Peter Francisco

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Peter Francisco | |

|---|---|

Miniature portrait, early 19th century | |

| Born | Pedro Francisco July 9, 1760 |

| Died | January 16, 1831 (aged 70) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Shockoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Other names | Virginia Giant, Giant of the Revolution, Virginia Hercules |

| Occupation(s) | Blacksmith, soldier, sergeant-at-arm |

| Height | 6 ft 8 in (203 cm) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 son with Susannah Anderson 2 sons and 2 daughters with Catherine Fauntleroy Brooke |

Peter Francisco (born Pedro Francisco; July 9, 1760 – January 16, 1831), known variously as the "India", the "Giant of the Revolution", and occasionally the "Virginia Hercules", was a Portuguese-born American patriot and soldier in the American Revolutionary War.

Early life[edit]

Francisco's early years are shrouded in mystery. It is believed he was born on July 9, 1760, at Porto Judeu, on the island of Terceira, in the Archipelago of the Azores, Portugal. In the case of the origin of his identification with the child named Pedro Francisco, his parents, Luiz Francisco Machado and Antónia Maria, natives of mainland Portugal (then an empire under the government of the Marquis of Pombal), a relatively wealthy and noble family, settled on the Island of Terceira (where he was born), distancing themselves more from personal or political enemies in the continent.[clarification needed] According to the traditional version of his biography,[1] he was found at about age five on the docks at City Point, Virginia, in 1765, and was taken to the Prince George County Poorhouse. Not speaking English, he repeated the name "Pedro Francisco". The locals called him Peter. They soon discovered the boy spoke Portuguese and noted his clothing was of good quality.

When able to communicate, Pedro said that he had lived in a mansion near the ocean. His mother spoke French and his father spoke another language that he did not know. He and his sister were kidnapped from the grounds, but his sister escaped, while Francisco was bound and taken to a ship. Historians believe it is possible that the kidnappers intended to hold the children for ransom or that they had intended to sell them as indentured servants at their destination port in North America, but changed their minds. The Azorean legend says the Francisco family had many political enemies and set up Peter's abduction to protect him from accident or death by his parents' foes.

Peter was taken in by the judge Anthony Winston of Buckingham County, Virginia, an uncle of Patrick Henry's. Francisco lived with Winston and his family until the beginning of the American Revolution and was tutored by them. When he was old enough to work, he was apprenticed as a blacksmith, a profession chosen because of his massive size and strength (he grew to be six feet and eight inches in height, or 203 centimeters, and weigh some 260 pounds, or 118 kilograms, especially large at the time). It was also noted that his hair may have turned silver at an early age. He was well known as the Virginian Hercules or the Virginia Giant.

American Revolutionary War[edit]

At the age of 16, Francisco joined the 10th Virginia Regiment in 1776 and soon gained notoriety for his size and strength. He fought with distinction at numerous engagements, including the Battle of Brandywine in September. He fought a few skirmishes under Colonel Daniel Morgan, before transferring to the regiment of Colonel John Mayo of Powhatan. In October, Francisco rejoined his regiment and fought in the Battle of Germantown, and also appeared with the troops at Fort Mifflin on Port Island in the Delaware River. Francisco was hospitalized at Valley Forge for two weeks following these skirmishes. On June 28, 1778, he fought at Monmouth Court House, New Jersey, where a musket ball tore through his right thigh. He never fully recovered from this wound, but fought at Cowpens and other battles.

Francisco was part of General "Mad" Anthony Wayne's attack on the British fort of Stony Point on the Hudson River. Upon attacking the fort, Francisco suffered a nine-inch gash in his stomach, but continued to fight; he was second to enter the fort. He killed twelve British grenadiers and captured the enemy flag. Francisco's entry into the fort is mentioned in Wayne's report on the battle to General Washington, dated July 17, 1779, and in a letter written by Captain William Evans to accompany Francisco's letter to the Virginia General Assembly in November 1820 for pay. As a result of being the second man to enter the fort, he received 200 dollars.[2]

Following the Battle of Camden, South Carolina, Francisco noticed the Americans were leaving behind one of their valuable cannons, mired in mud. Legend says he freed and picked up the approximately 1,100-pound cannon and carried it on his shoulder to keep it from falling into the hands of the enemy. In a letter Francisco wrote to the Virginia General Assembly on November 11, 1820, he said that at Camden, he had shot a grenadier who had tried to shoot Colonel Mayo. He escaped by bayoneting one of Banastre Tarleton's cavalrymen and fled on the horse making cries to make the British think he was a Loyalist. The horse was later given to Mayo.[3]

Hearing that Colonel William Washington was headed on a march through the Carolinas, Francisco joined him, seeing action at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina. He allegedly killed eleven men on the field of battle, including one who wounded him severely in the thigh with a bayonet.[4] In his own words, Francisco was "seen to kill two men, besides making many other panes [sic] which were doubtless fatal to others."[3] The feat is commemorated with a monument to Francisco at the National Military Park.[4]

Legend of Francisco's Fight[edit]

Francisco was sent home to Buckingham, Virginia to recuperate. He volunteered to spy on Tarleton and his horsemen, who were operating in the area. On this journey, he performed his best-known action: Francisco's Fight. He claimed to have defeated a detachment of Tarleton's British Legion soldiers and escaped with their horses. Legend has it that he killed or mortally wounded three of the eleven soldiers. One night, nine of Tarleton's men surrounded Francisco outside of a tavern and ordered him to be arrested. They told him to give over his silver shoe buckles. Francisco told Tarleton's men to take the buckles themselves. When they began to seize his shoe buckles, Francisco took a soldier's saber and struck him on the head. The wounded soldier fired his pistol, grazing Francisco's side; Francisco nearly cut off the soldier's hand. Another enemy soldier aimed a musket at Francisco, but the musket misfired. Francisco grabbed it from the soldier's hands, knocked him off his mount, and escaped with the horse.[5]

However, in his 1820 letter to the Virginia legislature, Francisco reported having killed one and wounded eight of the nine soldiers, and captured eight of their nine horses.[3] In a brief 1829 petition to the United States Congress, he claimed to have dispatched or killed three British Legion soldiers and frightened the other six away while capturing eight of their horses.[6] Francisco was ordered by his commanding officer to join the army in 1781 at Yorktown; he did not fight but was a witness to the British surrender.

Later years[edit]

Following Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, Francisco pursued his basic education. He went to school with young children, who were fascinated by his stories of the war. Legends of Francisco's strength abounded during his lifetime.[4]

Marriage and family[edit]

In December 1784, Peter married Susannah Anderson of Cumberland County, Virginia. She was the daughter of Captain James Anderson and his wife Elizabeth Tyler Baker Anderson. The Andersons were of social distinction and owned a plantation called "The Mansion." Peter and Susannah had two children: a son, James Anderson, born in the log house in 1786; and a daughter, Polly, born in 1788. Peter sold the 250 acres on Louse Creek in 1788. His wife Susannah died in 1790 of dysentery. In December 1794, Peter married Catherine Fauntleroy Brooke, who was a relative of his first wife's, and they moved to Peter's home in Cumberland. Peter and Catherine had four children: Susan Brooke Francisco (born 1796), Benjamin M. Francisco (born 1803), Peter II, and Catherine Fauntleroy Francisco. His second wife died in 1821, and he married for the third time, in July 1823, this time to Mary Grymes West.

Death[edit]

In his later years, Francisco was poor and had petitioned Congress and the Virginia legislature for a pension.[3][6] He spent the last three years of his life working as the Sergeant-at-Arms to the Virginia State Senate. He died of appendicitis, on January 16, 1831, and was buried with full military honors in Shockoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond. The Virginia state legislature adjourned for the day, and many legislators attended his funeral.[4]

Legacy and honors[edit]

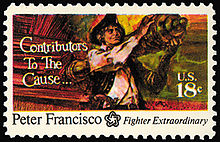

- 1975, Francisco was commemorated on a stamp by the US Postal Service in its "Contributors to the Cause" Bicentennial series. The image shows his saving the cannon at Camden.

- Peter Francisco Park in the Ironbound section of Newark, New Jersey, where most of the population is ethnic Portuguese, is named for him. The community also erected a monument to Francisco there.

- His farmhouse, Locust Grove, still stands outside the town of Dillwyn, in Buckingham County.

- The town of Francisco in Stokes County, North Carolina is named for him.

- Legend has it that General Washington commissioned a special six-foot broadsword to match Francisco's size. Some years after his death, that famous sword was presented by his daughter, Mrs. Edward Pescud of Petersburg, Va., to the Virginia Historical Society. However, the weapon has since disappeared.

- One of his swords, though not the broadsword commissioned for him by Washington, is displayed in the Buckingham County Historical Museum.

- Peter Francisco Square, marked by a monument honoring his life and service, was named at the corner of Hill Street and Mill Street in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which has a large ethnic Portuguese community. The monument includes a Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) medallion of honor.

- A small stone monument dedicated to Peter Francisco and all Portuguese-American veterans is located on the property of the Hudson Portuguese Club in Hudson, Massachusetts.

- Peter Francisco Day is officially recognized on March 15 (anniversary of the Battle of Guilford Court House) in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Virginia,[7][8] while Maryland has also honored him on this day.[9]

- The Portuguese Continental Union, a U.S.-based fraternal benefit society, bestows the Peter Francisco Award on individuals or institutions who bring prestige to people of Portuguese heritage in the United States and to the Portuguese language and culture.

- A statue of Peter as a young boy stands in his birthplace of Porto Judeu, Terceira, dedicated in 2015 on the 250th anniversary of his arrival in America.[10]

- A monument commemorating the life of Peter Francisco is located on the grounds of the municipal building in Hopewell, Va. The City of Hopewell (formerly City Point) is believed to be the location where young Peter was found abandoned on the docks as a child. The city of Hopewell has also named a street in his honor – "Peter Francisco Drive".

- His great-great-grandson, Steven Pruitt, created this article to commemorate him.[11]

In popular culture[edit]

- Namesake of the fiddle tune "Peter Francisco"[12]

- Namesake of a folk song recorded by Jimmie Driftwood. The song tells a tall tale bearing little resemblance to Francisco's actual biography.

- Namesake of a folk song recorded by Danny O'Flaherty. This song attempts to tell a more accurate story of his life.

- Central figure in the 1956 young adult novel Sword of Francisco by Charles Wilson[13]

- Central figure in the 2015 novel Luso: For Love, Liberty, and Legacy by Travis Bowman.[14]

- The seventh episode of the first season of the History Channel television show The Strongest Man In History has the show's four professional strongmen, Eddie Hall, Nick Best, Robert Oberst, and Brian Shaw, recounting and recreating several of Francisco's legendary feats of strength. [15]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Other versions hold that Francisco was taken to Ireland; as a youth, he became indentured to a sea captain and traveled with him to City Point. Found abandoned, he was put in the poorhouse until taken in by Judge Winston. This version does not support the generally accepted dates given for Francisco's birth and transport; it is considered a legend.

- ^ Thompson, Ben (2017). Guts & Glory: The American Revolution (First ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company, Hachette Book Group. pp. 206, 216. ISBN 978-0316312097.

- ^ a b c d Mary, College of William & (1905). William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. Institute of Early American History and Culture.

- ^ a b c d "Peter Francisco". American Battlefield Trust. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Howe, Henry (1852) [1845]. Historical Collections of Virginia: Containing a Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to its History and Antiquities Together with Geographical and Statistical Descriptions : to Which is Appended an Historical and Descriptive Sketch of the District of Columbia. Charleston, SC: Babcock & Co. ISBN 9780722209158. OCLC 416295361. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Niles, H, ed. (1829). Niles' National Register, Volume 35. Baltimore, MD: H. Niles. OCLC 4765078. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Peter Francisco, Giant of the American Revolution

- ^ "Peter Francisco: American Revolutionary War Hero". July 25, 2006. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Peter Francisco Day". Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Dedication of Statue of Peter Francisco" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Yassin, Nuseir. "The Secret King of Wikipedia". YouTube. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ ""Peter Francisco" at the Traditional Tune Archive". Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Charles George Wilson, Sword of Francisco, illustrated by Ray Campbell; New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1956. OCLC 1729511

- ^ Bowman, Travis (2015). Luso: For Love, Liberty, and Legacy. Independent Publisher. ISBN 978-1495170461.

- ^ "Revolutionary Strongmen". IMDb.

External links[edit]

- Peter Francisco: Remarkable American Revolutionary War Soldier

- Peter Francisco, Library of Congress

- Society of the Descendants of Peter Francisco

- The Peter Francisco Story on YouTube

- Transcript of Peter Francisco's 11 November 1820 petition {reference only}

- Hercules of the Revolution Archived July 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Archived

- Peter Francisco's Birth Record

- Peter Francisco Day, Virginia Historical Society

- Peter Francisco, Patriot of Virginia

- 1760 births

- 1831 deaths

- American people of Azorean descent

- American people of Portuguese descent

- American folklore

- Continental Army soldiers

- Deaths from appendicitis

- Immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies

- People from Angra do Heroísmo

- People from Buckingham County, Virginia

- People of Virginia in the American Revolution

- Portuguese emigrants to the United States

- Tall tales