Portrait of Isabella d'Este (Titian)

| Isabella in Black | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Titian |

| Year | 1530s |

| Type | Oil on Canvas |

| Subject | assumed as Isabella d'Este (uncertain identification) |

| Dimensions | 102 cm × 64 cm (40 in × 25 in) |

| Location | Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna |

| Accession | GG 83 |

Isabella in Black (also called Portrait of Isabella d'Este) is a portrait of a young woman by Titian. It can be dated to the 1530s and is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The artist and the date are undisputed. Beyond the museum documentation, there are repeated doubts about the person depicted.

Description[edit]

Depicted is a young woman as a half figure in a chair with an armrest[1] against a dark background. She stares slightly to the left. Personal features are light blond curls, the (rare) eye colour light grey, flat eyebrows and a snub nose — overall not representing the ideal of beauty. On her head she wears a balzo (a fashion invention of Isabella d'Este (prototypes before 1509[2]), but widely popular in northern Italy in the 1530s). Her clothes are dark, the sleeves green with patterns, a gold decorated shirt and a fur (probably lynx). The canvas is reputed to be trimmed on the left and right.

History[edit]

The painting passed from the Gonzaga collection in Mantua to the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, where it is listed as Catherine Cornaro ("Queen of Cyprus") in the inventory in 1659.[3]

An engraving of a copy of the painting shows an inscription "E Titiani prototypo P. P. Rubens exc. Isabella Estensis Francisisci Gonzagae March. Matovae uxor".[4] However, this inscription is three to four generations later and thus uncertain (cf. the mistaken baroque naming "Queen of Cyprus").

On the basis of this later inscription, Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle assigned the painting to a commission from the 60-year-old Isabella d'Este, which has been recorded in letters: Titian was to paint her portrait in 1534 on the basis of a portrait (now considered lost) by Francesco Francia in 1511.[5] Isabella commented on the portrait, completed in 1536, with "The portrait by Titian's hand is of such a pleasing type that we doubt that we were ever, at the age he represents, of such beauty that is contained in it."[6] The lost Francia original had already been painted 25 years earlier in absentia on the basis of oral descriptions and a third-party drawing. And the drawing is assumed to be a more than ten year older one by Leonardo da Vinci (1499/1500).[7] Isabella obviously wanted to be kept youthful and as an (ex-)beauty. Titian's other portrait of the aged Isabella d'Este (Isabella in Red, today only preserved by a Rubens copy in the same museum), had probably not pleased her, which is why this second commission is assumed.

In the 1930s, Wilhelm Suida and Leandro Ozzola opposed this naming as an idealisation of Isabella d'Este. Therefore, only artist and dating were documented as accepted by experts.[8] In the catalogue of the Isabella d'Este exhibition in Vienna (1994), the painting was still marketed as "by the hand of Titian, the 'greatest portrait painter of all time', as the portrait that clearly represents her".[9] The academic exhibition review again opposed: "but why, when engaged on so professional a face-lift, did Titian use so coarse a canvas?"[10]

Identity of the sitter[edit]

The identification of Isabella in black is uncertain. Nevertheless, the picture is uncritically circulated as the most famous portrait of Isabella d'Este, e.g. in books, probably because it is a Titian original (and the rest of the colour identifications are only copies).

Isabella d'Este was so famous as 'Prima donna del Mondo' and fashion icon that nobles asked to be allowed to copy her dressing.[11] After her death, depictions with balzo were uncritically identified (or marketed) as Isabella.[12] By the end of the last century, all colour identifications were withdrawn due to resulting contradictions.[13]

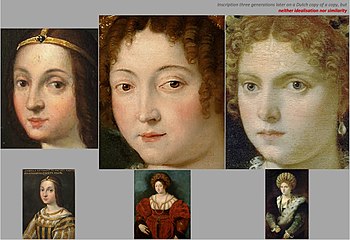

Exceptions are the three portraits in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which remain contradictory (see graphic at right): Ambras miniature [14] (anonymous 16th century), Isabella in Red (copy by Rubens c. 1606 after a lost original by Titian c. 1524-30), and Isabella in Black (Titian 1536).[15]

Points of discussion in the identification in Isabella in Black are the lack of similarities and the lack of beauty idealisation. At the same time, Isabella's successor Margherita Paleologa shows matching personal characteristics to Isabella in Black (incl. the stiff facial expression). And in 1531 her commission to Titian is also documented.[16]

Leandro Ozzola alternatively published La Bella (in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence) as Titian's portrait resp. idealisation after Francesco Francia.[17]

See also[edit]

Literature[edit]

- Francesco Valcanover: Das Gesamtwerk von Tizian. Rizzoli, Milan 1969.

- Sylvia Ferino-Pagden: La Prima Donna del Mondo – Isabella d’Este. exhibition catalogue KHM Vienna. Vienna 1994.

References[edit]

- ^ In Renaissance symbolism, the armrest is considered reserved for the current rulers, see e.g. Andrea Mantegna's fresco The Gonzaga Court in the Palazzo Ducale (Mantua).

- ^ Ferino-Pagden (1994), p. 112.

- ^ Valcanover (1969), p. 108.

- ^ Lucas Vorsterman after a Rubens copy of Titian's original, see Valcanover (1969), p. 108.

- ^ Valcanover (1969), p. 108.

- ^ Luzio, Alessandro. Arte Retrospettiva: I ritratti d'Isabella d'Este. In: Emporium. Vol. XI, No. 66, 1900, p. 432.

- ^ Cole, Bruce. Titian and the Idea of Originality in: The Craft of Art, University of Georgia Press, 1995, p. 100.

- ^ Valcanover (1969), p. 108.

- ^ Ferino-Pagden (1994), p. 111.

- ^ Jennifer Fletcher: Isabella d'Este, Vienna. In: The Burlington Magazine. 136, 1994, p. 399.

- ^ Even the Queen of France asked Isabella d‘Este for a doll to be dressed exactly like her, see Ferino-Pagden (1994), p. 112.

- ^ See the first three withdrawns with balzo in the next footnote.

- ^ See e.g.:

- Royal Collection, London (RCIN 405777): Giulio Romano Margherita Paleologa (1531) – picture

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (INV ГЭ-70): Paris Bordone Mother with son (1530s) – picture

- Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Milan (inv. 28): Bernardino Licinio Dama che regge un ritratto di figura maschile (1525-30) – picture

- Royal Collection, London (RCIN 405762): Lorenzo Costa Portrait of a lady with a Lapdog (c. 1500-05) – picture

- Currier Museum of Art, Manchester (inv. 1947.4): Lorenzo Costa Portrait of a woman (1506-10) – picture

- Louvre, Paris (inv 894): Giovanni Francesco Caroto Portrait de femme (c. 1505-10) – picture

- ^ picture

- ^ KHM Vienna: Inv GG 5081, Inv GG 1534, Inv. GG 83

- ^ Lisa Zeitz: Tizian, teurer Freund – Tizian und Federico Gonzaga, Kunstpatronage in Mantua im 16. Jahrhundert. Petersberg: Imhof, 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Leandro Ozzola: Isabella d’Este e Tiziano. In: Bolletino d’Arte del Ministero della pubblica istruzione. Rom 1931, Nr. 11, pp. 491–494; download: http://www.bollettinodarte.beniculturali.it/opencms/multimedia/BollettinoArteIt/documents/1407155929929_06_-_Ozzola_491.pdf