Nashville, Tennessee slave market

While the biggest slave market in the state was along the Mississippi River in Memphis, land routes connecting Nashville to the ports at New Orleans, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi, sufficed to deliver human cargo to and from Nashville.[1][2] By 1850, slaves were a major export of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and Nashville served that market with no fewer than eight slave-trade brokers.[3] These brokers sold slaves at multiple locations in the city, albeit generally in proximity to Cedar Street.

Nashville Market-House

[edit]An 1842 gazetteer mentioned the Market-House first in its list of the city's attractions: "The town is adorned with one of the largest and handsomest market-houses in the western country."[4]

The construction of the Nashville Market-House building, which had a copper roof and a landmark dome, was described in an 1890 history of the city:[5][6]

This market-house was built mostly in 1828, and completed in January, 1829. It was described, when completed, as being unequaled in extent, convenience, and elegance by any similar building in the United States, except that in Boston, Mass., which cost $500,000. The market-house in Nashville was two hundred and seventy feet long and sixty-two feet wide...In the center there were two elegant elliptical arches, each seventeen feet span in the clear , supported by a row of pillars, each two feet thick, extending the entire length of the building. At each end there were two stories, and in the second story two rooms, forty by twenty-eight feet each, besides four smaller rooms.

While the building was still in use in 1870, a guidebook writer had complaints:[7]

Strange to say, Nashville has but one General Market-house, and, if we may be allowed the suggestion, would intimate a very inferior one at that. Instead of well appointed market-places, distributed at convenient intervals throughout the City, like most of her rival sisters, the people of Nashville, from all quarters of the town, are compelled to resort to this mart for their supplies. However, in the absence of anything better arranged, or more attractive, as to appearances, the place is liberally patronized, and its business necessarily gives employment to hundreds of persons. A portion of the Market-house, as we understand, was built about the year 1827 or '28. In 1855 it was enlarged and remodelled, and the addition of the City Hall made to it; but the work, as intended, was never fully carried out, as it was proposed to build a public hall, extending over the entire market-place, and accessible from both the north and south ends. The present value of the Market-house is about $55,000. It contains 100 stalls. These stalls are a source of considerable revenue to the City, and yield about $45,000 per annum.

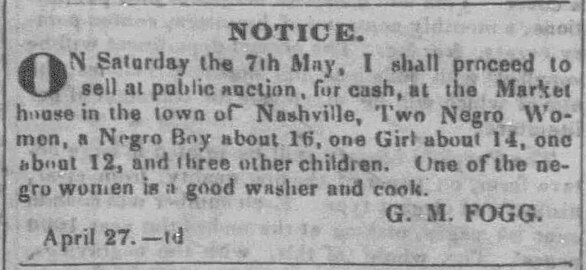

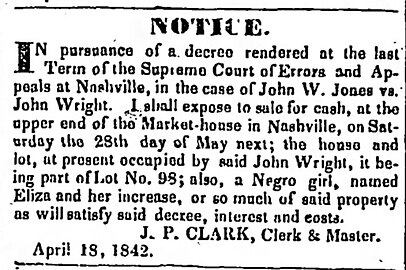

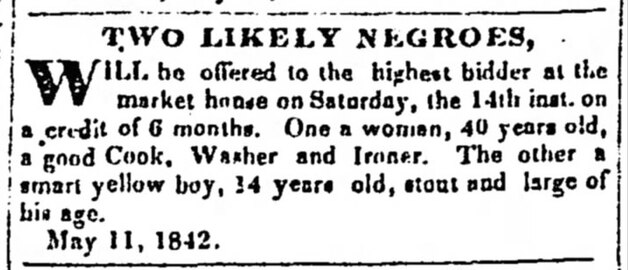

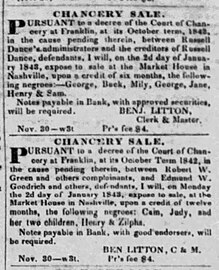

Newspaper clippings of the building

[edit]-

10 human beings, young

-

"and three other children"

-

Eliza and her increase

-

Woman, 40; boy, 14

-

"Terms, one half cash, balance notes payable in Bank at 6 months with two approved securities. The Negroes can be seen upon application to me."

-

20–30 human beings, of different ages

-

Matthew, Sylva, Hannah, Hester, Susan, Louisa, Elizabeth, Matthew, Robert, also a female child of Sylva's about 18 months old

-

George, Buck, Mily, George, Jane, Henry, Sam, Cain, Judy, Henry, Zilpha

-

John, Jim, Harriet, Tamor, Rachel, Mary

-

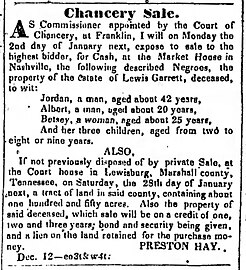

Jordan, Albert, Betsey, three children aged from two to nine years

-

Dicey, John Santon, Sandy, Caroline, Julina

Cherry & Cedar

[edit]The Memphis Avalanche reported in 1888 that Nashville's old slave mart was to be demolished soon:[8]

A LANDMARK GOING The Old Slave Mart of Nashville to Be Demolished Special Dispatch to the Avalanche Nashville March 5 Workmen today began the demolition of probably the most historic building in Nashville—that known as the Old Slave Mart on the southwest corner of Cherry and Cedar streets—in order to begin the erection of a large block which will comprise a hotel stores and offices. The buildings extend from the old Freedman's Bank Building on Cedar street to the corner of Cherry street and thence up Cherry to the alley. This block is an old landmark having been erected way back in the thirties. Since the war the corner has not bore the best reputation as several very serious affrays have occurred there and at times a portion of the block was used as a dive by rough characters. Many a raid has been made by the officers on the dens located in the block. The block is historic because used as a slave mart before the war. In the rear of the building there is a high brick wall enclosing a court where the slaves used to exercise and were exhibited to purchasers. The iron bars are still on some of the doors and the windows bear evidence of the character of the building The main auction room opened out on Cedar street. This however has been divided up into small stores. There was in olden times two other slave marts between Cherry street and the public square. These have been torn away and all evidence of it destroyed. The other one was on the corner of Cherry and Deaderick streets and the high wall that surrounded the corner now stands.

Accounts in slave narratives

[edit]The subject of one slave narrative interview conducted by Fisk University staff in the 1920s stated, "There was a sale block where they carried the Negroes there and auctioned them off. Right where that old building is now, those Irishmen got rich selling Negroes to white folks."[9] Another man told the interviewer that he had been sold four times in his life and recalled of the slave markets, "You could see the women crying about their babies and children they had left."[9] A third recalled that her mother was sold in Nashville, to buyers who lived in another state.[10] A centenarian named Millie Simpkins interviewed by the WPA Slave Narratives project told her experience:[10]

"My first mistress sold me because I was stubborn. She sent me to the 'slave yard' at Nashville. The yard was full of slaves. I stayed there two weeks before Master Simpson bought me. I was sold away from my husband and I never saw him again. I had one child which I took with me...The slave yard was on Cedar Street...A Mr. Chandler would bid the slaves off, but before they started bidding you had to take all of your clothes off and roll down the hill so they could see that you didn't have no bones broken, or sores on you. (I wouldn't take mine off.) If nobody bid on you, you was took to the slave mart and sold. I was sold here. A bunch of them was sent to Mississippi and they had their ankles fastened together and they had to walk while the traders rode.

See also

[edit]- Slave markets and slave jails in the United States

- Slave trade in the United States

- Andrew Jackson and the slave trade in the United States

- History of Nashville

References

[edit]- ^ Lovett, Bobby L. (1999). The African-american History of Nashville, Tn: 1780-1930 (p). University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-61075-412-5.

- ^ Goetsch, Elizabeth K. (2018-10-15). Lost Nashville. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-6556-5.

- ^ Lovett, Bobby L. (1999). The African-american History of Nashville, Tn: 1780-1930 (p). University of Arkansas Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-61075-412-5.

- ^ Davenport, Bishop (1842). A history and new gazetteer, or geographical dictionary, of North America and the West Indies. S.W. Benedict. pp. 434–435.

- ^ Goetsch, Elizabeth K. (2018-10-15). Lost Nashville. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-6556-5.

- ^ Wooldridge, John; Reese, W. B.; Hoss, Elijah Embree (1970) [1890]. History of Nashville, Tennessee. Nashville, Tenn.: Published for H. W. Crew by the Pub. House of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. p. 116.

- ^ Robert, Charles Edwin (1870). Nashville and her trade for 1870: a work containing information valuable alike to merchants, manufacturers, mechanics, emigrants and capitalists ... Nashville: Printed by Roberts & Purvis. pp. 371–372 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "A Landmark Going: The Old Slave Mart of Nashville to Be Demolished". Memphis Avalanche. 1888-03-06. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ a b Carey, Bill (2018-02-02). "Life in Slavery". The Tennessee Magazine. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ a b Harrison, Lowell H. (1974). "Recollections of Some Tennessee Slaves". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 33 (2): 175–190. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42623449.

External links

[edit]