Epistemology

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. It studies the nature, origin, and scope of knowledge, epistemic justification, and various related issues. Debates in contemporary epistemology are generally clustered around four core areas:[1][2][3]

- The philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, such as truth and justification;

- Potential sources of knowledge and justified belief, such as perception, reason, memory, and testimony

- The structure of a body of knowledge or justified belief, including whether all justified beliefs must be derived from justified foundational beliefs or whether justification requires only a coherent set of beliefs; and,

- Philosophical scepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge, and related problems, such as whether scepticism poses a threat to our ordinary knowledge claims and whether it is possible to refute sceptical arguments.

In these debates and others, epistemology aims to answer questions such as "What do people know?", "What does it mean to say that people know something?", "What makes justified beliefs justified?", and "How do people know that they know?"[4][1][5][6] Specialties in epistemology ask questions such as "How can people create formal models about issues related to knowledge?" (in formal epistemology), "What are the historical conditions of changes in different kinds of knowledge?" (in historical epistemology), "What are the methods, aims, and subject matter of epistemological inquiry?" (in metaepistemology), and "How do people know together?" (in social epistemology).

Definition

[edit]Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge. Also called theory of knowledge,[note 1] it examines what knowledge is and what types of knowledge there are. It further investigates the sources of knowledge, like perception, inference, and testimony, to determine how knowledge is created. Another topic is the extent and limits of knowledge, confronting questions about what people can and cannot know.[8] Other central concepts include belief, truth, justification, evidence, and reason.[9] Epistemology is one of the main branches of philosophy besides fields like ethics, logic, and metaphysics.[10] The term can also be used in a slightly different sense to refer not to the branch of philosophy but to a particular position within that branch, as in Plato's epistemology and Immanuel Kant's epistemology.[11]

As a normative field of inquiry, epistemology explores how people should acquire beliefs. This way, it determines which beliefs fulfill the standards or epistemic goals of knowledge and which ones fail, thereby providing an evaluation of beliefs. Descriptive fields of inquiry, like psychology and cognitive sociology, are also interested in beliefs and related cognitive processes. Unlike epistemology, they study the beliefs people have and how people acquire them instead of examining the evaluative norms of these processes.[12][note 2] Epistemology is relevant to many descriptive and normative disciplines, such as the other branches of philosophy and the sciences, by exploring the principles of how they may arrive at knowledge.[14]

The word epistemology comes from the ancient Greek terms ἐπιστήμη (episteme, meaning knowledge or understanding) and λόγος (logos, meaning study of or reason), literally, the study of knowledge. Even though ancient Greek philosophers practiced epistemology, they did not use this word. The term was only coined in the 19th century to label this field and conceive it as a distinct branch of philosophy.[15][note 3]

Central concepts

[edit]Knowledge

[edit]Knowledge is an awareness, familiarity, understanding, or skill. Its various forms all involve a cognitive success through which a person establishes epistemic contact with reality.[20] Knowledge is typically understood as an aspect of individuals, generally as a cognitive mental state that helps them understand, interpret, and interact with the world. While this core sense is of particular interest to epistemologists, the term also has other meanings. Understood on a social level, knowledge is a characteristic of a group of people that share ideas, understanding, or culture in general.[21] The term can also refer to information stored in documents, such as "knowledge housed in the library"[22] or knowledge stored in computers in the form of the knowledge base of an expert system.[23]

Knowledge contrasts with ignorance, which is often simply defined as the absence of knowledge. Knowledge is usually accompanied by ignorance since people rarely have complete knowledge of a field, forcing them to rely on incomplete or uncertain information when making decisions.[24] Even though many forms of ignorance can be mitigated through education and research, there are certain limits to human understanding that are responsible for inevitable ignorance.[25] Some limitations are inherent in the human cognitive faculties themselves, such as the inability to know facts too complex for the human mind to conceive.[26] Others depend on external circumstances when no access to the relevant information exists.[27]

Epistemologists disagree on how much people know, for example, whether fallible beliefs about everyday affairs can amount to knowledge or whether absolute certainty is required. The most stringent position is taken by radical skeptics, who argue that there is no knowledge at all.[28]

Types

[edit]

Epistemologists distinguish between different types of knowledge.[30] Their primary interest is in knowledge of facts, called propositional knowledge.[31] It is a theoretical knowledge that can be expressed in declarative sentences using a that-clause, like "Ravi knows that kangaroos hop". For this reason, it is also called knowledge-that.[32][note 4] Epistemologists often understand it as a relation between a knower and a known proposition, in the case above between the person Ravi and the proposition "kangaroos hop".[34] It is use-independent since it is not tied to one specific purpose. It is a mental representation that relies on concepts and ideas to depict reality.[35] Because of its theoretical nature, it is often held that only relatively sophisticated creatures, such as humans, possess propositional knowledge.[36]

Propositional knowledge contrasts with non-propositional knowledge in the form of knowledge-how and knowledge by acquaintance.[37] Knowledge-how is a practical ability or skill, like knowing how to read or how to prepare lasagna.[38] It is usually tied to a specific goal and not mastered in the abstract without concrete practice.[39] To know something by acquaintance means to be familiar with it as a result of experiental contact. Examples are knowing the city of Perth, knowing the taste of tsampa, and knowing Marta Vieira da Silva personally.[40]

Another influential distinction is between a posteriori and a priori knowledge.[41] A posteriori knowledge is knowledge of empirical facts based on sensory experience, like seeing that the sun is shining and smelling that a piece of meat has gone bad.[42] Knowledge belonging to the empirical science and knowledge of everyday affairs belongs to a posteriori knowledge. A priori knowledge is knowledge of non-empirical facts and does not depend on evidence from sensory experience. It belongs to fields such as mathematics and logic, like knowing that .[43] The contrast between a posteriori and a priori knowledge plays a central role in the debate between empiricists and rationalists on whether all knowledge depends on sensory experience.[44]

A closely related contrast is between analytic and synthetic truths. A sentence is analytically true if its truth depends only on the meaning of the words it uses. For instance, the sentence "all bachelors are unmarried" is analytically true because the word "bachelor" already includes the meaning "unmarried". A sentence is synthetically true if its truth depends on additional facts. For example, the sentence "snow is white" is synthetically true because its truth depends on the color of snow in addition to the meanings of the words snow and white. A priori knowledge is primarily associated with analytic sentences while a posteriori knowledge is primarily associated with synthetic sentences. However, it is controversial whether this is true for all cases. Some philosophers, such as Willard Van Orman Quine, reject the distinction, saying that there are no analytic truths.[46]

Analysis

[edit]The analysis of knowledge is the attempt to identify the essential components or conditions of all and only propositional knowledge states. According to the so-called traditional analysis,[note 5] knowledge has three components: it is a belief that is justified and true.[48] In the second half of the 20th century, this view was put into doubt by a series of thought experiments that aimed to show that some justified true beliefs do not amount to knowledge.[49] In one of them, a person is unaware of all the fake barns in their area. By coincidence, they stop in front of the only real barn and form a justified true belief that it is a real barn.[50] Many epistemologists agree that this is not knowledge because the justification is not directly relevant to the truth.[51] More specifically, this and similar counterexamples involve some form of epistemic luck, that is, a cognitive success that results from fortuitous circumstances rather than competence.[52]

Following these thought experiments, philosophers proposed various alternative definitions of knowledge by modifying or expanding the traditional analysis.[53] According to one view, the known fact has to cause the belief in the right way.[54] Another theory states that the belief is the product of a reliable belief formation process.[55] Further approaches require that the person would not have the belief if it was false,[56] that the belief is not inferred from a falsehood,[57] that the justification cannot be undermined,[58] or that the belief is infallible.[59] There is no consensus on which of the proposed modifications and reconceptualizations is correct.[60] Some philosophers, such as Timothy Williamson, reject the basic assumption underlying the analysis of knowledge by arguing that propositional knowledge is a unique state that cannot be dissected into simpler components.[61]

Value

[edit]The value of knowledge is the worth it holds by expanding understanding and guiding action. Knowledge can have instrumental value by helping a person achieve their goals.[62] For example, knowledge of a disease helps a doctor cure their patient, and knowledge of when a job interview starts helps a candidate arrive on time.[63] The usefulness of a known fact depends on the circumstances. Knowledge of some facts may have little to no uses, like memorizing random phone numbers from an outdated phone book.[64] Being able to assess the value of knowledge matters in choosing what information to acquire and transmit to others. It affects decisions like which subjects to teach at school and how to allocate funds to research projects.[65]

Of particular interest to epistemologists is the question of whether knowledge is more valuable than a mere opinion that is true.[66] Knowledge and true opinion often have a similar usefulness since both are accurate representations of reality. For example, if a person wants to go to Larissa, a true opinion about how to get there may help them in the same way as knowledge does.[67] Plato already considered this problem and suggested that knowledge is better because it is more stable.[68] Another suggestion focuses on practical reasoning. It proposes that people put more trust in knowledge than in mere true beliefs when drawing conclusions and deciding what to do.[69] A different response says that knowledge has intrinsic value, meaning that it is good in itself independent of its usefulness.[70]

Belief

[edit]One of the core concepts in epistemology is belief. A belief is an attitude that a person holds regarding anything that they take to be true.[71] For instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". Beliefs can be occurrent (e.g., a person actively thinking "snow is white"), or they can be dispositional (e.g., a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert "snow is white"). While there is not universal agreement about the nature of belief, most contemporary philosophers hold the view that a disposition to express belief B qualifies as holding the belief B.[71] There are various different ways that contemporary philosophers have tried to describe beliefs, including as representations of ways that the world could be (Jerry Fodor), as dispositions to act as if certain things are true (Roderick Chisholm), as interpretive schemes for making sense of someone's actions (Daniel Dennett and Donald Davidson), or as mental states that fill a particular function (Hilary Putnam).[71] Some have also attempted to offer significant revisions to the notion of belief, including eliminativists about belief who argue that there is no phenomenon in the natural world which corresponds to our folk psychological concept of belief (Paul Churchland) and formal epistemologists, who aim to replace our bivalent notion of belief ("either I have a belief or I don't have a belief") with the more permissive, probabilistic notion of credence ("there is an entire spectrum of degrees of belief, not a simple dichotomy between belief and non-belief").[71][72]

While belief plays a significant role in epistemological debates surrounding knowledge and justification, it has also generated many other philosophical debates in its own right. Notable debates include: "What is the rational way to revise one's beliefs when presented with various sorts of evidence?"; "Is the content of our beliefs entirely determined by our mental states, or do the relevant facts have any bearing on our beliefs (e.g., if I believe that I'm holding a glass of water, is the non-mental fact that water is H2O part of the content of that belief)?"; "How fine-grained or coarse-grained are our beliefs?"; and "Must it be possible for a belief to be expressible in language, or are there non-linguistic beliefs?"[71]

Truth

[edit]Truth is the property or state of being in accordance with facts or reality.[73] On most views, truth is the correspondence of language or thought to a mind-independent world. This is called the correspondence theory of truth. Among philosophers who think that it is possible to analyze the conditions necessary for knowledge, virtually all of them accept that truth is such a condition. There is much less agreement about the extent to which a knower must know why something is true in order to know. On such views, something being known implies that it is true. However, this should not be confused for the more contentious view that one must know that one knows in order to know (the KK principle).[1]

Epistemologists disagree about whether belief is the only truth-bearer. Other common suggestions for things that can bear the property of being true include propositions, sentences, thoughts, utterances, and judgments. Plato, in his Gorgias, argues that belief is the most commonly invoked truth-bearer.[74][clarification needed]

Many of the debates regarding truth are at the crossroads of epistemology and logic.[73] Some contemporary debates regarding truth include: How do we define truth? Is it even possible to give an informative definition of truth? What things are truth-bearers and therefore capable of being true or false? Are truth and falsity bivalent, or are there other truth values? What are the criteria of truth that allow us to identify it and to distinguish it from falsity? What role does truth play in constituting knowledge? And is truth absolute, or is it merely relative to one's perspective?[73]

Justification

[edit]In epistemology, justification is a property of beliefs that fulfill certain norms about what a person should believe.[75] According to a common view, this means that the person has sufficient reasons for holding this belief because they have information that supports it.[76] Another view states that a belief is justified if it is formed by a reliable belief formation process, such as perception.[77] The terms rational, reasonable, warranted, and supported are closely related to the idea of justification and are sometimes used as synonyms.[78] Justification is what distinguishes justified beliefs from superstition and lucky guesses.[79] However, justification does not guarantee truth. For example, if a person has strong but misleading evidence, they may form a justified belief that is false.[80]

Epistemologists often identify justification as one component of knowledge.[81] Usually, they are not only interested in whether a person has a sufficient reason to hold a belief, known as propositional justification, but also in whether the person holds the belief because or based on[note 6] this reason, known as doxastic justification. For example, if a person has sufficient reason to believe that a neighborhood is dangerous but forms this belief based on superstition then they have propositional justification but lack doxastic justification.[83]

Sources

[edit]Sources of justification are ways or cognitive capacities through which people acquire justification. Often-discussed sources include perception, introspection, memory, reason, and testimony, but there is no universal agreement to what extent they all provide valid justification.[84] Perception relies on sensory organs to gain empirical information. There are various forms of perception corresponding to different physical stimuli, such as visual, auditory, haptic, olfactory, and gustatory perception.[85] Perception is not merely the reception of sense impressions but an active process that selects, organizes, and interprets sensory signals.[86] Introspection is a closely related process focused not on external physical objects but on internal mental states. For example, seeing a bus at a bus station belongs to perception while feeling tired belongs to introspection.[87]

Rationalists understand reason as a source of justification for non-empirical facts. It is often used to explain how people can know about mathematical, logical, and conceptual truths. Reason is also responsible for inferential knowledge, in which one or several beliefs are used as premises to support another belief.[88] Memory depends on information provided by other sources, which it retains and recalls, like remembering a phone number perceived earlier.[89] Justification by testimony relies on information one person communicates to another person. This can happen by talking to each other but can also occur in other forms, like a letter, a newspaper, and a blog.[90]

Schools of thought

[edit]Skepticism, fallibilism, and relativism

[edit]Philosophical skepticism questions the human ability to arrive at knowledge. Some skeptics limit their criticism to certain domains of knowledge. For example, religious skeptics say that it is impossible to have certain knowledge about the existence of deities or other religious doctrines. Similarly, moral skeptics challenge the existence of moral knowledge and metaphysical skeptics say that humans cannot know ultimate reality.[91]

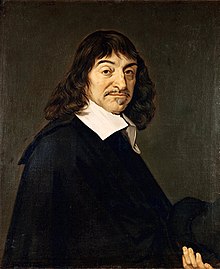

Global skepticism is the widest form of skepticism, asserting that there is no knowledge in any domain.[92] In ancient philosophy, this view was accepted by academic skeptics while Pyrrhonian skeptics recommended the suspension of belief to achieve a state of tranquility.[93] Overall, not many epistemologists have explicitly defended global skepticism. The influence of this position derives mainly from attempts by other philosophers to show that their theory overcomes the challenge of skepticism. For example, René Descartes used methodological doubt to find facts that cannot be doubted.[94]

One consideration in favor of global skepticism is the dream argument. It starts from the observation that, while people are dreaming, they are usually unaware of this. This inability to distinguish between dream and regular experience is used to argue that there is no certain knowledge since a person can never be sure that they are not dreaming.[95][note 7] Some critics assert that global skepticism is a self-refuting idea because denying the existence of knowledge is itself a knowledge claim. Another objection says that the abstract reasoning leading to skepticism is not convincing enough to overrule common sense.[97]

Fallibilism is another response to skepticism.[98] Fallibilists agree with skeptics that absolute certainty is impossible. Most fallibilists disagree with skeptics about the existence of knowledge, saying that there is knowledge since it does not require absolute certainty.[99] They emphasize the need to keep an open and inquisitive mind since doubt can never be fully excluded, even for well-established knowledge claims like thoroughly tested scientific theories.[100]

Epistemic relativism is a related view. It does not question the existence of knowledge in general but rejects the idea that there are universal epistemic standards or absolute principles that apply equally to everyone. This means that what a person knows depends on the subjective criteria or social conventions used to assess epistemic status.[101]

Empiricism and rationalism

[edit]

The debate between empiricism and rationalism centers on the origins of human knowledge. Empiricism emphasizes that sense experience is the primary source of all knowledge. Some empiricists express this view by stating that the mind is a blank slate that only develops ideas about the external world through the sense data it receives from the sensory organs. According to them, the mind can arrive at various additional insights by comparing impressions, combining them, generalizing to arrive at more abstract ideas, and deducing new conclusions from them. Empiricists say that all these mental operations depend on material from the senses and do not function on their own.[102]

Even though rationalists usually accept sense experience as one source of knowledge,[note 8] they also say that important forms of knowledge come directly from reason without sense experience,[104] like knowledge of mathematical and logical truths.[105] According to some rationalists, the mind possesses inborn ideas which it can access without the help of the senses. Others hold that there is an additional cognitive faculty, sometimes called rational intuition, through which people acquire nonempirical knowledge.[106] Some rationalists limit their discussion to the origin of concepts, saying that the mind relies on inborn categories to understand the world and organize experience.[107]

Foundationalism and coherentism

[edit]Foundationalists and coherentists disagree about the structure of knowledge.[108][note 9] Foundationalism distinguishes between basic and non-basic beliefs. A belief is basic if it is justified directly, meaning that its validity does not depend on the support of other beliefs. A belief is non-basic if it is justified by another belief.[110] For example, the belief that it rained last night is a non-basic belief if it is inferred from the observation that the street is wet.[111] According to foundationalism, basic beliefs are the foundation on which all other knowledge is built while non-basic beliefs constitute the superstructure resting on this foundation.[112]

Coherentists reject the distinction between basic and non-basic beliefs, saying that the justification of any belief depends on other beliefs. They assert that a belief must be in tune with other beliefs to amount to knowledge. This is the case if the beliefs are consistent and support each other. According to coherentism, justification is a holistic aspect determined by the whole system of beliefs, which resembles an interconnected web.[113]

The view of foundherentism is an intermediary position combining elements of both foundationalism and coherentism. It accepts the distinction between basic and non-basic beliefs while asserting that the justification of non-basic beliefs depends on coherence with other beliefs.[114]

Infinitism presents another approach to the structure of knowledge. It agrees with coherentism that there are no basic beliefs while rejecting the view that beliefs can support each other in a circular manner. Instead, it argues that beliefs form infinite justification chains, in which each link of the chain supports the belief following it and is supported by the belief preceding it.[115]

Internalism and externalism

[edit]The disagreement between internalism and externalism is about the sources of justification.[116][note 10] Internalists say that justification depends only on factors within the individual. Examples of such factors include perceptual experience, memories, and the possession of other beliefs. This view emphasizes the importance of the cognitive perspective of the individual in the form of their mental states. It is commonly associated with the idea that the relevant factors are accessible, meaning that the individual can become aware of their reasons for holding a justified belief through introspection and reflection.[118]

Externalism rejects this view, saying that at least some relevant factors are external to the individual. This means that the cognitive perspective of the individual is less central while other factors, specifically the relation to truth, become more important.[119] For instance, when considering the belief that a cup of coffee stands on the table, externalists are not only interested in the perceptual experience that led to this belief but also consider the quality of the person's eyesight, their ability to differentiate coffee from other beverages, and the circumstances under which they observed the cup.[120]

Evidentialism is an influential internalist view. It says that justification depends on the possession of evidence.[121] In this context, evidence for a belief is any information in the individual's mind that supports the belief. For example, the perceptual experience of rain is evidence for the belief that it is raining. Evidentialists have suggested various other forms of evidence, including memories, intuitions, and other beliefs.[122] According to evidentialism, a belief is justified if the individual's evidence supports the belief and they hold the belief on the basis of this evidence.[123]

Reliabilism is an externalist theory asserting that a reliable connection between belief and truth is required for justification.[124] Some reliabilists explain this in terms of reliable processes. According to this view, a belief is justified if it is produced by a reliable belief-formation process, like perception. A belief-formation process is reliable if most of the beliefs it causes are true. A slightly different view focuses on beliefs rather than belief-formation processes, saying that a belief is justified if it is a reliable indicator of the fact it presents. This means that the belief tracks the fact: the person believes it because it is a fact but would not believe it otherwise.[125]

Virtue epistemology is another type of externalism and is sometimes understood as a form of reliabilism. It says that a belief is justified if it manifests intellectual virtues. Intellectual virtues are capacities or traits that perform cognitive functions and help people form true beliefs. Suggested examples include faculties like vision, memory, and introspection.[126]

Others

[edit]In the epistemology of perception, direct and indirect realists disagree about the connection between the perceiver and the perceived object. Direct realists say that this connection is direct, meaning that there is no difference between the object present in perceptual experience and the physical object causing this experience. According to indirect realism, the connection is indirect since there are mental entities, like ideas or sense data, that mediate between the perceiver and the external world. The contrast between direct and indirect realism is important for explaining the nature of illusions.[127]

Constructivism in epistemology is the theory that how people view the world is not a simple reflection of external reality but an invention or a social construction. This view emphasizes the creative role of interpretation while undermining objectivity since social constructions may differ from society to society.[128]

According to contrastivism, knowledge is a comparative term, meaning that to know something involves distinguishing it from relevant alternatives. For example, if a person spots a bird in the garden, they may know that it is a sparrow rather than an eagle but they may not know that it is a sparrow rather than an indistinguishable sparrow hologram.[129]

Epistemic conservatism is a view about belief revision. It gives preference to the beliefs a person already has, asserting that a person should only change their beliefs if they have a good reason to. One motivation for adopting epistemic conservatism is that the cognitive resources of humans are limited, meaning that it is not feasible to constantly reexamine every belief.[130]

Pragmatist epistemology is a form of fallibilism that emphasizes the close relation between knowing and acting. It sees the pursuit of knowledge as an ongoing process guided by common sense and experience while always open to revision.[131]

Bayesian epistemology is a formal approach based on the idea that people have degrees of belief representing how certain they are. It uses probability theory to define norms of rationality that govern how certain people should be about their beliefs.[132]

Phenomenological epistemology emphasizes the importance of first-person experience. It distinguishes between the natural attitude focusing on objects, which is found in common sense and the natural sciences, and the phenomenological attitude focusing on the experience of objects, which aims to provide a presuppositionless description of how objects appear to the observer.[133]

Postmodern epistemology criticizes the conditions of knowledge in advanced societies. This concerns in particular the metanarrative of a constant progress of scientific knowledge leading to a universal and foundational understanding of reality.[134] Feminist epistemology critiques the effect of gender on knowledge. Among other topics, it explores how preconceptions about gender influence who has access to knowledge, how knowledge is produced, and which types of knowledge are valued in society.[135] Decolonial scholarship criticizes the global influence of Western knowledge systems, often with the aim of decolonizing knowledge to undermine Western hegemony.[136]

Various schools of epistemology are found in traditional Indian philosophy. Many of them focus on the different sources of knowledge, called pramāṇa. Perception, inference, and testimony are sources discussed by most schools. Other sources only considered by some schools are non-perception, which leads to knowledge of absences, and presumption.[137] Buddhist epistemology tends to focus on immediate experience, understood as the presentation of unique particulars without the involvement of secondary cognitive processes, like thought and desire.[138] Nyāya epistemology discusses the causal relation between the knower and the object of knowledge, which happens through reliable knowledge-formation processes. It sees perception as the primary source of knowledge, drawing a close connection between it and successful action.[139] Mīmāṃsā epistemology understands the holy scriptures known as the Vedas as a key source of knowledge while discussing the problem of their right interpretation.[140] Jain epistemology states that reality is many-sided, meaning that no single viewpoint can capture the entirety of truth.[141]

Branches

[edit]Some branches of epistemology focus on the problems of knowledge within specific academic disciplines. The epistemology of science examines how scientific knowledge is generated and what problems arise in the process of validating, justifying, and interpreting scientific claims. A key issue concerns the problem of how individual observations can support universal scientific laws. Further topics include the nature of scientific evidence and the aims of science.[142] The epistemology of mathematics studies the origin of mathematical knowledge. In exploring how mathematical theories are justified, it investigates the role of proofs and whether there are empirical sources of mathematical knowledge.[143]

Epistemological problems are found in most areas of philosophy. The epistemology of logic examines how people know that an argument is valid. For example, it explores how logicians justify that modus ponens is a correct rule of inference or that all contradictions are false.[144] Epistemologists of metaphysics investigate whether knowledge of ultimate reality is possible and what sources this knowledge could have.[145] Knowledge of moral statements, like the claim that lying is wrong, belongs to the epistemology of ethics. It studies the role of ethical intuitions, coherence among moral beliefs, and the problem of moral disagreement.[146] The ethics of belief is a closely related field covering the interrelation between epistemology and ethics. It examines the norms governing belief formation and asks whether violating them is morally wrong.[147]

Religious epistemology studies the role of knowledge and justification for religious doctrines and practices. It evaluates the weight and reliability of evidence from religious experience and holy scriptures while also asking whether the norms of reason should be applied to religious faith.[148] Social epistemology focuses on the social dimension of knowledge. While traditional epistemology is mainly interested in knowledge possessed by individuals, social epistemology covers knowledge acquisition, transmission, and evaluation within groups, with specific emphasis on how people rely on each other when seeking knowledge.[149] Historical epistemology examines how the understanding of knowledge and related concepts has changed over time. This concerns questions like whether the main issues in epistemology are perennial and to what extent past epistemological theories are relevant to contemporary debates. It is particularly concerned with scientific knowledge and practices associated with it.[150] It contrasts with the history of epistemology, which presents, reconstructs, and evaluates epistemological theories of philosophers in the past.[151][note 11]

Naturalized epistemology is closely associated with the natural sciences, relying on their methods and theories to examine knowledge. Naturalistic epistemologists focus on empirical observation to formulate their theories and are often critical of approaches to epistemology that proceed by a priori reasoning.[153] Evolutionary epistemology is a naturalistic approach that understands cognition as a product of evolution, examining knowledge and the cognitive faculties responsible for it from the perspective of natural selection.[154] Epistemologists of language explore the nature of linguistic knowledge, for example, how native speakers usually have the tacit knowledge to follow the rules of grammar even though they may be unable to explicitly articulate those rules.[155] Epistemologists of modality examine knowledge about what is possible and necessary.[156] Epistemic problems that arise when two people have diverging opinions on a topic are covered by the epistemology of disagreement.[157] Epistemologists of ignorance are interested in epistemic faults and gaps in knowledge.[158]

There are distinct areas of epistemology dedicated to specific sources of knowledge. Examples are the epistemology of perception,[159] the epistemology of memory,[160] and the epistemology of testimony.[161]

Some branches of epistemology are characterized by their research method. Formal epistemology employs formal tools found in logic and mathematics to investigate the nature of knowledge.[162][note 12] Experimental epistemologists rely in their research on empirical evidence about common knowledge practices.[164] Applied epistemology focuses on the practical application of epistemological principles to diverse real-world problems, like the reliability of knowledge claims on the internet, how to assess sexual assault allegations, and how racism may lead to epistemic injustice.[165][note 13]

Metaepistemologists examine the nature, goals, and research methods of epistemology. As a metatheory, it does not directly defend a position about which epistemological theories are correct but examines their fundamental concepts and background assumptions.[167][note 14]

Related fields

[edit]Epistemology and psychology were not defined as distinct fields until the 19th century; earlier investigations about knowledge often do not fit neatly into today's academic categories.[169] Both contemporary disciplines study beliefs and the mental processes responsible for their formation and change. One important contrast is that psychology describes what beliefs people have and how they acquire them, thereby explaining why someone has a specific belief. The focus of epistemology is on evaluating beliefs, leading to a judgment about whether a belief is justified and rational in a particular case.[170] Epistemology has a similar intimate connection to cognitive science, which understands mental events as processes that transform information.[171] Artificial intelligence relies on the insights of epistemology and cognitive science to implement concrete solutions to problems associated with knowledge representation and automatic reasoning.[172]

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. For epistemology, it is relevant to inferential knowledge, which arises when a person reasons from one known fact to another.[173] This is the case, for example, if a person does not know directly that but comes to infer it based on their knowledge that , , and .[174] Whether an inferential belief amounts to knowledge depends on the form of reasoning used, in particular, that the process does not violate the laws of logic.[175] Another overlap between the two fields is found in the epistemic approach to fallacy theory.[176] Fallacies are faulty arguments based on incorrect reasoning.[177] The epistemic approach to fallacies explains why they are faulty, stating that arguments aim to expand knowledge. According to this view, an argument is a fallacy if it fails to do so.[178]

Both decision theory and epistemology are interested in the foundations of rational thought and the role of beliefs. Unlike many approaches in epistemology, the main focus of decision theory lies less in the theoretical and more in the practical side, exploring how beliefs are translated into action.[179] Decision theorists examine the reasoning involved in decision-making and the standards of good decisions.[180] They identify beliefs as a central aspect of decision-making. One of their innovations is to distinguish between weaker and stronger beliefs. This helps them take the effect of uncertainty on decisions into consideration.[181]

Epistemology and education have a shared interest in knowledge, with one difference being that education focuses on the transmission of knowledge, exploring the roles of both learner and teacher.[182] Learning theory examines how people acquire knowledge.[183] Behavioral learning theories explain the process in terms of behavior changes, for example, by associating a certain response with a particular stimulus.[184] Cognitive learning theories study how the cognitive processes that affect knowledge acquisition transform information.[185] Pedagogy looks at the transmission of knowledge from the teacher's side, exploring the teaching methods they may employ.[186] In teacher-centered methods, the teacher takes the role of the main authority delivering knowledge and guiding the learning process. In student-centered methods, the teacher mainly supports and facilitates the learning process while the students take a more active role.[187] The beliefs students have about knowledge, called personal epistemology, affect their intellectual development and learning success.[188]

The anthropology of knowledge examines how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated. It studies the social and cultural circumstances that affect how knowledge is reproduced and changes, covering the role of institutions like university departments and scientific journals as well as face-to-face discussions and online communications. It understands knowledge in a wide sense that encompasses various forms of understanding and culture, including practical skills. Unlike epistemology, it is not interested in whether a belief is true or justified but in how understanding is reproduced in society.[189] The sociology of knowledge is a closely related field with a similar conception of knowledge. It explores how physical, demographic, economic, and sociocultural factors impact knowledge. It examines in what sociohistorical contexts knowledge emerges and the effects it has on people, for example, how socioeconomic conditions are related to the dominant ideology in a society.[190]

History

[edit]Early reflections on the nature and sources of knowledge are found in ancient history. In ancient Greek philosophy, Plato (427–347 BCE) studied what knowledge is, examining how it differs from true opinion by being based on good reasons.[191] According to him, the process of learning something is a form of recollection in which the soul remembers what it already knew before.[192][note 15] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was particularly interested in scientific knowledge, exploring the role of sensory experience and how to make inferences from general principles.[194] The Hellenistic schools began to arise in the 4th century BCE. The Epicureans defended the position that sensations are always accurate and act as the supreme standard of judgments.[195] Similarly, the Stoics said that only clear and distinct sensory impressions are true.[196] The skepticists questioned that knowledge is possible, recommending instead suspension of judgment to arrive at a state of tranquility.[197]

The Upanishads, philosophical scriptures composed in ancient India between 700 and 300 BCE, examined how people acquire knowledge, including the role of introspection, comparison, and deduction.[198] In the 6th century BCE, the school of Ajñana developed a radical skepticism questioning the possibility and usefulness of knowledge.[199] The school of Nyaya emerged in the 2nd century BCE and provided a systematic treatment of how people acquire knowledge, distinguishing between valid and invalid sources.[200] When Buddhist philosophers later became interested in epistemology, they relied on concepts developed in Nyaya and other traditions.[201] Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti (6th or 7th century CE)[202] analyzed the process of knowing as a series of causally related events.[203]

The relation between reason and faith was a central topic in the medieval period.[204] In Arabic–Persian philosophy, al-Farabi (c. 870–950) and Averroes (1126–1198) discussed how philosophy and theology interact and which is the better vehicle to truth.[205] Al-Ghazali (c. 1056–1111) criticized many of the core teachings of previous Islamic philosophers, saying that they rely on unproven assumptions.[206] In Western philosophy, Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) proposed that theological teaching and philosophical inquiry are in harmony and complement each other.[207] Peter Abelard (1079–1142) argued against unquestioned theological authorities and said that all things are open to rational doubt.[208] Influenced by Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) stated that "nothing is in the intellect unless it first appeared in the senses".[209] According to William of Ockham (c. 1285–1349), the mind perceives the world directly.[210]

The course of modern philosophy was shaped by René Descartes (1596–1650), who claimed that philosophy must begin from a position of indubitable knowledge of first principles. Inspired by skepticism, he aimed to find absolutely certain knowledge by encountering truths that cannot be doubted. He thought that this is the case for the assertion "I think, therefore I am", from which he construct the rest of his philosophical system.[211] Descartes, together with Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), belonged to the school of rationalism, which asserts that the mind possesses innate ideas independent of experience.[212] John Locke (1632–1704) rejected this view in favor of an empiricism according to which the mind is a blank slate. This means that all ideas depend on sense experience, either as "ideas of sense", which are directly presented through the senses, or as "ideas of reflection", which the mind creates by reflecting on ideas of sense.[213] David Hume (1711–1776) used this idea to explore the limits of what people can know. He said that knowledge of facts is never certain, adding that knowledge of relations between ideas, like mathematical truths, can be certain but contains no information about the world.[214] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to find a middle position between rationalism and empiricism by identifying a type of knowledge that Hume had missed. For Kant, this is knowledge about principles that underlie all experience and structure it, such as spatial and temporal relations and fundamental categories of understanding.[215]

In the 19th-century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) argued against empiricism, saying that sensory impressions on their own cannot amount to knowledge since all knowledge is actively structured by the knowing subject.[216] John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) defended a wide-sweeping form of empiricism and explained knowledge of general truths through inductive reasoning.[217] Charles Peirce (1839–1914) thought that all knowledge is fallible, emphasizing that knowledge seekers should always be ready to revise their beliefs if new evidence is encountered. He used this idea to argue against Cartesian foundationalism seeking absolutely certain truths.[218]

In the 20th century, fallibilism was further explored by J. L. Austin (1911–1960) and Karl Popper (1902–1994).[219] In continental philosophy, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) applied the skeptic idea of suspending judgment to the study of experience. By not judging whether an experience is accurate or not, he tried to describe the internal structure of experience instead.[220] Logical positivists, like A. J. Ayer (1910–1989), said that all knowledge is either empirical or analytic.[221] Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) developed an empiricist sense-datum theory, distinguishing between direct knowledge by acquaintance of sense data and indirect knowledge by description, which is inferred from knowledge by acquaintance.[222] Common sense had a central place in G. E. Moore's (1873–1958) epistemology. He used trivial observations, like the fact that he has two hands, to argue against abstract philosophical theories that deviate from common sense.[223] Ordinary language philosophy, as practiced by the late Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), is a similar approach that tries to extract epistemological insights from how ordinary language is used.[224]

Edmund Gettier (1927–2021) conceived counterexamples against the idea that knowledge is the same as justified true belief. These counterexamples prompted many philosophers to suggest alternative definitions of knowledge.[225] One of the alternatives considered was reliabilism, which says that knowledge requires reliable sources, shifting the focus away from justification.[226] Virtue epistemology, a closely related response, analyses belief formation in terms of the intellectual virtues or cognitive competencies involved in the process.[227] Naturalized epistemology, as conceived by Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000), employs concepts and ideas from the natural sciences to formulate its theories.[228] Other developments in late 20th-century epistemology were the emergence of social, feminist, and historical epistemology.[229]

See also

[edit]- Epistemological pluralism – term used in philosophy, economics, and virtually any field of study to refer to different ways of knowing things, different epistemological methodologies for attaining a fuller description of a particular field

- Evolutionary epistemology – Ambiguous term applied to several concepts

- Knowledge falsification – Deliberate misrepresentation of knowledge

- Knowledge-first epistemology – 2000 philosophical essay by Timothy Williamson

- Moral epistemology – Branch of ethics seeking to understand ethical properties

- Noölogy – Spanish philosopher (1898–1983)

- Personal epistemology – Cognition about knowledge and knowing

- Reformed epistemology – School of philosophical thought

- Self-evidence – Epistemologically probative proposition

- Sociology of knowledge – Field of study

- Theory of Knowledge (IB Course) – Compulsory International Baccalaureate subject

- Axiology – Philosophical study of value

- Praxiology – Theory of human action

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Less commonly, the term "gnoseology" is also used as a synonym.[7]

- ^ Despite this contrast, epistemologists may rely on insights from the empirical sciences in formulating their normative theories.[13]

- ^ As a label for a branch of philosophy, the term "epistemology" was first employed in 1854 by James E. Ferrier.[16] In a different context, the word was used as early as 1847 in New York's Eclectic Magazine.[17] As the term had not been coined before the 19th century, earlier philosophers did not explicitly label their theories as epistemology and often explored it in combination with psychology.[18] According to philosopher Thomas Sturm, it is an open question how relevant the epistemological problems addressed by past philosophers are to contemporary philosophy.[19]

- ^ Other synonyms include declarative knowledge and descriptive knowledge.[33]

- ^ The accuracy of the label traditional analysis is debated since it suggests widespread acceptance within the history of philosophy, an idea not shared by all scholars.[47]

- ^ The relation between a belief and the reason on which it rests is called basing relation.[82]

- ^ The brain in a vat is a similar thought experiment assuming that a person does not have a body but is merely a brain receiving electrical stimuli indistinguishable from the stimuli a brain in a body would receive. This argument also leads to the conclusion of global skepticism based on the claim that it is not possible to distinguish stimuli representing the actual world from simulated stimuli.[96]

- ^ Some forms of extreme rationalism, found in ancient Greek philosophy, see reason as the sole source of knowledge.[103]

- ^ Both can be understood as responses to the regress problem.[109]

- ^ The internalist-externalist debate in epistemology is different from the internalism-externalism debate in philosophy of mind, which asks whether mental states depend only on the individual or also on their environment.[117]

- ^ The precise characterization of the contrast is disputed.[152]

- ^ It is closely related to computational epistemology, which examines the interrelation between knowledge and computational processes.[163]

- ^ Epistemic injustice happens when valid knowledge claims are dismissed or misrepresented.[166]

- ^ Nonetheless, metaepistemological insights can have various indirect effects on disputes in epistemology.[168]

- ^ To argue for this point, Plato uses the example of a slave boy, who manages to answer a series of geometry questions even though they never studied geometry.[193]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Steup, Matthias (2005). "Epistemology". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 ed.). Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Truncellito.

- ^ Borchert, Donald M., ed. (1967). "Epistemology". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 3. Macmillan.

- ^ Stroll, Avrum. "epistemology". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Steup, Matthias; Neta, Ram (14 December 2005). "Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Wenning, Carl J. (Autumn 2009). "Scientific epistemology: How scientists know what they know" (PDF). Journal of Physics Teacher Education Online. 5 (2): 3–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2024

- ^

- Truncellito, Lead Section

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005, pp. 49–50

- Crumley II 2009, p. 16

- Carter & Littlejohn 2021, Introduction: 1. What Is Epistemology?

- Moser 2005, p. 3

- ^

- Fumerton 2006, pp. 1–2

- Moser 2005, p. 4

- ^

- Brenner 1993, p. 16

- Palmquist 2010, p. 800

- Jenicek 2018, p. 31

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, Lead Section

- Moss 2021, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 16

- Carter & Littlejohn 2021, Introduction: 1. What Is Epistemology?

- ^ O′Donohue & Kitchener 1996, p. 2

- ^

- Audi 2003, pp. 258–259

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 3–4

- Campbell 2024, Lead Section

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, Lead Section

- Scott 2002, p. 30

- Wolenski 2004, p. 3

- ^ Wolenski 2004, p. 3

- ^ Oxford University Press 2024

- ^ Alston 2005, pp. 1–2

- ^ Sturm 2011, pp. 308–309

- ^

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 109

- Steup & Neta 2020, Lead Section, § 1. The Varieties of Cognitive Success

- HarperCollins 2022a

- ^

- Klausen 2015, pp. 813–818

- Lackey 2021, pp. 111–112

- ^

- ^

- HarperCollins 2022b

- Walton 2005, pp. 59, 64

- ^

- Gross & McGoey 2015, p. 1–4

- Haas & Vogt 2015, pp. 17–18

- Blaauw & Pritchard 2005, p. 79

- ^

- Markie & Folescu 2023, § 1. Introduction

- Rescher 2009, pp. 2, 6

- Stoltz 2021, p. 120

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. 10, 93

- Rescher 2009a, pp. x–xi, 57–58

- Dika 2023, p. 163

- ^

- Rescher 2009, pp. 2, 6

- Rescher 2009a, pp. 140–141

- ^

- Wilson 2008, p. 314

- Pritchard 2005, pp. 18

- Hetherington, "Fallibilism", Lead section, § 8. Implications of Fallibilism: No Knowledge?

- ^ Brown 2016, p. 104

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Barnett 1990, p. 40

- Lilley, Lightfoot & Amaral 2004, pp. 162–163

- ^

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ^ Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1b. Knowledge-That

- ^ Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1b. Knowledge-That

- ^

- Morrison 2005, p. 371

- Reif 2008, p. 33

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 93

- ^ Pritchard 2013, p. 4

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Stanley & Willlamson 2001, pp. 411–412

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1d. Knowing-How

- Pritchard 2013, p. 3

- ^

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- Stroll 2023, § St. Anselm of Canterbury

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ^

- Stroll 2023, § A Priori and a Posteriori Knowledge

- Baehr, "A Priori and A Posteriori", Lead section

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- ^

- Baehr, "A Priori and A Posteriori", Lead Section

- Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ^

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- Baehr, "A Priori and A Posteriori", Lead section, § 1. An Initial Characterization

- Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ^

- ^ Juhl & Loomis 2009, p. 4

- ^

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 54–55

- Ayers 2019, p. 4

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead section

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 53–54

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 61–62

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem

- ^

- Rodríguez 2018, pp. 29–32

- Goldman 1976, pp. 771–773

- Sudduth, § 2b. Defeasibility Analyses and Propositional Defeaters

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 10.2 Fake Barn Cases

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 61–62

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 8. Epistemic Luck

- ^

- Pritchard 2005, pp. 1–4

- Broncano-Berrocal & Carter 2017, Lead section

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 65

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead section, § 3. The Gettier Problem

- ^ Crumley II 2009, pp. 67–68

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 6.1 Reliabilist Theories of Knowledge

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 5.1 Sensitivity

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 75

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 4. No False Lemmas

- ^ Crumley II 2009, p. 69

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 5c. Questioning the Gettier Problem, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Kraft 2012, pp. 49–50

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 93–94, 104–105

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.3 Knowing Facts

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- ^

- Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 10–11

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- ^

- Pritchard 2013, p. 11

- McCormick 2014, p. 42

- ^ Pritchard 2013, pp. 11–12

- ^

- Stehr & Adolf 2016, pp. 483–485

- Powell 2020, pp. 132–133

- Meirmans et al. 2019, pp. 754–756

- Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- ^

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 1. Value problems

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- Greco 2021, § The Value of Knowledge

- ^

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 1. Value problems

- Plato 2002, pp. 89–90, 97b–98a

- ^

- Olsson 2011, p. 875

- Greco 2021, § The Value of Knowledge

- ^ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 6. Other Accounts of the Value of Knowledge

- ^

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 15–16

- Greco 2021, § The Value of Knowledge

- ^ a b c d e "Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Formal Representations of Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Truth". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Plato (5 October 2008). Gorgias. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2017 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^

- Goldman & Bender 2005, p. 465

- Kvanvig 2011, pp. 25–26

- ^

- Goldman & Bender 2005, p. 465

- Kvanvig 2011, pp. 25–26

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 83–84

- Olsson 2016

- ^

- Kvanvig 2011, p. 25

- Foley 1998, Lead section

- ^ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 149

- Comesaña & Comesaña 2022, p. 44

- ^ Blaauw & Pritchard 2005, pp. 92–93

- ^ Silva & Oliveira 2022, pp. 1–4

- ^

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3.2 Kinds of Justification

- Silva & Oliveira 2022, pp. 1–4

- ^

- Kern 2017, pp. 8–10, 133

- Smith 2023, p. 3

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 5. Sources of Knowledge and Justification

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 3. Ways of Knowing

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 5.1 Perception

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 3. Ways of Knowing

- ^

- Khatoon 2012, p. 104

- Martin 1998, Lead Section

- ^ Steup & Neta 2024, § 5.2 Introspection

- ^

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 3d. Knowing by Thinking-Plus-Observing

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 5.4 Reason

- Audi 2002, pp. 85, 90–91

- Audi 2006, p. 38

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 5.3 Memory

- Audi 2002, pp. 72–75

- Gardiner 2001, pp. 1351–1352

- Michaelian & Sutton 2017

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 5.5 Testimony

- Leonard 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Reductionism and Non-Reductionism

- Green 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Cohen 1998, § Article Summary

- Hookway 2005, p. 838

- Moser 2011, p. 200

- ^

- Hookway 2005, p. 838

- Bergmann 2021, p. 57

- ^

- Hazlett 2014, p. 18

- Levine 1999, p. 11

- ^

- Hookway 2005, p. 838

- Comesaña & Klein 2024, Lead Section

- ^

- Windt 2021, § 1.1 Cartesian Dream Skepticism

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Hetherington, "Knowledge", § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- ^

- Hookway 2005, p. 838

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ^

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 6.2 Responses to the Closure Argument

- Reed 2015, p. 75

- ^ Cohen 1998, § 1. The philosophical problem of scepticism, § 2. Responses to scepticism

- ^

- Hetherington, "Fallibilism", Lead section, § 9. Implications of Fallibilism: Knowing Fallibly?

- Rescher 1998, § Article Summary

- ^

- Rescher 1998, § Article Summary

- Hetherington, "Fallibilism", § 9. Implications of Fallibilism: Knowing Fallibly?

- ^

- Carter 2017, p. 292

- Luper 2004, pp. 271–272

- ^

- Lacey 2005, p. 242

- Markie & Folescu 2023, Lead section, § 1.2 Empiricism

- ^ Lacey 2005a, p. 783

- ^

- Lacey 2005a, p. 783

- Markie & Folescu 2023, Lead section, § 1. Introduction

- ^ Tieszen 2005, p. 175

- ^

- Lacey 2005a, p. 783

- Markie & Folescu 2023, Lead section, § 1. Introduction

- Hales 2009, p. 29

- ^

- Lacey 2005a, p. 783

- Markie & Folescu 2023, Lead section, § 1. Introduction

- ^

- Audi 1988, pp. 407–408

- Stairs 2017, pp. 155–156

- Margolis 2007, p. 214

- ^ Bradley 2015, p. 170

- ^

- Stairs 2017, pp. 155–156

- Margolis 2007, p. 214

- ^ Stairs 2017, p. 155

- ^

- Stairs 2017, pp. 155–156

- Margolis 2007, p. 214

- ^

- Stairs 2017, pp. 156–157

- O'Brien 2006, p. 77

- ^

- Ruppert, Schlüter & Seide 2016, p. 59

- Tramel 2008, pp. 215–216

- ^

- Bradley 2015, pp. 170–171

- Stairs 2017, pp. 155–156

- ^

- Pappas 2023, Lead section

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 159–160

- Fumerton 2011, Lead section

- ^

- Bernecker 2013, Note 1

- Wilson 2023

- ^

- Pappas 2023, Lead section

- Poston, Lead section

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 159–160

- ^

- Pappas 2023, Lead section

- Poston, Lead section

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 159–160

- ^ Crumley II 2009, p. 160

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 99, 298

- Carter & Littlejohn 2021, § 9.3.3 An Evidentialist Argument

- Mittag, Lead section

- ^ Mittag, § 2b. Evidence

- ^ Crumley II 2009, pp. 99, 298

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 83, 301

- Olsson 2016

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, p. 84

- Lyons 2016, pp. 160–162

- Olsson 2016

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 175–176

- Baehr, "Virtue Epistemology", Lead section, § 1. Introduction to Virtue Epistemology

- ^

- Brown 1992, p. 341

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 268–269, 277–278, 300–301

- ^

- Chiari & Nuzzo 2009, p. 21

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 215–216, 301

- ^

- Cockram & Morton 2017

- Baumann 2016, pp. 59–60

- ^

- Foley 1983, p. 165

- Vahid, Lead section, § 1. Doxastic Conservatism: The Debate

- ^

- Legg & Hookway 2021, Lead section, § 4. Pragmatist Epistemology

- Kelly & Cordeiro 2020, p. 1

- ^

- ^

- Pietersma 2000, pp. 3–4

- Howarth 1998, § Article Summary

- ^

- Sharpe 2018, pp. 318–319

- Best & Kellner 1991, p. 165

- ^

- Anderson 1995, p. 50

- Anderson 2024, Lead section

- ^

- Lee 2017, p. 67

- Dreyer 2017, pp. 1–7

- ^

- Phillips 1998, Lead section

- Phillips & Vaidya 2024, Lead section

- Bhatt & Mehrotra 2017, pp. 12–13

- ^

- Phillips 1998, § 1. Buddhist Pragmatism and Coherentism

- Siderits 2021, p. 332

- ^ Phillips 1998, § 2. Nyāya Reliabilism

- ^ Phillips 1998, § 2. Mīmāṃsā self-certificationalism

- ^

- Webb, § 2. Epistemology and Logic

- Sethia 2004, p. 93

- ^

- McCain & Kampourakis 2019, pp. xiii–xiv

- Bird 2010, p. 5

- Merritt 2020, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Murawski 2004, pp. 571–572

- Sierpinska & Lerman 1996, pp. 827–828

- ^ Warren 2020, § 6. The Epistemology of Logic

- ^

- McDaniel 2020, § 7.2 The Epistemology of Metaphysics

- Van Inwagen, Sullivan & Bernstein 2023, § 5. Is Metaphysics Possible?

- ^

- DeLapp, Lead section, § 6. Epistemological Issues in Metaethics

- Sayre-McCord 2023, § 5. Moral Epistemology

- ^ Chignell 2018, Lead section

- ^

- McNabb 2019, p. 1–3, 22–23

- Howard-Snyder & McKaughan 2023, pp. 96–97

- ^

- Tanesini 2017, Lead section

- O’Connor, Goldberg & Goldman 2024, Lead section, § 1. What is Social Epistemology?

- ^

- Ávila & Almeida 2023, p. 235

- Vermeir 2013, pp. 65–66

- Sturm 2011, pp. 303–304, 306, 308

- ^ Sturm 2011, pp. 303–304, 08–309

- ^ Sturm 2011, p. 304

- ^

- Crumley II 2009, pp. 183–184, 188–189, 300

- Wrenn, Lead section

- Rysiew 2021, § 2. 'Epistemology Naturalized'

- ^

- Bradie & Harms 2023, Lead section

- Gontier, Lead section

- ^ Barber 2003, pp. 1–3, 10–11, 15

- ^ Vaidya & Wallner 2021, pp. 1909–1910

- ^ Croce 2023, Lead section

- ^ Maguire 2015, pp. 33–34

- ^ Siegel, Silins & Matthen 2014, p. 781

- ^ Conee 1998, Lead section

- ^ Pritchard 2004, p. 326

- ^ Douven & Schupbach 2014, Lead section

- ^

- Segura 2009, pp. 557–558

- Hendricks 2006, p. 115

- ^ Beebe 2017, Lead section

- ^ Lackey 2021, pp. 3, 8–9, 13

- ^

- Fricker 2007, pp. 1–2

- Crichton, Carel & Kidd 2017, pp. 65–66

- ^

- Gerken 2018, Lead section

- Mchugh, Way & Whiting 2019, pp. 1–2

- ^ Gerken 2018, Lead section

- ^ Alston 2006, p. 2

- ^

- Kitchener 1992, p. 119

- Crumley II 2009, p. 16

- Schmitt 2004, pp. 841–842

- ^

- Schmitt 2004, pp. 841–842

- Friedenberg, Silverman & Spivey 2022, pp. 2–3

- ^ Wheeler & Pereira 2004, pp. 469–470, 472, 491

- ^

- Rosenberg 2002, p. 184

- Steup & Neta 2024, § 4.1 Foundationalism

- Audi 2002, p. 90

- ^ Clark 2009, p. 516

- ^ Stairs 2017, p. 156

- ^ Hansen 2023, § 3.5 The epistemic approach to fallacies

- ^

- Hansen 2023, Lead Section

- Chatfield 2017, p. 194

- ^ Hansen 2023, § 3.5 The epistemic approach to fallacies

- ^

- Kaplan 2005, p. 434, 443–444

- Steele & Stefánsson 2020, Lead Section, § 7. Concluding remarks

- Hooker, Leach & McClennen 2012, pp. xiii–xiv

- ^ Steele & Stefánsson 2020, Lead Section

- ^

- Kaplan 2005, p. 434, 443–444

- Steele & Stefánsson 2020, § 7. Concluding remarks

- ^

- ^

- Kelly 2004, pp. 183–184

- Harasim 2017, p. 4

- ^ Harasim 2017, p. 11

- ^ Harasim 2017, pp. 11–12

- ^

- Watkins & Mortimore 1999, pp. 1–3

- Payne 2003, p. 264

- Gabriel 2022, p. 16

- Turuthi, Njagi & Chemwei 2017, p. 365

- ^ Emaliana 2017, pp. 59–61

- ^

- Hofer 2008, pp. 3–4

- Hofer 2001, pp. 353–354, 369–370

- ^

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72

- Barth 2002, pp. 1–2

- ^

- ^

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 260

- Pappas 1998, § Ancient philosophy

- ^ Pappas 1998, § Ancient philosophy

- ^ Pappas 1998, § Ancient philosophy

- ^

- Pappas 1998, § Ancient philosophy

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 260

- Wolenski 2004, p. 7

- ^

- Hamlyn 2006, pp. 287–288

- Wolenski 2004, p. 8

- ^

- Hamlyn 2006, p. 288

- Vogt 2011, p. 44

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, p. 8

- Pappas 1998, § Ancient philosophy

- ^ Black, Lead Section

- ^

- Fountoulakis 2021, p. 23

- Warder 1998, pp. 43–44

- Fletcher et al. 2020, p. 46

- ^

- Prasad 1987, p. 48

- Dasti, Lead Section

- Bhatt 1989, p. 72

- ^

- Prasad 1987, p. 6

- Dunne 2006, p. 753

- ^ Bonevac 2023, p. xviii

- ^ Dunne 2006, p. 753

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 10–11

- Koterski 2011, pp. 9–10

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, p. 11

- Schoenbaum 2015, p. 181

- ^

- Griffel 2020, Lead Section, § 3. Al-Ghazâlî's 'Refutations' of falsafa and Ismâ'îlism

- Vassilopoulou & Clark 2009, p. 303

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, p. 11

- Holopainen 2010, p. 75

- ^ Wolenski 2004, p. 11

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, p. 11

- Hamlyn 2006, pp. 289–290

- ^

- Kaye, Lead Section, § 4a. Direct Realist Empiricism

- Antognazza 2024, p. 86

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 14–15

- Hamlyn 2006, p. 291

- ^

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 261

- Evans 2018, p. 298

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 17–18

- Hamlyn 2006, pp. 298–299

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 261

- ^

- Coventry & Merrill 2018, p. 161

- Pappas 1998, § Modern philosophy: from Hume to Peirce

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 22–23

- ^

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 27–30

- Pappas 1998, § Modern philosophy: from Hume to Peirce

- ^

- Pappas 1998, § Modern philosophy: from Hume to Peirce

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 262

- ^

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 262

- Hamlyn 2006, p. 312

- ^ Pappas 1998, § Modern philosophy: from Hume to Peirce

- ^

- Pappas 1998, § Twentieth Century

- Kvasz & Zeleňák 2009, p. 71

- ^

- Rockmore 2011, pp. 131–132

- Wolenski 2004, p. 44

- Hamlyn 2006, p. 312

- ^ Hamlyn 2005, p. 262

- ^

- Pappas 1998, § Twentieth Century

- Hamlyn 2006, p. 315

- Wolenski 2004, pp. 48–49

- ^

- Baldwin 2010, § 6. Common Sense and Certainty

- Wolenski 2004, p. 49

- ^ Hamlyn 2006, pp. 317–318

- ^

- Hamlyn 2005, p. 262

- Beilby 2017, p. 74

- Pappas 1998, § Twentieth Century

- ^

- Goldman & Beddor 2021, Lead Section, § 1. A Paradigm Shift in Analytic Epistemology

- Pappas 1998, § Twentieth Century, § Recent Issues

- ^

- Goldman & Beddor 2021, § 4.1 Virtue Reliabilism

- Crumley II 2009, p. 175

- ^ Crumley II 2009, pp. 183–184, 188–189

- ^

- Pappas 1998, § Recent Issues

- Vagelli 2019, p. 96

References specific to notes

[edit]

- ^ Alston, William P. (1 January 2006). Beyond "Justification": Dimensions of Epistemic Evaluation. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501720574. ISBN 978-1-5017-2057-4.

- ^ Ayers, Michael; Antognazza, Maria Rosa (18 April 2019). "Knowledge and Belief from Plato to Locke". Knowing and Seeing. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–33. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198833567.003.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-883356-7. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Ballantyne, Nathan (31 October 2019). Knowing Our Limits (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190847289.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-084728-9.

- ^ Frede, Dorothea (18 December 2020). "Plato's Forms as Functions and Structures". History of Philosophy & Logical Analysis. 23 (2): 291–316. doi:10.30965/26664275-02302002. ISSN 2666-4283. S2CID 234562680.

- ^ Floridi, Luciano (1 July 1996). Scepticism and the Foundation of Epistemology: A Study in the Metalogical Fallacies. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004247246_002. ISBN 978-90-04-24724-6.

- ^ Fumerton, Richard (2003). "13: Introspection and Internalism". In Nuccetelli, Susana (ed.). New essays on semantic externalism and self-knowledge. MIT Press. pp. 257–276. ISBN 0262140837.

- ^ Kornblith, H. (1985). "Ever Since Descartes". The Monist. 68 (2). Oxford University Press: 264–276. doi:10.5840/monist198568227. ISSN 0026-9662. JSTOR 27902915. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Littlejohn, Clayton. "The New Evil Demon Problem". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosoph. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Popkin, Richard H. (1979). The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza (1 ed.). Berkeley Los Angeles London: University of California Press. doi:10.2307/jj.6142252. ISBN 9780520038769.

- ^ Robinson, Howard (2023). "Dualism". In Zalta, E. N.; Nodelman, U. (eds.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Parry, Richard (2021). "Episteme and Techne". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.).

Sources

[edit]- Allwood, Carl Martin (2013). "Anthropology of Knowledge". The Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 69–72. doi:10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp025. ISBN 978-1-118-33989-3. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Alston, William Payne (2005). Beyond Justification: Dimensions of Epistemic Evaluation. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4291-5.

- Anderson, Elizabeth (1995). "Feminist Epistemology: An Interpretation and a Defense". Hypatia. 10 (3): 50–84. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1995.tb00737.x. ISSN 0887-5367. JSTOR 3810237.

- Anderson, Elizabeth (2024). "Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- Antognazza, Maria Rosa (2024). "Knowledge as Presence and Presentation: Highlights from the History of Knowledge-First Epistemology". In Logins, Arturs; Vollet, Jacques-Henri (eds.). Putting Knowledge to Work. Oxford University PRess. ISBN 9780192882370.

- Audi, Robert (1988). "Foundationalism, Coherentism, and Epistemological Dogmatism". Philosophical Perspectives. 2: 407–442. doi:10.2307/2214083. JSTOR 2214083.

- Audi, Robert (2002). "The Sources of Knowledge". The Oxford Handbook of Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–94. ISBN 978-0-19-513005-8. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- Audi, Robert (2003). Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28108-3.

- Audi, Robert (2006). "Testimony, Credulity, and Veracity". In Lackey, Jennifer; Sosa, Ernest (eds.). The Epistemology of Testimony. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-153473-7.

- Ávila, Gabriel da Costa; Almeida, Tiago Santos (2023). "Lorraine Daston's Historical Epistemology: Style, Program, and School". In Condé, Mauro L.; Salomon, Marlon (eds.). Handbook for the Historiography of Science. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-031-27510-4.

- Ayers, Michael (2019). Knowing and Seeing: Groundwork for a new empiricism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-257012-3.

- Baehr, Jason S. "Virtue Epistemology". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- Baehr, Jason S. "A Priori and A Posteriori". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Baldwin, Tom (2010). "George Edward Moore". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- Barber, Alex (2003). "Introduction". In Barber, Alex (ed.). Epistemology of Language. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925057-8.

- Barnett, Ronald (1990). The Idea Of Higher Education. Open University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-335-09420-2. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- Barth, Fredrik (2002). "An Anthropology of Knowledge". Current Anthropology. 43 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1086/324131. hdl:1956/4191. ISSN 0011-3204.

- Baumann, Peter (2016). "Epistemic Contrastivism, Knowledge and Practical Reasoning". Erkenntnis. 81 (1): 59–68. doi:10.1007/s10670-015-9728-z.

- Beebe, James (2017). "Experimental epistemology". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-P067-1. ISBN 978-0-415-25069-6. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Beilby, James (2017). Epistemology as Theology: An Evaluation of Alvin Plantinga's Religious Epistemology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-93932-4.

- Bergmann, Michael (2021). Radical Skepticism and Epistemic Intuition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-265357-4.

- Bernecker, Sven (3 September 2013). "Triangular Externalism". In Lepore, Ernie; Ludwig, Kirk (eds.). A Companion to Donald Davidson (1 ed.). Wiley. pp. 443–455. doi:10.1002/9781118328408.ch25. ISBN 978-0-470-67370-6. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Best, Steven; Kellner, Douglas (1991). Postmodern Theory: Critical Interrogations. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-349-21718-2.

- Bhatt, Govardhan P. (1989). The Basic Ways of Knowing: An In-depth Study of Kumārila's Contribution to Indian Epistemology (Bhatt 1989 p72 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-0580-4.

- Bhatt, S. R.; Mehrotra, Anu (2017). Buddhist Epistemology. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-4114-7.

- Bird, Alexander (2010). "The epistemology of science—a bird's-eye view". Synthese. 175: 5–16. doi:10.1007/s11229-010-9740-4. ISSN 0039-7857. JSTOR 40801354.

- Blaauw, Martijn; Pritchard, Duncan (2005). Epistemology A - Z. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2213-6.

- Black, Brian. "Upanisads". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- Bonevac, Daniel (2023). Historical Dictionary of Ethics. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-7572-9.