Jesus in comparative mythology

| Part of a series on |

|

The study of Jesus in comparative mythology is the examination of the narratives of the life of Jesus in the Christian gospels, traditions and theology, as they relate to Christianity and other religions. Although the vast majority of New Testament scholars and historians of the ancient Near East agree that Jesus existed as a historical figure,[1][2][3][4][nb 1][nb 2][nb 3] most secular historians also agree that the gospels contain large quantities of ahistorical legendary details mixed in with historical information about Jesus's life.[10] The Synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke are heavily shaped by Jewish tradition, with the Gospel of Matthew deliberately portraying Jesus as a "new Moses".[11] Although it is highly unlikely that the authors of the Synoptic Gospels directly based any of their accounts on pagan mythology,[12] it is possible that they may have subtly shaped their accounts of Jesus's healing miracles to resemble familiar Greek stories about miracles associated with Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine.[13][14] The birth narratives of Matthew and Luke are usually seen by secular historians as legends designed to fulfill Jewish expectations about the Messiah.[15]

The Gospel of John bears indirect influences from Platonism, via earlier Jewish deuterocanonical texts, and may also have been influenced in less obvious ways by the cult of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, though this possibility is still disputed.[16] Later Christian traditions about Jesus were probably influenced by Greco-Roman religion and mythology. Much of Jesus's traditional iconography is apparently derived from Mediterranean deities such as Hermes, Asclepius, Serapis, and Zeus and his traditional birthdate on 25 December, which was not declared as such until the fifth century, was at one point named a holiday in honour of the Roman sun god Sol Invictus. At around the same time Christianity was expanding in the second and third centuries, the Mithraic Cult was also flourishing. Though the relationship between the two religions is still under dispute, Christian apologists at the time noted similarities between them, which some scholars have taken as evidence of borrowing, but which are more likely a result of shared cultural environment. More general comparisons have also been made between the accounts about Jesus's birth and resurrection and stories of other divine or heroic figures from across the Mediterranean world, including supposed "dying-and-rising gods" such as Tammuz, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris, although the concept of "dying-and-rising gods" itself has received scholarly criticism.

Legendary material in the gospels

[edit]Synoptic gospels

[edit]

The majority of New Testament scholars and historians of the ancient Near East agree that Jesus existed as an historical figure.[1][2][3][4][nb 4][nb 5][nb 6][nb 7] While some scholars have criticized Jesus scholarship for religious bias and lack of methodological soundness,[nb 8] with very few exceptions such critics generally do support the historicity of Jesus and reject the Christ myth theory that Jesus never existed.[21][nb 9][23][24][25] There is widespread disagreement among scholars about the accuracy of details of Jesus's life as it is described in the gospel narratives, and on the meaning of his teachings,[nb 10][27][nb 11][29]: 168–173 [29] and the only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and that he was crucified under the orders of the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate.[27][29][30][31][32] It is also generally, although not universally, accepted that Jesus was a Galilean Jew who called disciples and whose activities were confined to Galilee and Judea, that he had a controversy in the Temple, and that, after his crucifixion, his ministry was continued by a group of his disciples, several of whom were persecuted.[33][34]

Nonetheless, most secular scholars generally agree that the gospels contain large amounts of material that is not historically accurate and is better categorized as legend.[10] In a discussion of genuinely legendary episodes from the gospels, New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman mentions the birth narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke and the release of Barabbas.[35] He points out, however, that, just because these accounts are not true does not mean that Jesus himself did not exist.[10] According to theologians Paul R. Eddy and Gregory A. Boyd, there is no evidence that the portrayal of Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels (the three earliest gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke) was directly influenced by pagan mythology in any significant way.[12][36] The earliest followers of Jesus were devout Palestinian Jews who abhorred paganism[37] and would have therefore been extremely unlikely to model accounts about their founder on pagan myths.[12]

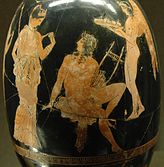

Despite this, several scholars have noticed that some of the healing miracles of Jesus recorded in the Synoptic Gospels bear similarities to Greek stories of miracles associated with Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine.[13][14][38] Brennan R. Hill states that Jesus's miracles are, for the most part, clearly told in the context of the Jewish belief in the healing power of Yahweh,[14] but notes that the authors of the Synoptic Gospels may have subtly borrowed from Greek literary models.[39] He states that Jesus's healing miracles chiefly differ from those of Asclepius by the fact that Jesus's are attributed to a human being on earth;[39] whereas Asclepius's miracles are performed by a distant god.[39] According to classical historians Emma J. Edelstein and Ludwig Edelstein, the most obvious difference between Jesus and Asclepius is that Jesus extended his healing to "sinners and publicans";[40] whereas Asclepius, as a god, refused to heal those who were ritually impure and confined his healing solely to those who thought pure thoughts.[40] Scholars disagree whether the parable of the rich man and Lazarus recorded in Luke 16:19–31 originates with Jesus or if it is a later Christian invention,[41] but the story bears strong resemblances to various folktales told throughout the Near East.[42]

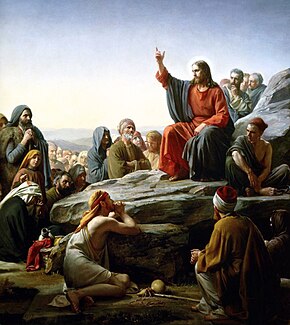

It is, however, widely agreed that the portrayal of Jesus in the gospels is deeply influenced by Jewish tradition.[11][45] According to E. P. Sanders, a leading scholar on the historical Jesus, the Synoptic Gospels contain many episodes in which Jesus's described actions clearly emulate those of the prophets in the Hebrew Bible.[45] Sanders states that, in some of these cases, it is impossible to know for certain whether these parallels originate from the historical Jesus himself having deliberately imitated the Hebrew prophets, or from later Christians inventing mythological stories in order to portray Jesus as one of them,[45] but, in many other instances, the parallels are clearly the work of the gospel-writers.[46] The author of the Gospel of Matthew in particular intentionally seeks to portray Jesus as a "new Moses".[11][47] Matthew's account of Herod's attempt to kill the infant Jesus, Jesus's family's flight into Egypt, and their subsequent return to Judaea is a mythical narrative based on the account of the Exodus in the Torah.[48][49][50][nb 12] In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus delivers his first public sermon on a mountain in imitation of the giving of the Law of Moses atop Mount Sinai.[17][18] According to New Testament scholars Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz, the teachings preserved in the sermon are statements that Jesus himself really said on different occasions that were originally recorded without context,[19] but the author of the Gospel of Matthew compiled them into an organized lecture and invented context for them in order to fit his portrayal of Jesus as a "new Moses".[19][17]

According to Sanders, the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke are the clearest examples of legends in the Synoptic Gospels.[15] Both accounts have Jesus born in Bethlehem, in accordance with Jewish salvation history, and both have him growing up in Nazareth,[15] but they present two different explanations for how that happened.[15][55] The accounts of the Annunciation of Jesus's conception found in Matthew 1:18–22 and Luke 1:26–38 are both modelled on the accounts of the annunciations of Ishmael, Isaac, and Samson in the Old Testament.[43][44][56] Matthew quotes from the Septuagint translation of Isaiah 7:14 to support his account of the virgin birth of Jesus.[57] The Hebrew text of this verse states "Behold, the young woman [ha'almāh] is with child and about to bear a son and she will call him Immanuel."[57] The Septuagint, however, translates the Hebrew word 'almāh, which literally means "young woman",[57] as the Greek word παρθένος (parthenos), which means "virgin".[57] Most secular historians therefore generally see the two separate accounts of the virgin birth from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke as independent legendary inventions designed to fulfill the mistranslated passage from Isaiah.[58][59][60] Sanders clarifies that the birth narratives are "an extreme case" resulting from the gospel authors' lack of knowledge about Jesus's birth and childhood;[61] no other part of the gospels relies so heavily on Old Testament parallels.[61] Sanders also notes that, despite the clearly intentional parallels, the "striking differences" between Jesus and the prophets of the Old Testament are also highly significant[62] and the gospels' accounts of Jesus's life on the whole do not closely resemble the lives of any of the figures in the Hebrew Bible.[61]

Although Jesus's crucifixion is one of the few events in his life that virtually all scholars of all different backgrounds agree really happened,[27][29][30][31][32] historians of religion have also compared it to Greek and Roman stories in order to gain a better understanding of how non-Christians would have perceived accounts of Jesus's crucifixion.[64] The German historian of religion Martin Hengel notes that the Hellenized Syrian satirist Lucian of Samosata ("the Voltaire of antiquity"), in his comic dialogue Prometheus, written in the second century AD (about two hundred years after Jesus), describes the god Prometheus being fastened to two rocks in the Caucasus Mountains using all the terminology of a Roman crucifixion:[63] he is nailed through the hands in such a manner as to produce "a most serviceable cross" ("ἐπικαιρότατος... ὁ σταυρος").[63] The gods Hermes and Hephaestus, who perform the binding, are shown as slaves whose brutal master Zeus threatens with the same punishment if they weaken.[63] Unlike the crucifixion of Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels, Lucian's crucifixion of Prometheus is a deliberate, angry mockery of the gods,[64] intended to show Zeus as a cruel and capricious tyrant undeserving of praise or adoration.[64] This is the only instance from all of classical literature in which a god is apparently crucified[64] and the fact that the Greeks and Romans could only conceive of a god being crucified as a form of "malicious parody" demonstrates the kind of horror with which they would have regarded Christian accounts of Jesus's crucifixion.[64]

American theologian Dennis R. MacDonald has argued that the Gospel of Mark is, in fact, a Jewish retelling of the Odyssey, with its ending derived from the Iliad, that uses Jesus as its central character in the place of Odysseus.[65] According to MacDonald, the gospels are primarily intended to show Jesus as superior to Greek heroes[65] and, although Jesus himself was a real historical figure, the gospels should be read as works of historical fiction centered on a real protagonist, not as accurate accounts of Jesus's life.[65] MacDonald's thesis that the gospels are modelled on the Homeric Epics has been met with intense scepticism in scholarly circles due to its almost complete reliance on extremely vague and subjective parallels.[66][67][68][69] Other scholars state that his argument is also undermined by the fact that the Gospel of Mark never directly quotes from either of the Homeric Epics[66][70][71] and uses completely dissimilar language.[66][70][71] Pheme Perkins also notes that many of the incidents in the Gospel of Mark that MacDonald claims are derived from the Odyssey have much closer parallels in the Old Testament.[71] MacDonald's argument, in a misunderstood form, has nonetheless become popular in non-scholarly circles, mostly on the internet, where it is used to support the Christ Myth theory.[72] MacDonald himself rejects this interpretation as too drastic.[72]

Gospel of John

[edit]

The Gospel of John, the latest of the four canonical gospels, possesses ideas that originated in Platonism and Greek philosophy,[78][79] where the "Logos" described in John's prologue was devised by the Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus and adapted to Judaism by the Jewish Middle Platonist Philo of Alexandria.[79] However, the author of the Gospel of John was not personally familiar with any Greek philosophy[80] and probably did not borrow the Logos theology from Platonic texts directly;[78][79] instead, this philosophy probably influenced earlier Jewish deuterocanonical texts, which John inherited and expanded his own Logos theology from.[78][79] In Platonic terminology, Logos was a universal force that represented the rationality and intelligibility of the world.[81] On the other hand, as adapted into Judaism, Logos becomes a mediating divine figure between God and man and mostly owed influence from Wisdom literature and biblical traditions, and by the time it was transmitted into Judaism, seems to have only retained the concept of the universality of the Platonic logos. Davies and Finkelstein write "This primeval and universal Wisdom had, at God's command, found itself a home on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. This mediatorial figure, which in its universality can be compared with the Platonic 'world-soul' or the Stoic 'logos', is here exclusively connected with Israel, God's chosen people, and with his sanctuary."[82]

Scholars have long suspected that the Gospel of John may have also been influenced by symbolism associated with the cult of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine.[16][73][74][75][76][77] The issue of whether the Gospel of John was truly influenced by the cult of Dionysus is hotly disputed,[16] with reputable scholars passionately defending both sides of the argument.[16] Dionysus was one of the best-known Greek deities;[83] he was worshipped throughout most of the Greco-Roman world[83] and his cult is attested in Palestine, Asia Minor, and Italy.[83] At the same time, other scholars have argued that it is highly implausible that the devout Christian author of the Gospel of John would have deliberately incorporated Dionysian imagery into his account[83] and instead argue that the symbolism of wine in the Gospel of John is much more likely to be based on the many references to wine found throughout the Old Testament.[83] In response to this objection, proponents of Dionysian influence have argued that it is possible that the author of the Gospel of John may have used Dionysian imagery in effort to show Jesus as "superior" to Dionysus.[83][84][85]

The first instance of possible Dionysian influence is Jesus's miracle of turning water into wine at the Marriage at Cana in John 2:1–11.[16][84] The account bears some resemblance to a number of stories that were told about Dionysus.[86] Dionysus's close associations with wine are attested as early as the writings of Plato[86] and the second-century AD Greek geographer Pausanias describes a ritual in which Dionysus was said to fill empty barrels that had been left locked inside a temple overnight with wine.[87][88] In the Greek novel Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius, written in the first or second century AD, a herdsman takes Dionysus into his home and offers him a meal, but he can only offer him the same thing to drink as his oxen.[89] Miraculously, Dionysus turns the drink into wine.[89] The account of turning water into wine does not occur in any of the Synoptic Gospels and is only found in the Gospel of John,[90] indicating that the author of the fourth gospel may have invented it.[90][84][85] A second occurrence of possible Dionysian influence is the allegory found in John 15:1–17, in which Jesus declares himself to be the "True Vine",[90] a title reminiscent of Dionysus, who was said to have discovered the first grape vine.[90]

Mark W. G. Stibbe has argued that the Gospel of John also contains parallels with The Bacchae, a tragedy written by the Athenian playwright Euripides that was first performed in 405 BC and involves Dionysus as a central character.[91][92] In both works, the central figure is portrayed as an incarnate deity who arrives in a country where he should be known and worshipped,[91][93] but, because he is disguised as a mortal, the deity is not recognized and is instead persecuted by the ruling party.[91][93] In the Gospel of John, Jesus is portrayed as elusive, intentionally making ambiguous statements to evade capture, much like Dionysus in Euripides's Bacchae.[91][94] In both works, the deity is supported by a group of female followers.[91][94] Both works end with the violent death of one of the central figures;[94] in John's gospel it is Jesus himself, but in The Bacchae it is Dionysus's cousin and adversary Pentheus, the king of Thebes.[94][nb 13]

Stibbe emphasizes that two accounts are also radically different,[98] but states that they share similar themes.[98] One of the most obvious differences is that, in The Bacchae, Dionysus has come to advocate a philosophy of wine and hedonism;[98] whereas Jesus in the Gospel of John has come to offer his followers salvation from sin.[98] Euripides portrays Dionysus as aggressive and violent;[98] whereas the Gospel of John shows Jesus as peaceful and full of mercy.[98] Furthermore, The Bacchae is set within an explicitly polytheistic world,[98] but the Gospel of John admits the existence of only two gods: Jesus himself and his Father in Heaven.[98]

Infancy Gospel of Thomas

[edit]The Infancy Gospel of Thomas is a short apocryphal gospel, probably written in the second century AD, describing Jesus's childhood.[99] It is unique as the only purported account of Jesus's childhood to survive from early Christian times.[99] It describes a variety of miracles attributed to the young Jesus.[100] It remained continuously in popular use throughout the Middle Ages up until the time of the Reformation.[101] Reidar Aasgaard has argued that the Infancy Gospel may have been partially intended for children[102] and discusses how the accounts in the gospel fit the genre of Greco-Roman fairy tales.[103] J. R. C. Cousland argues that the Infancy Gospel may have been originally written for a primarily pagan audience,[104] noting that the Greeks and Romans told stories about their gods' miraculous doings as children[105] and that miracle stories were often instrumental in converting pagans to Christianity.[106]

Syncretisms in late antiquity

[edit]Mithraism

[edit]

Around the same time that Christianity was expanding, the cult of the god Mithras was also spreading throughout the Roman Empire.[110] Very little is known for certain about the Mithraic cult because it was a "Mystery Cult", meaning its members were forbidden from disclosing the cult's beliefs to outsiders.[111][108] No Mithraic sacred texts have survived, if any such writings ever existed.[108][112] Consequently, it is disputed how much influence Christianity and Mithraism may have had on each other.[112] Michael Patella states that the similarities between Christianity and Mithraism are more likely a result of their shared cultural environment rather than direct borrowing from one to the other.[113] Christianity and Mithraism were both of Oriental origin[114] and their practices and respective saviour figures were both shaped by the social conditions in the Roman Empire during the time period.[112]

Most of what is known about the legendary life of Mithras comes from archaeological excavation of Mithraea, underground Mithraic sanctuaries of worship, which were found all across the Roman world.[115][116] Like Jesus, Mithras was seen as a divine saviour,[117][118] but, unlike Jesus, Mithras was not believed to have brought his salvation by suffering and dying.[115] Mithras was believed to have been born fully-grown from a rock,[119][120] a belief which is confirmed by a vast number of surviving sculptures showing him rising from the rock nude except for a Phrygian cap, clutching a sword in his right hand and a torch in his left.[119][120] In many depictions, the rock is also encircled by a snake.[121] In Mithraic cults primarily from the Rhine-Danube region, there are also representations of a myth in which Mithras shoots an arrow at a rock face, causing water to gush forth.[122] This myth is one of the closest parallels between Mithras and Jesus.[123] Both Christians and Mithraists used water as a symbol for their respective saviours.[123] In the New Testament, Jesus is referred to as the "water of life"[123] and a votive altar to Mithras from Poetovio proclaims him as the fons perennis ("the ever-flowing stream").[123]

In the center of every Mithraeum was a tauroctony,[116][109][108] a painting or sculpture showing Mithras as a young man, usually wearing a cape and Phrygian cap, plunging a knife into the neck or shoulder of a bull as he turns its head towards him, simultaneously turning his own head away.[109][124][108] A dog laps up the blood pouring from the bull's wound, from which emerges an ear of corn,[108] as a scorpion stings the bull's scrotum.[108] Human torchbearers stand on either side of the scene, one holding his torch upright and other upside-down.[108] A serpent is also present.[124][108] The exact interpretation of this scene is unclear,[108] but the image certainly depicts a narrative central to Mithraism[107][109][108] and the figures in it appear to correspond to the signs of the zodiac.[125][108][109] The closest parallel between Jesus and Mithras is the use of a ritual meal.[126] After slaying the bull, Mithras was believed to have shared the bull's meat with the sun-god Sol Invictus, a meal which is shown in Mithraic iconography and which was ritually reenacted by Mithraists as part of their liturgy.[127] Manfred Clauss, a scholar of the Mithraic cult, speculates that the similarities between Christianity and Mithraism may have made it easier for members of the Mithraic cult to convert to Christianity without having to give up their ritual meal, sun-imagery, candles, incense, or bells,[128] a trend which might explain why, as late as the sixth century, the Christian Church was still trying to stamp out the stulti homines who still paid obeisance to the sun every morning on the steps of the church itself.[129]

A few Christian apologists from the second and third centuries, who had never been members of the Mithraic cult and had never spoken to its members, claimed that the practices of the Mithraic cult were copied off Christianity.[108] The second-century Christian apologist Justin Martyr writes in his First Apology, after describing the Christian Eucharist, that "...the wicked devils have imitated [this] in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn."[130] The later apologist Tertullian writes in his De praescriptione haereticorum:

The devil (is the inspirer of the heretics) whose work it is to pervert the truth, who with idolatrous mysteries endeavours to imitate the realities of the divine sacraments. Some he himself sprinkles as though in token of faith and loyalty; he promises forgiveness of sins through baptism; and if my memory does not fail me marks his own soldiers with the sign of Mithra on their foreheads, commemorates an offering of bread, introduces a mock resurrection, and with the sword opens the way to the crown. Moreover has he not forbidden a second marriage to the supreme priest? He maintains also his virgins and his celibates.[131]

According to Ehrman, these writers were ideologically motivated to portray Christianity and Mithraism as similar because they wanted to persuade pagan officials that Christianity was not so different from other religious traditions, so that these officials would realize that there was no reason to single Christians out for persecution.[132] These apologists therefore intentionally exaggerated similarities between Christianity and Mithraism to support their arguments.[132] Scholars are generally wary of trusting anything these sources have to say about the Mithraic cult's alleged practices.[133]

Iconography

[edit]In late antiquity, early Christians frequently adapted pagan iconography to suit Christian purposes.[134][135] This does not in any way indicate that Christianity itself was derived from paganism,[134] only that early Christians made use of the pre-existing symbols that were readily available in their society.[134] Sometimes Christians deliberately used pagan iconography in conscious effort to show Jesus as superior to the pagan gods.[136] In classical iconography, the god Hermes was sometimes shown as a kriophoros, a handsome, beardless youth bearing a ram or sheep over his shoulders.[137] In late antiquity, this image developed a generic association with philanthropy.[137] Early Christians adapted images of this kind as representations of Jesus in his role of as the "Good Shepherd".[138]

Early Christians also identified Jesus with the Greek hero Orpheus,[139] who was said to have tamed wild beasts with the music of his lyre.[140] The Church Father Clement of Alexandria writes that Orpheus and Jesus are similar in that they have both been subject to admiration on account of their "songs",[141] but insists that Orpheus misused his gift of eloquence by persuading people to worship idols and "tie themselves to temporal things";[141] whereas Jesus, the singer of the "New Song" brings peace to men and frees them from the bonds of the flesh.[141] The later Christian historian Eusebius, drawing on Clement, also compares Orpheus to Jesus for having both brought peace to men.[142] One unusual possible instance of identification between Jesus and Orpheus is a hematite gem inscribed with the image of a crucified man identified as ΟΡΦΕΩΣ ΒΑΚΧΙΚΟΣ (Orpheos Bacchikos).[143][144] The gem has long been suspected to be a forgery created in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century,[145][144] but, if authentic, it may date to the late second or early third century AD.[143][144] If authentic, the gem would represent a remarkable instance of pagans adopting Christian iconography, rather than vice versa as is generally more common.[143] The gem was formerly housed at the Altes Museum in Berlin, but was lost or destroyed during World War II.[146][144]

Early Christians found it hard to criticize Asclepius because, while their usual tactics were to denounce the absurdity of believing in gods who were merely personifications of nature and to accuse pagan gods of being immoral,[147] neither of these could be applied to Asclepius, who was never portrayed as a personification of nature and whose stories were inscrutably moral.[147] The early Christian apologist Justin Martyr argued that believing in Jesus's divinity should not be hard for pagans, since it was no different from believing in the divinity of Asclepius.[147] Eventually, Christians adapted much of the iconography of Asclepius to suit the miracles of Jesus.[148][149] Images of Jesus as a healer replaced images of Asclepius and Hippocrates as the ideal physician.[149] Jesus, who was originally shown as clean-shaven, may have first been shown as bearded as a result of this syncretism with Asclepius,[150][151] as well as other bearded deities such as Zeus and Serapis.[151] A second-century AD head of Asclepius was discovered underneath a fourth-century AD Christian church in Gerasa, Jordan.[150]

In some depictions from late antiquity, Jesus was shown with the halo of the sun god Sol Invictus.[152] Images of "Christ in Majesty" seated upon a throne were inspired by classical depictions of Zeus and other chief deities.[151] By the fourth century AD, the recognizable image of Jesus as long-haired, bearded, and clad in long, baggy-sleeved clothing had fully emerged.[151] This widespread adaptation of pagan iconography to suit Jesus did not sit well with many Christians.[153] A fragment of a lost work by Theodor Lector preserves a miracle story dated to around 465 AD in which the bishop Gennadius of Constantinople was said to have healed an artist who had lost all strength in his hand after painting an image of Christ showing him with long, curly hair, parted in the same manner as traditional representations of Zeus.[153]

Christians also may have adapted the iconography of the Egyptian goddess Isis nursing her son Horus and applied it to the Virgin Mary nursing her son Jesus.[154][155] Some Christians also may have conflated stories about the Egyptian god Osiris with the resurrection of Jesus.[154][155] The title of kosmokrateros ("Ruler of the Cosmos"), which was eventually applied to Jesus, had previously been borne by Serapis.[156] The Church Father Jerome records in a letter dated to the year 395 AD that "Bethlehem... belonging now to us... was overshadowed by a grove of Tammuz, that is to say, Adonis, and in the cave where once the infant Christ cried, the lover of Venus was lamented."[157] This same cave later became the site of the Church of the Nativity.[157] The church historian Eusebius, however, does not mention pagans having ever worshipped in the cave,[157] nor do any other early Christian writers.[157] Peter Welten has argued that the cave was never dedicated to Tammuz[157] and that Jerome misinterpreted Christian mourning over the Massacre of the Innocents as a pagan ritual over Tammuz's death.[157] Joan E. Taylor has countered this argument by arguing that Jerome, as an educated man, could not have been so naïve as to mistake Christian mourning over the Massacre of the Innocents as a pagan ritual for Tammuz.[134] During the sixth century AD, some Christians in the Middle East borrowed elements from poems of Tammuz's wife Ishtar mourning over her husband's death into their own retellings of the Virgin Mary mourning over the death of her son Jesus.[158][159] The Syrian writers Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist both wrote laments in which the Virgin Mary describes her compassion for her son at the foot of the cross in deeply personal terms closely resembling Ishtar's laments over the death of Tammuz.[160]

-

Reconstruction by Quatremère de Quincy (1815) of Phidias's Statue of Zeus at Olympia, based on ancient descriptions and surviving copies

-

Thirteenth-century Byzantine mosaic of Christ in Majesty from the Basilica of San Frediano

-

Third-century AD Roman imperial repoussé silver disc found at Pessinus showing Sol Invictus with a parhelion

-

Byzantine mosaic of Jesus with his head surrounded by a halo (c. 526 AD)

-

Egyptian fresco from the fourth century AD showing Isis Lactans holding Harpocrates

-

Sixth-century AD icon of the enthroned Virgin and Child with saints and angels, and the Hand of God above, from Saint Catherine's Monastery, possibly the earliest iconic image of the subject to survive

Birthdate

[edit]The Bible never states when Jesus was born,[161][162][163] but, by late antiquity, Christians had begun celebrating his birth on 25 December.[162] In 274 AD, the Roman emperor Aurelian had declared 25 December the birthdate of Sol Invictus, a sun god of Syrian origin whose cult had been vigorously promoted by the earlier emperor Elagabalus.[164][163] Christians may have thought that they could attract more converts to Christianity by allowing them to continue to celebrate on the same day.[163] 25 December also falls around the same time as the Roman festival of Saturnalia, which was much older and more widely celebrated.[165][162] Many of the customs originally associated with Saturnalia eventually became associated with Christmas.[165][162] Early Christians may have also been influenced by the idea that Jesus had died on the anniversary of his conception;[163] because Jesus died during Passover and, in the third century AD, Passover was celebrated on 25 March,[163] they may have assumed that Jesus's birthday must have come nine months later, on 25 December.[163]

General comparisons

[edit]Aspects of Jesus's life as recorded in the gospels bear some similarities to various other figures, both historical and mythological.[166][167] Proponents of the Christ Myth theory frequently exaggerate these similarities as part of their efforts to claim that Jesus never existed as a historical figure.[166][167] Maurice Casey, the late Emeritus Professor of New Testament Languages and Literature at the University of Nottingham, writes that these parallels do not in any way indicate that Jesus was invented based on pagan "divine men",[168] but rather that he was simply not as perfectly unique as many evangelical Christians frequently claim he was.[168]

Miraculous birth

[edit]

Classical mythology is filled with stories of miraculous births of various kinds,[170][171][172][173] but, in most cases of divine offspring from classical mythology, the father is a god who engages in literal sexual intercourse with the mother, a mortal woman,[174][133] causing her to give birth to a son who is literally half god and half man.[175][133] A possible pagan precursor to the Christian story of the virgin birth of Jesus is an Athenian legend recounted by the mythographer Pseudo-Apollodorus.[169][176] According to this account, Hephaestus, the god of blacksmiths, once attempted to rape Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, but she pushed him away, causing him to ejaculate on her thigh.[177][169][178] Athena wiped the semen off using a tuft of wool,[177][169][178] which she tossed into the dust,[177][169][178] impregnating Gaia and causing her to give birth to Erichthonius,[177][169][178] whom Athena adopted as her own child.[177][179] Thus, Athena was able to produce a "son" without her losing her virginity.[179] The Roman mythographer Hyginus[176] records a similar story in which Hephaestus demanded Zeus to let him marry Athena since he was the one who had smashed open Zeus's skull, allowing Athena to be born.[177] Zeus agreed to this and Hephaestus and Athena were married,[177] but, when Hephaestus was about to consummate the union, Athena vanished from the bridal bed, causing him to ejaculate on the floor, thus impregnating Gaia with Erichthonius.[177]

Another comparable story from Greek mythology describes the conception of the hero Perseus.[180][181][182] According to the myth, Zeus came to Perseus's mother Danaë in the form of a shower of gold and impregnated her.[180][183][182] Although no surviving Greek text ever describes this as a "virgin birth",[183] the early Christian apologist Justin Martyr has his Jewish speaker Trypho refer to it as such in his Dialogue with Trypho.[183][182][170] Scholars have also compared the story of the virgin birth to the complex narratives revolving around the birth of Dionysus.[184][185] In most versions of the conception of Dionysus, Zeus was said to have come to the mortal woman Semele disguised as a mortal and had sex with her.[186] Zeus's wife Hera disguised herself as Semele's nurse and persuaded her to ask Zeus to show her his true, divine form.[186] Zeus eventually agreed, but, upon revealing his divine form, Semele was instantly incinerated by his lightning.[186] Zeus rescued the unborn infant Dionysus and sewed him inside his own thigh, giving birth to him himself when it was time.[187] In an alternative version of the story told by the Roman mythographer Hyginus, Dionysus was actually the son of Zeus and Persephone,[188] who was torn apart by the Titans.[188] Zeus rescued Dionysus's heart, ground it up, and mixed it into a potion, which he gave to Semele to drink, causing her to become pregnant with the infant who had been killed.[189]

According to M. David Litwa, the authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke consciously attempt to avoid portraying Jesus's conception as anything resembling pagan accounts of divine parentage;[190] the author of the Gospel of Luke tells a similar story about the conception of John the Baptist in effort to emphasize the Jewish character of Jesus's birth.[190] Nonetheless, Litwa argues that the accounts are unconsciously influenced by pagan stories of divine men, despite their authors' efforts to avert this.[191] Other stories of virgin births similar to Jesus's are referenced by later Christian writers.[192] The third-century AD Christian theologian Origen retells a legend that Plato's mother Perictione had virginally conceived him after the god Apollo had appeared to her husband Ariston and told him not to consummate his marriage with his wife,[180][193][194] a scene closely paralleling the account of the Annunciation to Joseph from the Gospel of Matthew.[180] Origen interpreted this story and others like it as prefiguring the reality made manifest by Jesus's virginal conception.[180][195] In the fourth century, the bishop Epiphanius of Salamis protested that, in Alexandria, at the temple of Kore-Persephone, the pagans enacted a "hideous mockery" of the Christian Epiphany in which they claimed that "Today at this hour Kore, that is the virgin, has given birth to Aion."[180]

Archetypal folkloric hero

[edit]Folklorist Alan Dundes has argued that Jesus fits all but five of the twenty-two narrative patterns in the Rank-Raglan mythotype,[196][197] and therefore more closely matches the archetype than many of the heroes traditionally cited to support it, such as Jason, Bellerophon, Pelops, Asclepius, Joseph, Elijah, and Siegfried.[198][197] Dundes sees Jesus as a historical "miracle-worker" or "religious teacher", accounts of whose life were told and retold through oral tradition so many times that they became legend.[199][200] Dundes states that analysing Jesus in the context of folklore helps explain some of the anomalies of the gospels, such as the fact that none of them give any information about Jesus's childhood and adolescence,[201] which Dundes explains by the fact that this is "precisely the case for almost all heroes of tradition".[201] Other scholars have strongly criticized Dundes's application of the Rank-Raglan mythotype to Jesus,[202][203] pointing out that Dundes draws the narrative patterns from different texts written centuries apart, without taking care to differentiate between them.[202][203] Dundes's application has also been criticized due to the Rank-Raglan mythotype's artificial nature and its lack of specificity to Hellenistic culture.[203] Nonetheless, Lawrence M. Wills states that the "hero paradigm in some form does apply to the earliest lives of Jesus", albeit not to the extreme extent that Dundes has argued.[202]

Dying-and-rising god archetype

[edit]

The late nineteenth-century Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer wrote extensively about the existence of a "dying-and rising god" archetype in his monumental study of comparative religion The Golden Bough (the first edition of which was published in 1890)[204][207] as well as in later works.[208] Frazer's main intention was to prove that all religions were fundamentally the same[209] and that all the essential features of Christianity could be found in earlier religions.[210] Although Frazer himself did not explicitly claim that Jesus was a "dying-and-rising god" of the supposedly typical Near Eastern variety, he strongly implied it.[211] Frazer's claims became widely influential in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century scholarship of religion,[205][206][204] but are now mostly rejected by modern scholars.[211][206][212]

The main examples of "dying-and-rising gods" discussed by Frazer were the Mesopotamian god Dumuzid/Tammuz, his Greek equivalent Adonis, the Phrygian god Attis, and the Egyptian god Osiris.[204][207][208] Dumuzid/Tammuz was a god of Sumerian origin associated with vegetation and fertility who eventually came to be worshipped across the Near East.[213] Dumuzid was associated with springtime agricultural fertility[213][214] and, when the crops withered during the hot summer months, women would mourn over his death.[213][215][216] Tammuz's categorization as a "dying-and-rising god" was based on the abbreviated Akkadian redaction of Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, which was missing the ending.[217][218] Since numerous lamentations over the death of Dumuzid had already been translated, scholars filled in the missing ending by assuming that the reason for Ishtar's descent was because she was going to resurrect Dumuzid and that the text could therefore be assumed to end with Tammuz's resurrection.[217]

Then, in the middle of the twentieth century, the complete, unabridged, original Sumerian text of Inanna's Descent was finally translated,[217][218] revealing that, instead of ending with Dumuzid's resurrection as had long been assumed, the text actually ended with Dumuzid's death.[217][218] The discovery of the Return of Dumuzid in 1963 briefly revived hopes that Dumuzid might once again be able to be categorized as a "dying-and-rising god",[217] but the text ultimately proved disappointing in this regard because it does not describe a triumph over death (as would be necessary for a true Frazerian "resurrection myth")[217][219] and instead does precisely the opposite and affirms the "inalterable power of the realm of the dead" by the fact that Dumuzid can only leave the Underworld when his sister takes his place.[217][219]

Frazer and others also saw Tammuz's Greek equivalent Adonis as a "dying-and-rising god",[205][204][220] despite the fact that he is never described as rising from the dead in any extant Greco-Roman writings[221] and the only possible allusions to his supposed resurrection come from late, highly ambiguous statements made by Christian authors.[221][nb 14] Attis is never described as being resurrected either;[222][221] although many myths surround his death, none of them ever claim that he was resurrected.[222][221] Osiris was never truly resurrected either;[219][223][224] in Egyptian myth, Osiris's brother Set was said to have murdered him, chopped his body into pieces, and scattered them across the land.[225][224] Osiris's devoted wife Isis collected his dismembered limbs and reassembled them,[225][224] allowing her to revive Osiris in the Duat, the Egyptian afterlife, where he became the king of the dead.[225][223][224]

In the late twentieth century, scholars began to severely criticize the designation of "dying-and-rising god" altogether.[208][219][226] In 1987, Jonathan Z. Smith concluded in Mircea Eliade's Encyclopedia of Religion that "The category of dying and rising gods, once a major topic of scholarly investigation, must now be understood to have been largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceedingly late or highly ambiguous texts."[219][221] He further argued that the deities previously referred to as "dying-and-rising" would be better termed separately as "dying gods" and "disappearing gods",[219][226] asserting that before Christianity, the two categories were distinct and gods who "died" did not return, and those who returned never truly "died".[219][226] By the end of the twentieth century, most scholars had come to agree that the notion of a "dying-and-rising god" was an invention[211][206][212] and that the term was not a useful scholarly designation.[211][206][212]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ While discussing the "striking" fact that "we don't have any Roman records, of any kind, that attest to the existence of Jesus," Ehrman dismisses claims that this means Jesus never existed, saying, "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees, based on clear and certain evidence."[5]

- ^ Robert M. Price, a former fundamentalist apologist turned atheist who says the existence of Jesus cannot be ruled out, but is less probable than non-existence, agrees that his perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars.[6]

Michael Grant (a classicist) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus, or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary."[7]

Maurice Casey, an irreligious Emeritus Professor of New Testament Languages and Literature at the University of Nottingham, concludes in his book Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? that "the whole idea that Jesus of Nazareth did not exist as a historical figure is verifiably false. Moreover, it has not been produced by anyone or anything with any reasonable relationship to critical scholarship. It belongs to the fantasy lives of people who used to be fundamentalist Christians. They did not believe in critical scholarship then, and they do not do so now. I cannot find any evidence that any of them have adequate professional qualifications."[8] - ^ "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church's imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that any more."[9]

- ^ While discussing the "striking" fact that "we don't have any Roman records, of any kind, that attest to the existence of Jesus," Ehrman dismisses claims that this means Jesus never existed, saying, "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees, based on clear and certain evidence."[5]

- ^ Robert M. Price, a former fundamentalist apologist turned atheist who says the existence of Jesus cannot be ruled out, but is less probable than non-existence, agrees that his perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars.[6]

- ^ Michael Grant (a classicist) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus, or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary."[7]

- ^ "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church's imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that any more."[9]

- ^ "...The point I shall argue below is that, the agreed evidentiary practices of the historians of Yeshua, despite their best efforts, have not been those of sound historical practice".[20]

- ^ "[F]arfetched theories that Jesus' existence was a Christian invention are highly implausible."[22]

- ^ Of "baptism and crucifixion", these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".[26]

- ^ "That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus ... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact."[28]

- ^ Some scholars argue for the historicity of the event. R. T. France acknowledges that the story is similar to that of Moses, but argues "[i]t is clear that this scriptural model has been important in Matthew's telling of the story of Jesus, but not so clear that it would have given rise to this narrative without historical basis."[51] France nevertheless notes that the massacre is "perhaps the aspect [of his story of Jesus' infancy] most often rejected as legendary".[52] Some scholars, such as Everett Ferguson, write that the story makes sense in the context of Herod's reign of terror in the last few years of his rule,[53] and the number of infants in Bethlehem that would have been killed – no more than a dozen or so – may have been too insignificant to be recorded by Josephus, who could not be aware of every incident far in the past when he wrote it.[54]

- ^ In the Bacchae, Pentheus is not crucified, but torn apart by the maenads, Dionysus's female followers. In a later euhemerized retelling of the myth of Pentheus from the third century BC, however, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus states that Dionysus crossed the Hellespont and "defeated the Thracian forces in battle. Lycurgus, whom he took prisoner, he blinded, tortured in every conceivable way and finally crucified."[95][96] This represents a unique instance in which Dionysus is shown as a god who crucifies his enemies.[97]

- ^ Origen discusses Adonis, (whom he associates with Tammuz), in his Selecta in Ezechielem ( "Comments on Ezekiel"), noting that "they say that for a long time certain rites of initiation are conducted: first, that they weep for him, since he has died; second, that they rejoice for him because he has risen from the dead (apo nekrôn anastanti)" (cf. J.-P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Graeca, 13:800).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Blomberg, Craig L. (2007). The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2807-4.

- ^ a b Carrier, Richard Lane (2014). On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-909697-35-5.

- ^ a b Fox, Robin Lane (2005). The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian. Basic Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-465-02497-1.

- ^ a b Dickson, John (24 December 2012). "Best of 2012: The irreligious assault on the historicity of Jesus". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b Bart D. Ehrman (22 March 2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God--Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperCollins. pp. 285. ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6.

- ^ a b James Douglas Grant Dunn (1 February 2010). The Historical Jesus: Five Views. SPCK Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-281-06329-1.

- ^ a b Michael Grant (January 2004). Jesus. Orion. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-898799-88-7.

- ^ Casey 2014, p. 243.

- ^ a b Richard A. Burridge; Graham Gould (2004). Jesus Now and Then. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 34. ISBN 978-0-8028-0977-3.

- ^ a b c Ehrman 2012, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c Ehrman 2012, pp. 198–199.

- ^ a b c Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Edelstein & Edelstein 1998, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c Hill 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e Sanders 1993, pp. 85–88.

- ^ a b c d e f Salier 2004, pp. 66–69.

- ^ a b c d Ehrman 2012, p. 199.

- ^ a b Sanders 1993, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d Theissen & Merz 1998, pp. 17–62.

- ^ Donald H. Akenson (29 September 2001). Surpassing Wonder: The Invention of the Bible and the Talmuds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-01073-1.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Markus Bockmuehl (8 November 2001). The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-521-79678-1.

- ^ Mark Allan Powell (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 168. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- ^ James L. Houlden (2003). Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: Entries A - J. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-856-3.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8028-4368-5.

- ^ James D. G. Dunn (2003). Jesus Remembered. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- ^ a b c William A. Herzog. Prophet and Teacher: An Introduction to the Historical Jesus (4 Jul 2005) ISBN 0-664-22528-4 pp. 1–6

- ^ John Dominic Crossan (1994). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperCollins. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-06-061662-5.

- ^ a b c d Mark Allan Powell (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- ^ a b Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 p. 339 states of baptism and crucifixion that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".

- ^ a b Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. p. 145. ISBN 0-06-061662-8.

That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus ... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact.

- ^ a b Amy-Jill Levine; Dale C. Allison Jr.; John Dominic Crossan (16 October 2006). The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-691-00992-9.

- ^ Herzog 2005, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Chilton & Evans 2002, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, p. 184.

- ^ Gerald O'Collins, "The Hidden Story of Jesus" New Blackfriars Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008

- ^ Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Cotter 2010, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Hill 2004, p. 68.

- ^ a b Edelstein & Edelstein 1998, p. 134.

- ^ van Eck 2016, pp. 262–265.

- ^ van Eck 2016, p. 265.

- ^ a b Farris 2015, p. 106.

- ^ a b Litwak 2005, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Sanders 1993, pp. 88–91, 112–113.

- ^ Sanders 1993, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Sanders 1993, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, p. 198.

- ^ Sanders 1993, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Casey 2010, p. 146.

- ^ France 2007, p. 83.

- ^ France 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Ferguson 2003, p. 390.

- ^ Maier 1998, p. 179, 186.

- ^ Casey 2010, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Casey 2010, pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b c d Seidler 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Bruner 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Machen 1987, p. 252.

- ^ Marchadour, Neuhaus & Martini 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c Sanders 1993, p. 88.

- ^ Sanders 1993, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Hengel 1977, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Hengel 1977, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 2013, pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b c Sandnes 2005, pp. 714–732.

- ^ Watts 2013, pp. 11–18.

- ^ Perkins 2007, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Meyer 2013, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Watts 2013, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Perkins 2007, p. 24.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2009, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Stibbe 1993, pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b Shorrock 2011, pp. 57–64.

- ^ a b Orchard 1998, pp. 129–132.

- ^ a b Kierspel 2006, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Stibbe 1994, pp. 131–134.

- ^ a b c Smalley 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c d Porter 2015, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Hurtado, Larry. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans, 2003, 366-7

- ^ Hornblower, Simon, Antony Spawforth, and Esther Eidinow, eds. The Oxford classical dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1996, 882

- ^ Sturdy, John, Louis Finkelstein, and William David Davies, eds. The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 223-224

- ^ a b c d e f Salier 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Kierspel 2006, p. 202.

- ^ a b Stibbe 1994, p. 132.

- ^ a b Salier 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.26

- ^ Salier 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Salier 2004, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Shorrock 2011, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e Stibbe 1993, p. 241.

- ^ Stibbe 1994, pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Stibbe 1994, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b c d Stibbe 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Hengel 1977, p. 13.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus Universal History 3.65.5

- ^ Hengel 1977, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stibbe 1994, p. 136.

- ^ a b Aasgaard 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Aasgaard 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Aasgaard 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Aasgaard 2010, pp. 196–198.

- ^ Aasgaard 2010, pp. 196–202.

- ^ Cousland 2017.

- ^ Cousland 2017, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Cousland 2017, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Ulansey 1989, pp. 9–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ehrman 2012, p. 213.

- ^ a b c d e Patella 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Patella 2006, pp. 1–2, 9.

- ^ Patella 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Patella 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Patella 2006, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Patella 2006, p. 9.

- ^ a b Patella 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b Ulansey 1989, p. 6.

- ^ Patella 2006, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Ulansey 1989, p. 125.

- ^ a b Ulansey 1989, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Clauss 2001, pp. 62–66.

- ^ Clauss 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Clauss 2001, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c d Clauss 2001, p. 72.

- ^ a b Ulansey 1989, p. 11.

- ^ Ulansey 1989, pp. 16–20.

- ^ Clauss 2001, pp. 72, 169.

- ^ Clauss 2001, pp. 112–116.

- ^ Clauss 2001, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Clauss 2001, p. 172.

- ^ First Apology of Justin Martyr, Chapter 66

- ^ Tertullian, De praescriptione haereticorum 4-.3-4

- ^ a b Ehrman 2012, pp. 213–214.

- ^ a b c Ehrman 2012, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1993, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Link 1995, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Taylor 2018, pp. 119–121.

- ^ a b Jensen 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Jensen 2000, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Friedman 2000, pp. 38–61.

- ^ Friedman 2000, pp. 55–57.

- ^ a b c Friedman 2000, p. 56.

- ^ Friedman 2000, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c Carotta & Eickenberg 2009, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Hengel 1977, pp. 13 and 22.

- ^ Carotta & Eickenberg 2009, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Carotta & Eickenberg 2009, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Edelstein & Edelstein 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Jefferson 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Ferngren 2009, p. 41.

- ^ a b Ogden 2013, p. 420.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 2018, p. 82.

- ^ Taylor 2018, p. 122.

- ^ a b Taylor 2018, p. 118.

- ^ a b Reid 2002, p. 24.

- ^ a b Johnson & Johnson 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Taylor 2018, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor 1993, p. 96.

- ^ Warner 2016, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Baring & Cashford 1991.

- ^ Warner 2016, p. 212.

- ^ Aldrete & Aldrete 2012, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d John 2005, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f Struthers 2012, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Aldrete & Aldrete 2012, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Aldrete & Aldrete 2012, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2012, pp. 207–218.

- ^ a b Casey 2014, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b Casey 2014, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f Deacy 2008, p. 82.

- ^ a b Warner 2016, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Litwa 2014, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Casey 2010, pp. 147–151.

- ^ Litwa 2014, pp. 38, 64–66.

- ^ Litwa 2014, pp. 64–66.

- ^ a b Kerényi 1951, p. 281.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kerényi 1951, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Burkert 1985, p. 143.

- ^ a b Deacy 2008, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c d e f g Warner 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b Litwa 2014, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Dundes 1980, p. 225.

- ^ a b c Machen 1987, p. 335.

- ^ Litwa 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Warner 2016, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c Kerényi 1951, p. 257.

- ^ Kerényi 1951, pp. 257–258.

- ^ a b Kerényi 1951, pp. 252–257.

- ^ Kerényi 1951, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Litwa 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Litwa 2014, pp. 40–43, 64–66.

- ^ Warner 2016, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Litwa 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Cooper 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Litwa 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Dundes 1980, pp. 230–236.

- ^ a b Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Dundes 1980, p. 235.

- ^ Dundes 1980, pp. 224–225, 325.

- ^ Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 314.

- ^ a b Dundes 1980, p. 236.

- ^ a b c Wills 2005, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Blomart 2004, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Ehrman 2012, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b c Barstad 1984, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b Mettinger 2004, p. 375.

- ^ a b c Barstad 1984, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, p. 222.

- ^ Barstad 1984, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Ehrman 2012, p. 223.

- ^ a b c Mettinger 2004, pp. 374–375.

- ^ a b c Ackerman 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Jacobsen 2008, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Jacobsen 2008, pp. 74–87.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 144.

- ^ a b c Mettinger 2004, p. 379.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith 1987, pp. 521–527.

- ^ Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 140–142.

- ^ a b c d e Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 143.

- ^ a b Smith 1987, p. 524.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b c d Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b c Pinch 2004, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c Mettinger 2004, p. 374.

Sources

[edit]- Aasgaard, Reidar (2010) [2009], The Childhood of Jesus: Decoding the Apocryphal Infancy Gospel of Thomas, Cambridge, England: James Clark & Co., ISBN 978-0-227-17354-1

- Ackerman, Susan (2006) [1989], Day, Peggy Lynne (ed.), Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-2393-7

- Aldrete, Gregory S.; Aldrete, Alicia (2012), "Fun for All: Holidays and Festivals", The Long Shadow of Antiquity: What Have the Greeks and Romans Done For Us?, New York City, New York and London, England: Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-4411-1663-5

- Assmann, Jan (2001) [1984], The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-3786-1

- Baring, Anne; Cashford, Jules (1991), The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image, London, England: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-019292-6

- Barstad, Hans M. (1984), The Religious Polemics of Amos: Studies in the Preaching of Am 2, 7B-8; 4,1-13; 5,1-27; 6,4-7; 8,14, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-07017-2

- Bennett, Clinton (2001). In search of Jesus: insider and outsider images. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-4915-3.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8

- Blomart, Alaine (2004), "Transferring the Cults of Heroes in Ancient Greece", in Aitken, Ellen Bradshaw; Maclean, Jennifer K. Berenson (eds.), Philostratus's Heroikos: Religion And Cultural Identity In The Third Century C.E, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 85–98, ISBN 90-04-13094-2

- Bruner, Frederick Dale (2004) [1987], Matthew: A Commentary, vol. 1, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., ISBN 0-8028-1118-3

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-36281-0

- Burridge, R; Gould, G (2004). Jesus Now and Then. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0977-3.

- Carotta, Francesco; Eickenberg, Arne (October 2009), Orpheos Bakkikos—The Missing Cross (PDF)

- Casey, Maurice (2010), Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching, New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark, ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3

- Casey, Maurice (2014), Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths?, New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-0-56744-762-3

- Cooper, Barry (2001), ""A Lump Bred Up in Darkness": Two Tellurian Themes of the Republic", in Planinc, Zdravko (ed.), Politics, Philosophy, Writing: Plato's Art of Caring for Souls, Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 978-0-8262-1343-3

- Cotter, Wendy (2010), The Christ of the Miracle-Stories: Portrait Through Encounter, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, ISBN 978-0-8010-3950-8

- Chilton, Bruce D.; Evans, Craig A. (2002), Authenticating the Activities of Jesus, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, Inc., ISBN 0-391-04164-9

- Clauss, Manfred (2001) [2000], The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries, translated by Gordon, Richard, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-92978-4

- Cousland, J. R. C. (2017), Holy Terror: Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-0-567-66816-5

- Deacy, Susan (2008), Athena, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30066-7

- Dundes, Alan (1980), Interpreting Folklore, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-14307-1

- Eddy, Paul Rhodes; Boyd, Gregory A. (2007), The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, ISBN 978-0-8010-3114-4

- Edelstein, Emma J.; Edelstein, Ludwig (1998) [1945], Asclepius: Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5769-4

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2012), Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth, New York City, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-220644-2

- Farris, Stephen (2015), The Hymns of Luke's Infancy Narratives: Their Origin, Meaning and Significance, New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-4742-3139-8

- Ferguson, Everett (2003). Backgrounds of Early Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2221-5.

- Ferngren, Gary B. (2009), Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-9142-7

- France, R.T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2501-8.

- Friedman, John Block (2000), Orpheus in the Middle Ages, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 0-8156-2825-0

- Grant, Michael (1999) [1977]. Jesus. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-0899-3.

- Hengel, Martin (1977), Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Fortress Press, pp. 13 and 22, ISBN 0-8006-1268-X

- Herzog, William R. (2005), Prophet and Teacher: An Introduction to the Historical Jesus, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster Knox Press, ISBN 0-664-22528-4

- Hill, Brennan R. (2004), Jesus, the Christ: Contemporary Perspectives, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-62564-643-9

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (2008) [1970], "Toward the Image of Tammuz", in Moran, William L. (ed.), Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, pp. 73–103, ISBN 978-1-55635-952-1

- Jefferson, Lee M. (2014), Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-1-4514-7793-1

- Jensen, Robin Margaret (2000), Understanding Early Christian Art, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-20455-0

- John, J. (2005), A Christmas Compendium, New York City, New York and London, England: Continuum, p. 112, ISBN 0-8264-8749-1

- Johnson, Donald; Johnson, Jean (2007), Universal Religions in World History: Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, Explorations in World History, New York City, New York: MacGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-295428-9

- Kerényi, Karl (1951), The Gods of the Greeks, London, England: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27048-1

- Kierspel, Lars (2006), "Meaning and context of "the World"", The Jews and the World in the Fourth Gospel: Parallelism, Function, and Context, Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 978-3-16-149069-9

- Link, Luther (1995), The Devil: A Mask Without a Face, London, England: Reaktion Books, ISBN 0-948462-67-1

- Litwak, Kenneth D. (2005), Echoes of Scripture in Luke-Acts: Telling the History of God's People Intertextually, New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark International, ISBN 0-567-03025-3

- Litwa, M. David (2014), Iesus Deus: The Early Christian Depiction of Jesus as a Mediterranean God, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-1-4514-7985-0

- MacDonald, Dennis R. (2009), "My Turn: A Critique of Critics of 'Mimesis Criticism'", Occasional Papers of the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, 53, Claremont, California: The Institute for Antiquity and Christianity

- MacDonald, Dennis R. (2013), Mythologizing Jesus: From Jewish Teacher to Epic Hero, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-5891-5

- Machen, Gresham (1987), Virgin Birth of Christ, Ingram Press, ISBN 978-0-227-67630-1

- Maier, Paul L. (1998). "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem". In Summers, Ray; Vardaman, Jerry (eds.). Chronos, Kairos, Christos II: Chronological, Nativity, and Religious Studies in Memory of Ray Summers. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-582-3.

- Marchadour, A.; Neuhaus, D.; Martini, C. C. (2009), The Land, the Bible, and History: Toward the Land That I Will Show You, New York City, New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-2661-0

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2004), "The "Dying and Rising God": A Survey of Research from Frazer to the Present Day", in Batto, Bernard F.; Roberts, Kathryn L. (eds.), David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts, Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, ISBN 1-57506-092-2

- Meyer, Marvin (2013) [2011], "The Young Streaker in Secret and Canonical Mark", in Burke, Tony (ed.), Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery?: The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate: Proceedings from the 2011 York University Christian Apocrypha Symposium, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-62032-186-7

- Ogden, Daniel (2013), Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-955732-5

- Orchard, Helen (1998), Courting Betrayal: Jesus as Victim in the Gospel of John, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 161, vol. Gender, Culture, Theory 5, Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press Ltd., ISBN 978-1-85075-884-6

- Patella, Michael (2006), Lord of the Cosmos: Mithras, Paul, and the Gospel of Mark, New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark, ISBN 0-567-02532-2

- Perkins, Pheme (2007), Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels, Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8028-6553-3

- Pinch, Geraldine (2004) [2002], Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5

- Porter, Stanley E. (2015), John, His Gospel, and Jesus: In Pursuit of the Johannine Voice, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 102–104, ISBN 978-0-8028-7170-1

- Price, Robert M. (2000). Deconstructing Jesus. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-758-1.

- Price, Robert M. (2005). "New Testament narrative as Old Testament midrash". In Jacob Neusner and Alan J. Avery-Peck (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Midrash: Biblical Interpretation in Formative Judaism. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14166-7.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2002), Whose Pharaohs?: Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22197-4

- Sanders, E. P. (1993), The Historical Figure of Jesus, London, England, New York City, New York, Ringwood, Australia, Toronto, Ontario, and Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-014499-4

- Sandnes, Karl Olav (2005), "Imitatio Homeri?: An Appraisal of Dennis R. MacDonald's "Mimesis Criticism"", Journal of Biblical Literature, 124 (4), Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature: 715–732, doi:10.2307/30041066, JSTOR 30041066

- Salier, Willis Hedley (2004), The Rhetorical Impact of the Sēmeia in the Gospel of John, Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 3-16-148407-X

- Schweitzer, Albert (2000) [1913]. John Bowden (ed.). The Quest of the Historical Jesus (first complete ed.). London: SCM. ISBN 978-0-334-02791-1.

- Seidler, Naomi (2006), Faithful Renderings: Jewish-Christian Difference and the Politics of Translation, Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-74505-3

- Smalley, Stephen S. (2012) [1978], John: Evangelist and Interpreter, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, pp. 87–88, ISBN 978-1-62032-295-6

- Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987), "Dying and Rising Gods", in Eliade, Mircea (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. IV, London, England: Macmillan, pp. 521–527, ISBN 0-02-909700-2

- Shorrock, Robert (2011), The Myth of Paganism: Nonnus, Dionysus and the World of Late Antiquity, A&C Black, ISBN 978-1-4725-1966-5

- Stibbe, Mark W. G. (1993), "The Elusive Christ: A New Reading of the Fourth Gospel", The Gospel of John As Literature: An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Perspectives, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 90-04-09932-8

- Stibbe, Mark W. G. (1994) [1992], John as Storyteller: Narrative Criticism and the Fourth Gospel, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-47765-4

- Struthers, Jane (2012), The Book of Christmas: Everything We Once Knew and Loved about Christmastime, London, England: Ebury Press, pp. 17–21, ISBN 978-0-09-194729-3

- Taylor, Joan E. (1993), Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-814785-6

- Taylor, Joan E. (2018), What Did Jesus Look Like?, New York City, New York: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, ISBN 978-0-5676-7151-6

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0863-8.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2005). The Messiah Myth: The Near Eastern Roots of Jesus and David. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-08577-4.

- Ulansey, David (1989), The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-506788-6

- van Eck, Ernest (2016), The Parables of Jesus the Galilean: Stories of a Social Prophet, Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, ISBN 978-1-4982-3372-9

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000), Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., ISBN 978-0-8028-4368-5

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2003). "Nonexistence Hypothesis". In James Leslie Houlden (ed.). Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 658–660.

- Warner, Marina (2016) [1976], Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-963994-6

- Watts, Joel L. (2013), Mimetic Criticism and the Gospel of Mark: An Introduction and Commentary, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-62032-289-5

- Weaver, Walter P. (1999). The Historical Jesus in the Twentieth Century, 1900–1950. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity. ISBN 978-1-56338-280-2.

- Wells, G. A. (April–June 1969). "Stages of New Testament Criticism". Journal of the History of Ideas. 30 (2): 147–160. doi:10.2307/2708429. JSTOR 2708429.

- Wells, G. A. (January–March 1973). "Friedrich Solmsen on Christian Origins". Journal of the History of Ideas. 34 (1): 143–144. doi:10.2307/2708950. JSTOR 2708950.

- Wills, Laurence M. (2005) [1997], The Quest of the Historical Gospel: Mark, John and the Origins of the Gospel Genre, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-203-44200-8