The Sun (New York City)

| It Shines for All | |

The November 26, 1834, front page of The Sun | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid[1] |

| Owner(s) | Moses Yale (1835) Frank Munsey (1916) |

| Editor | Benjamin Day (1833) |

| Founded | 1833 |

| Ceased publication | January 4, 1950 |

| Relaunched | The New York Sun (2002) |

| Headquarters | Sun Building, Park Row 150 Nassau Street The Sun Building |

The Sun was a New York newspaper published from 1833 until 1950. It was considered a serious paper,[2] like the city's two more successful broadsheets, The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune. The Sun was the first successful penny daily newspaper in the United States, and was for a time, the most successful newspaper in America.[3][4]

The paper had a central focus on crime news, in which it was a pioneer, and was the first journal to hire a police reporter.[5][6] Its audience was primarily working class readers.

The Sun is well-known for publishing the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, as well as Francis Pharcellus Church's 1897 editorial containing the line "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus".

It merged with the New York World-Telegram in 1950.

History

[edit]

The Sun began publication in New York on September 3, 1833, as a morning newspaper edited by Benjamin Day (1810–1889), with the slogan "It Shines for All".[7] It cost only one penny (equivalent to 32¢ in 2023[8]), was easy to carry, and had illustrations and crime reporting popular with working-class readers.[9]

It inspired a new genre across the nation, known as the penny press, which made the news more accessible to low-income readers at a time when most papers cost five cents.[1] The Sun was also the first newspaper to hire newspaper hawkers to sell it on the street, developing the trade of newsboys shouting headlines.[10]

The Sun was the first newspaper to report crimes and personal events such as suicides, deaths, and divorces. The paper had a focus on police reports and human-interest stories for the masses, which consisted of short descriptions of arrests, thefts, and violence.[12][4] With their competitor the New York Herald, founded by James Gordon Bennett, they covered murder cases such as Helen Jewett's murder, the murder of John C. Colt's murder, Samuel Colt's brother, and Mary Rogers's case near Sybil's Cave.[13][14] The Sun and The Herald took sides in these cases, championing working class people over the traditional landed and mercantile elites which, during this era, held disproportionate power over the nation's politics and economy.[14]

Benjamin Day's brother-in-law, Moses Yale Beach, joined the venture in 1834, became co-owner in 1835, and a few years later, became sole proprietor, bringing a number of innovations to the industry.[15] It became the largest among the Gotham papers for 20 years, sometimes eclipsed by the New-York Tribune or the New York Herald.[16][17]

The newspaper printed the first newspaper account of a suicide. This story was significant because it was the first about the death of an ordinary person. It changed journalism forever, making the newspaper an integral part of the community and the lives of the readers.[citation needed]

Day was the first to hire reporters to go out and collect stories. Prior to this, newspapers dealt almost exclusively in articles about politics or reviews of books or the theater and relied, in the days before the organization of syndicates such as the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI), on items sent in by readers and unauthorized copies of stories from other newspapers. The Sun's focus on crime was the beginning of "the craft of reporting and storytelling".[18][19]

Crime news provided New Yorkers with information about how the city worked, dwelling on violations of justice, abuse of state power and corrupt schemes.[20]

The Sun was also the first newspaper to show that a newspaper could be substantially supported by advertisements rather than subscription fees, and could be sold on the street instead of delivered to each subscriber. Prior to The Sun, printers produced newspapers, often at a loss, making their living selling printing services.[21] Day and The Sun recognized that the masses were fast becoming literate, and demonstrated that a profit could be made selling to them.

The offices of The Sun were initially located on Printing House Square, now called Park Row, Manhattan, and was next to New York City Hall and New York City Police Department. It had a pigeon house built on the roof of its New York office at Nassau Street, receiving news from New York Harbor.[22] They also later used horses, steamships, trains, and the telegraph, the Pony Express and Royal Mail Ships.

Later history

[edit]

Moses Yale Beach's sons, Alfred Ely Beach and Moses S. Beach, took over the paper following his retirement. He celebrated the event at his house on Chambers Street, along with the other editors of Gotham, with guests including Congressmen Horace Greeley and James Brooks, and Abraham Lincoln's Chairman Henry Jarvis Raymond.[23][24]

In 1868, Moses S. Beach sold the newspaper to Charles A. Dana, the Assistant Secretary of War of Abraham Lincoln, and stayed a stockholder.[25][26][27] In 1872 The Sun exposed the Crédit Mobilier Scandal, implicating a number of corrupt Congressmen and Vice President Schuyler Colfax in a corrupt scheme involving the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, and in 1881 exposed the Star Route Scandal, implicating a number of high-profile politicians and businessmen in a scheme relating to the US Postal Service, resulting in number of trials and increasing public support for civil service reform.[28][29]

An evening edition, known as The Evening Sun, was introduced in 1887. The newspaper magnate Frank Munsey bought both editions of the paper in 1916 and merged The Evening Sun with his New York Press. The morning edition of The Sun was merged for a time with Munsey's New York Herald as The Sun and New York Herald, but in 1920, Munsey separated them again, killed The Evening Sun, and switched The Sun to an evening publishing format.[7]

From 1914 to 1919, The Sun moved its offices to 150 Nassau Street, one of the first skyscrapers made of steel, and one of the tallest in the city at the time. The tower was close to the New York Times Building, Woolworth Tower, and New York City Hall. In 1919, The Sun moved its offices to the A.T. Stewart Company Building, site of America's first department store, at 280 Broadway between Reade and Chambers Streets.[30] 280 Broadway was renamed "The Sun Building" in 1928.[30][31] A clock featuring The Sun's name and slogan was built at the corner with Broadway and Chambers Street.[32]

Munsey died in 1925 with a fortune of about 20 million dollars, and was ranked as one of the most powerful media moguls of his time, along with William Randolph Hearst.[33] He left the bulk of his estate, including The Sun, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The next year The Sun was sold to William Dewart, a longtime associate of Munsey's. Dewart's son Thomas later ran the paper.[34]

In the 1940s, the newspaper was considered among the most conservative in New York City and was strongly opposed to the New Deal and labor unions. The Sun won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949 for an exposé of labor racketeering; it also published the early work of sportswriter W.C. Heinz.

It continued until January 4, 1950, when it merged with the New York World-Telegram to form a new paper called the New York World-Telegram and Sun. That paper continued for 16 years; in 1966, it joined with the New York Herald Tribune to briefly become part of the World Journal Tribune, preserving the names of three of the most historic city newspapers, which folded amid disputes with the unions representing its staff the following year.

Milestones

[edit]

The Sun first gained notice for its central role in the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, a fabricated story of life and civilization on the Moon which the paper falsely attributed to British astronomer John Herschel and never retracted.[35] The hoax featured man-bat creatures named the "Vespertilio-homo" that inhabited the moon and built temples. A Yale University delegation was sent to look after the article, and the whole story created much sensation at the time.[19]

On April 13, 1844, The Sun published a story by Edgar Allan Poe now known as "The Balloon-Hoax", retracted two days after publication. The story told of an imagined Atlantic crossing by hot-air balloon.[36]

Today the paper is best known for the 1897 editorial "Is There a Santa Claus?" (commonly referred to as "Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus"), written by Francis Pharcellus Church.[37]

John B. Bogart, city editor of The Sun between 1873 and 1890, made what is perhaps the most frequently quoted definition of the journalistic endeavor: "When a dog bites a man, that is not news, because it happens so often. But if a man bites a dog, that is news."[38] (The quotation is frequently attributed to Charles Dana, The Sun editor and part-owner between 1868 and his death in 1897.)

From 1912, Don Marquis wrote a regular column, 'The Sundial', for the Evening Sun. In 1916, he used this to introduce his characters Archy and Mehitabel.[39]

In 1926, The Sun published a review by John Grierson of Robert Flaherty's film Moana, in which Grierson said the film had "documentary value". This is considered the origin of the term "documentary film".[40]

The newspaper's editorial cartoonist, Rube Goldberg, received the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning for his cartoon, Peace Today. In 1949, The Sun won the Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting for a groundbreaking series of articles by Malcolm Johnson, "Crime on the Waterfront". The series served as the basis for the 1954 movie On the Waterfront.

The Sun's first female reporter was Emily Verdery Bettey, hired in 1868. Eleanor Hoyt Brainerd was hired as a reporter and fashion editor in the 1880s. Brainerd was one of the first women to become a professional editor, and perhaps the first full-time fashion editor in American newspaper history.

In 1881, the heroic legend of sheriff Bartholomew Masterson, known as "Bat Masterson", started from the coverage of a Sun reporter whom he had duped.[41] He was a companion of Buffalo Bill, and fought at the Battle of Dodge City War, and was later the subject of a book titled Gunfighter in Gotham and the American TV series Bat Masterson.[41]

-

Louis Brandeis, political cartoon, January 31, 1916

-

Representative journals, competitor James Gordon Bennett, 1882

-

Charles A. Dana, from the American Editors series, 1887

Legacy

[edit]

The film Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) is a story about the death of a New York newspaper called The Day, loosely based upon the Sun, which closed in 1950. The original Sun newspaper was edited by Benjamin Day, making the film's newspaper name a play on words (not to be confused with the real-life New London, Connecticut newspaper of the same name).

The masthead of the original Sun is visible in a montage of newspaper clippings in a scene of the 1972 film The Godfather. The newspaper's offices were a converted department store at 280 Broadway, between Chambers and Reade streets in lower Manhattan, now known as "The Sun Building" and famous for the clocks that bear the newspaper's masthead and motto. They were recognized as a New York City landmark in 1986. The building now houses the New York City Department of Buildings.

In the 1994 movie The Paper, a fictional tabloid newspaper based in New York City bore the same name and motto of The Sun, with a slightly different masthead.

In 2002, a new broadsheet was launched, styled The New York Sun, and bearing the old newspaper's masthead and motto. It was intended as a "conservative alternative" and local news-focused alternative to the more liberal The New York Times and other New York newspapers. It was published by Ronald Weintraub and edited by Seth Lipsky, and ceased publication on September 30, 2008. In 2022, it was revived as an online newspaper, under the ownership of Dovid Efune, while Lipsky remained editor.[43]

The history of the New York Sun is extensively covered in the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.[44] Past reporters of the paper have included NYC Police Commissioner, Col. Arthur H. Woods, and NYC Fire Commissioner Robert Adamson.[45]

Journalists at The Sun

[edit]

- John A. Arneaux, reporter in 1884

- Moses Yale Beach, an early owner of the Sun

- Charles Anderson Dana, editor and part-owner of the Sun

- Paul Dana, editor, 1880–1897

- W. C. Heinz, war correspondent, sportswriter 1937–1950

- Bruno Lessing, reporter, 1888–1894

- Chester Sanders Lord, journalist and managing editor,[46] 1873-1913

- Kenneth M. Swezey, radio/technology reporter, 1930s

- John Swinton, chief editorialist, 1875–1883 and 1892–1897

Gallery

[edit]-

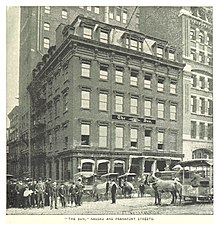

The Sun offices between 1914 and 1919 at 150 Nassau Street

-

Newspaper Row, New York City; the Sun on the left

-

View of The Sun Building name on Broadway

-

The "Sun Building" at 280 Broadway, from 1919 to 1950

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rogers, Tony (March 17, 2017). "What's the Difference Between Broadsheet and Tabloid Newspapers?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "Obituary of Charles Anderson Dana". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 27, 1897. p. 4. ISSN 2379-7304. Retrieved July 14, 2020 – via National Endowment for the Humanities.

- ^ Wm. David Sloan (1979). "George W. Wisner: Michigan Editor and Politican [sic]". Journalism History. 6 (4): 113–116. doi:10.1080/00947679.1979.12066929. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ a b The Sun (New York, N.Y.) 1833-1916, New York Sun / Extra sun / Issues for Apr. 13-Sept. 28, 1840

- ^ "New York Sun, American newspaper". Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Benjamin Henry Day, American journalist and publisher". Encyclopaedia Britannica. September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Sun's Centary". Time. September 11, 1933. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Macmillan Highered, The Evolution of American Newspapers, Day and the New York Sun, p. 271

- ^ Pre-Civil War American Culture, The Birth of American Popular Culture, University of Houston. Digital History ID 3555

- ^ O'Brien, Frank Michael. The Story of the Sun: New York, 1833–1918. New York: George H. Doran Co, 1918. p. 229

- ^ Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication, Newspapers as a Form of Mass Media; The Penny Press, Libraries Publishing

- ^ Deeds of Death, and Blood': The Introduction of Sensational Crime Reporting into Nineteenth Century Penny Press, p. 78-81

- ^ a b "The Best Side of a Case of Crime": George Lippard, Walt Whitman, and Antebellum Police Reports, January 2011, American Periodicals A Journal of History Criticism and Bibliography 21 (2)

- ^ Moses Yale Beach, An American inventor and newspaper entrepreneur, Moses Yale Beach (1800-1868) contributed to the technology of his time but was, above all, an important developer of popular journalism, Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Lee, James Melvin (1917). STEAM EXPEESSES OF " THE SUN, History of American Journalism, Houghton Mifflin Company, Director of the Department of Journalism New York University, Chapter 9, p. 212

- ^ Luther Molt, Frank (1942). American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 Years, 1690 to 1940, The Macmillan Company, New York, p. 222-227

- ^ Luther Molt, Frank (1942). American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 Years, 1690 to 1940, The Macmillan Company, New York, p. 224

- ^ a b Maury Klein (1996). When New York Became the U.S. Media Capital, City Journal, From the Magazine Technology and Innovation, States and Cities, Economy, finance, and budgets, Arts and Culture, Summer 1996

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. (1999) Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, p. 524

- ^ Spencer, David R.; Overholser, Geneva (January 23, 2007). The Yellow Journalism: The Press and America's Emergence as a World Power. Medill Vision of the American Press. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. pp. 22–28. ISBN 978-0-8101-2331-1.

- ^ Benson John Lossing (1884).History of New York City: Embracing an Outline Sketch of Events, Volume 1., The Perine Engraving And Publishing Co., New York, p. 362-363

- ^ A. Gray, John (1859). The Knickerbocker, New-York Monthly Magazine, Volume 54, 16 & 18 Jacob Street, p. 210

- ^ The Story of the Sun. New York, 1833-1918, Chapter VIII “The Sun” During The Civil War

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission, October 7, 1986, p. 13

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 791–792.

- ^ The Story of the Sun, New York, 1833-1918, Frank M. O'Brien, George H. Doran Co, New York, 1918, Chapter VIII : The Sun During the Civil War

- ^ Redbook magazine, Wild Political Scandals From the 19th Century, The Crédit Mobilier Scandal, Colin Scanlon, Mar 27, 2023, slide 3

- ^ Redbook magazine, Wild Political Scandals From the 19th Century, The Star Route Scandal, Colin Scanlon, Mar 27, 2023, slide 6

- ^ a b "New York Sun Buys Building: Acquires Structure Used by A.T. Stewart". Daily Boston Globe. January 3, 1928. p. 6. ProQuest 747438326.

- ^ "Stewart Building is Sold to the Sun; Newspaper Obtains Home From Metropolitan Museum, Legatee of Frank A. Munsey". The New York Times. January 3, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 23, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Group Acts to Save The Sun Clock". The New York Times. August 30, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ The Sun Building, Landmarks Preservation Camnission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1439

- ^ "Thomas Dewart, 90; Publisher of the Sun". The New York Times. September 5, 2001.

- ^ Washam, Erik, "Cosmic Errors: Martians Build Canals!" Archived September 12, 2012, at archive.today, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9. p. 410

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph. 110 Years Ago in News History: 'Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus' Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. American University. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 16th edition, ed. Justin Kaplan (Boston, London, and Toronto: Little, Brown, 1992), p. 554.

- ^ Don Marquis entry in SFE: The Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction

- ^ Barsam, Richard (1992). Non-Fiction Film: A Critical History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20706-7.

- ^ a b Gunfighter in Gotham: Bat Masterson's New York City Years, by Robert K. De Arment, 2013

- ^ The story of the Sun, New York: 1833-1928, O'Brien, Frank Michael, 1875

- ^ Robertson, Katie (November 3, 2021). "The New York Sun, a defunct newspaper, plans a comeback after a sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. (1999) Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Oxford University Press, p. 523-525-527-640-677-684-700-706-932

- ^ The Story of the Sun: New York, 1833-1918, Frank Michael O'Brien

- ^ The Young Man and Journalism, McGraw Hill, 1922.

Further reading

[edit]- Lancaster, Paul. Gentleman of the Press: The Life and Times of an Early Reporter, Julian Ralph of the Sun. Syracuse University Press; 1992.

- O'Brien, Frank Michael. The Story of The Sun: New York, 1833–1918 (1918) (page images and OCR)

- Steele, Janet E. The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana (Syracuse University Press, 1993)

- Stone, Candace. Dana and the Sun (Dodd, Mead, 1938)

- Tucher, Andie, Froth and Scum: Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and the Ax Murder in America's First Mass Medium'. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

External links

[edit]- The Sun digitized at Chronicling America, Library of Congress (1859 to 1916, incomplete)

![New York Harbor, receiving news from Europe, Great Western, 1838[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/Great_Western_and_New_York_in_New_York_Harbor%2C_April_23%2C_1838.jpg/140px-Great_Western_and_New_York_in_New_York_Harbor%2C_April_23%2C_1838.jpg)