Rafer Johnson

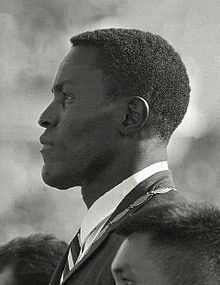

Johnson at the 1960 Olympics | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Rafer Lewis Johnson |

| Born | August 18, 1934 Hillsboro, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 2020 (aged 86) Sherman Oaks, California, U.S. |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (1.90 m) |

| Weight | 201 lb (91 kg) |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Thorsen (m. 1971) |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Athletics |

| Event | Decathlon |

| Club | Southern California Striders, Anaheim |

| Achievements and titles | |

| Personal best(s) | 100 m – 10.3 (1957) 220 yd – 21.0 (1956) 400 m – 47.9 (1956) 110 mH – 13.8 (1956) HJ – 1.89 m (1955) PV – 4.09 m (1960) LJ – 7.76 m (1956) SP – 16.75 m (1958) DT – 52.50 m (1960) JT – 76.73 m (1960) Decathlon – 8392 (1960)[1] |

Medal record | |

Rafer Lewis Johnson (August 18, 1934 – December 2, 2020) was an American decathlete and film actor. He was the 1960 Olympic gold medalist in the decathlon, having won silver in 1956. He had previously won a gold in the 1955 Pan American Games. He was the USA team's flag bearer at the 1960 Olympics and lit the Olympic cauldron at the Los Angeles Games in 1984.

In 1968, Johnson, football player Rosey Grier, and journalist George Plimpton tackled Sirhan Sirhan moments after he had fatally shot Robert F. Kennedy.

After he retired from athletics, Johnson turned to acting, sportscasting, and public service and was instrumental in creating the California Special Olympics. His acting career included appearances in The Sins of Rachel Cade (1961), the Elvis Presley film Wild in the Country (1961), Pirates of Tortuga (1961), None but the Brave (1965), two Tarzan films with Mike Henry, The Last Grenade (1970), Soul Soldier (1970), Roots: The Next Generations (1979), the James Bond film Licence to Kill (1989), and Think Big (1990).

Biography[edit]

Johnson was born in Hillsboro, Texas on August 18, 1934.[a][3][4] His family moved to Kingsburg, California, when he was aged nine.[5] For a while, they were the only black family in the town.[6] A versatile athlete, he played on Kingsburg High School's football, baseball and basketball teams. He was also elected class president in both junior high and high school.[6] The summer between his sophomore and junior years in high school (age 16), his coach Murl Dodson drove Johnson 24 miles (40 km) to Tulare and watched Bob Mathias compete in the 1952 U.S. Olympic decathlon trials.[7] Johnson told his coach, "I could have beaten most of those guys."[6] Dodson and Johnson drove back a month later to watch Mathias's victory parade. Weeks later, Johnson competed in a high school invitational decathlon and won the event. He also won the 1953 and 1954 California state high school decathlon meets.[7]

In 1954 as a freshman at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), his progress in the event was impressive; he broke the world record in his fourth competition.[6] He pledged Pi Lambda Phi fraternity, America's first non-sectarian fraternity, and was class president[6] at UCLA. In 1955, in Mexico City, he won the title at the Pan American Games.[3]

Johnson qualified for both the decathlon and the long jump events for the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne. However, he was hampered by an injury and forfeited his place in the long jump. Despite this handicap, he managed to take second place in the decathlon behind compatriot Milt Campbell. It would turn out to be his last defeat in the event.[6]

Due to injury, Johnson missed the 1957 and 1959 seasons (the latter due to a car accident), but he broke the world record in 1958 and again in 1960.[2] The crown to his career came at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. His most serious rival was Yang Chuan-Kwang (C. K. Yang) of Taiwan. Yang also studied at UCLA; the two trained together under UCLA track coach Elvin C. "Ducky" Drake and had become friends. In the decathlon, the lead swung back and forth between them. Finally, after nine events, Johnson led Yang by a small margin, but Yang was known to be better in the final event, the 1500 m. According to The Telegraph (UK), "legend has it" that Drake gave coaching to both men, with him advising Johnson to stay close to Yang and be ready for "a hellish sprint" at the end, and advising Yang to put as much distance between himself and Johnson before the final sprint as possible.[8][9]

Johnson ran his personal best at 4:49.7 and finished just 1.2 sec slower than Yang, winning the gold by 58 points with an Olympic record total of 8,392 points. Both athletes were exhausted and drained and came to a stop a few paces past the finish line leaning against each other for support.[8] With this victory, Johnson ended his athletic career.[3]

At UCLA, Johnson also played basketball under legendary coach John Wooden and was a starter for the Bruins on their 1958–59 team.[10] Wooden considered Johnson a great defensive player, but sometimes regretted holding back his teams early in his coaching career, remarking, "imagine Rafer Johnson on the [fast] break."[6]

Johnson was selected by the Los Angeles Rams in the 28th round (333rd overall) of the 1959 NFL Draft as a running back.[11]

While training for the 1960 Olympics, his friend Kirk Douglas told him about a part in Spartacus that Douglas thought might make him a star: the Ethiopian gladiator Draba, who refuses to kill Spartacus (played by Douglas) after defeating him in a duel. Johnson read for and got the role, but was forced to turn it down because the Amateur Athletic Union told him it would make him a professional and therefore ineligible for the Olympics. The role eventually went to another UCLA great, Woody Strode.[6] In 1960, Johnson began acting in motion pictures and working as a sportscaster. He made several film appearances, mostly in the 1960s. Johnson worked full-time as a sportscaster in the early 1970s. He was a weekend sports anchor on the local NBC affiliate in Los Angeles, KNBC, but seemed uncomfortable in that position and eventually moved on to other things.[12]

Johnson worked on the presidential election campaign of United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and on June 5, 1968, with the help of Rosey Grier, he apprehended Sirhan Sirhan immediately after Sirhan had assassinated Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Kennedy died the following day at Good Samaritan Hospital. Johnson discussed the experience in his autobiography, The Best That I Can Be (published in 1999 by Galilee Trade Publishing and co-authored with Philip Goldberg).[5]

Johnson served on the organizing committee for the first Special Olympics competition in Chicago in 1968, hosted by Special Olympics founder, Eunice Kennedy Shriver and the next year he led the founding of the California Special Olympics.[2] Johnson, along with a small group of volunteers, founded California Special Olympics in 1969 by conducting a competition at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for 900 individuals with intellectual disabilities. Following the first California Games in 1969, Johnson became one of the original members of the board of directors. The board worked together to raise funds and offer a modest program of swimming and track and field. In 1983, Rafer ran for President of the Board to increase Board participation, reorganize the staff to most effectively use each person's talents, and expand fundraising efforts. He was elected president and served in the capacity until 1992, when he was named chairman of the Board of Governors.[13]

Family[edit]

Johnson married Elizabeth Thorsen in 1971. They had two children and four grandchildren.[14]

Johnson's brother Jimmy is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame and his daughter Jennifer competed in beach volleyball at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney following her collegiate career at UCLA.[1] His son Joshua Johnson followed his father into track and field and had a podium finish in the javelin throw at the USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships.[15]

Johnson participated in the Art of the Olympians program.[16]

Rafer Johnson died after suffering a stroke on December 2, 2020, in Sherman Oaks, California. He was 86.[17]

Achievements[edit]

Johnson was named Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year in 1958[18] and won the James E. Sullivan Award as the top amateur athlete in the United States in 1960, breaking that award's color barrier. In 1962, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[19] He was chosen to ignite the Olympic Flame during the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, becoming the first Black athlete in Olympic history to do so.[6] In 1994, he was elected into the first class of the World Sports Humanitarian Hall of Fame.[12]

In 1998, Johnson was named one of ESPN's 100 Greatest North American Athletes of the 20th Century. In 2006, the NCAA named him one of the 100 Most Influential Student Athletes of the past 100 years.[20] On August 25, 2009, Governor Schwarzenegger and Maria Shriver announced that Johnson would be one of 13 California Hall of Fame inductees in The California Museum's yearlong exhibit. The induction ceremony was on December 1, 2009, in Sacramento, California.[21] Johnson was a member of The Pigskin Club of Washington, D.C. National Intercollegiate All-American Football Players Honor Roll.[22]

Rafer Johnson Junior High School in Kingsburg, California is named in his honor, as are Rafer Johnson Community Day School and Rafer Johnson Children's Center, both in Bakersfield, California.[23] The latter school, which has classes for special education students from the ages of birth-5, also puts on an annual Rafer Johnson Day. Every year Johnson himself spoke at the event and cheered on hundreds of students with special needs as they participated in a variety of track and field events.[24]

In 2010, Johnson received the Fernando Award for Civic Accomplishment from the Fernando Foundation and in 2011, he was inducted into the Bakersfield City School District Hall of Fame. Additionally, Rafer acted as the athletic advisor to Dan Guerrero, Director of Athletics at UCLA. He was Inducted into the Texas Track and Field Coaches Hall of Fame, Class of 2016.[25]

In November 2014, Johnson received the Athletes in Excellence Award from The Foundation for Global Sports Development, in recognition of his community service efforts and work with youth.[26]

In 2005, Johnson was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.) degree from Whittier College.[27]

Filmography[edit]

Actor[28][29][edit]

- The Sins of Rachel Cade (1960) – Kosongo. * "Sergeant Rutledge" (1960)- uncredited

- Wild in the Country (1961) – Davis

- Pirates of Tortuga (1961) – John Gammel

- None but the Brave (1965) – Pvt. Johnson

- Daniel Boone (1965, TV Series) – Rawls – S2/E4 "My Name Is Rawls"

- Tarzan and the Great River (1967) – Barcuma, Afro-Brazilian leader of the Jaguar Cult

- Tarzan and the Jungle Boy (1968) – Nagambi, villain who hinders Tarzan's search for the Jungle Boy

- The Last Grenade (1970) – Joe Jackson

- Soul Soldier (1970) – Pvt. Armstrong

- The Games (1970) – Commentator

- Mission Impossible (1971) – Jack Tully

- Roots: The Next Generations (1979)

- Licence to Kill (1989) – Mullens

- Think Big (1990) – Johnson

Production roles[edit]

- Billie (1965, technical advisor)

- The Black Six (1973, associate producer)

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Rafer Johnson". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Harris, Beth (December 2, 2020). "Rafer Johnson, Olympic champ who helped subdue RFK's assassin, dies at 86". The Mercury News. Associated Press. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c Martin, Jill; Almasy, Steve (December 2, 2020). "Rafer Johnson, 1960 Olympic decathlon champion, dies at 86". CNN.

- ^ Moritz, Charles (1962). Current Biography 1961. New York: H.W. Wilson. p. 222.

- ^ a b Johnson, Rafer (1998). The Best That I Can Be: an Autobiography. New York: Doubleday. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-3854-8760-3. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

I'm sure that in 1946 no one thought twice when they heard that another family named Johnson had moved into town; it was the most common name in Kingsburg.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Posnanski, Joe (August 2, 2010). "Rafer Johnson and the Power of 10". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Turrini, Joseph M. (2010). "Chapter 1 – The Purest of Rivalries: Rafer Johnson, C.K. Yang, and the 1960 Olympic Decathlon". In Wiggins, David K.; Rodgers, R . Pierre (eds.). Rivals: Legendary Matchups That Made Sports History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781610753494.

- ^ a b Henderson, Jon (June 26, 2012). "Great Olympic Moments: UCLA friends Rafer Johnson and Yang Chuan-kwang make decathlon history in 1960". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012.

- ^ Maraniss, David (2008). Rome 1960: The Olympics That Changed the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4165-3407-5.

At that moment, (Coach Elvin 'Ducky') Drake was like a master chess player competing against himself. He saw the whole board and was making the best moves for both sides.

- ^ Padilla, Mike (October 1, 2005). "Rafer Johnson — Olympic gold medalist and UCLA dad". UCLA Spotlight. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ "1959 Los Angeles Rams Draftees". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Rafer Johnson Timeline". LA84 Foundation. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Remembering Rafer Johnson". Special Olympics. December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (December 2, 2020). "Rafer Johnson, Winner of a Memorable Decathlon, Is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Jacobs and Washington on track for repeat in Paris – USA Champs Day Three. IAAF (2003-06-22). Retrieved on 2015-07-02.

- ^ "Be the best you can be: Rafer Johnson". Art of the Olympians. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (December 2, 2020). "Rafer Johnson, the Olympic gold medalist who helped bring the games to L.A., has died". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Sportsman of the Year". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "100 Most Influentical Student-Athletes". NCAA

- ^ "California Hall Fame Inductee Special Olympics Founder Editorial Stock Photo – Stock Image". Shutterstock Editorial. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "75th Annual Awards Dinner" (PDF). The Pigskin Club of Washington. Inc. February 8, 2013.

- ^ "Homepage". Rafer Johnson Jr. High. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Olympic champion Rafer Johnson had ties to Kern County, including being namesake of Bakersfield school". KGET News. December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Inductees". Texas Track and Field Coaches Association. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Fullerton, Laurie (November 21, 2014). "Eight Olympians, Paralympians Named Athletes In Excellence". Team USA. Archived from the original on December 12, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". Whittier College. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ "Rafer Johnson". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Rafer Johnson". TV Guide. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Maraniss, David (2008). Rome 1960: The Olympics That Changed The World. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-3408-2.

- Johnson, Rafer (1998). The Best That I Can Be: An Autobiography. Doubleday. ISBN 0-3854-8760-6.

External links[edit]

- Rafer Johnson at the Team USA Hall of Fame (archive July 20, 2023)

- Rafer Johnson at Olympics.com

- Rafer Johnson at Olympic.org (archived)

- Video clip from 1984 Summer Olympics, including Rafer Johnson lighting the Olympic Flame at Olympic.org

- Rafer Johnson at Olympedia

- Rafer Johnson at IMDb

- Rafer Johnson at Find a Grave

- 1934 births

- 2020 deaths

- American male decathletes

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Texas

- Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1955 Pan American Games

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1956 Summer Olympics

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1960 Summer Olympics

- World record setters in athletics (track and field)

- James E. Sullivan Award recipients

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in track and field

- Olympic silver medalists for the United States in track and field

- UCLA Bruins men's basketball players

- UCLA Bruins men's track and field athletes

- Track and field athletes from California

- Track and field athletes from Texas

- Olympic cauldron lighters

- People from Hillsboro, Texas

- Medalists at the 1960 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 1956 Summer Olympics

- Pan American Games gold medalists for the United States in athletics (track and field)

- People from Kingsburg, California

- Sportspeople from Fresno County, California

- American men's basketball players

- Track & Field News Athlete of the Year winners

- Medalists at the 1955 Pan American Games

- Burials at Pacific View Memorial Park