Cuniculture

Cuniculture is the agricultural practice of breeding and raising domestic rabbits as livestock for their meat, fur, or wool. Cuniculture is also employed by rabbit fanciers and hobbyists in the development and betterment of rabbit breeds and the exhibition of those efforts. Scientists practice cuniculture in the use and management of rabbits as model organisms in research. Cuniculture has been practiced all over the world since at least the 5th century.

History

[edit]Early husbandry

[edit]An abundance of ancient rabbits may have played a part in the naming of Spain. Phoenician sailors visiting its coast around the 12th century BC mistook the European rabbit for the familiar rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) of their homeland. They named their discovery i-shepan-ham, meaning 'land [or island] of hyraxes'. A theory exists (though it is somewhat controversial)[citation needed] that a corruption of this name used by the Romans became Hispania, the Latin name for the Iberian Peninsula.[1]

Domestication of the European rabbit rose slowly from a combination of game-keeping and animal husbandry. Among the numerous foodstuffs imported by sea to Rome during her domination of the Mediterranean were shipments of rabbits from Spain.[2]: 450 Romans also imported ferrets for rabbit hunting, and the Romans then distributed rabbits and the habit of rabbit keeping to the rest of Italy, to France, and then across the Roman Empire, including the British Isles.[3]: 42 Rabbits were kept in both walled areas as well as more extensively in game-preserves. In the British Isles, these preserves were known as warrens or garths, and rabbits were known as coneys, to differentiate them from the similar hares.[2]: 342–343 The term warren was also used as a name for the location where hares, partridges and pheasants were kept, under the watch of a game keeper called a warrener. In order to confine and protect the rabbits, a wall or thick hedge might be constructed around the warren, or a warren might be established on an island.[2]: 341–344 A warrener was responsible for controlling poachers and other predators and would collect the rabbits with snares, nets, hounds (such as greyhounds), or by hunting with ferrets.[2]: 343 With the rise of falconry, hawks and falcons were also used to collect rabbits and hares.[citation needed]

Domestication

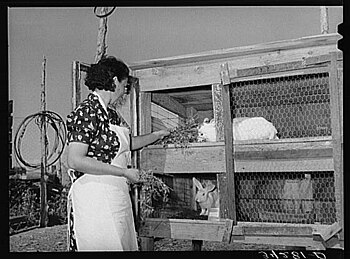

[edit]While under the warren system, rabbits were managed and harvested, but not domesticated. The practice of rabbit domestication also came from Rome. Christian monasteries throughout Europe and the Middle East kept rabbits since at least the 5th century. While rabbits might be allowed to wander freely within the monastery walls, a more common method was the employment of rabbit courts or rabbit pits. A rabbit court was a walled area lined with brick and cement, while a pit was similar, although less well-lined and more sunken.[2]: 347–350 Individual boxes or burrow-spaces could line the wall. Rabbits would be kept in a group in these pits or courts, and individuals collected when desired for eating or pelts. Rabbit keepers transferred rabbits to individual hutches or pens for easy cleaning, handling, or for selective breeding, as pits did not allow keepers to perform these tasks. Hutches or pens were originally made of wood, but are now more frequently made of metal in order to allow for better sanitation.[4]

Early breeds

[edit]

Rabbits were typically kept as part of the household livestock by peasants and villagers throughout Europe. Husbandry of the rabbits, including collecting weeds and grasses for fodder, typically fell to the children of the household or farmstead. These rabbits were largely 'common' or 'meat' rabbits and not of a particular breed, although regional strains and types did arise. Some of these strains remain as regional breeds, such as the Gotland of Sweden,[2]: 190 while others, such as the Land Kaninchen, a spotted rabbit of Germany, have become extinct.[2]: 15 Another rabbit type that standardized into a breed was the Brabancon, a meat rabbit of the region of Limbourg and what is now Belgium. Rabbits of this breed were bred for the Ostend port market, destined for London markets.[2]: 10 The development of the refrigerated shipping vessels led to the eventual collapse of the European meat rabbit trade, as the over-populated feral rabbits in Australia could now be harvested and sold.[5] The Brabancon is now considered extinct, although a descendant, the Dutch breed, remains a popular small rabbit for the pet trade.[2]: 9

In addition to being harvested for meat, properly prepared rabbit pelts were also an economic factor. Both wild rabbits and domestic rabbit pelts were valued, and it followed that pelts of particular rabbits would be more highly prized. As far back as 1631, price differentials were noted between ordinary rabbit pelts and the pelts of quality 'riche' rabbit in the Champagne region of France. (This regional type would go on to be recognized as the Champagne D'Argent, the 'silver rabbit of Champagne'.)[2]: 68

Among the earliest of the commercial breeds was the Angora, which some say may have developed in the Carpathian Mountains. They made their way to England, where during the rule of King Henry VIII, laws banned the exportation of long-haired rabbits as they were a national treasure. In 1723, long haired rabbits were imported to southern France by English sailors, who described the animals as originally coming from the Angora region of Turkey. Thus two distinct strains arose, one in France and one in England.[2]: 48–49

Expansion around the globe

[edit]European explorers and sailors took rabbits with them to new ports around the world, and brought new varieties back to Europe and England with them. With the second voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1494, European domestic livestock were brought to the New World.[6] Rabbits, along with goats and other hardy livestock, were frequently released on islands to produce a food supply for later ships.[2]: 151–152 The importations occasionally met with disastrous results, such as in the devastation in Australia. While cattle and horses were used across the socio-economic spectrum, and especially were concentrated among the wealthy, rabbits were kept by lower-income classes and peasants. This is reflected in the names given to the breeds that eventually arose in the colonized areas. From the Santa Duromo mountains of Brazil[citation needed] comes the Rustico, which is known in the United States as the Brazilian rabbit.[2]: 115 The Criollo rabbit comes from Mexico.[2]: 139

International commercial use

[edit]With the rise of scientific animal breeding in the late 1700s, led by Robert Bakewell[clarification needed] (among others), distinct livestock breeds were developed for specific purposes.[3]: 354–355

Rabbits were among the last of the domestic animals to have these principles applied to them, but the rabbit's rapid reproductive cycle allowed for marked progress towards a breeding goal in a short period of time. Additionally, rabbits could be kept on a small area, with a single person caring for over 300 breeding does on an acre of land.[2]: 120 Rabbit breeds were developed by individuals, cooperatives, and by national breeding centers. To meet various production goals, rabbits were exported around the world. One of the most notable import events was the introduction of the Belgian Hare breed of rabbit from Europe to the United States, beginning in 1888.[2]: 86 This led to a short-lived "boom" in rabbit breeding, selling, and speculation, when a quality breeding animal could bring $75 to $200. (For comparison, the average daily wage at the time was approximately $1.)[2]: 88 In 1900, a single animal-export company recorded 6,000 rabbits successfully shipped to the United States and Canada.[2]: 90

Science played another role in rabbit raising, this time with rabbits themselves as the tools used for scientific advancement. Beginning with Louis Pasteur's experiments in rabies in the later half of the nineteenth century, rabbits have been used as models to investigate various medical and biological problems, including the transmission of disease and protective antiserums.[3]: 377 Production of quality animals for meat sale and scientific experimentation has driven a number of advancements in rabbit husbandry and nutrition. While early rabbit keepers were limited to local and seasonal foodstuffs, which did not permit the maximization of production, health or growth, by 1930 researchers were conducting experiments in rabbit nutrition, similar to the experiments that had isolated vitamins and other nutritional components.[2]: 376 This eventually resulted in the development of various recipes for pelleted rabbit diets. Gradual refinement of diets has resulted in the widespread availability of pelleted feeds, which increase yield, reduce waste, and promote rabbit health, particularly maternal breeding health.[7]: 61–63

Rise of the fancy

[edit]The final leg of rabbit breeding—beyond meat, wool, fur, and laboratory use—was the breeding of 'fancy' animals as pets and curiosities. The term 'fancy' was originally applied to long-eared 'lop' rabbits, as they were the first type to be bred for exhibition.

Such rabbits were first admitted to agricultural shows in England in the 1820s, and in 1840 a club was formed for the promotion and regulation of exhibitions for "Fancy Rabbits".[2]: 228 In 1918, a new group formed to promote the fur breeds, originally just the Beveren and Havana breeds.[citation needed]

This club eventually expanded to become the British Rabbit Council.[2]: 441–443 Meanwhile, in the United States, clubs promoting various breeds were chartered in the 1880s, and the National Pet Stock Association was formed in 1910. This organization would become the American Rabbit Breeders Association.[2]: 425–429 Thousands of rabbit shows take place each year and are sanctioned in Canada, Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia and the United States by ARBA.[8]

With the advent of national-level organizations, rabbit breeders had a framework for establishing breeds and varieties utilizing recognized standards, and breeding for rabbit exhibitions began to expand rapidly. Such organizations and associations were also established across Europe—most notably in Germany, France, and Scandinavia[2]: 448 —allowing for the recognition of local breeds (many of which shared similar characteristics across national borders) and for the preservation of stock during disruptions such as World War I and World War II.[citation needed]

Closely overlapping with breeding for exhibition and for fur has been the breeding of rabbits for the pet trade. While rabbits have been kept as companions for centuries, the sale of rabbits as pets began to rise in the last half of the twentieth century. This may have been, in part, because rabbits require less physical space than dogs or cats, and do not require a specialized habitat like goldfish.[7]: 17 Several breeds of rabbit—such as the Holland Lop, the Polish, the Netherland Dwarf, and the Lionhead—have been specifically bred for the pet trade. Traits common to many popular pet breeds are small size, "dwarf" (or neotenic) features, plush or fuzzy coats, and an array of coat colors and patterns.[citation needed]

Modern farming

[edit]Outside of the exhibition circles, rabbit raising remained a small-scale but persistent household and farm endeavor, in many locations unregulated by the rules that governed the production of larger livestock. With the ongoing urbanization of populations worldwide, rabbit raising gradually declined, but saw resurgences in both Europe and North America during World War II, in conjunction with victory gardens.[9][10][11] Eventually, farmers across Europe and in the United States began to approach cuniculture with the same scientific principles as had already been applied to the production of grains, poultry, and hoofed livestock. National agriculture breeding stations were established to improve local rabbit strains and to introduce more productive breeds. National breeding centers focused on developing strains for production purposes, including meat, pelts, and wool.[2]: 119

These gradually faded from prominence in the United States,[12] but remained viable longer in Europe. Meanwhile, rabbit raising for local markets gained prominence in developing nations as an economical means of producing protein. Various aid agencies promote the use of rabbits as livestock.[citation needed] The animals are particularly useful in areas where women are limited in employment outside the household, because rabbits can be kept successfully in small areas.[13] These same factors have contributed to the increased popularity of rabbits as "backyard livestock" among locavores and homesteaders in more developed countries in North America and Europe. The addition of rabbits to the watchlist of endangered heritage breeds that is kept by The Livestock Conservancy has also led to increased interest from livestock conservationists. In contrast, throughout Asia (and particularly in China) rabbits are increasingly being raised and sold for export around the world.[14]

The World Rabbit Science Association (WRSA), formed in 1976, was established "to facilitate in all possible ways the exchange of knowledge and experience among persons in all parts of the world who are contributing to the advancement of the various branches of the rabbit industry". The WRSA organizes a world conference every four years.[15]

Present day (2000–present)

[edit]

Approximately 1.2 billion rabbits are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[16] In more recent years and in some countries, cuniculture has come under pressure from animal rights activists on several fronts. The use of animals, including rabbits, in scientific experiments has been subject to increased scrutiny in developed countries. Increasing regulation has raised the cost of producing animals for this purpose, and made other experimental options more attractive. Other researchers have abandoned investigations which required animal models.[17] Meanwhile, various rescue groups under the House Rabbit Society umbrella have taken an increasingly strident stance against any breeding of rabbits (even as food in developing countries) on the grounds that it contributes to the number of mistreated, unwanted or abandoned animals.[18]

The growth of homesteaders and smallholders has led to the rise of visibility of rabbit raisers in geographic areas where they have not been previously present. This has led to zoning conflicts over the regulation of butchering and waste management. Conflicts have also arisen with House Rabbit Society organizations as well as ethical vegetarians and vegans concerning the use of rabbits as meat and fur animals rather than as pets.[19] Conversely, many homesteaders cite concern with animal welfare in intensive farming of beef, pork and poultry as a significant factor in choosing to raise rabbits for meat.[citation needed]

In August 2022, an animal rights campaign group in the UK called "Shut Down T&S Rabbits" succeeded in closing down a network of rabbit meat and fur farms across the East Midlands region.[20]

The specific future direction of cuniculture is unclear, but does not appear to be in danger of disappearing in any particular part of the world. The variety of applications, as well as the versatile utility of the species, appears sufficient to keep rabbit raising a going concern in one aspect or another around the planet.[vague][citation needed]

Aspects of rabbit production

[edit]Meat rabbits

[edit]Rabbits have been raised for meat production in a variety of settings around the world. Smallholder or backyard operations remain common in many countries, while large-scale commercial operations are centered in Europe and Asia. For the smaller enterprise, multiple local rabbit breeds may be easier to use.

Many local, "rustico", landrace or other heritage type breeds may be used only in a specific geographic area. Sub-par or "cull" animals from other breeding goals (laboratory, exhibition, show, wool, or pet) may also be used for meat, particularly in smallholder operations.[citation needed]

Counterintuitively, the giant rabbit breeds are rarely used for meat production, due to their extended growth rates (which lead to high feed costs) and their large bone size (which reduces the percentage of their weight that is usable meat). Dwarf breeds, too, are rarely used, due to the high production costs, slow growth, and low offspring rate.[citation needed]

In contrast to the multitude of breeds and types used in smaller operations, breeds such as the New Zealand and the Californian, along with hybrids of these breeds, are most frequently utilized for meat in commercial rabbitries. The primary qualities of good meat-rabbit breeding stock are growth rate and size at slaughter, but also good mothering ability. Specific lines of commercial breeds have been developed that maximize these qualities – rabbits may be slaughtered as early as seven weeks and does of these strains routinely raise litters of 8 to 12 kits. Other breeds of rabbit developed for commercial meat production include the Florida White and the Altex.

Rabbit breeding stock raised in France is particularly popular with meat rabbit farmers internationally, some being purchased as far away as China in order to improve the local rabbit herd.[21]

Larger-scale operations attempt to maximize income by balancing land use, labor required, animal health, and investment in infrastructure. Specific infrastructure and strain qualities depend on the geographic area. An operation in an urban area may emphasize odor control and space utilization by stacking cages over each other with automatic cleaning systems that flush away faeces and urine. In rural sub-tropical and tropical areas, temperature control becomes more of an issue, and the use of air-conditioned buildings is common in many areas.[citation needed]

Breeding schedules for rabbits vary by individual operation. Prior to the development of modern balanced rabbit rations, rabbit breeding was limited by the nutrition available to the doe. Without adequate calories and protein, the doe would either not be fertile, would abort or resorb the foetuses during pregnancy, or would deliver small numbers of weak kits. Under these conditions, a doe would be re-bred only after weaning her last litter when the kits reached the age of two months. This allowed for a maximum of four litters per year. Advances in nutrition, such as those published by the USDA Rabbit Research Station, resulted in greater health for breeding animals and the survival of young stock. Likewise, offering superior, balanced nutrition to growing kits allowed for better health and less illness among slaughter animals. Current practices include the option of re-breeding the doe within a few days of delivery (closely matching the behavior of wild rabbits during the spring and early summer, when forage availability is at its peak.) This can result in up to eight or more litters annually. A doe of ideal meat-stock genetics can produce five times her body weight in fryers a year. Criticism of the more intensive breeding schedules has been made on the grounds that re-breeding that closely is excessively stressful for the doe. Determination of health effects of breeding schedules is made more difficult by the domestic rabbit's reproductive physiology – in contrast to several other mammal species, rabbits are more likely to develop uterine cancer when not used for breeding than when bred frequently.[citation needed]

In efficient production systems, rabbits can turn 20 percent of the proteins they eat into edible meat, compared to 22 to 23 percent for broiler chickens, 16 to 18 percent for pigs and 8 to 12 percent for beef; rabbit meat is more economical in terms of feed energy than beef.[22]

"Rabbit fryers" are rabbits that are between 70 and 90 days old, weighing 1.5 to 2.5 kilograms (3–5 lb) in live weight. "Rabbit roasters" are rabbits from 90 days to 6 months old, weighing 2.5–3.5 kg (5–8 lb) in live weight. "Rabbit stewers" are rabbits 6 months or older, weighing over 3.5 kg (8 lb). "Dark fryers" (i.e., any color other than white) typically garner a lower price than "white fryers" (also called "albino fryers"), because of the slightly darker tinge to the meat. (Purely pink carcasses are preferred by most consumers.) Dark fryers are also harder to de-hide (skin) than white fryers.[citation needed]

In the United States, white fryers garner the highest prices per pound of live weight. In Europe, however, a sizable market remains for the dark fryers that come from older and larger rabbits. In the kitchen, dark fryers are typically prepared differently from white fryers.[citation needed]

In 1990, the world's annual production of rabbit meat was estimated to be 1.5 million tonnes.[23] In 2014, the number was estimated at 2 million tonnes.[21] China is among the world's largest producers and consumers of rabbit meat, accounting for some 30% of the world's total consumption. Within China itself, rabbits are raised in many provinces, with most of the rabbit meat (about 70% of the national production, equaling some 420,000 tonnes annually) being consumed in the Sichuan Basin (Sichuan Province and Chongqing), where it is particularly popular.[21]

Well-known chef Mark Bittman wrote that domesticated rabbit "tastes like chicken", because both are "blank palettes on which we can layer whatever flavors we like".[24]

Wool rabbits and pelt rabbits

[edit]Wool rabbits

[edit]Rabbits such as the Angora, American Fuzzy Lop, and Jersey Wooly produce wool. However, since the American Fuzzy Lop and Jersey Wooly are both dwarf breeds, only the much larger Angora breeds such as the English Angora, Satin Angora, Giant Angora, and French Angora are used for commercial wool production. Their long fur is sheared, combed, or plucked (gently pulling loose hairs from the body during molting) and then spun into yarn used to make a variety of products. Angora sweaters can be purchased in many clothing stores and is generally mixed with other types of wool. In 2010, 70% of Angora rabbit wool was produced in China. Rabbit wool, generically called Angora, is 5 times warmer than sheep's wool.[citation needed]

Pelt rabbits

[edit]

A number of rabbit breeds have been developed with the fur trade in mind. Breeds such as the Rex, Satin, and Chinchilla are often raised for their fur. Each breed has fur characteristics and all have a wide range of colors and patterns. "Fur" rabbits are fed a diet especially balanced for fur production and the pelts are harvested when they have reached prime condition. Rabbit fur is widely used throughout the world. China imports much of its fur from Scandinavia (80%), and some from North America (5%), according to the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report CH7607.[citation needed]

Exhibition rabbits

[edit]Many rabbit keepers breed their rabbits for competition among other purebred rabbits of the same breed. Rabbits are judged according to the standards put forth by the governing associations of the particular country. These associations, being made up of people, may be distinctly political and reflect the preferences of particular persons on the governing boards. However, as mechanisms to preserve rare rabbit breeds, foster communication between breeders and encourage the education of the public, these organizations are invaluable. Examples include the American Rabbit Breeders Association and the British Rabbit Council.[citation needed]

Laboratory rabbits

[edit]

Rabbits have been and continue to be used in laboratory work such as production of antibodies for vaccines and research of human male reproductive system toxicology. Experiments with rabbits date back to Louis Pasteur's work in France in the 1800s. In 1972, around 450,000 rabbits were used for experiments in the United States, decreasing to around 240,000 in 2006.[25] The Environmental Health Perspective, published by the National Institute of Health, states, "The rabbit [is] an extremely valuable model for studying the effects of chemicals or other stimuli on the male reproductive system."[26] According to the Humane Society of the United States, rabbits are also used extensively in the study of asthma, stroke prevention treatments, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, and cancer.[citation needed]

Rabbit cultivation intersects with research in two ways: first, the keeping and raising of animals for testing of scientific principles. Some experiments require the keeping of several generations of animals treated with a particular drug, in order to fully appreciate the side effects of that drug. There is also the matter of breeding and raising animals for experiments. The New Zealand White is one of the most commonly used breeds for research and testing. Specific strains of the New Zealand White have been developed, with differing resistance to disease and cancers. Additionally, some experiments call for the use of 'specific pathogen free' animals, which require specific husbandry and intensive hygiene.[citation needed]

Animal rights activists generally oppose animal experimentation for all purposes, and rabbits are no exception.[improper synthesis?] The use of rabbits for the Draize test,[27] which is used for, amongst other things, testing cosmetics on animals, has been cited as an example of cruelty in animal research. Albino rabbits are typically used in the Draize tests because they have less tear flow than other animals and the lack of eye pigment make the effects easier to visualize.[citation needed] Rabbits in captivity are uniquely subject to rabbitpox, a condition that has not been observed in the wild.[citation needed]

Husbandry

[edit]Modern methods for housing domestic rabbits vary from region to region around the globe and by type of rabbit, technological or financial opportunities and constraints, intended use, number of animals kept, and the particular preferences of the owner or farmer. Various goals include maximizing number of animals per land unit (especially common in areas with high land values or small living areas) minimizing labor, reducing cost, increasing survival and health of animals, and meeting specific market requirements (such as for clean wool, or rabbits raised on pasture). Not all of these goals are complementary. Where the keeping of rabbits has been regulated by governments, specific requirements have been put in place. Various industries also have commonly accepted practices which produce predictable results for that type of rabbit product.[citation needed]

-

Armenia in 2009

-

Macedonia in 2013

-

France in 2015

-

Germany in 2017

-

Japan in 2016

-

India in 2016

-

Poland in 2009

-

Bangladesh in 2013

-

Hungary in 2015

Extensive cuniculture practices

[edit]Extensive cuniculture refers to the practice of keeping rabbits at a lower density and a lower production level than intensive culture. Specifically as relates to rabbits, this type of production was nearly universal prior to germ theory understanding of infectious parasites (especially coccidia) and the role of nutrition in prevention of abortion and reproductive loss. The most extensive rabbit "keeping" methods would be the harvest of wild or feral rabbits for meat or fur market, such as occurred in Australia prior to the 1990s. Warren-based cuniculture is somewhat more controlled, as the animals are generally kept to a specific area and a limited amount of supplemental feeding provided. Finally, various methods of raising rabbits with pasture as the primary food source have been developed. Pasturing rabbits within a fence (but not a cage), also known as colony husbandry, has not been commonly pursued due to the high death rate from weather and predators. More commonly (but still rare in terms of absolute numbers of rabbits and practitioners) is the practice of confining the rabbits to a moveable cage with an open or slatted floor so that the rabbits can access grass but still be kept at hand and protected from weather and predators. This method of growing rabbits does not typically result in an overall reduction for the need for supplemented feed. The growing period to market weight is much longer for grass fed rather than pellet fed animals, and many producers continue to offer small amounts of complete rations over the course of the growing period. Hutches or cages for this type of husbandry are generally made of a combination of wood and metal wire, made portable enough for a person to move the rabbits daily to fresh ground, and of a size to hold a litter of 6 to 12 rabbits at the market weight of 2 to 2.5 kg (4 to 5 lb). Protection from sun and driving rain are important health concerns, as is durability against predator attacks and the ability to be cleaned to prevent loss from coccidiosis.

Intensive cuniculture practices

[edit]

Intensive cuniculture is more focused, efficient, and time-sensitive, utilizing a greater density of animals and higher turnover. The labor required to produce each harvested hide, kilogram of wool, or market fryer—and the quality thereof—may be higher or lower than for extensive methods. Successful operations raising healthy rabbits that produce durable goods range from thousands of animals to less than a dozen. Simple hutches, kitchen floors, and even natural pits may provide shelter from the elements, while the rabbits are fed from the garden or given what can be gathered as they grow to produce a community's foodstuffs and textiles. Intensive cuniculture can also be practiced in an enclosed, climate controlled barn where rows of cages house robust rabbits eating pellets and treats before a daily health inspection or weekly weight check. Veterinary specialists and biosecurity may be part of large-scale operations, while individual rabbits in smaller setups may receive better—or worse—care.[citation needed]

Challenges to successful production

[edit]Specific challenges to the keeping of rabbits vary by specific practices. Losses from coccidiosis are much more common when rabbits are kept on the ground (such as in warrens or colonies) or on solid floors than when in wire or slat cages that keep rabbits elevated away from urine and faeces. Pastured rabbits are more subject to predator attack. Rabbits kept indoors at an appropriate temperature rarely suffer heat loss compared to rabbits housed outdoors in summer. At the same time, if rabbits are housed inside without adequate ventilation, respiratory disease can be a significant cause of illness and death. Production does on fodder are rarely able to raise more than 3 litters a year without heavy losses from deaths of weak kits, abortion, and fetal resorption, all related to poor nutrition and inadequate protein intake. In contrast, rabbits fed commercial pelleted diets can face losses related to low fiber intake.[citation needed]

Exhibition and fancier societies

[edit]

In the early 1900s, as animal fancy in general began to emerge, rabbit fanciers began to sponsor rabbit exhibitions and fairs in Western Europe and the United States. What became known as the "Belgian Hare Boom" began with the importation of the first Belgian Hares from England in 1888 and soon after the founding of the first rabbit club in America, the American Belgian Hare Association. From 1898 to 1901, many thousands of Belgian Hares were imported to America.[28] Today, the Belgian Hare is considered one of the rarest breeds, with less than 200 in the United States as reported in a recent survey.[29]

The American Rabbit Breeders Association (ARBA) was founded in 1910 and is the national authority on rabbit raising and rabbit breeds, having a uniform "Standard of Perfection", registration and judging system.[citation needed]

Conformation shows

[edit]Showing rabbits is an increasingly popular activity. Showing rabbits helps to improve the vigor and physical behavior of each breed through competitive selection. County fairs are common venues through which rabbits are shown in the United States. Rabbit clubs at local state and national levels hold many shows each year. Although only purebred animals are shown, a pedigree is not required to enter a rabbit in an ARBA-sanctioned show but is required to register the rabbit with ARBA. A rabbit must be registered in order to receive a Grand Champion certificate.[30] Children's clubs such as 4‑H also include rabbit shows, usually in conjunction with county fairs. The ARBA holds an annual national convention which has as many as 25,000 animals competing from all over the world. The mega show moves to a different city each year. The ARBA also sponsors youth programs for families as well as underprivileged rural and inner city children to learn responsible care and breeding of domestic rabbits.[citation needed]

Genetics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

The study of rabbit genetics is of interest to medical researchers, fanciers, and the fur and meat industries. Each of these groups has different needs for genetic information. In the biomedical research community and the pharmaceutical industry, rabbits genetics are important for producing antibodies, testing toxicity of consumer products, and in model organism research. Among rabbit fanciers and in the fiber and fur industry, the genetics of coat color and hair properties are paramount. The meat industry relies on genetics for disease resistance, feed conversion ratio, and reproduction potential.

The rabbit genome has been sequenced and is publicly available.[31] The mitochondrial DNA has also been sequenced.[32] In 2011, parts of the rabbit genome were re-sequenced in greater depth in order to expose variation within the genome.[33]

Gene linkage maps

[edit]

- Gene: du

- Pattern: Dutch

- Gene: B

- Color: Black (on white)

The early genetic research focused on linkage distance between various gross phenotypes using linkage analysis. Between 1924 and 1941, the relationship between c, y, b, du, En, l, r1, r2, A, dw, w, f, and br was established (phenotype is listed below).

- c: albino

- y: yellow fat

- du: Dutch coloring

- En: English coloring

- l: angora

- r1, r2: rex genes

- A: Agouti

- dw: dwarf gene

- w: wide intermediate-color band

- f: furless

- br: brachydactyly

The distance between these genes is as follows, numbered by chromosome. The format is gene1—distance—gene2. [34]

- c — 14.4 — y — 28.4 — b

- du — 1.2 — En — 13.1 — l

- r1 — 17.2 — r2

- A — 14.7 — dw — 15.4 — w

- f — 28.3 — br

Color genes

[edit]There are 11 color gene groups (or loci) in rabbits. They are A, B, C, D, E, En, Du, P, Si, V, and W. Each locus has dominant and recessive genes. In addition to the loci there are also modifiers, which modify a certain gene. These include the rufous modifiers, color intensifiers, and plus/minus (blanket/spot) modifiers. A rabbit's coat has either two pigments (pheomelanin for yellow, and eumelanin for dark brown) or no pigment (for an albino rabbit).[35][36]

Within each group, the genes are listed in order of dominance, with the most dominant gene first. In parentheses after the description is at least one example of a color that displays this gene.

- Gene: Enen

- Pattern: Broken

- Gene: D

- Color: Chocolate (on white)

- Gene: r1, r2

- Fur type: Rex

- Note: lower case are recessive and capital letters are dominant

- "A" represents the agouti locus (multiple bands of color on the hair shaft). The genes are:

- A: agouti ("wild color" or chestnut agouti, opal, chinchilla, etc.)

- a(t): tan pattern (otter, tan, silver marten)

- a: self- or non-agouti (black, chocolate)

- "B" represents the brown locus. The genes are:

- B: black (chestnut agouti, black otter, black)

- b: brown (chocolate agouti, chocolate otter, chocolate)

- "C" represents the color locus. The genes are:

- C: full color (black)

- c(ch3): dark chinchilla, removes yellow pigmentation (chinchilla, silver marten)

- c(ch2): medium (light) chinchilla, slight reduction in eumelanin creating a more sepia tone in the fur rather than black.

- c(ch1): light (pale) chinchilla (sable, sable point, smoke pearl, seal)

- c(h): color sensitive expression of color. Warmer parts of the body do not express color. Known as Himalayan, the body is white with extremities (points) colored in black, blue, chocolate or lilac. Pink eyes.

- c: albino (ruby-eyed white or REW)

- "D" represents the dilution locus. This gene dilutes black to blue and chocolate to lilac.[37]

- D: dense color (chestnut agouti, black, chocolate)

- d: diluted color (opal, blue or lilac)

- "E" represents the extension locus. It works with the 'A' and 'C' loci and rufous modifiers. When it is recessive, it removes most black pigment. The genes are:

- E(d): dominant black

- E(s): steel (black removed from tips of fur, which then appear golden or silver)

- E: normal

- e(j): Japanese brindling (harlequin), black and yellow pigment broken into patches over the body. In a broken color pattern, this results in Tricolor.

- e: most black pigment removed (agouti becomes red or orange, self- becomes tortoise)

- "En" represents the plus/minus (blanket/spot) color locus. It is incompletely dominant and results in three possible color patterns:

- EnEn: "Charlie" or a lightly marked broken with color on ears, on nose, and sparsely on body

- Enen: "Broken" with roughly even distribution of color and white

- enen: Solid color with no white areas

- "Du" represents the Dutch color pattern (the front of the face, the front part of the body, and rear paws are white; the rest of the rabbit has colored fur). The genes are:

- Du: absence of Dutch pattern

- du(d): Dutch (dark)

- du(w): Dutch (white)

- "V" represents the vienna white locus. The genes are:

- V: normal color

- Vv: Vienna carrier; carries blue-eyed white gene. May appear as a solid color, with snips of white on nose and/or front paws, or Dutch marked.

- v: vienna white (blue-eyed white or BEW)

- "Si" represents the silver locus. The genes are:

- Si: normal color

- si: silver color (silver, silver fox)

- "W" represents the middle yellow-white band locus and works with the agouti gene. The genes are:

- W: normal width of yellow band

- w: doubles yellow bandwidth (otter becomes tan, intensified red factors in Thrianta and Belgian Hare)

- "P" represents the OCA type II form of albinism. P is used because it is an integral P protein mutation. The genes are:

- P: normal color

- p: albinism mutation. Removes eumelanin and causes pink eyes. (Will change, for example, a chestnut agouti into a shadow)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anthon, Charles (1850). A System of Ancient and Mediæval Geography, for the Use of Schools and Colleges. New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Whitman, Bob D. (October 2004). Domestic Rabbits & Their Histories: Breeds of the World. Leawood KS: Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1585972753.

- ^ a b c Dunlop, Robert H.; Williams, David J. (1996). Veterinary Medicine: An Illustrated History. St Louis, MO: Mosby. ISBN 0-8016-3209-9.

- ^ Bennett, Bob (2009). Storey's Guide to Raising Rabbits: Breeds, Care, Housing. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. pp. 45–49. ISBN 978-1-60342-456-1.

- ^ Druett, Joan. "Chapter Eight — Living with embarrassment: the rabbit". Exotic Invaders. New Zealand Electronic Text Collection. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Virginia DeJohn (2004). Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-19-530446-6 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Templeton, George S. (1968). Domestic Rabbit Production. Danville, Illinois: The Interstate Printers & Publishers.

- ^ Hreiz, Jay (May–June 2012). "Domestic Rabbits". Domestic Rabbits. Vol. 40, no. 3. American Rabbit Breeders Association. p. 75.

- ^ Fish & Wildlife Service. "Press Release 14 Jan 1943" (PDF). Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Ashbrook, Frank G. (1943). How To Raise Rabbits for Food and Fur. New York: Orange Judd. pp. 23–28.

- ^ T., A. (1 April 1944). "Some Remarks on the History of the Rabbit in Australia". The Argus. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Beeman, Joseph. "Site of U.S. Rabbit Experimental Station". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Lebas, F. (1997). "9". The Rabbit: Husbandry, Health and Production. Rome: Food Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ^ Foster, M. (September 1996). "Structure of the Australian Rabbit Industry" (PDF). ABARE Report. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Lebas, Francois. "Constitution of the World Rabbit Science Association". World Rabbit Science Association. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ Abbott, Allison (2 August 2012). "Court Orders Temporary Closure of Dog-Breeding Facility". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11121. S2CID 159786021.

- ^ "HRS Activist Corner". House Rabbit Society. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Hottle, Molly. "23 Rabbits Stolen from Portland Meat Collective Farmer". The Oregonian. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Interview: How we shut down T&S rabbit breeders". September 2022.

- ^ a b c Geng, Olivia (12 June 2014). "French Rabbit Heads: The Newest Delicacy in Chinese Cuisine". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "FAO - The Rabbit - Husbandry, health and production". Archived from the original on 23 April 2015.

- ^ Lebas, F.; Coudert, P.; de Rochambeau, H.; Thébault, R. G. (1997). The Rabbit – Husbandry, Health and Production. FAO Animal Production and Health Series. Vol. 21. Rome, Italy: FAO – Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-103441-9. ISSN 1010-9021. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "How to Cook Everything: Braised Rabbit with Olives". 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ Kulpa-Eddy, Jodie; Snyder, Margaret; Stokes, William. "A review of trends in animal use in the United States (1972–2006)" (PDF). AATEX (14). Proc. 6th World Congress on Alternatives & Animal Use in the Life Sciences: 163–165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13.

- ^ Morton, Daniel (April 1988). "The use of rabbits in male reproductive toxicology". Environmental Health Perspectives. 77. National Institute of Health: 5–9. doi:10.2307/3430622. JSTOR 3430622. PMC 1474531. PMID 3383822.

- ^ Prinsen, M. K. (2006). "The Draize Eye Test and in vitro alternatives; a left-handed marriage?". Toxicology in Vitro. 20 (1): 78–81. Bibcode:2006ToxVi..20...78P. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.030. PMID 16055303.

- ^ "American Livestock Breeds Conservancy: Belgian Hare". Albc-usa.org. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- ^ "Hare Survey". Belgian Hare Club. Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- ^ "Official Show Rules". American Rabbit Breeders Association. 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Genome of Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit)". NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov. Washington, D.C.: United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Gissi, C.; Gullberg, A.; Arnason, U. (1998). "The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus". Genomics. 50 (2): 161–169. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5282. PMID 9653643.

- ^ Carneiro, M. (2011). "The Genetic Structure of Domestic Rabbits". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (6): 1801–1816. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr003. PMC 3695642. PMID 21216839.

- ^ Castle, W. E.; Sawin, P. B. (1941). "Genetic linkage in the rabbit". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 27 (11): 519–523. Bibcode:1941PNAS...27..519C. doi:10.1073/pnas.27.11.519. PMC 1078373. PMID 16588495.

- ^ Hinkle, Amy. "Rabbit [Color] Genes" (PDF). Amy's Rabbit Ranch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Hinkle, Amy. "[Rabbit Color] Genotypes" (PDF). Amy's Rabbit Ranch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Fontanesi, L.; Scotti, E.; Allain, D.; Dall'Olio, S. (2014). "A frameshift mutation in the melanophilin gene causes the dilute coat color in rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) breeds". Animal Genetics. 45 (2): 248–255. doi:10.1111/age.12104. PMID 24320228.

External links

[edit]- World Rabbit Science Association

- Russian Branch of the World Rabbit Science Association

- Belarusian Rabbit Breeders Public Association

- View the rabbit genome in Ensembl

- View the oryCun2 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser