Nanzhao

Nanzhao | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 738–902 | |||||||||||

Nanzhao and contemporary Asian polities, circa 800. | |||||||||||

Kingdom of Nanzhao as of 879 AD | |||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||||

| Capital | Taihe (before 779) Yangjumie (after 779) (both in present-day Dali City) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Nuosu Bai Middle Chinese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 738 | ||||||||||

• Overthrown | 902 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | China Laos Myanmar Vietnam | ||||||||||

| Nanzhao | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南詔 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南诏 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | འཇང་ཡུལ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese | Nam Chiếu Đại Lễ | ||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 南詔 大禮 | ||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | น่านเจ้า | ||||||||

| RTGS | Nanchao | ||||||||

| Lao name | |||||||||

| Lao | ໜານເຈົ້າ, ນ່ານເຈົ້າ, ນ່ານເຈົ່າ, ໜອງແສ (/nǎːn.tɕâw, nāːn.tɕâw, nāːn.tɕāw, nɔ̌ːŋ.sɛ̌ː/) | ||||||||

| Shan name | |||||||||

| Shan | လၢၼ်ႉၸဝ်ႈ (lâan tsāw) | ||||||||

| Nuosu (Northern Yi) name | |||||||||

| Nuosu (Northern Yi) | ꂷꏂꌅ (ma'shy'nzy) | ||||||||

Nanzhao (Chinese: 南詔, also spelled Nanchao, lit. 'Southern Zhao',[2] Yi language: ꂷꏂꌅ, Mashynzy) was a dynastic kingdom that flourished in what is now southwestern China and northern Southeast Asia during the 8th and 9th centuries, during the mid/late Tang dynasty. It was centered on present-day Yunnan in China, with its capitals in modern-day Dali City. The kingdom was officially called Dameng (大蒙) from 738 to 859 AD, Dali (大禮) from 859 to 877 and Dafengmin (大封民) from 877 to 902.

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]

Nanzhao encompassed many ethnic and linguistic groups. Some historians believe that the majority of the population were the Bai people[3] (then known as the "White Man") and the Yi people[4] (then known as the "Black Man"), but that the elite spoke a variant of Nuosu (also called Yi), a Northern Loloish language.[5] Scriptures unearthed from Nanzhao were written in the Bai language.[6]

The Cuanman people came to power in Yunnan during Zhuge Liang's Southern Campaign in 225. By the fourth century they had gained control of the region, but they rebelled against the Sui dynasty in 593 and were destroyed by a retaliatory expedition in 602. The Cuan split into two groups known as the Black and White Mywa.[7] The White Mywa (Baiman) tribes, who are considered the predecessors of the Bai people, settled on the fertile land of western Yunnan around the alpine fault lake Erhai. The Black Mywa (Wuman), considered to be predecessors of the Yi people, settled in the mountainous regions of eastern Yunnan.[8] These tribes were called Mengshe (蒙舍), Mengxi (蒙嶲), Langqiong (浪穹), Tengtan (邆賧), Shilang (施浪), and Yuexi (越析). Each tribe was known as a zhao.[9][10] In academia, the ethnic composition of the Nanzhao kingdom's population has been debated for a century.[11] Some non-Chinese scholars subscribed to the theory that the Tai ethnic group was a major component and later moved south into modern-day Thailand and Laos.[12] The historiography of the origins of Nanzhao people has attracted much interest.[13]

Among them, Mengshe zhao was recorded as Ma Shizi ( ꂷꏂꌅ ma shy nzy ) in Yi classics, which means "King of Golden Bamboo". Because it is located in the south, Mengshe was called Nanzhao or southern Zhao.

Founding

[edit]In 649, the chieftain of the Mengshe tribe, Xinuluo (細奴邏, Senola), son of Jiadupang and grandson of Shelong, founded the Great Meng (大蒙) and took the title of Qijia Wang (奇嘉王; "Outstanding King"). He acknowledged Tang suzerainty.[9] In 652, Xinuluo absorbed the White Mywa realm of Zhang Lejinqiu, who ruled Erhai Lake and Cang Mountain. This event occurred peacefully as Zhang made way for Xinuluo of his own accord. The agreement was consecrated under an iron pillar in Dali. Thereafter the Black and White Mywa acted as warriors and ministers respectively.[14][10] In 655, Xinuluo sent his eldest son to Chang'an to ask for the Tang dynasty's protection. The Tang emperor appointed Xinuluo as prefect of Weizhou, sent him an embroidered official robe, and sent troops to defeat rebellious tribes in 672, thus enhancing Xinuluou's position.[15] Xinuluo was succeeded by his son, Luoshengyan, who travelled to Chang'an to make tribute to the Tang. In 704, the Tibetan Empire made the White Mywa tribes into tributaries, whilst subjugating the Black Mywa.[7] In 713, Luoshengyan was succeeded by his son, Shengluopi, who was also on good terms with the Tang. He was succeeded by his son, Piluoge, in 733.[16]

Piluoge began expanding his realm in the early 730s. He first annexed the neighboring zhao of Mengsui, whose ruler, Zhaoyuan, was blind. Piluoge supported Zhaoyuan's son, Yuanluo, in his accession, and in turn weakened Mengsui. After Zhaoyuan was assassinated, Piluoge drove Yuanluo from Mengsui and annexed the territory. The remaining zhaos banded together against Piluoge, who thwarted them with an alliance with the Tang dynasty. Not long after 733, the Tang official Yan Zhenghui cooperated with Piluoge in a successful attack on the zhao of Shilang, and rewarded the Mengshe rulers with titles.[17][18]

Shige/gupi of Shilang was garrisoning the fort of Shihe, which, it will be recalled, was a little East of the present Xiaguan, at the Southern entrance to the Dali Plain. Shilang forces also occupied the fort of Shiqiao at the Southern end of the Tiancang Shan. While Yan Zhenghui and Geluofeng took Shihe and captured Shigepi, Piluoge himself struck at Shiqiao and prevented reinforcements from Shilang from interfering with what appear to have been the main operations. For having occupied Shihe, Piluoge was well placed to attack the Xier He people of the Dali Plain. Once again victory was his, though some of the conquered people managed to escape and make their way North, where they eventually came under the rule of the Jianlang Zhao at Jian Chuan, which will be mentioned in due course.[19]

— M. Blackmore

Two other zhaos also joined in the attack on Shilang: Dengdan ruled by Mieluopi and Langqiong ruled by Duoluowang. Piluoge moved to eliminate these competitors by bribing Wang Yu, the military commissioner of Jiannan (modern Sichuan based in Chengdu) to convince the Tang court to support him in uniting the Six Zhaos. Piluoge then made a surprise attack on Dengdan and defeated the forces of both Mieluopi and the ruler of Shilang, Shiwangqian. The zhao of Yuexi was annexed when its ruler, Bochong, was murdered by his wife's lover, Zhangxunqiu. Zhangxunqiu was summoned by the Tang court and beaten to death. The territory of Yuexi was bestowed to Piluoge. Bochong's son, Yuzeng, fled and resisted Nanzhao's expansion for some time before he was defeated by Piluoge's son, Geluofeng, and drowned in the Changjiang. Piluoge's step-grandson grew jealous of the preeminence of his step-father, Geluofeng, and sought to create his own zhao by allying with the Tibetan Empire. His plans leaked out and he was killed.[20][18]

In the year 737 AD, Piluoge (皮羅閣) united the Six Zhaos in succession, establishing a new kingdom called Nanzhao (Southern Zhao). In 738, the Tang granted Piluoge the Chinese-style name Meng Guiyi ("return to righteousness")[21] and the title of "Prince of Yunnan".[22] Piluoge set up a new capital at Taihe in 739, (the site of modern-day Taihe village, a few miles south of Dali). Located in the heart of the Erhai valley, the site was ideal: it could be easily defended against attack and it was in the midst of rich farmland.[23] Under the reign of Piluoge, the White Mywa were removed from eastern Yunnan and resettled in the west. The Black and White Mywa were separated to create a more solidified caste system of ministers and warriors.[10]

During the Kaiyuan reign period (713–741), the ruler of Nanzhao, desired to annex the other four polities to create a kingdom, so he invited the four rulers to a banquet to celebrate the xinghui festival 星回節 on the sixteenth day of the twelfth lunar month. He set fire to the building, and then ordered the wives of the four rulers to search for their husband’s bones and take them home. At first, Cishan, the wife of the ruler of Dengdan, could not find the bones of her husband, but she located them by searching for the iron bracelet that [she] asked her husband wear on his arm. The ruler of Nanzhao marvelled at her intelligence and strongly desired to take her as his wife. Cishan replied saying, “I have not buried my deceased husband yet, so how could I dare think of marrying again so quickly?”, and then she shut tight her city gates. The Nanzhao army encircled the city, and all inside died of starvation after three months after completely exhausting their food supplies. [Before dying] Cishan declared, “I am going to report the injustice done to my husband to Heaven (Shangdi 上帝).” Horrified by this, the ruler of Nanzhao repented, and extolled her city as the “source of virtue”.[24]

— An Zixiu

Territorial expansion

[edit]Piluoge died in 748, and was succeeded by his son Geluofeng (閣羅鳳).[23] When the Chinese prefect of Yunnan attempted to rob Nanzhao envoys in 750, Geluofeng attacked, killing the prefect and seizing nearby Tang territory. In retaliation, the Tang governor of Jiannan (modern Sichuan), Xianyu Zhongtong, attacked Nanzhao with an army of 80,000 soldiers in 751. He was defeated by Duan Jianwei (段俭魏) with heavy losses (many due to disease) at Xiaguan.[25][26] Duan Jianwei's grave is two kilometres west of Xiaguan, and the Tomb of Ten Thousand Soldiers is located in Tianbao Park. In 754, another Tang army of 100,000 soldiers, led by General Li Mi (李宓), approached the kingdom from the north, but never made it past Mu'ege. By the end of 754, Geluofeng had established an alliance with the Tibetans against the Tang that would last until 794.[25] In the same year, Nanzhao gained control of the salt marshes of Yanyuan County, which it used to regulate the salt to its people, a practice that would continue during the reign of the Dali kingdom.[27]

Geluofeng accepted a Tibetan title and acted as part of the Tibetan Empire. His successor, Yimouxun, continued the pro-Tibetan policy. In 779, Yimouxun participated in a large Tibetan attack on the Tang dynasty. However the burden of having to support every single Tibetan military campaign against the Tang soon weighed on him. In 794, he severed ties with Tibet and switched sides to the Tang.[28][29] In 795, Yimouxun attacked a Tibetan stronghold in Kunming. The Tibetans retaliated in 799 but were repelled by a joint Tang-Nanzhao force. In 801 Nanzhao and Tang in Battle of Dulu , Chinese and Nanzhao's forces defeated a contingent of Tibetan and Abbasid slave soldiers. More than 10,000 Tibetan/Arabs soldiers were killed and some 6,000 captured.[30] Nanzhao captured seven Tibetan cities and five military garrisons while more than a hundred fortifications were destroyed. This defeat shifted the balance of power in favor of the Tang and Nanzhao.[31]

Attack on Sichuan

[edit]During the reign of Quanlongcheng (r.809-816), the ruler behaved without constraint, and was killed by Wang Cuodian, a powerful governor. The military generals in Nanzhao had become powerful after the victory in Tibet. Wang Cuodian installed a puppet ruler Quanlisheng. However, Quanlisheng quickly took power back three years later before he was himself replaced by Quanfengyou, with the aid of the generals. Quanfengyou and Wang Cuodian, who remained a powerful general, were instrumental in the expansion of Nanzhao territory.[32] Nanzhao expanded into Myanmar,[33] conquering the Pyu city-states in the 820s, finally defeating the Tagaung Kingdom in 832.[34]

In 829, Wang Cuodian attacked Chengdu, but withdrew the following year.[35] Wang Cuodian's invasion was not to take Sichuan but to push its territorial boundaries north and take the resources south of Chengdu.[36] The advance of Nanzhaos' army was almost unopposed; the attack took advantage of chaos created in Sichuan by its governor, Du Yuanying. Bilateral relations between Nanzhao and Tang became delicate, as Wang Cuodian refused to step retreat from Yizhou, saying that Nanzhao had remained a loyal tributary and was only punishing Du Yuanying at the request of Tang soldiers.[37]

In the same year of 830, Nanzhao renewed contact with Tang. The next year, at the request of Li Deyu, Nanzhao released more than four thousand prisoners of war, including Buddhist monks, Daoist priests, and artisans, who had been captured during the Yizhou incident. Frequent visits to Chang’an by Nanzhao delegations followed and continued until the end of Emperor Wuzong’s reign in 846. During these sixteen years, Nanzhao progressed rapidly in state building. Through its students dispatched to Yizhou, Nanzhao borrowed heavily from Tang administrative practice. There was much building of public works and a great expansion of monasteries. Nanzhao also expanded its realm to the Indochina peninsula. They invaded Biaoguo (one of the Pyu city-states, present-day Prome in Upper Burma) in 832 and brought back three thousand prisoners of war; shortly after, in 835, they subdued Michen (near the mouth of the Ayeyarwady River in lower Burma).[38]

— Wang Zhenping

In the 830s, they conquered the neighboring kingdoms of Kunlun to the east and Nuwang to the south.[39]

Invasion of Annan

[edit]In 846, Nanzhao raided the southern Tang circuit of Annan.[39] Relations with the Tang broke down after the death of Emperor Xuanzong in 859, when the Nanzhao king Shilong treated Tang envoys sent to receive his condolences with contempt, and launched raids on Bozhou and Annan.[40] Shilong also killed Wang Cuodian. To recruit for his wars, Shilong ordered all men over the age 15 to join the army.[10] Anti-Tang locals allied with highland people, who appealed to Nanzhao for help, and as a result invaded the area in 860, briefly taking Songping before being driven out by a Tang army the next year.[41][42][43] Prior to Li Hu's arrival, Nanzhao had already seized Bozhou. When Li Hu led an army to retake Bozhou, the Đỗ family gathered 30,000 men, including contingents from Nanzhao to attack the Tang.[44] When Li Hu returned, he learned the Vietnamese rebels and Nanzhao had taken control over Annan out of his hand. In December 860, Songping fell to the rebels and Hu fled to Yongzhou.[44] In summer 861, Li Hu retook Songping but Nanzhao forces moved around and seized Yongzhou. Hu was banished to Hainan island and was replaced by Wang Kuan.[40][44]

Shilong attacked Annan again in 863, occupying it for three years. With the aid of locals, Nanzhao invaded with an army of 50,000 and besieged Annan's capital Songping in mid-January.[45] On 20 January, the defenders led by Cai Xi killed a hundred of the besiegers. Five days later, Cai Xi captured, tortured, and killed a group of besiegers known as the Púzǐ or Wangjuzi (according to some historians, the Puzi were ancestors of the Wa people. Description about them is indefinite[46]). A local official named Liang Ke was related to them, and defected as a result. On 28 January, a Nanzhao Buddhist monk, possibly from the Indian continent, was wounded by an arrow while strutting to and fro naked outside the southern walls. On 14 February, Cai Xi shot down 200 Puzi and over 30 horses using a mounted crossbow from the walls. By 28 February, most of Cai Xi's followers had perished, and he himself had been wounded several times by arrows and stones. The Nanzhao commander, Yang Sijin, penetrated the inner city. Cai Xi tried to escape by boat, but it capsized midstream, drowning him. The 400 remaining defenders wanted to flee as well, but could not find any boats, so they chose to make a last stand at the eastern gate. Ambushing a group of Nanzhao cavalry, they killed over 2,000 Nanzhao troops and 300 horses before Yang sent reinforcements from the inner city. After taking Songping, Nanzhao laid siege to Junzhou (modern Haiphong). A Nanzhao and rebel fleet of 4,000 men led by a native chieftain named Zhu Daogu (朱道古) was attacked by a local commander, who rammed their vessels and sank 30 boats, drowning them. In total, the invasion destroyed Chinese armies in Annan numbering over 150,000. Although initially welcomed by the locals in ousting Tang control, Nanzhao turned on them, ravaging the local population and countryside. Both Chinese and Vietnamese sources note that the Annanese locals fled to the mountains to avoid destruction.[42][45] A government-in-exile for the protectorate was established in Haimen (near modern-day Hạ Long).[47] Ten thousand soldiers from Shandong and all other armies of the Tang empire were called and concentrating at Halong Bay for reconquering Annan. A supply fleet of 1,000 ships from Fujian was organized.[48]

Tang counterattack

[edit]The Tang launched a counterattack in 864 under Gao Pian, a general who had made his reputation fighting the Türks and the Tanguts in the north. In September 865, Gao's 5,000 troops surprised a Nanzhao army of 50,000 while they were collecting rice from the villages and routed them. Gao captured large quantities of rice, which he used to feed his army.[48] A jealous governor, Li Weizhou, accused Gao of stalling to meet the enemy, and reported him to the throne. The court sent another general named Wang Yanqian to replace Gao. In the meantime, Gao had been reinforced by 7,000 men who arrived overland under the command of Wei Zhongzai.[49] In early 866, Gao's 12,000 men defeated a fresh Nanzhao army and chased them back to the mountains. He then laid siege to Songping but had to leave command due to the arrival of Li Weizhou and Wang Yanqian. He was later reinstated after sending his aid, Zeng Gun, who went to the capital as his representative and explained his circumstances.[50] Gao completed the retaking of Annan in fall 866, executing the enemy general, Duan Qiuqian, and beheading 30,000 of his men.[47]

According to G. Evans in his final monograph The Tai Original Diaspora, there were probably a quite large number of indigenous Tai-speaking people in Northern Vietnam that threw their support for Nanzhao against the Chinese, and when the Chinese came back in 864, many Tai people were also victims of following Chinese suppression.[51]

Siege of Chengdu

[edit]In 869, Shilong attacked Chengdu with the help of the Dongman tribe. The Dongman used to be an ally of the Tang during their wars against the Tibetan Empire in the 790s. Their service was rewarded with mistreatment by Yu Shizhen, the governor of Xizhou, who kidnapped Dongman tribesmen and sold them to other tribes. When the Nanzhao attacked Xizhou, the Dongman tribe opened the gates and welcomed them in.[52][53]

The battle for Chengdu was brutal and protracted. The Nanzhao soldiers used scaling ladders and battering rams to attack the city from four directions. The Tang defenders used hooks and robes to immobilize the attackers before showering them with oil and setting them on fire. The 3,000 commandos that Lu Dan had earlier handpicked were particularly brave and skillful in battle. They killed and wounded some 2,000 enemy soldiers and burned three thousand pieces of war equipment. After the frontal attacks failed, the Nanzhao troops changed their tactics. They dismantled the bamboo fences of nearby residential houses, wet them with water, and shaped them into a huge cage that could ward off stones, arrows, and fire. They then put this “bamboo tank” on logs and rolled it near the foot of the city wall. Hiding themselves in the cage, they started digging a tunnel. But the Tang soldiers also had a novel weapon waiting for them. They filled jars with human waste and threw them at the attackers. The foul smell made the cage an impossible place to hide and work. Jars filled with molten iron then fell on the cage, turning it into a giant furnace. The invaders, however, refused to give up. They escalated their operations by night attacks. In response, the Tang soldiers lit up the city wall with a thousand torches, thus effectively foiling the enemy’s plan.

Fierce battles in Chengdu had now lasted over a month. Zhixiang, the Tang envoy, believed that it was time to send a messenger to contact Shilong and let him know that peace was in the interest of both parties. He instructed Lu Dan to stop new initiatives against the enemy so that a peace talk with Nanzhao could proceed. Shilong responded positively to the Tang proposal and sent an envoy to fetch Zhixiang to Nanzhao for further negotiation. Unfortunately, a piece of misinformation derailed Zhixiang’s plan. The Tang soldiers believed that reinforcement had arrived at the suburbs of Chengdu to rescue them. They opened the city gate and dashed out to greet the relief troops. This sudden event puzzled the Nanzhao generals, who mistook it for a Tang attack and ordered a counteroffensive. Tangled fighting broke out in the morning and lasted into dusk. Nanzhao’s action also puzzled Zhixiang. He questioned Shilong’s envoy: “The Son of Heaven has decreed that Nanzhao make peace [with China], but your soldiers have just raided Chengdu. Why?” He then requested withdrawal of the Nanzhao soldiers as the prerequisite for his visit to Shilong. Zhixiang eventually canceled his visit. His subordinates convinced him that the visit would subject him to mortal danger because the “barbarians are deceitful.” This cancellation only convinced Shilong that Tang lacked sincerity in seeking peace. He resumed attacks on Chengdu but could not score a decisive victory.

The situation in Chengdu changed in favor of the defenders when Yan Qingfu, military governor of Jiannan East Circuit (Jiannan dongchuan), coordinated a rescue operation. On the eleventh day of the second month, Yan’s troops arrived at Xindu (present-day Xindu County), which was some 22 kilometers north of the besieged Chengdu. Shilong hurriedly diverted some of his forces to intercept the Tang troops, but he suffered a crushing defeat. Some two thousand Nanzhao soldiers were killed. Two days later, another Tang force arrived to inflict even greater casualties on Shilong. Five thousand soldiers were exterminated, and the rest retreated to a nearby mountain. The Tang force advanced to Tuojiang, a relay station merely 15 kilometers north of Chengdu. Now it was Shilong who anxiously sued for peace. But Zhixiang was in no hurry to make a deal with him: “You should first lift the siege and withdraw your troops.” A few days later, a Nanzhao envoy came again. He shuttled ten times between Shilong and Zhixiang in the same day, trying to work out an agreement, but to no avail. With the Tang reinforcement fast approaching Chengdu, Shilong knew that time was working against him. His soldiers intensified attacks on the city. Shilong was so desperate to complete the campaign that he risked his life and personally supervised operations on the front line. But it was too late. On the eighteenth day, the Tang rescue forces converged on Chengdu and engaged their enemy. That night, Shilong decided to abort his campaign.[54]

— Wang Zhenping

Nanzhao invaded again in 874 and reached within 70 km of Chengdu, seizing Qiongzhou, however they ultimately retreated, being unable to take the capital.

Your ancestor once served the Tibetans as a slave. The Tibetans should be your foes. Instead you have turned yourself into a Tibetan subject. How could you not even differentiate kindness from enmity? As for the hall of the former Lord of Shu, it is a treasure from the previous dynasty, not a place suitable for occupancy by you remote barbarians. [Your aggression] has angered the deities as well as the common people. Your days are numbered![55]

— Niu Cong, military governor of Chengdu, in response to the Nanzhao invasion of 873

End of territorial expansion

[edit]In 875, Gao Pian was appointed by the Tang to lead defenses against Nanzhao. He ordered all the refugees in Chengdu to return home. Gao led a force of 5,000 and chased the remaining Nanzhao troops to the Dadu River where he defeated them in a decisive battle, captured their armored horses, and executed 50 tribal leaders. He proposed to the court an invasion of Nanzhao with 60,000 troops. His proposal was rejected.[56] Nanzhao forces were driven from the Bozhou region, modern Guizhou, in 877 by a local military force organized by the Yang family from Shanxi.[53] This effectively ended Nanzhao's expansionist campaigns. Shilong died in 877.[57]

From Emperor Yizong’s time [r. 860–874], the barbarians [i.e., Nanzhao] sacked Annan and Yongzhou twice, marched into Qianzhong [southern Guizhou] once, and raided Xichuan [southern Sichuan] four times. Over these fifteen years, recruiting soldiers for and transporting supplies to [troops on the frontiers] have exhausted the entire country. As the lion’s share of taxes did not reach the capital [but were diverted to the frontier troops], the [imperial] treasury and the palace storehouses were emptied. Soldiers died of tropical diseases. Poverty turned commoners into robbers and thieves. Land in central China lay waste. This is all due to the war with Nanzhao.[58]

— Lu Xie, Chancellor of the Tang dynasty, 880

Decline

[edit]

Shilong's successor, Longshun, entered negotiations with the Tang for a marriage alliance, which was agreed to in 880. The marriage alliance never came to fruition owing to the Huang Chao rebellion. By the end of 880 the rebels had taken Luoyang and seized the Tong Pass. Longshun did not give up on the marriage however. In 883 he sent a delegation to Chengdu to fetch the Princess of Anhua. They brought with them one hundred rugs and carpets as betrothal gifts. The Nanzhao delegation was detained for two years due to a dispute in ceremony and failed to bring back the princess. In 897 Longshun was murdered by one of his own ministers. His successor, Shunhua, sent envoys to the Tang requesting restoration of friendly relations, but by this time the Tang emperor was merely a puppet figurehead of more powerful military governors. No response returned.[59]

In 902, the dynasty came to a bloody end when the chief minister (buxie), Zheng Maisi, murdered the royal family and usurped the throne, renaming it to Dachanghe (大長和, 902–928). In 928, a White Mywa noble, Yang Ganzhen (Jianchuan Jiedushi), aided the chief minister, Zhao Shanzheng, in overthrowing the Zheng family and establishing Datianxing (大天興, 928–929). The new regime lasted only a year before Zhao was killed by Yang, who created Dayining (大義寧, 929–937). Finally Duan Siping seized power in 937 and established the Dali Kingdom.[60][61]

Military

[edit]

Nanzhao had an elite vanguard unit called the Luojuzi, which means tiger sons, that served as full-time soldiers. For every hundred soldiers, the strongest one was chosen for service in the Luojuzi. They were outfitted with red helmets, leather armour, and bronze shields, but went barefoot. Only wounds to the front were allowed and if they suffered any wounds to their back, they were executed. Their commander was called Luojuzuo. The king's personal guards, known as the Zhunuquju, were recruited from the Luojuzi.[62]

Government

[edit]Nanzhao society was separated into two distinct castes: the administrative White Mywa living in western Yunnan, and the militaristic Black Mywa in eastern Yunnan. The rulers of Nanzhao were from the Mengshe tribe of the Black Mywa. Nanzhao modelled its government on the Tang dynasty with ministries (nine instead of six) and imperial examinations. However the system of governance and rule in Nanzhao was essentially feudal.[63][64] Sons of the Nanzhao aristocracy visited the Tang capital, Chang'an, to receive a Chinese education.[9]

Sources that believe Nanzhao was a Yi dominated society also traditionally hold it to be a slave society because of how central the institution was to Yi culture. The prevalence of the slave culture was so great that sometimes children were named after the quality and quantity of slaves they owned or their parents wished to own. For example: Lurbbu (many slaves), Lurda (strong slaves), Lurshy (commander of slaves), Lurnji (origin of slaves), Lurpo (slave lord), Lurha, (hundred slaves), Jjinu (lots of slaves).[65]

Language and ethnicity

[edit]

Extant sources from Nanzhao and the later Dali Kingdom show that the ruling elite used Chinese script.[66] Scriptures from Nanzhao unearthed in the 1950s show that it was written in the Bai language but Nanzhao does not seem to have ever attempted to standardize or popularize the script.[6]

Leading families around the Nanzhao capital adopted Chinese surnames such as Yang, Li, Zhao, Dong, and claimed Han Chinese ancestry; however, the rulers instead presented themselves as Ailao descendants from Yongchang.[67]

Bai and Yi

[edit]The ethnicity of Nanzhao's ruling elite is not clear. Both the Yi people and Bai people in modern Yunnan claim descent from Nanzhao's rulers.

In the histories of the Period of Division (311–589), as well as the Cuan kingdoms of the Sui-Tang period (581–907), are thought to have been ruled by the ancestors of today’s Yi, and at least one faction in an ongoing debate considers the Nanzhao kingdom, which ruled Yunnan and surrounding areas after 740, to have been a Yi-dominated polity.[4]

— Stevan Harrell

In Weishan Yi and Hui Autonomous County, the Yi people claim direct descent from Xinuluo, the founder of Mengshe (Nanzhao).[68]

... the ethnic identity of the Nanzhao rulers is still a matter for lively discussion (see Qi 1987), and the Yunnan origin of the Yi is disputed by those who think they came from the Northwest. With regard to the latter issue, a recent article by Chen Tianjun (1985) demonstrates even more clearly than Ma Changshou's book the power of the five-stage and Morganian historical schemes. According to Chen, the origin of the Yi goes back further, to the San Miao of classical History, who were always fighting against the Xia dynasty (C.2200-1600 B.C.E.).[11]

— Stevan Harrell

The Bai people also trace their ancestry to Nanzhao and the Dali Kingdom, but records from those kingdoms do not mention Bai.[69] "Bai barbarians" or "Bo people" were mentioned during the Tang dynasty and it is suspected that they might be the same name using different transcriptions; Bai and Bo were pronounced Baek and Bwok in the Tang period. The name Bo was first cited in the Lüshi Chunqiu (c. 241 and 238 BC) and appeared again in the Records of the Grand Historian (begun in 104 BC).[70] The earliest references to "Bai people", or the "Bo", in connection to the people of Yunnan are from the Yuan dynasty. A Bai script using Chinese characters was mentioned during the Ming dynasty.[69] Scriptures dated to the Nanzhao period used the Bai language.[6] According to Stevan Harrell, while the ethnic identity of Nanzhao's ruling elite is still disputed, the subsequent Yang and Duan dynasties were both definitely Bai.[71]

Forced migrations

[edit]

The Nanzhao king Yimouxun (r. 779-808) conducted forced resettlement of several ethnicities.

Before the early Ming, northwest Yunnan was mainly populated by non-Han ethnic peoples. Ethnic peoples recorded as residing in mountainous or semimountainous parts of Beisheng sub-prefecture included the Boren 僰人, Mosuo man 摩些蠻, Lisuo 栗些, Xifan 西番, Baiman 白蠻, Luoluo 羅羅 and Echang 峨昌. In addition, reportedly, seven ethnic groups, i.e., the Baiman, Luoluo, Mosuo, Dongmen 冬門, Xunding 尋丁 and Echang, were forcibly moved here from the Kunmi River 昆彌河 (today’s Miju River 彌苴河 in Dengchuan) by Nanzhao King Yimouxun 異牟尋 (reigned 779–808).[72]

— Huang Caiwen

Beisheng originally formed part of the territory occupied by an ethnic group known to Chinese dynasties as the Shi barbarians (Shiman 施蠻). The Nanzhao King, Yimouxun 異牟尋 (reigned 779–808), opened the area during the Zhenyuan period (785 to 804) of the Tang and named it Beifang Dan 北方賧. Yimouxun forcibly moved the White Barbarians (Baiman 白蠻) of the Mi River 瀰河 together with other peoples, such as the Luoluo 羅落 and Mosuo 麽些, to populate the region and then renamed it Chengji Dan 成偈賧 (later Shanju prefecture 善巨郡)... The Duan family 段氏 of the Dali kingdom changed the name to Chengji Zhen 成紀鎮 in 1048 (Qingli 8) and appointed Gao Dahui 高大惠 to govern...[73]

— Huang Caiwen

Bamar

[edit]Nanzhao's invasions of the Pyu city-states brought with them the Bamar people (Burmese people), who originally lived in present-day Qinghai and Gansu. The Bamar would form the Pagan Kingdom in medieval Myanmar.[74][75][76]

The earliest Bamar kings practiced the same patronymic naming tradition that the Nanzhao kings practiced: the last part of a father's name is used as the first part of the son's name.[77]

Religion

[edit]

Benzhuism

[edit]Almost nothing is known about pre-Buddhist religion in Nanzhao. According to Yuan dynasty sources, the Bai people practiced an indigenous religion called Benzhuism that worshiped local lords and deities. The Benzhu lords are spirits of people that died under special circumstances and are not hierarchically organized. Archaeological findings in Yunnan suggest that animal and human sacrifices were offered to the Benzhu lords around a metal pillar with the aid of bronze drums in return for wealth and health. The use of iron pillars for rituals seems to have been retained into the Dali Kingdom. The Nanzhao tuzhuan shows offerings to heaven occurring around one.[78][79] The Bai people have female shamans and share a worship of white stones similar to the Qiang people.[80][81]

Bimoism

[edit]Bimoism is the ethnic religion of the Yi people. The religion is named after the Shaman-priests known as bimo, which means 'master of scriptures',[82] who officiate at births, funerals, weddings and holidays.[83] One can become bimo by patrilinial descent after a time of apprenticeship or formally acknowledging an old bimo as the teacher.[84] A lesser priest known as suni is elected, but bimo are more revered and can read Yi scripts while suni cannot. Both can perform rituals, but only bimo can perform rituals linked to death. For most cases, suni only perform some exorcism to cure diseases. Generally, suni can only be from humble civil birth while bimo can be of both aristocratic and humble families.[85]

The Yi worshiped and deified their ancestors similar to the Chinese folk religion, and also worshiped gods of nature: fire, hills, trees, rocks, water, earth, sky, wind and forests.[83] Bimoists also worship dragons, believed to be protectors from bad spirits that cause illness, poor harvests and other misfortunes. Bimoists believe in multiple souls. At death, one soul remains to watch the grave while the other is eventually reincarnated into some living form. After someone dies they sacrifice a pig or sheep at the doorway to maintain relationship with the deceased spirit.[85]

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhism practiced in Nanzhao and the Dali Kingdom was known as Azhali (Acharya), founded around 821-824 by a monk from India called Li Xian Maishun. More monks from India arrived in 825 and 828 and built a temple in Heqing.[86] In 839, an acharya named Candragupta entered Nanzhao. Quanfengyou appointed him as a state mentor and married his sister Yueying to Candragupta. It was said that he meditated in a thatched cottage of Fengding Mountain in the east of Heqing, and became an "enlightened God." He established an altar to propagate tantric doctrines in Changdong Mountain of Tengchong. Candragupta continued to propagate tantric doctrines, translated the tantric scripture The Rites of the Great Consecration, and engaged in water conservancy projects. He left for his homeland later on and possibly went to Tibet to propagate his teachings. When he returned to Nanzhao, he built Wuwei Temple.[87]

In 851, an inscription in Jianchuan dedicated images to Maitreya and Amitabha.[88] The Nanzhao king Quanfengyou commissioned Chinese architects from the Tang dynasty to build the Three Pagodas.[88] The last king of Nanzhao established Buddhism as the official state religion.[89] In the Nanzhao Tushu juan, the Nanzhao Buddhist elite are depicted with light skin whereas the people who oppose Buddhism are depicted as short and dark skinned.[90]

The Three Pagoda Temple 三塔寺 controlled the Ranggong Chapel 讓公庵, which the Gao family constructed during the Nanzhao kingdom period. Friends of the famous Neo-Confucian scholar Li Yuanyang 李元陽 (1497–1580) supported the chapel by donating funds to buy farm land for its maintenance as late as the Jiajing reign period (1522–1566). According to tradition, seven holy monks 聖僧 constructed Biaoleng Temple during the Nanzhao kingdom period. A stele dated 1430 (Xuande 5) records that Zhao Yanzhen 趙彥貞 from a local family of officials renovated Longhua Temple (flourished during the Nanzhao to Dali kingdom periods) after its destruction by the Ming army.[91]

— Jianxiong Ma

Azhali is considered a sect of Tantrism or esoteric Buddhism. Acharya itself means guru or teacher in Sanskrit. According to Azhali practices among the Bai people, acharyas were allowed to marry and have children. The position of acharya was hereditary. The acharyas became state mentors in Nanzhao and held great influence until the Mongol conquest of China in the 13th century, during which the acharyas called upon various peoples to resist the Mongol rulers and later the Chinese during the Ming conquest of Yunnan. Zhu Yuanzhang banned the dissemination of Azhali Buddhism for a time before setting up an office to administer the religion.[92]

The area had a strong connection with Tantric Buddhism, which has survived to this day[93] at Jianchuan and neighboring areas. The worship of Guanyin and Mahākāla is very different from other forms of Chinese Buddhism.[94] Nanzhao likely had strong religious connections with the Pagan Kingdom in what is today Myanmar, as well as Tibet and Bengal (see Pala Empire).[95]

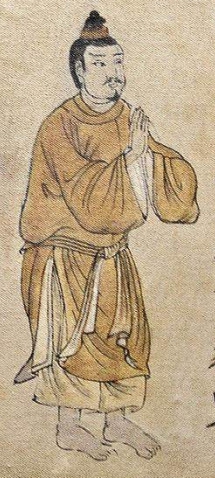

Gallery of Nanzhao rulers from the Kingdom of Dali Buddhist Volume of Paintings

[edit]-

Xinuluo r.649-674

-

Luosheng r.674-712

-

Shengluopi r.712-728

-

Piluoge r.(728-)738-748

-

Geluofeng r.748-779

-

Yimouxun r.779-808

-

Xungequan r.808-809

-

Quanlongcheng r.809-816

-

Quanli(sheng) r.816-823

-

Quanfengyou r.823-859

-

Shilong r.859-877

-

Longshun r.878-897

-

Shunhuazhen r.897-902

Family tree of monarchs

[edit]| Family of Nanzhao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[9]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ Stein, R. A. (1972) Tibetan Civilization, p. 63. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (pbk)

- ^ Yang, Yuqing (2017). Mystifying China's Southwest Ethnic Borderlands: Harmonious Heterotopia. Lexington Books. p. 43. ISBN 9781498502986.

- ^ Joe Cummings, Robert Storey (1991). China, Volume 10 (3, illustrated ed.). the University of California: Lonely Planet Publications. p. 705. ISBN 0-86442-123-0. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ a b Harrell 2001, p. 84.

- ^ C. X. George Wei (2002). Exploring nationalisms of China: themes and conflicts. Indiana University: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 195. ISBN 0-313-31512-4. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Wang 2004, pp. 280.

- ^ a b Beckwith 1987, p. 65.

- ^ "Cuan Culture in Yunnan – Yunnan Exploration: Yunnan Travel, Yunnan Trip, Yunnan Tours 2020/2021".

- ^ a b c d "Nanzhao 南詔 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ^ a b c d "The Faded Buddhist Country: A Brief History of Ancient Yunnan Constitution | by 山滇之城 | Medium". 19 August 2018.

- ^ a b Harrell 1995, p. 89.

- ^ Zhou, Zhenhe; You, Rujie (2017). Chinese Dialects and Culture. American Academic Press. p. 187. ISBN 9781631818844. Translated from 周振鹤; 游汝杰 (1986). 方言与中国文化. Shanghai: 上海人民出版社.

- ^ Baker, Chris (2002). "From Yue To Tai" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society: 17–19.

- ^ Yongjia, Liang (6 August 2018). Religious and Ethnic Revival in a Chinese Minority: The Bai People of Southwest China. Routledge. ISBN 9780429944031.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 101-102.

- ^ Blackmore 1960, p. 50.

- ^ Blackmore 1960, p. 52-3.

- ^ a b Wang 2013, p. 102.

- ^ Blackmore 1960, p. 53-4.

- ^ Blackmore 1960, p. 56.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 103.

- ^ Blackmore 1960, p. 57.

- ^ a b Blackmore 1960.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 57.

- ^ a b Herman 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Twitchett 1979, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Herman 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 137.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 157.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Wang 2013, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Coedès 1968, pp. 95, 104–105.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 33, 36.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 33, 35.

- ^ Yang, Yuqing (June 2008). The role of Nanzhao history in the formation of Bai identity (PDF) (Master of Arts). University of Oregon. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Wang 2013, pp. 117, 119.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 120.

- ^ a b Herman 2007, p. 35.

- ^ a b Herman 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 118.

- ^ a b Walker 2012, p. 183.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1983, p. 243.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 244.

- ^ Fiskesjö, Magnus (2021). Stories from an Ancient Land: Perspectives on Wa History and Culture. Berghahn Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-789-20888-7.

- ^ a b Schafer 1967, p. 68.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 246.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 247.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 124.

- ^ G. Evans (2014). The Tai Original Diaspora. Journal of the Siam Society (Report).

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 126.

- ^ a b Herman 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 127-8.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 129.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 131.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 134-5.

- ^ Bryson 2019, p. 94.

- ^ Bryson 2016, p. 37.

- ^ "罗苴子是什么意思_罗苴子的解释_汉语词典_词典网".

- ^ "全历史".

- ^ "The Bai ethnic minority".

- ^ "Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China".

- ^ Bryson 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Ann Heirman, Carmen Meinert, Christoph Anderl (2018). Buddhist Encounters and Identities Across East Asia. BRILL. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9789004366152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Between Winds and Clouds: Chapter 5".

- ^ a b Bryson 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Skutsch 2005, p. 350.

- ^ Harrell 1995, p. 87.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 94.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 105.

- ^ Moore 2007: 236

- ^ Harvey 1925: 3

- ^ Hall 1960: 11

- ^ Ann Heirman, Carmen Meinert, Christoph Anderl (2018). Buddhist Encounters and Identities Across East Asia. BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 9789004366152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bryson 2016, p. 31.

- ^ "圖片".

- ^ Cultural China, The Benzhu religion of the Bai. Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Skutch 2005, p. 350.

- ^ Berounsky, Daniel (15 December 2020). "Masters of Psalmody (Bimo): Scriptural shamanism in Southwestern China, by Aurélie Névot". European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (55): 102–106. doi:10.4000/ebhr.249.

- ^ a b Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. Abc-Clio. 10 February 2014. ISBN 9781610690188.

- ^ "Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China".

- ^ a b Zhen Wang (2018). "Out of the mountains" (PDF). Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

- ^ Howard, Angela F. "The Dhāraṇī pillar of Kunming, Yunnan: A legacy of esoteric Buddhism and burial rites of the Bai people in the kingdom of Dali, 937–1253", Artibus Asiae 57, 1997, pp. 33-72 (see pp. 43–44).

- ^ India China Encyclopedia Vol. 1 (2014), p. 256

- ^ a b Bryson 2016, p. 32.

- ^ "Nanzhao State and Dali State". City of Dali. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006.

- ^ Bryson 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Huang 2020, p. 55.

- ^ India China Encyclopedia Vol. 1 (2014), p. 151

- ^ Megan Bryson, "Baijie and the Bai: Gender and Ethnic Religion in Dali, Yunnan", Asian Ethnology 72, 2013, pp. 3-31

- ^ Megan Bryson, "Mahākāla worship in the Dali kingdom (937-1253) – A study and translation of the Dahei tianshen daochang yi", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 35, 2012, pp. 3-69

- ^ Thant Myint-U, Where China Meets India: Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia, Part 3

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrade, Tonio (2016). The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7..

- Asimov, M.S. (1998). History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting. UNESCO Publishing.

- Barfield, Thomas (1989). The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Basil Blackwell.

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008). The Woman Who Discovered Printing. Great Britain: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press.

- Blackmore, M. (1960). "The Rise of Nan-Chao in Yunnan". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 1 (2): 47–61. doi:10.1017/S0217781100000132.

- Bregel, Yuri (2003). An Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Brill.

- Bryson, Megan (2013), Baijie and the Bai

- Bryson, Megan (2016), Goddess on the Frontier: Religion, Ethnicity, and Gender in Southwest China, Stanford University Press

- Bryson, Megan (2019), The Great Kingdom of Eternal Peace: Buddhist Kingship in Tenth-Century Dali

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Translated by Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005). Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire: A Documentary History. Brill.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X. (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Otto Harrassowitz · Wiesbaden.

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900. Warfare and History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415239559.

- Graff, David Andrew (2016). The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7..

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. ISBN 978-1-4067-3503-1.

- Harrel, Stevan (1995), The History of the History of the Yi

- Harrel, Stevan (1995), Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Haywood, John (1998). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492. Barnes & Noble.

- Herman, John E. (2007). Amid the Clouds and Mist China's Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-02591-2.

- Herman, John (2009), The Kingdoms of Nanzhong China's Southwest Border Region Prior to the Eighth Century

- Huang, Caiwen (2020), The Lancang Guard and the Construction of Ming society in northwest Yunnan

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190053796.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964). The Chinese, their history and culture. Vol. 1–2. Macmillan.

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008). The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Schafer, Edward Hetzel (1967), The Vermilion Bird: T'ang Images of the South, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520011458

- Millward, James (2009). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press.

- Moore, Elizabeth H. (2007). Early Landscapes of Myanmar. Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 978-974-9863-31-2.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science & Civilisation in China. Vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013). Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang. Brill.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press.

- Shaban, M. A. (1979). The ʿAbbāsid Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29534-3.

- Sima, Guang (2015). Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤. Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī. ISBN 978-957-32-0876-1.

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires). Oxford University Press.

- Skutsch, Carl (2005), Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities, Routledge

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983), The Birth of the Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520074170

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780520074170

- Twitchett, Denis C. (1979). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 3, Sui and T'ang China, 589–906. Cambridge University Press.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012), East Asia: A New History, AuthorHouse, ISBN 978-1477265161

- Wang, Feng (2004). "Language policy for Bai". In Zhou, Minglang (ed.). Language policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and practice since 1949. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 278–287. ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- Wang, Zhenping (2013). Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War. University of Hawaii Press.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000). Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies). University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies. ISBN 0892641371.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0810860537.

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005). Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan. Institute for Asian and African Studies 7.

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992). Turkic peoples. 中国社会科学出版社.

- Yang, Bin (2008a). "Chapter 3: Military Campaigns against Yunnan: A Cross-Regional Analysis". Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (Second Century BCE to Twentieth Century CE). Columbia University Press.

- Yang, Bin (2008b). "Chapter 4: Rule Based on Native Customs". Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (Second Century BCE to Twentieth Century CE). Columbia University Press.

- Yang, Bin (2008c). "Chapter 5: Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese". Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (Second Century BCE to Twentieth Century CE). Columbia University Press.

- Yuan, Shu (2001). Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代. Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī. ISBN 957-32-4273-7.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. Hakluyt Society.

Further reading

[edit]- Backus, Charles (1981), The Nan-chao Kingdom and T'ang China's Southwestern Frontier, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22733-9.

- Chan, Maung (28 March 2005). "Theravada Buddhism and Shan/Thai/Dai/Laos Regions". Boxun News.