas and eliminate them. Subsequently, he ordered the complete demolition of the small fortress (garhi) and destroyed several other Maratha strongholds in the vicinity where rebels from the Imperial territory sought shelter. Muhammad Ghiyas Khan's forces pursued the Marathas for 150 miles, driving them into the hills' caverns. They captured two war elephants. Upon their return to Aurangabad, Nizam-ul-Mulk was delighted to hear that the country was resettled, the people reassured, and the enemy subdued.[19]

Nizam, leading a force of six thousand horsemen and five thousand infantry, personally marched to regions where Maratha leaders had caused chaos. He successfully subdued the Marathas at Mungi-Shevgaon, Shahgarh, and Jalna.[19] Two days after these campaigns, Haider Quli Khan was dispatched from Delhi to the Deccan capital (Aurangabad) with a message stating that Mir Jumla was on the verge of assuming the Subahdari title of the Subah.[19]

In May 1715, Nizam-ul-Mulk was summoned back to the court, anticipating the appointment of Husain Ali Khan as the new Viceroy of the Deccan. He promptly departed from Aurangabad to Burhanpur, where he learned about two Maratha chiefs imposing Chauth on the local people. Nizam-ul-Mulk confronted them, chasing them into a dense forest ablaze by the Marathas. Skillfully navigating his army, he pursued the enemy for eighty miles before returning to Burhanpur. There, he appointed Zafar Khan as the Governor of the Subah of Khandesh before continuing his journey to the North.[19]

At Malwa[edit]

Given the governorship of Malwa, Nizam-ul-Mulk became instrumental when the young emperor sought liberation from his Sayyid captors. When the Sayyids attempted an abrupt transfer from Malwa, Nizam marched against Delhi. In his plea for noble support, he lamented the decline of the Timurid house and the monarchy, expressing concern that the Sayyids aimed to undermine all old Irani and Turani families of the empire, following a detrimental pro-Hindu policy. Nizam rallied Irani and Turani commanders who were dismayed by Farrukhsiyar's deposition and slaying, particularly wary of full power going to Indian Muslims, despite their distinguished familial service to the Timurids. This split could be perceived as a division between foreign, cosmopolitan officers and locally rooted cadres consisting of Indian Muslims, Rajputs, Marathas, and Jats.[1]

Battle of Balapur (1720)[edit]

In September 1719, Muhammad Shah ascended the Mughal throne with the Sayyid brothers (Sayyid Hassan Ali andSayyid Abdullah Khan) as regents, influencing the administration for a year. A revolt was orchestrated against the Sayyids, led by Nizam-ul-Mulk, challenging their influence. The Sayyids strategically moved Nizam-ul-Mulk to Malwa earlier from Deccan, aiming to curb his growing power. In 1720, Nizam-ul-Mulk marched towards the Deccan, prompting a conflict with Dilawar Ali Khan and Alam Ali Khan. Both were the commanders of the Sayyid brothers. Nizam secured victories, strategically positioning himself in the power struggle. Shahu dispatched reinforcements to aid the Sayyids, yet they were also defeated by Nizam's forces. The Sayyids, recognizing their vulnerability, sought alliances, but Nizam-ul-Mulk triumphed in a decisive battle at Balapur. Hussain Ali Khan's march from Delhi resulted in his assassination, leading to the Sayyids' defeat in Delhi. Emperor Muhammad Shah, issuing orders to Nizam-ul-Mulk and others, recounted the Sayyid betrayal and instructed them to unite against Sayyid Abdullah Khan.[11]

Following the assassination of Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan, Sayyid Hassan Ali Khan was defeated and killed at the Battle of Hasanpur. This marked the end of the prolonged control of the Sayyid Brothers over the Mughals.[20] Sayyid Hassan Ali Khan, who served as the Grand Vizier of the Mughal Empire, was replaced by Emperor Muhammad Shah, appointing Nizam as the new Grand Vizier.[21]

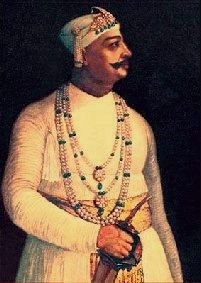

As the Nizam of Hyderabad[edit]

Nizam-ul-Mulk, in his quest to eradicate corruption at the Court, made enemies, particularly among the Emperor's close companions. Their unfavourable words about him to the Emperor wounded his ego. Disheartened by the state of affairs, Nizam-ul-Mulk resigned as grand vizier in 1724, returning to the Deccan to reclaim his previous role as viceroy. However, the position was already held by Mubariz Khan, appointed by Emperor Farrukhsiyar nine years earlier. Nizam-ul-Mulk confronted Mubariz Khan at the Battle of Shakar Kheda, resulting in Mubariz Khan's fatal injury. Nizam-ul-Mulk sent Mubariz Khan's severed head to the Emperor, who responded with gifts, a War Elephant, and the prestigious title of Asaf Jah – the highest honour bestowed by the Mughal king. This title likened the recipient to Asaf, the grand vizier in King Solomon's Court, signifying extraordinary recognition.[21] Bajirao I, the Maratha Peshwa, aided Nizam at Shakar Kheda under Shahu I's orders. In gratitude for his assistance, Nizam rewarded Bajirao with 7,000 Mansabs and 7,000 horses after the victory in the battle.[22]

-

Flag of the Nizam of Hyderabad in 18th century

-

Flag of the Mughal empire

-

Flag of the Maratha empire

Shripatrao Pant, the Pratinidhi of the Maratha empire initially resisted the expansion northward, fearing it would create difficulties for the Marathas and discontent with the emperor and Nizam.[23][24] Parushuram Pant Pratinidhi, a Deshasta Brahmin, served as the primary spokesperson for the Nizam at Shahu's court. He was a direct competitor of Bajirao, a Chitpavan Brahmin, within the inner circle. Conversely, Chandrasen Yadav, as a significant supporter of the Nizam, played a crucial role at Tarabai's court, having previously engaged in battle with Bajirao's father a decade earlier. However, Bajirao persuaded Shahu that this "arbitration" was a guise for the Nizam to assume control of the Maratha polity by supporting Tarabai's line.[25]

Campaigns in Carnatic (1725-27)[edit]

In a bid to consolidate power, the Nizam ordered the deployment of an army led by Iwaz Khan, the Prime Minister of the Nizam, to the Carnatic region in 1725. The objective was to suppress Maratha revenue collections in that area.[26] Iwaz Khan laid siege to Trichinopoly and successfully captured it from Serfoji I, the ruler of the Tanjaore Maratha Kingdom. In response to Serfoji's plea for assistance, Shahu dispatched Fateh Singh Bhonsale and Bajirao with a force of 50,000, but they were defeated and compelled to retreat. Two years later, Shahu, with the backing of Tulaji, once again sent Bhonsale, but the Nizam's army emerged victorious, leading to the expulsion of Maratha tax collectors from the Carnatic region.[27] Recognizing the threat posed by the proximity of his capital Aurangabad to Maratha dominions, the Nizam decided to relocate his capital, choosing Hyderabad as the new seat of power.[28]

Battle of Palkhed (1727)[edit]

In November 1727, the Nizam, accompanied by Sambhaji II, advanced towards Pune, the Maratha capital, facing no resistance upon entry. Nizam appointed Sambhaji II as the Chhatrapati (King) of the Marathas. In response, Bajirao marched from the south, pillaging Aurangabad and Burhanpur. Learning of this, Nizam evacuated Pune and headed back to his territory. The two forces clashed at Palkhed on 25 February 1728 in a fierce yet inconclusive battle. Following the engagement, Bajirao besieged Nizam, cutting off his supplies, leading to the signing of the 'Treaty of Mungi-Shevgaon' on 6 March 1728. While Bajirao demanded the surrender of Sambhaji II, Nizam refused, and the treaty resulted in Nizam withdrawing support for Sambhaji II and acknowledging Shahu I as the rightful ruler of the Marathas.[24]

Nizam's march towards Delhi (1737)[edit]

In 1737, as part of the Maratha campaigns in Awadh, Bajirao conducted a raid on Delhi. In response, Emperor Muhammad Shah called upon the Nizam to come to Delhi and directed him to proceed to Malwa, aiming to liberate it from the influence of the Marathas.[29] Upon learning of Nizam's march, Bajirao dispatched Maratha Zamindars to impede his progress. The Nizam's forces, led by Sayyid Jamal Khan, the son of Iwaz Khan, engaged the Maratha leader Goriyya with 1,000 horses and 1,500 foot soldiers. The Nizam's forces emerged victorious, defeating Goriyya and compelling him to retreat. Consequently, Nizam continued his march towards Delhi, reaching the city on 12 July 1737.[30]

Battle of Bhopal (1737)[edit]

to reclaim Malwa, Nizamul Mulk arrived in Bhopal from Delhi with 70,000 men, facing opposition from Bajirao and his 80,000-strong force. In the ensuing battle, the Marathas encircled the Nizam's forces, compelling him to seek peace. A treaty was negotiated, wherein the Nizam conceded the entire subah of Malwa to the Peshwa and relinquished complete sovereignty over the lands between the Narmada and Chambal rivers. Additionally, the Nizam committed to obtaining a substantial cash tribute from the Mughal Emperor. Fearing the Nizam's formidable artillery, Bajirao opted for the cession of Malwa rather than further engagement.[31][32]

Bajirao's invasion of Deccan (1739)[edit]

In 1739, as Nizam resisted Nader Shah's invasion in the North, Bajirao led a Deccan invasion with 50,000 men. Upon learning of the invasion, Nasir Jung mobilized 10,000 men to counter it. A decisive battle unfolded at the Godavari River, where Bajirao was severely beaten and the Nizam's army won.[33]

The outcomes of this conflict are recounted differently in historical records. Some assert that Nasir Jung defeated Bajirao, compelling his surrender. Conversely, other accounts suggest that Bajirao besieged Nasir Jung in the Aurangabad fort, ultimately forcing him to cede the districts of Nemad and Khargaon.[34][33]

According to the treaty:

- Marathas lost their right to collect Chauth from 6 provinces of Deccan.

- Khargaon and Nemad were given to Bajirao as Jagir.

- Bajirao promised not to invade Deccan again.[33]

This marked Bajirao's final battle, concluding with his death on 28 April 1740. His son Balaji Bajirao became the next Peshwa.[35]

I am involved in difficulties, in debt and in disappointment and like a man ready to swallow poison; near the Raja are my enemies and should I at this time go to Satara, they will put their feet on my breast. I should be thankful if I could meet death

— Bajirao's letter after the battle[36]

Siege of Trichinopoly (1743)[edit]

Raghoji Bhonsle, the Maratha chief who established Nagpur Kingdom, advanced to Trichinopoly, imprisoning Chanda Sahib on 28 May 1741. Despite Chanda Sahib's offer of Rs. 7 lakh to the Marathas for his release, the Mysore Hindu king Krishnaraja Wodeyar II insisted on the Marathas either killing or imprisoning Chanda Sahib and reinstating Hindu Nayaka rule. Bada Sahib, Chanda Sahib's brother, met his demise at the hands of the Marathas on 1 October 1741.[37] It appears that Safdar Ali Khan, the new nawab of Carnatic, unable to meet the tribute demanded by the Marathas, agreed to cede Trichinopoly to them. After capturing Trichinopoly, the Marathas dispatched 40,000 of their horsemen back to Mysore with Chanda Sahib. Approximately 20,000 cavalry, led by Murari Rao, remained in Trichinopoly. The Marathas, during their return, plundered Trichinopoly and its populace.[38][37]

In 1743, Nizam initiated a siege on Trichinopoly, compelling Murari Rao to surrender. Murari Rao found himself without support from his Maratha superiors, notably because Maratha Emperor Shahu I was deeply involved in expeditions aimed at extending Maratha dominance over Mughal-held Delhi, Bengal, and Odisha.[39] Simultaneously, internal conflicts surfaced between Maratha general Raghoji I Bhonsle and Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao, eventually leading to the disintegration of the Maratha empire. They reached an agreement, wherein the Nizam granted him governance of the hill fort of Penukonda, the surrounding areas, and 200,000 rupees. The six-month siege concluded on 29 August 1743. The surrender of Trichinopoly, coupled with the loss of the Madurai territory (administered by Maratha Lieutenant Officer Appaji Rao, captured in 1741), marked the end of Maratha suzerainty in the Carnatic region. This loss relinquished their direct rule, allowing the Nizam to reclaim authority over the Deccan region.[40][38]

According to the terms of the Trichinopoly agreement, if Dalavayi (Wodeyar) desired the control of Trichinopoly, he was required to pay 10,000,000 rupees to the Nizam. The Dalavayi, facing a financial crisis after paying substantial tributary taxes, including 50,000,000 rupees to Maratha ruler Raghoji in 1740–1741 following the Maratha invasion of the Carnatic region, the Dalavayi were unable to meet the stipulated sum. In October 1743, the Nizam departed for Deccan.[41]

After the Death of the Asaf Jah I and Shahu[edit]

Nizamul Mulk Asaf Jah I passed away on June 1, 1748, at the age of 77 in Burhanpur. He was laid to rest at the mausoleum of Shaikh Burhan ud-din Gharib Chisti in Khuldabad, near Aurangabad, the same location where his mentor Aurangzeb is also interred.[42] Following his father's demise, Nasir Jung ascended to the throne and ruled from 1748 to 1750.[43]

In the two years leading up to his death in 1749, Shahu recognized the growing likelihood of a civil war among various Maratha leaders due to the absence of a clear heir. Sambhaji II, a longstanding rival from the Kolapur line, was opposed by the Peshwa and there were no other suitable heirs. Tarabai proposed Rajaram II, the grandson of Rajaram, claiming he had been raised in secret. Despite widespread scepticism, Shahu accepted the boy, and in his will, he urged all leaders to acknowledge Rajaram II and entrusted his care and the governance of the realm to the Peshwa. Thus, Rajaram II succeeded Shahu.[44] A succession dispute unfolded between Muzaffar Jang and Nasir Jang for the throne, with Muzaffar being the grandson (daughter's son) and Nasir being the son of the late Nizam. In the Carnatic, a similar conflict arose between Chanda Sahib and Anwaruddin Khan. The French supported Muzaffar Jang and Chanda Sahib, while the English backed Nasir Jang and Muhammad Ali, Anwaruddin's son. In 1749, Muhammad Ali's father fell in battle against Chanda Sahib at Ambur. Muzaffar Jang, aided by the French, claimed the Nizam of Hyderabad title. Nasir Jang, his rival, was treacherously murdered by the Nawabs of Kurnool and Cuddapah. While en route to Hyderabad from Pondicherry, Muzaffar Jang was also assassinated by the Nawabs of Cuddapah and Kurnool at Rayachoti.[45] Salabat Jang, the third son of the Asaf Jah I, secured victory and became the Nizam with the assistance of French troops commanded by Joseph François Dupleix and Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau from 1751 to 1762.[46] From 1751 to 1758, Bussy resided in Hyderabad, assisting Salabat Jang in solidifying his position. Additionally, he played a crucial role in Salabat Jang's conflicts with the Marathas and in managing diplomatic relations with the ruler of Mysore.[45]

Throughout the succession struggles, Ghaziuddin, the eldest son of the Nizam, persevered. Forming alliances with fellow Marathas such as the Bhonsles and the Holkars, he reached Aurangabad in late September 1752, garnering significant support from various nobles.

Bussey defeats Balaji Bajirao (1751)[edit]

Ghaziuddin, the eldest son of Nizam, with support in Aurangabad and Hyderabad, was compelled to seize power of Salabat Jung. Amassing 150,000 men in Delhi and securing backing from the Peshwa Balaji Rao, he decided to march on the Deccan in September 1751. Meanwhile, Bussy achieved his first diplomatic success for the Nizam by obtaining a firman from the emperor confirming Salabat as the ruler of the Deccan. Subsequently, he met Balaji Rao and, capitalizing on a lunar eclipse on the night of December 3 to 4, 1751, dealt a crushing defeat to the Maratha Peshwa.[47]

-

Balaji Bajirao

-

Bussey

On January 17, 1752, the Peshwa accepted the Peace of Ahmadnagar, compelling him to return all territories he had conquered from the viceroys of the Deccan since Nizamulmulk's death to Salabat. Despite this, Ghaziuddin persisted. Forming alliances with other Marathas, the Bhonsles and the Holkars, he reached Aurangabad in late September 1752, securing the support of numerous lords.[47] However, he died due to food poisoning in October 1752.[48]

Salabat Jung's campaign against Raghuji (1754)[edit]

Syed Lashkar Khan, who served as the Diwan of Nasir Jung at that time, resigned from his position due to the actions of Nobles like Shah Nawaz Khan. Following his resignation, Dupleix sought to apprehend him, but Bussey opposed this idea, fearing it would not be well-received by the people of the Deccan. Instead, Bussey advised Salabat Jung to appoint Lashkar Khan as the Subahdari of Berar. However, Berar was then under the control of Raghuji, the Maratha ruler of Nagpur. Salabat Jung launched a campaign against Raghuji, during which Raghuji had to relinquish control of Berar to Lashkar Khan. Salabat Jung returned to Hyderabad after this campaign in May 1754.[49]

Battle at Udgir (1760)[edit]

The Peshwa resumed hostilities with the Nizam, and by 9 November 1759, his cousin Sadashivrao Bhau secured the crucial Ahmadnagar fort. In January 1760, a formidable Maratha force led by the Peshwa’s brother Raghunath Rao and cousin Sadashivrao, along with Ibrahim Gardi’s artillery, initiated an invasion. The outnumbered Salabat Jang confronted them at Udgir. Facing overwhelming odds, the Nizam aimed to reach Dharur and join his detained troops. The Mughal force, only 7000 strong, was surrounded by 60,000 Maratha horses, becoming an easy target for French-drilled artillery. The situation favoured the Marathas, on February 3, 40,000 Marathas attacked the Nizam's rear guard, resulting in a significant disaster. The ensuing battle persisted until sunset, leaving the Nizam's army in no condition to continue. In February 1760, the Nizam made peace by ceding territory and paying six million rupees, yielding significant regions to the Peshwa, while Salabat retained limited territories under certain conditions.[50]

The Maratha defeat at the Battle of Panipat plunged Peshwa Balaji into depression, leading to his illness and eventual death in 1761. His minor son, Madhavrao I, then assumed the role of Peshwa. Internal debates ensued, fueled by the ambitious actions of his brother Raghunath Rao, ultimately weakening Maratha's power.[50][51]

Asaf Jah II's invasion of Maharashtra (1762)[edit]

In 1761, Nizam Ali Khan, also known as Asaf Jah II, the fourth son of Asaf Jah I, invaded Maharashtra and advanced to within fourteen miles of Pune. The Peshwa negotiated peace on 2 January 1762, relinquishing nearly half of his father's territorial gains in the Mughal Deccan. Nizam Ali returned to Bidar, took control of the government, and imprisoned Salabat Jang on 6 July 1762, leading to Salabat Jang's death two years later. The elusive emperor of Delhi endorsed the usurpation by appointing Nizam Ali as viceroy, conferring upon him the title of Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah II. With Nizam Ali's accession in 1762, a prolonged period of stability commenced in the affairs of the Mughal Deccan.[50] An alternate account of this campaign is that, during Nizam's invasion, Maratha troops led by Raghunathrao, numbering around 70,000 men, intercepted the Nizam at Uruli, located 'less than a day's march from Poona'. The Maratha forces overwhelmed Nizam Ali, prompting him to sue for peace. Raghunath Rao hastily granted favourable terms without consulting the Peshwa and other senior officers. Madhav Rao strongly opposed Raghunath's hurried peace agreement, anticipating that the Maratha forces would thoroughly humble the Nizam in action. Many Maratha officers criticized Raghunath Rao, accusing him of striking a secret deal with the Nizam, aiming to befriend him as a potential ally in a future contest for the Peshwa against his nephew. In response, Raghunath Rao offered his resignation from the regency, believing his services to the young Peshwa were 'indispensable' and hoping to retain his charge.[52]

-

Peshwa Madhavrao I

Battle of Alegaon (1762)[edit]

Raghunathrao, having defected from Madhavrao's side, formed alliances with Janoji Bhonsale of Nagpur and the Nizam of Hyderabad, sparking a civil war. Despite an inconclusive initial skirmish, Madhav Rao suffered defeat in a subsequent encounter at Alegaon. The Nizam's unexpected support for Raghunath Rao led to a dire situation. Recognizing the consequences, the young Peshwa halted fighting and surrendered. Through mediation by Maratha Sardar Malhar Rao Holkar, reconciliation was achieved. Raghunath Rao acknowledged Madhav Rao as the Peshwa and joint command of Maratha troops was entrusted to him in their united fight against common foes.[53] Following the battle, Madhavrao was forced to give all the territories of Nizam, which was captured from Udgir.[54]

Battle of Rakhshasbuvan (1763)[edit]

Madhavrao successfully raided Nizam's territories, plundered Bidar, and devastated parts of the Nizam's territory, which provoked the Nizam. In the battle of Rakshasbhuvan on the Godavari's bank, Madhavrao led the complete rout of the Nizam's army. The Marathas gained territories valued at 82 lakhs. Janoji Bhonsale of Nagpur and Gopalrao Patwardhan, former Nizam supporters, were won over with territories worth 32 lakhs and Miraj, respectively. The significant outcome was the end of Raghunathrao's regency.[55]

After the battle, the Nizam and Marathas maintained friendly relations with each other. In 1766, the Nizam allied with the British, aligning against Hyder Ali, the ruler of Mysore at that time. Given the Nizam's amicable ties with the Peshwa, the British assumed the Marathas would also support them against Haider. However, Haider managed to secure a treaty with the Marathas, breaking the alliance between the Nizam and the British. The joint assault by the Nizam and Mysore on the fort of Kaverypatnam led to the outbreak of the first Anglo-Mysore war.[56]

Subjugation of Marathas of Nagpur (1766)[edit]

Janoji Bhonsale, who succeeded Raghoji Bhonsale of Nagpur, refused to acknowledge Madhavrao's leadership as he was involved in intrigues with Haider Ali and supporting Raghunathrao. Madhavrao and the Nizam launched a campaign against the Marathas of Nagpur, eventually defeating Janoji after a month-long series of bloody operations. By the end of January 1766, Janoji was compelled to surrender territories that belonged to the Nizam and partly to Madhavrao. The majority of territories, previously granted to Janoji at Rakshasbhuvan by the Peshwa, were revoked. Lands valued at 15 lakhs of rupees per annum were returned to the Nizam, while a portion of territory worth 9 lakhs of rupees was annexed to the Peshwa's domains.[57][58]

Under the British involvement[edit]

During the Anglo-Mysore war of 1788-89, the British formed alliances with the Nizam and the Marathas. Following the conclusion of the war, the Marathas were granted Savnur, Lakshmeswar, and Kandgol in Dharwar, along with all the territory extending up to the Tungabhadra river. The Nizam acquired control over Cuddapah, Gooty, and the districts situated between the Krishna and Tungabhadra rivers.[59]

Battle of Kharda (1795)[edit]

In March 1795, the Maratha confederacy confronted the Nizam at Kharda to acquire cash and territories from the Nizam, led by Bajirao II, the then Peshwa. The Nizam fielded an army of 100,000 soldiers comprising cavalry, footmen, and gunners, along with 59 heavy guns and 3,850 bans. The Nizam's forces were supported by 16,000 state-owned bullocks and 55,000 belonging to the banjaras for transportation, while provisions of grain and ghee were sourced from Berar and Nanded. Both sides had Westernized troops, with Nizam's Westernized corps consisting of 124 European mercenaries under the French officer Raymond, alongside 20,000 cavalry. In Hyderabad during the latter half of the eighteenth century, a French corps had been established, originally composed of 300 to 400 European soldiers sent by Bussy to aid the Nizam, later commanded by Lally and then Raymond. By 1795, this French Corps numbered 15,000 infantry organized into 20 battalions. Facing Raymond's corps, the Peshwa deployed 10 battalions under Perron and four under Dudrencec. The Marathas also deployed soldiers equipped with bans, 60,000 cavalry, and 192 heavy cannons.[60] The French-Nizam relations lasted till 1798.[61]

The battle occurred on the bank of the Khar River, approximately seven miles southwest of Kharda, surrounded by hill tracts to the north, east, and southeast. The terrain around Kharda was uneven, undulated, and stony, hindering cavalry operations, and making infantry and artillery pivotal in the confrontation. In the battle, the Nizam suffered losses of 50 cannons and 500 men.[60]

The Nizam had to cede a large portion of his territory to the Marathas.[62]

Upon Arthur Wellesley's arrival in 1798, a forward policy of engagement and subsidiary alliances with the remaining powers was adopted to deter alliances between the French and entities like the Nizam, Tipu, or the Marathas. The Nizam, facing pressure from the Marathas, eagerly sought British assistance and signed a subordinate treaty in 1798. However, the Marathas, particularly Nana Fadnavis, remained cautious and suspicious of the British, opposing any treaty or formal engagement.[63]

Battle of Adganv (1803)[edit]

In 1803, Nizam Ali Khan fell seriously ill, during which Daulat Rao Shinde and the Bhonsale invaded the Nizam's territories. British forces, led by Colonel Stevenson and Wellesley, defeated the Marathas at the Battle of Adganv, resulting in the Nizam reclaiming all Maratha claims under Berar, effectively ending the Bhonsales' rule over Berar. Nizam Ali Khan passed away in 1803, and his son Sikander Jah, also known as Asaf Jah III, succeeded him.[64]

Third Anglo-Maratha War[edit]

The Hyderabad contingent also participated in the third Anglo-Maratha war and played a significant role in suppressing the Pindaris and capturing Nagpur. The Nizam's cavalry played a significant role in compelling the Peshwa to surrender to the British.[65] After the Third Anglo-Maratha War, the British exempted the Nizam from paying Chauth and declared them as the successors of the Peshwa. Additionally, territories belonging to the Marathas, such as Vaizapur and Kannad from the Peshwa, and Ellora and Aurangabad from Holkar, were annexed to the Nizam's dominions.[65]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 273–281. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ^ Nayeem, M. A. (2000). History of Modern Deccan, 1720/1724-1948: Political and administrative aspects. Abul Kalam Azad Oriental Research Institute. pp. 120–123.

- ^ Zubrzycki, John (15 September 2022). The Last Nizam: The Rise and Fall of India's Greatest Princely State. Pan Macmillan. p. 29. ISBN 978-93-95624-34-3.

- ^ Banarjee, A. C (1978). A Comprehensive History of India: 1712-1772, edited by A. C. Banerjee and D. K. Ghase. People's Publishing House. pp. 197–198.

- ^ Kulkarni, G. T. (1983). The Mughal-Maratha Relations: Twenty Five Fateful Years, 1682-1707. Department of History, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute. p. 154.

- ^ Kishore, Brij (1963). Tara Bai and Her Times. Asia Publishing House. p. 67.

- ^ Nayeem 2000, p. 24.

- ^ India, Numismatic Society of (1972). The Journal of the Numismatic Society of India. Numismatic Society of India, P.O. Hindu University. p. 63.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 193. ISBN 978-81-208-2326-6.

- ^ a b c Nayeem, M. A. (1985). Mughal Administration of Deccan Under Nizamul Mulk Asaf Jah, 1720-48 A.D. Jaico Publishing House. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-7224-325-8.

- ^ Cheema, G. S. (2002). The Forgotten Mughals: A History of the Later Emperors of the House of Babar, 1707-1857. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7304-416-8.

- ^ A History of the Freedom Movement: 1707-1831. Renaissance Publishing House. 1984. p. 236.

- ^ Nayeem 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Michell, George; Zebrowski, Mark (10 June 1999). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-56321-5.

- ^ G.S.Chhabra (2005). Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-1: 1707-1803). Lotus Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-81-89093-06-8.

- ^ Banarjee 1978, p. 201.

- ^ Banarjee 1978, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hussain Khan, Yosuf (1936). Nizam Ul Mulk Asaf Jahi Founder Of The Hyderabad State. The Basel mission press, Mangalore. pp. 72–74.

- ^ Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. p. 655. ISBN 978-81-291-0890-6.

- ^ a b Dhir, Krishna S. (1 January 2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-81-208-4301-1.

- ^ Pagdi, Setumadhava Rao; Rao, P. Setu Madhava (1963). Eighteenth Century Deccan. Popular Prakashan. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-7154-367-0.

- ^ Bhatia, O. P. Singh (1968). History of India, from 1707 to 1856. Surjeet Book Depot. p. 71.

- ^ a b Hussain Khan 1936, p. 181.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1 February 2007). The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Banarjee 1978, p. 208.

- ^ Ramaswami, N. S. (1984). Political History of Carnatic Under the Nawabs. Abhinav Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8364-1262-8.

- ^ Malik, Zahiruddin (1977). The Reign of Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748. Asia Publishing House. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-210-40598-7.

- ^ Hussain Khan 1936, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Gordon 2007, pp. 125–127.

- ^ G.S.Chhabra 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c Banarjee 1978, pp. 212.

- ^ G.S.Chhabra 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Hussain Khan 1936, p. 217.

- ^ Society, Pakistan Historical (1957). A History of the Freedom Movement: 1707-1831. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 174.

- ^ a b More, J. B. P. (1 November 2020). Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu and South India under French Rule: From François Martin to Dupleix 1674-1754. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-000-26372-5.

- ^ a b Ramaswami, N. S. (1984). Political History of Carnatic Under the Nawabs. Abhinav Publications. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8364-1262-8.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (7 December 2012). War in the Eighteenth-Century World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-230-37000-5.

- ^ Caldwell, Bishop R.; Caldwell, Robert (1989). A History of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0161-1.

- ^ Raj, Raghavendra (2004). "4". Early wonders of Mysore and Tamil Nadu a study in political-economic and cultural relations (Dalvoys relations with Tamil Nadu (1704-1761)). University of Mysore (Department of History). hdl:10603/92519. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Faruqui, Munis D. (2009). "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-Century India". Modern Asian Studies. 43 (1): 5–43. doi:10.1017/S0026749X07003290. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 20488070. S2CID 146592706.

- ^ Luther, Narendra (1995). Hyderabad: Memoirs of a City. Orient Longman. p. 410. ISBN 978-81-250-0688-6.

- ^ Gordon 2007, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Rao, P. Raghunadha (1983). History of Modern Andhra. Sterling Publishers. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Michell, George; Zebrowski, Mark (10 June 1999). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-56321-5.

- ^ a b Markovits, Claude (24 September 2004). A History of Modern India, 1480-1950. Anthem Press. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2.

- ^ Andhare, B. R. (1984). Bundelkhand Under the Marathas, 1720-1818 A.D.: A Study of Maratha-Bundela Relations. Vishwa Bharati Prakashan. p. 88.

- ^ Regani, Sarojini (1988). Nizam-British Relations, 1724-1857. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-81-7022-195-1.

- ^ a b c Rapson, Edward James; Haig, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard; Dodwell, Henry (1971). The Cambridge History of India. S. Chand. pp. 389–390.

- ^ G.S.Chhabra 2005, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 448.

- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 449.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (30 November 2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges [3 volumes]: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century [3 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-313-02799-4.

- ^ Kulkarni, Prof A. R. (1 July 2008). The Marathas. Diamond Publications. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-8483-073-6.

- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 542.

- ^ Mehta 2005, pp. 451–452.

- ^ Kulkarni 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 168.

- ^ a b Roy, Kaushik (30 March 2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849. Taylor & Francis. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ Regani 1988, p. 180.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 169.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Kate, P. V. (1987). Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724-1948. Mittal Publications. p. 16. ISBN 978-81-7099-017-8.

- ^ a b Regani 1988, p. 218-219.

- Wars involving the Maratha Empire

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- 1818 in India

- Conflicts in 1818

- Wars involving British India

- Wars involving the British East India Company

- Battles involving the Maratha Empire

- Conflicts in 1725

- 1725 in India

- History of Tiruchirappalli

- Wars involving Hyderabad

- History of Tamil Nadu

- History of Andhra Pradesh

- History of Karnataka

- 18th century in India