Richard Francis Burton

Richard Francis Burton | |

|---|---|

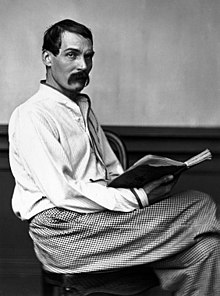

Burton in 1864 | |

| British consul in Fernando Pó | |

| British consul in Santos | |

| British consul in Damascus | |

| British consul in Trieste | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 March 1821 Torquay, Devon |

| Died | 20 October 1890 (aged 69) Trieste, Austria-Hungary |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse | |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Ruffian Dick |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Bombay Army |

| Years of service | 1842–1861 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | Crimean War |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George and Crimea Medal |

| Writing career | |

| Pen name |

|

| Notable works |

|

Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton, KCMG, FRGS (19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, writer, scholar and military officer.[1][2] He was famed for his travels and explorations in Asia, Africa, and South America, as well as his extensive knowledge of languages and cultures, speaking up to 29 different languages.[3]

Born in Torquay, Devon, Burton joined the Bombay Army as an officer in 1842, beginning an eighteen-year military career which including a brief stint in the Crimean War. He was subsequently engaged by the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) to explore the East African coast, where Burton along with John Hanning Speke led an expedition to discover the source of the Nile and became the first European known to have seen Lake Tanganyika. He later served as the British consul in Fernando Pó, Santos, Damascus and Trieste.[4] Burton was also a Fellow of the RGS and was awarded a knighthood in 1886.[5]

His best-known achievements include undertaking the Hajj to Mecca in disguise, translating One Thousand and One Nights and The Perfumed Garden, publishing the Kama Sutra in English and attempting to discover the source of the Nile. Although he abandoned his university studies, Burton became a prolific and erudite author and wrote numerous books and academic articles on subjects such as human behaviour, travel, falconry, fencing, sexual practices and ethnography.[6]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Richard Burton was born in Torquay, Devon on 19 March 1821; in his autobiography, he incorrectly claimed to have been born in the family home of Barham House in Elstree, Hertfordshire.[7][8] Burton was baptised on 2 September 1821 at Elstree Church in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire.[9] His father, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Netterville Burton, was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army's 36th (Herefordshire) Regiment of Foot. Joseph, through his mother's family, the Campbells of Tuam, was a first cousin of Henry Pearce Driscoll and Eliza Graves. Burton's mother, Martha Baker, was the daughter and co-heiress of Richard Baker, a wealthy Hertfordshire squire whom Burton was named after. He had two siblings, Maria Katherine Elizabeth Burton (who married Lieutenant-General Sir Henry William Stisted) and Edward Joseph Netterville Burton.[10]

Burton's family travelled extensively during his childhood and employed various tutors to educate him. In 1825, they moved to Tours in France. In 1829, Burton began a formal education at a preparatory school in Richmond Green, Surrey run by Reverend Charles Delafosse.[11] His family travelled between England, France, and Italy. Burton showed a talent to learn languages and quickly learned French, Italian, Neapolitan and Latin, as well as several dialects. During his youth, he allegedly had an sexual relationship with a Roma girl and learned the rudiments of the Romani language. The peregrinations of Burton's youth may have encouraged him to regard himself as an outsider for much of his life. As he later wrote, "Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but self expect applause".[12]

On 19 November 1840, he matriculated at Trinity College, Oxford. Before getting a room at the college, Burton lived for a short time in the house of William Alexander Greenhill, a doctor at the Radcliffe Infirmary. There, he met John Henry Newman, whose churchwarden was Greenhill. Despite his intelligence and ability, Burton was antagonised by his teachers and peers. During his first term, he allegedly challenged another student to a duel after the latter mocked Burton's moustache. Burton continued to gratify his love of languages by studying Arabic; he also spent his time learning falconry and fencing. In April 1842, Burton attended a steeplechase in a deliberate violation of college rules and subsequently told the college's authorities that students should be allowed to attend such events. Hoping to be merely rusticated, the punishment received by some less provocative students who had also visited the steeplechase, he was instead permanently expelled from the college.[13]

According to Ed Rice, speaking on Burton's university days, "He stirred the bile of the dons by speaking real—that is, Roman—Latin instead of the artificial type peculiar to England, and he spoke Greek Romaically, with the accent of Athens, as he had learned it from a Greek merchant at Marseilles, as well as the classical forms. Such a linguistic feat was a tribute to Burton's remarkable ear and memory, for he was only a teenager when he was in Italy and southern France."[14]

Bombay Army career

[edit]

In his own words, "fit for nothing but to be shot at for six pence a day",[15] Burton was commissioned into the Bombay Army at the behest of his former classmates in college who were already serving as officers there. He had hoped to fight in the First Anglo-Afghan War, but the conflict was over by the time Burton arrived in India. He was posted to the 18th Regiment of Bombay Native Infantry, which was stationed in Gujarat and under the command of General Charles James Napier.[16] While in India, he became a proficient speaker of Hindustani, Gujarati, Punjabi, Sindhi, Saraiki, Marathi, Persian and Arabic. His studies of Hindu culture had progressed to such an extent that "my Hindu teacher officially allowed me to wear the janeo".[17] Him Chand, his gotra teacher and a Nagar Brahmin, was possibly an apostate.[18] Burton had a documented interest and actively participated in the cultures and religions of India.[19] This was one of the many peculiar habits that set him apart from other British officers in India. While in the Bombay Army, he kept a large menagerie of tame monkeys in the hopes of learning their language, accumulating sixty "words".[20][14]: 56–65 He also earned the nickname "Ruffian Dick"[14]: 218 for his "demonic ferocity as a fighter and because he had fought in single combat more enemies than perhaps any other man of his time".[21]

According to Rice, "Burton now regarded the seven years in India as time wasted." Yet he had "already passed the official examinations in six languages and was studying two more and was eminently qualified." His religious experiences were varied, including attending Catholic services, becoming a Naga Brahmin, converting to Sikhism and Islam, and undergoing chilla for Qadiriyya Sufism. Regarding Burton's Muslim beliefs, Rice stated that "he was circumcised, and made a Muslim, and lived like a Muslim and prayed and practiced like one." Furthermore, Burton, "was entitled to call himself a hāfiz, one who can recite the Qur'ān from memory."[14]: 58, 67–68, 104–108, 150–155, 161, 164

First explorations and journey to Mecca

[edit]

Motivated by his love for adventure, Burton gained the approval of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) for an exploration of the Middle East, and, now at the rank of captain, received permission from the directors of the East India Company (EIC) to take leave from the Bombay Army. The seven years he spent in India gave Burton a familiarity with the customs and behaviour of Muslims and prepared him to attempt a Hajj to Mecca and Medina. He planned it whilst travelling disguised among Muslims in Sindh, and had laboriously prepared it by studying and practising Muslim culture, including undergoing circumcision to further lower the risk of being discovered.[22]

Burton's undertaking of the Hajj in 1853 was his realisation of "the plans and hopes of many and many a year... to study thoroughly the inner life of the Moslem." He donned the guise of a Persian mirza, and then a Sunni sheikh, doctor, magician and dervish, accompanied by an enslaved Indian boy named Nūr. In April, he travelled through Alexandria before reaching Cairo by May, where Burton stayed during Ramadan in June. He further equipped himself with a case for carrying the Quran, but which instead had three compartments for his watch, compass, money, penknife, pencils and numbered pieces of paper for taking notes.[4]

Burton travelled onwards with a group of nomads to Suez before sailing to Yambu and joining a caravan to Medina, where he arrived on 27 July. Departing Medina with a caravan on 31 August, Burton entered Mecca on 11 September, where he participated in the Tawaf. He travelled to Mount Arafat and participated in the stoning of the Devil, all the while taking notes on the Kaaba, its Black Stone and the Zamzam Well. Departing Mecca, he journeyed to Jeddah and then back to Cairo, returning to Army duty in Bombay. In India, Burton wrote his Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah, writing that "at Mecca there is nothing theatrical, nothing that suggests the opera, but all is simple and impressive... tending, I believe, after its fashion, to good."[14]: 179–225

Although Burton was not the first non-Muslim European to undertake the Hajj, with Ludovico di Varthema doing it in 1503 and Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1815,[23] his attempt is the most famous and the best documented of the period. He adopted various disguises including that of a Pashtun to account for any oddities in speech, but he still had to demonstrate an understanding of intricate Islamic traditions, and a familiarity with the minutiae of Eastern manners and etiquette. Burton's trek to Mecca was dangerous, and his caravan was attacked by bandits (a common experience at the time). As he put it, though "... neither Koran or Sultan enjoin the death of Jew or Christian intruding within the columns that note the sanctuary limits, nothing could save a European detected by the populace, or one who after pilgrimage declared himself an unbeliever".[24] The pilgrimage entitled him to the title of Hajji and to wear the green turban.[25][14]: 179–225

While back in India, Burton sat for the examination as an Arab linguist for the EIC. The examiner was Robert Lambert Playfair, who mistrusted Burton. As academic George Percy Badger knew Arabic well, Playfair asked Badger to oversee the exam. Having been told that Burton could be vindictive, and wishing to avoid any animosity should he fail, Badger declined. Eventually, Playfair conducted the tests; despite Burton's success in living like an Arab, Playfair recommended to the committee that Burton be failed. Badger later told Burton that "After looking [Burton's test] over, I sent them back to [Playfair] with a note eulogising your attainments and... remarking on the absurdity of the Bombay Committee being made to judge your proficiency inasmuch as I did not believe that any of them possessed a tithe of the knowledge of Arabic you did."[26]

Early explorations

[edit]

In May 1854, Burton travelled to Aden in preparation for an RGS-back expedition, which included John Hanning Speke, to Somaliland. The expedition lasted from 29 October 1854 to 9 February 1855, with much of its time spent in Zeila, where Burton was a guest of the town's governor Sharmarke Ali Saleh. Burton, assuming the disguise of an Arab merchant "Hajji Mirza Abdullah", awaited word that the road to Harar was safe. On 29 December, Burton met with Gerard Adan in the village of Sagharrah, and openly proclaimed himself as a British officer with a letter for the Emir of Harar. On 3 January 1855, Burton made it to Harar, and was graciously met by the Emir. He stayed in the city for ten days, officially a guest of the Emir but in reality his prisoner. Burton also investigated local landmarks in Harar; according to him, "A tradition exists that with the entrance of the first [white] Christian, Harar will fall." With Burton's entry, the tradition was broken.[14]: 219–220, 227–264 The journey back was plagued by lack of supplies, and Burton wrote that he would have died of thirst had he not seen desert birds and realized they would be near water. He made it back to Berbera on 31 January 1855.[27][14]: 238–256

Following this expedition, Burton prepared to set out in search of the source of the Nile, accompanied by Speke and a number of Africans porters and expedition guides. The Indian Navy schooner HCS Mahi transported them to Berbera on 7 April 1855. While the expedition was camped near Berbera, they was attacked by a group of Somali warriors from to Isaaq clan. The British estimated the number of attackers at 200. In the ensuing fight, Speke was wounded in eleven places before he managed to escape, while Burton was impaled with a javelin, the point entering one cheek and exiting the other, leaving a permanent scar; he was forced to escape with the weapon still transfixing his head. Burton subsequently wrote that the Somalis were a "fierce and turbulent race".[28] However, the failure of this expedition was viewed harshly by the British authorities, and a two-year investigation was set up to determine to what extent Burton was culpable for this disaster. While he was largely cleared of any blame, his career prospects were damaged. He described the attack in First Footsteps in East Africa (1856).[29][14]: 257–264

After recovering from his wounds in London, Burton travelled to Constantinople during the Crimean War, seeking an officer's commission. He received one from Major-General William Ferguson Beatson as the chief of staff for Beatson's Horse, an irregular Ottoman cavalry unit stationed in Gallipoli. Burton returned to England after an incident which implicated him as the instigator of a mutiny among the unit, damaging his reputation and disgracing Beatson.[14]: 265–271

Exploring the African Great Lakes

[edit]In 1856, the Royal Geographical Society funded another expedition for Burton and Speke, "and exploration of the then utterly unknown Lake regions of Central Africa." They would travel from Zanzibar to Ujiji along a caravan route established in 1825 by an Arab slave and ivory merchant. The Great Journey commenced on 5 June 1857 with their departure from Zanzibar, where they had stayed at the residence of Atkins Hamerton, the British consul,[30] their caravan consisting of Baluchi mercenaries led by Ramji, 36 porters, eventually a total of 132 persons, all led by the caravan leader Said bin Salim. From the beginning, Burton and Speke were hindered by disease, malaria, fevers, and other maladies, at times both having to be carried in a hammock. Pack animals died, and natives deserted, taking supplies with them. Yet, on 7 November 1857, they made it to Kazeh, and departed for Ujiji on 14 December. Speke wanted to head north, sure they would find the source of the Nile at what he later named Victoria Nyanza, but Burton persisted in heading west.[14]: 273–297

The expedition arrived at Lake Tanganyika on 13 February 1858. Burton was awestruck by the sight of the magnificent lake, but Speke, who had been temporarily blinded, was unable to see the body of water. By this point much of their surveying equipment was lost, ruined, or stolen, and they were unable to complete surveys of the area as well as they wished. Burton was again taken ill on the return journey; Speke continued exploring without him, making a journey to the north and eventually locating the great Lake Victoria, or Victoria Nyanza, on 3 August. Lacking supplies and proper instruments, Speke was unable to survey the area properly but was privately convinced that it was the long-sought source of the Nile. Burton's description of the journey is given in Lake Regions of Equatorial Africa (1860). Speke gave his own account in The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863).[31][14]: 298–312, 491–492, 500

Burton and Speke made it back to Zanzibar on 4 March 1859, and left on 22 March for Aden. Speke immediately boarded HMS Furious for London, where he gave lectures, and was awarded a second expedition by the Society. Burton arrived London on 21 May, discovering "My companion now stood forth in his new colours, and angry rival." Speke additionally published What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), while Burton's Zanzibar; City, Island, and Coast was eventually published in 1872.[14]: 307, 311–315, 491–492, 500

Burton then departed on a trip to the United States in April 1860, eventually making it to Salt Lake City on 25 August. There he studied Mormonism and met Brigham Young. Burton departed San Francisco on 15 November, for the voyage back to England, where he published The City of the Saints and Across the Rocky Mountains to California.[14]: 332–339, 492

Burton and Speke

[edit]

A prolonged public quarrel followed, damaging the reputations of both Burton and Speke. Some biographers have suggested that friends of Speke (particularly Laurence Oliphant) had initially stirred up trouble between the two.[32] Burton's sympathizers contend that Speke resented Burton's leadership role. Tim Jeal, who has accessed Speke's personal papers, suggests that it was more likely the other way around, Burton being jealous and resentful of Speke's determination and success. "As the years went by, [Burton] would neglect no opportunity to deride and undermine Speke's geographical theories and achievements".[33]

Speke had earlier proven his mettle by trekking through the mountains of Tibet, but Burton regarded him as inferior as he did not speak any Arabic or African languages. Despite his fascination with non-European cultures, some have portrayed Burton as an unabashed imperialist convinced of the historical and intellectual superiority of the white race, citing his involvement in the Anthropological Society of London, an organisation which supported of scientific racism.[34][35] Speke appears to have been kinder and less intrusive to the Africans they encountered, and reportedly fell in love with an African woman on a later expedition.[36]

The two men travelled home separately. Speke returned to London first and presented a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society, claiming Lake Victoria as the source of the Nile. According to Burton, Speke broke an agreement they had made to give their first public speech together. Apart from Burton's word, there is no proof that such an agreement existed, and most modern researchers doubt that it did. Tim Jeal, evaluating the written evidence, says the odds are "heavily against Speke having made a pledge to his former leader".[37] Speke undertook a second expedition, along with Captain James Grant and Sidi Mubarak Bombay, to prove that Lake Victoria was the true source of the Nile. Speke, in light of the issues he was having with Burton, had Grant sign a statement saying, among other things, "I renounce all my rights to publishing ... my own account [of the expedition] until approved of by Captain Speke or [the Royal Geographical Society]".[38]

On 16 September 1864, Burton and Speke were scheduled to debate the source of the Nile at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. On the day before the debate, Burton and Speke sat near each other in the lecture hall. According to Burton's wife, Speke stood up, said "I can't stand this any longer," and abruptly left the hall. That afternoon Speke went hunting on the nearby estate of a relative. He was discovered lying near a stone wall, felled by a fatal gunshot wound from his hunting shotgun. Burton learned of Speke's death the following day while waiting for their debate to begin. A jury ruled Speke's death an accident. An obituary surmised that Speke, while climbing over the wall, had carelessly pulled the gun after himself with the muzzle pointing at his chest and shot himself. Alexander Maitland, Speke's only biographer, concurs.[39]

Diplomatic service and scholarship (1861–1890)

[edit]

On 22 January 1861, Burton and Isabel Arundel married in a quiet Catholic ceremony although he did not adopt the Catholic faith at this time. Shortly after this, the couple were forced to spend some time apart when he formally entered the Diplomatic Service as consul on the island of Fernando Po, now Bioko in Equatorial Guinea. This was not a prestigious appointment; because the climate was considered extremely unhealthy for Europeans, Isabel could not accompany him. Burton spent much of this time exploring the coast of West Africa, documenting his findings in Abeokuta and The Cameroons Mountains: An Exploration (1863), and A Mission to Gelele, King of Dahome (1864). He described some of his experiences, including a trip up the Congo River to the Yellala Falls and beyond, in his 1876 book Two trips to gorilla land and the cataracts of the Congo.[40][14]: 349–381, 492–493

The couple were reunited in 1865 when Burton was transferred to Santos in Brazil. Once there, Burton travelled through Brazil's central highlands, canoeing down the São Francisco River from its source to the falls of Paulo Afonso.[41] He documented his experiences in The Highlands of Brazil (1869).[14] In 1868 and 1869, he made two visits to the war zone of the Paraguayan War, which he described in his Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay (1870).[42] In 1868, he was appointed as the British consul in Damascus, an ideal post for someone with Burton's knowledge of the region and customs.[43] According to Ed Rice, "England wanted to know what was going on in the Levant," another chapter in The Great Game. Yet, the Turkish governor Mohammed Rashid 'Ali Pasha, feared anti-Turkish activities, and was opposed to Burton's assignment.[14]: 395–399, 402, 409

In Damascus, Burton made friends with Abdelkader al-Jazairi, while Isabel befriended Jane Digby, calling her "my most intimate friend." Burton also met Charles F. Tyrwhitt-Drake and Edward Henry Palmer, collaborating with Drake in writing Unexplored Syria (1872).[14]: 402–410, 492 However, the area was in some turmoil at the time with considerable tensions between the Christian, Jewish and Muslim populations. Burton did his best to keep the peace and resolve the situation, but this sometimes led him into trouble. On one occasion, he claims to have escaped an attack by hundreds of armed horsemen and camel riders sent by Mohammed Rashid Pasha, the Governor of Syria. He wrote, "I have never been so flattered in my life than to think it would take three hundred men to kill me."[44] Burton eventually suffered the enmity of the Greek Christian and Jewish communities. Then, his involvement with the Sházlis, a Sufi Muslim order among whom was a group that Burton called "Secret Christians longing for baptism," which Isabel called "his ruin." He was recalled in August 1871, prompting him to send a telegram to Isabel: "I am recalled. Pay, pack, and follow at convenience."[14]: 412–415

Burton was reassigned in 1872 to the port city of Trieste in Austria-Hungary.[45] A "broken man", Burton was never particularly content with this post, but it required little work, was far less dangerous than Damascus (as well as less exciting), and allowed him the freedom to write and travel.[46] In 1863, Burton co-founded the Anthropological Society of London with Dr. James Hunt. In Burton's own words, the main aim of the society (through the publication of the periodical Anthropologia) was "to supply travellers with an organ that would rescue their observations from the outer darkness of manuscript and print their curious information on social and sexual matters". On 13 February 1886, Burton was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) by Queen Victoria.[47]

He wrote a number of travel books in this period that were not particularly well received. His best-known contributions to literature were those considered risqué or even pornographic at the time, which were published under the auspices of the Kama Shastra society. These books include The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana (1883) (popularly known as the Kama Sutra), The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885) (popularly known as The Arabian Nights), The Perfumed Garden of the Shaykh Nefzawi (1886) and The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night (seventeen volumes 1886–98). Published in this period but composed on his return journey from Mecca, The Kasidah[12] has been cited as evidence of Burton's status as a Bektashi Sufi. Deliberately presented by Burton as a translation, the poem and his notes and commentary on it contain layers of Sufic meaning that seem to have been designed to project Sufi teaching in the West.[48] "Do what thy manhood bids thee do/ from none but self expect applause;/ He noblest lives and noblest dies/ who makes and keeps his self-made laws" is The Kasidah's most-quoted passage. As well as references to many themes from Classical Western myths, the poem contains many laments that are accented with fleeting imagery such as repeated comparisons to "the tinkling of the Camel bell" that becomes inaudible as the animal vanishes in the darkness of the desert.[49]

Other works of note include a collection of Hindu tales, Vikram and the Vampire (1870); and his uncompleted history of swordsmanship, The Book of the Sword (1884). He also translated The Lusiads, the Portuguese national epic by Luís de Camões, in 1880 and, the next year, wrote a sympathetic biography of the poet and adventurer. The book The Jew, the Gipsy and el Islam was published posthumously in 1898 and was controversial for its criticism of Jews and for its assertion of the existence of Jewish human sacrifices. Burton's investigations into this had provoked hostility from the Jews of Damascus. The manuscript of the book included an appendix discussing the topic in more detail, but by the decision of his widow, it was not included in the book when published.[4]

Death

[edit]

Burton died in Trieste early on the morning of 20 October 1890 of a heart attack. His wife Isabel persuaded a priest to perform the last rites, although Burton was not a Catholic, and this action later caused a rift between Isabel and some of Burton's friends. It has been suggested that the death occurred very late on 19 October and that Burton was already dead by the time the last rites were administered. On his religious views, Burton called himself an atheist, stating he was raised in the Church of England which he said was "officially (his) church".[50]

Isabel never recovered from the loss. After his death she burned many of her husband's papers, including journals and a planned new translation of The Perfumed Garden to be called The Scented Garden, for which she had been offered six thousand guineas and which she regarded as his "magnum opus". She believed she was acting to protect her husband's reputation, and that she had been instructed to burn the manuscript of The Scented Garden by his spirit, but her actions were controversial.[51] However, a substantial quantity of his written materials have survived, and are held by the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, including 21 boxes of his manuscripts, 24 boxes of correspondence, and other material.[52]

Isabel wrote a biography in praise of her husband.[53]

The couple are buried in a tomb in the shape of a Bedouin tent, designed by Isabel,[54] in the cemetery of St Mary Magdalen Roman Catholic Church Mortlake in southwest London.[55] The coffins of Sir Richard and Lady Burton can be seen through a window at the rear of the tent, which can be accessed via a short fixed ladder. Next to the lady chapel in the church there is a memorial stained-glass window to Burton, also erected by Isabel; it depicts Burton as a medieval knight.[56] Burton's personal effects and a collection of paintings, photographs and objects relating to him are in the Burton Collection at Orleans House Gallery, Twickenham.[57] Among these is a small quartz stone from Mesopotamia, inscribed in supposed Kufic script, which has thus far resisted decipherment by experts.[58][59]

Kama Shastra Society

[edit]Burton had long had an interest in sexuality and some erotic literature. However, the Obscene Publications Act of 1857 had resulted in many jail sentences for publishers, with prosecutions being brought by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. Burton referred to the society and those who shared its views as Mrs Grundy. A way around this was the private circulation of books amongst the members of a society. For this reason Burton, together with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, created the Kama Shastra Society to print and circulate books that would be illegal to publish in public.[60]

One of the most celebrated of all his books is his translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (commonly called The Arabian Nights in English after early translations of Antoine Galland's French version) in ten volumes (1885), with seven further volumes being added later. The volumes were printed by the Kama Shastra Society in a subscribers-only edition of one thousand with a guarantee that there would never be a larger printing of the books in this form. The stories collected were often sexual in content and were considered pornography at the time of publication. In particular, the Terminal Essay in volume 10 of the Nights contained a 14,000-word essay entitled "Pederasty" (Volume 10, section IV, D), at the time a synonym for homosexuality (as it still is, in modern French). This was and remained for many years the longest and most explicit discussion of homosexuality in any language. Burton speculated that male homosexuality was prevalent in an area of the southern latitudes named by him the "Sotadic zone".[61]

Perhaps Burton's best-known book is his translation of The Kama Sutra. It is untrue that he was the translator since the original manuscript was in ancient Sanskrit, which he could not read. However, he collaborated with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot on the work and provided translations from other manuscripts of later translations. The Kama Shastra Society first printed the book in 1883 and numerous editions of the Burton translation are in print to this day.[60]

His English translation from a French edition of the Arabic erotic guide The Perfumed Garden was printed as The Perfumed Garden of the Cheikh Nefzaoui: A Manual of Arabian Erotology (1886). After Burton's death, Isabel burnt many of his papers, including a manuscript of a subsequent translation, The Scented Garden, containing the final chapter of the work, on pederasty. Burton all along intended for this translation to be published after his death, to provide an income for his widow.[62]

By the end of his life, Burton had mastered at least 26 languages – or 40, if distinct dialects are counted.[63]

1. English

2. French

3. Occitan (Gascon/Béarnese dialect)

4. Italian5. Romani

6. Latin

7. Greek

8. Saraiki

9. Hindustani

- a. Urdu

10. Sindhi

11. Marathi

12. Arabic

13. Persian (Farsi)

14. Pushtu

15. Sanskrit

16. Portuguese

17. Spanish

18. German

19. Icelandic

20. Swahili

21. Amharic

22. Fan

23. Egba

24. Asante

25. Hebrew

26. Aramaic

27. Many other West African & Indian dialects

Scandals

[edit]

Burton's writings are unusually open and frank about his interest in sex and sexuality. His travel writing is often full of details about the sexual lives of the inhabitants of areas he travelled through. Burton's interest in sexuality led him to make measurements of the lengths of the penises of male inhabitants of various regions, which he includes in his travel books. He also describes sexual techniques common in the regions he visited, often hinting that he had participated, hence breaking both sexual and racial taboos of his day. Many people at the time considered the Kama Shastra Society and the books it published scandalous.[64]

Biographers disagree on whether or not Burton ever experienced homosexual sex (he never directly acknowledges it in his writing). Rumours began in his army days when Charles James Napier requested that Burton go undercover to investigate a male brothel reputed to be frequented by British soldiers. It has been suggested that Burton's detailed report on the workings of the brothel led some to believe he had been a customer.[65] There is no documentary evidence that such a report was written or submitted, nor that Napier ordered such research by Burton, and it has been argued that this is one of Burton's embellishments.[66]

A story that haunted Burton up to his death (recounted in some of his obituaries) was that, during his journey to Mecca disguised as a Muslim, he came close to being discovered one night when he lifted his robe to urinate rather than squatting as an Arab would. It was said that he was seen by an Arab and, to avoid exposure, killed him. Burton denied this, pointing out that killing the boy would almost certainly have led to his being discovered as an impostor. Burton became so tired of denying this accusation that he took to baiting his accusers, although he was said to enjoy the notoriety and even once laughingly claimed to have done it.[67][68] A doctor once asked him: "How do you feel when you have killed a man?", Burton retorted: "Quite jolly, what about you?". When asked by a priest about the same incident Burton is said to have replied: "Sir, I'm proud to say I have committed every sin in the Decalogue."[69] Stanley Lane-Poole, a Burton detractor, reported that Burton "confessed rather shamefacedly that he had never killed anybody at any time."[68]

These allegations coupled with Burton's often irascible nature were said to have harmed his career and may explain why he was not promoted further, either in army life or in the diplomatic service. As an obituary described: "...he was ill fitted to run in official harness, and he had a Byronic love of shocking people, of telling tales against himself that had no foundation in fact."[70] Ouida reported: "Men at the FO [Foreign Office] ... used to hint dark horrors about Burton, and certainly justly or unjustly he was disliked, feared and suspected ... not for what he had done, but for what he was believed capable of doing."[71]

Sotadic Zone

[edit]

Burton theorized about the existence of a Sotadic Zone in the closing essay of his English translation of The Arabian Nights (1885–1886).[72][73] He asserted that there exists a geographic-climatic zone in which sodomy and pederasty (sexual intimacy between older men and young pubescent/adolescent boys) are endemic,[72][73] prevalent,[72][73] and celebrated among the indigenous inhabitants and within their cultures.[73] The name derives from Sotades,[73] a 3rd-century BC Ancient Greek poet who was the chief representative of a group of Ancient Greek writers of obscene, and sometimes pederastic, satirical poetry; these homoerotic verses are preserved in the Greek Anthology, a collection of poems spanning the Classical and Byzantine periods of Greek literature.

Burton first advanced his Sotadic Zone concept in the "Terminal Essay",[74] contained in Volume 10 of his English translation of The Arabian Nights, which he called The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, published in England in 1886.[72][75]

In popular culture

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- In the short story "The Aleph" (1945) by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, a manuscript by Burton is discovered in a library. The manuscript contains a description of a mirror in which the whole universe is reflected.

- The Riverworld series of science fiction novels (1971–83) by Philip José Farmer has a fictional and resurrected Burton as a primary character.

- William Harrison's Burton and Speke is a 1984 novel about the two friends/rivals.[76]

- The World Is Made of Glass: A Novel by Morris West[77] tells the story of Magda Liliane Kardoss von Gamsfeld in consultation with Carl Gustav Jung; Burton is mentioned on pp. 254–7 and again on p. 392.

- Der Weltensammler[78] by the Bulgarian-German writer Iliya Troyanov is a fictional reconstruction of three periods of Burton's life, focusing on his time in India, his pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca, and his explorations with Speke.

- Burton is the main character in the "Burton and Swinburne" steampunk series by Mark Hodder (2010–2015): The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack; The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man; Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon; The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi; The Return of the Discontinued Man; and The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats. These novels depict an alternate world where Queen Victoria was killed early in her reign due to the inadvertent actions of a time-traveler acting as Spring-Heeled Jack, with a complex constitutional revision making Albert King in her place.

- Though not one of the primary characters in the series, Burton plays an important historical role in the Area 51 series of books by Bob Mayer (written under the pen name Robert Doherty).

- Burton and his partner Speke are recurrently mentioned in one of Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires, the 1863 novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, as the voyages of Kennedy and Ferguson are attempting to link their expeditions with those of Heinrich Barth in west Africa.

- In the novel The Bookman's Promise (2004) by John Dunning, the protagonist buys a signed copy of a rare Burton book, and from there Burton and his work are major elements of the story. A section of the novel also fictionalizes a portion of Burton's life in the form of recollections of one of the characters.

- Burton and Speke appear as characters in the historical novel The Romantic by William Boyd (2022).

Drama

[edit]- In the BBC mini-series The Search for the Nile (1971), Burton is portrayed by actor Kenneth Haigh.

- The film Mountains of the Moon (1990) (starring Patrick Bergin as Burton) relates the story of the Burton-Speke exploration and subsequent controversy over the source of the Nile. The script was based on Harrison's novel.

- In the Canadian film Zero Patience (1993), Burton is portrayed by John Robinson as having had "an unfortunate encounter" with the Fountain of Youth and is living in present-day Toronto. Upon discovering the ghost of the famous Patient Zero, Burton attempts to exhibit the finding at his Hall of Contagion at the Museum of Natural History.

- In the American TV show The Sentinel, a monograph by Sir Richard Francis Burton is found by one of the main characters, Blair Sandburg, and is the origins for his concept of Sentinels and their roles in their respective tribes.

Film documentaries

[edit]- In The Victorian Sex Explorer, Rupert Everett documents Burton's travels. Part of the Channel Four (UK) 'Victorian Passions' season. First Broadcast on 9 June 2008.

Chronology

[edit]

Works and correspondence

[edit]Burton published over 40 books and countless articles, monographs and letters. A great number of his journal and magazine pieces have never been catalogued. Over 200 of these have been collected in PDF facsimile format at burtoniana.org.[79]

Brief selections from a variety of Burton's writings are available in Frank McLynn's Of No Country: An Anthology of Richard Burton (1990; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ de la Fuente, Ariel (31 October 2023). "Sir Richard Burton's Orientalist Erotica". Borges, Desire, and Sex. Liverpool University Press. pp. 84–108. doi:10.2307/j.ctvhn09p9.9. ISBN 9781786941503. JSTOR j.ctvhn09p9.9. S2CID 239794503.

- ^ "Sir Richard Francis Burton". freemasonry.bcy.ca. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Young, S. (2006). "India". Richard Francis Burton: Explorer, Scholar, Spy. New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 16–26. ISBN 9780761422228.

- ^ a b c Paxman, Jeremy (1 May 2015). "Richard Burton, Victorian explorer". www.ft.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Historic Figures: Sir Richard Burton". BBC. Retrieved 7 April 2017

- ^ Burton, I.; Wilkins, W. H. (1897). The Romance of Isabel Lady Burton. The Story of Her Life. New York: Dodd Mead & Company. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Lovell, p. 1.

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 37 .

- ^ Page, William (1908). A History of the County of Hertford. Constable. vol. 2, pp. 349–351. ISBN 978-0-7129-0475-9. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 38 .

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 52 .

- ^ a b Burton, R. F. (1911). "Chapter VIII". The Kasîdah of Hâjî Abdû El-Yezdî (Eight ed.). Portland: Thomas B. Mosher. pp. 44–51.

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 81 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Rice, Ed (1990). Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: the secret agent who made the pilgrimage to Mecca, discovered the Kama Sutra, and brought the Arabian nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 22. ISBN 978-0684191379.

- ^ Falconry in the Valley of the Indus, Richard F. Burton (John Van Voorst 1852) page 93.

- ^ Ghose, Indira (January 2006). "Imperial Player: Richard Burton in Sindh". In Youngs, Tim (ed.). Travel Writing in the Nineteenth Century. Anthem Press. pp. 71–86. doi:10.7135/upo9781843317692.005. ISBN 9781843317692. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ Burton (1893), Vol. 1, p. 123.

- ^ Rice, Edward. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton (1991). p. 83.

- ^ In 1852, a letter from Burton was published in The Zoist: "Remarks upon a form of Sub-mesmerism, popularly called Electro-Biology, now practised in Scinde and other Eastern Countries", The Zoist: A Journal of Cerebral Physiology & Mesmerism, and Their Applications to Human Welfare, Vol.10, No.38, (July 1852), pp.177–181.

- ^ Lovell, p. 58.

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, pp. 119–120 .

- ^ Seigel, J. (2015). Between Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary Lives. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812247619.

- ^ Leigh, R. "Ludovico di Varthema". Discoverers Web. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Burton, R. (1924). Penzer, N. M. (ed.). Selected Papers on Anthropology, Travel, and Exploration. London <publisher=A. M. Philpot.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Burton, R. F. (1855). A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah. London: Tylston and Edwards.

- ^ Lovell, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Burton, R., Speke, J. H., Barker, W. C. (1856). First footsteps in East Africa or, An Exploration of Harar. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ In last of a series of dispatches from Mogadishu, Daniel Howden reports on the artists fighting to keep a tradition alive, The Independent, dated Thursday, 2 December 2010.

- ^ Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 449–458.

- ^ Moorehead, Alan (1960). The White Nile. London: Hamish Hamilton. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Speke, John Hanning. "The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile". wollamshram.ca. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Carnochan, pp. 77–78 cites Isabel Burton and Alexander Maitland

- ^ Jeal, p. 121.

- ^ Jeal, p. 322.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 135.

- ^ Jeal, pp. 129, 156–166.

- ^ Jeal, p. 111.

- ^ Lovell, p. 341.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 123.

- ^ Richard Francis Burton, Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo, 2 vols. (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, 1876).

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 200 .

- ^ Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay, the Preface.

- ^ "No. 23447". The London Gazette. 4 December 1868. p. 6460.

- ^ Burton (1893), Vol. 1, p. 517.

- ^ "No. 23889". The London Gazette. 20 September 1872. p. 4075. [dead link]

- ^ Wright, Thomas (1 January 1906). The Life of Sir Richard Burton. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465550132 – via Google Books.

- ^ "No. 25559". The London Gazette. 16 February 1886. p. 743.

- ^ The Sufis by Idries Shah (1964) p. 249ff

- ^ The Kasidah of Haji Abdu El-Yezdi. 1880.

- ^ Wright (1906) "Some three months before Sir Richard's death," writes Mr. P. P. Cautley, the Vice-Consul at Trieste, to me, "I was seated at Sir Richard's tea table with our clergy man, and the talk turning on religion, Sir Richard declared, 'I am an atheist, but I was brought up in the Church of England, and that is officially my church.'"

- ^ Wright (1906), vol. 2, pp. 252–254 .

- ^ "Sir Richard Francis Burton papers, 1846-2003 (bulk 1846-1939)". Huntington Library. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Burton (1893)

- ^ Cherry, B.; Pevsner, N. (1983). The Buildings of England – London 2: South. London: Penguin Books. p. 513. ISBN 978-0140710472.

- ^ Burton, Isabel (10 December 1890). "Sir Richard Burton". Morning Post. p. 2 – via British Library Newspapers.

- ^ Boyes, Valerie & Wintersinger, Natascha (2014). Encountering the Uncharted and Back – Three Explorers: Ball, Vancouver and Burton. Museum of Richmond. pp. 9–10.

- ^ De Novellis, Mark. "More about Richmond upon Thames Borough Art Collection". Art UK. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ "What am I?". Orleans House Gallery. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Randall, T.K. (20 October 2018). "Ancient talisman inscription remains a mystery". Unexplained mysteries: Archaeology & History. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ a b Ben Grant, "Translating/'The' “Kama Sutra”", Third World Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3, Connecting Cultures (2005), 509–516

- ^ Pagan Press (1982–2012). "Sir Richard Francis Burton Explorer of the Sotadic Zone". Pagan Press. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ The Romance of Lady Isabel Burton (chapter 38) by Isabel Burton (1897) (URL accessed 12 June 2006)

- ^ McLynn, Frank (1990), Of No Country: An Anthology of the Works of Sir Richard Burton, Scribner's, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Kennedy, D. (2009). The highly civilized man: Richard Burton and the Victorian world. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674025523. OCLC 647823711.

- ^ Burton, Sir Richard (1991) Kama Sutra, Park Street Press, ISBN 0-89281-441-1, p. 14.

- ^ Godsall, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Lovell, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Rice, Edward (2001) [1990]. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: A Biography. Da Capo Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0306810282.

- ^ Brodie, Fawn M. (1967). The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton, W.W. Norton & Company Inc.: New York 1967, p. 3.

- ^ Obituary in Athenaeum No. 3287, 25 October 1890, p. 547.

- ^ Richard Burton by Ouida, article appearing in the Fortnightly Review June (1906) quoted by Lovell

- ^ a b c d Reyes, Raquel A. G. (2012). "Introduction". In Reyes, Raquel A. G.; Clarence-Smith, William G. (eds.). Sexual Diversity in Asia, c. 600–1950. Routledge contemporary Asia series. Vol. 37. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-415-60059-0.

- ^ a b c d e Markwell, Kevin (2008). "The Lure of the "Sotadic Zone"". The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 15 (2). Excerpted and reprinted with permission from Waitt, Gordon; Markwell, Kevin (2006). Gay Tourism: Culture and Context. New York City: Haworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-1602-7.

- ^ (§1., D)

- ^ The Book of the Thousand Nights and A Night. s.l.: Burton Society (Private printing). 1886.

- ^ William Harrison, Burton and Speke (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1984), ISBN 978-0-312-10873-1.

- ^ (Coronet Books, 1984), ISBN 0-340-34710-4.

- ^ 2006, translated as The Collector of Worlds [2008].

- ^ "Shorter Works by Richard Francis Burton".

Sources

[edit]- Cust, R.N. (1895). "Sir Richard Burton". Linguistic and oriental essays: written from the year 1861 to 1895. London: Trübner & Co. pp. 80–82.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1967). The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-907871-23-1.

- Burton, Isabel (1893). The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton KCMG, FRGS. Vol. 1 and 2. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Carnochan, W.B. (2006). The Sad Story of Burton, Speke, and the Nile; or, Was John Hanning Speke a Cad: Looking at the Evidence. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8047-5325-8.

- Edwardes, Allen (1963). Death Rides a Camel. New York: The Julian Press.

- Farwell, Byron (1963). Burton: A Biography of Sir Richard Francis Burton. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-012068-4.

- Godsall, Jon R (2008). The Tangled Web – A life of Sir Richard Burton. London: Matador Books. ISBN 978-1906510-428.

- Hastings, Michael (1978), Sir Richard Burton. A Biography, Hodder & Stoughton, London.

- Hitchman, Francis (1887), Richard F. Burton, K.C.M.G.: His Early, Private and Public Life with an Account of his Travels and Explorations, Two volumes; London: Sampson and Low.

- Jeal, Tim (2011). Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-300-14935-7.

- Kennedy, Dane (2005). The Highly Civilized Man: Richard Burton and the Victorian World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01862-4.

- Lovell, Mary S. (1998). A Rage to Live: A Biography of Richard & Isabel Burton. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04672-4.

- McDow, Thomas F. 'Trafficking in Persianness: Richard Burton between mimicry and similitude in the Indian Ocean and Persianate worlds'. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30.3 (2010): 491–511. ISSN 1089-201X

- McLynn, Frank (1991). From the Sierras to the Pampas: Richard Burton's Travels in the Americas, 1860–69. London: Century. ISBN 978-0-7126-3789-3.

- McLynn, Frank (1993). Burton: Snow on the Desert. London: John Murray Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7195-4818-5.

- Newman, James L. (2009), Paths without Glory: Richard Francis Burton in Africa, Potomac Books, Dulles, Virginia; ISBN 978-1-59797-287-1.

- Moorehead, Alan (1960). The White Nile. New York: Harper & Row. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-06-095639-4.

- Ondaatje, Christopher (1998). Journey to the Source of the Nile. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-200019-2.

- Ondaatje, Christopher (1996). Sindh Revisited: A Journey in the Footsteps of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-1-59048-221-6.

- Rice, Edward (1990). Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: The Secret Agent Who Made the Pilgrimage to Makkah, Discovered the Kama Sutra, and Brought the Arabian Nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Seigel, Jerrold (2016). Between Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary Lives. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4761-9.

- Sparrow-Niang, Jane (2014). Bath and the Nile Explorers: In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Burton and Speke's encounter in Bath, September 1864, and their 'Nile Duel' which never happened. Bath: Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution. ISBN 978-0-9544941-6-2

- Wisnicki, Adrian S. (2008). "Cartographical Quandaries: The Limits of Knowledge Production in Burton's and Speke's Search for the Source of the Nile". History in Africa. 35: 455–79. doi:10.1353/hia.0.0001. S2CID 162871275.

- Wisnicki, Adrian S. (2009). "Charting the Frontier: Indigenous Geography, Arab-Nyamwezi Caravans, and the East African Expedition of 1856–59". Victorian Studies 51.1 (Aut.): 103–37.

- Wright, Thomas (1906). The Life of Sir Richard Burton. Vol. 1 and 2. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-1-4264-1455-8. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

Further reading

[edit]- Millard, Candice (2022). River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile (Hardback). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385543101.

External links

[edit]- Complete Works of Richard Burton at burtoniana.org. Includes over 200 of Burton's journal and magazine pieces.

- Works by Sir Richard Francis Burton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Richard Francis Burton at the Internet Archive

- Works by Richard Francis Burton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Archival material relating to Richard Francis Burton". UK National Archives. – index to world holdings of Burton archival materials

- The Penetration of Arabia by David George Hogarth (1904) – discusses Burton in the second section, "The Successors"

- Capt Sir Richard Burton Museum (sirrichardburtonmuseum.co.uk), "located in a private residence in central St Ives, Cornwall UK"

- Sir Richard Francis Burton at Library of Congress, with 172 library catalogue records

- 1821 births

- 1890 deaths

- 19th-century English poets

- 19th-century English male writers

- 19th-century British explorers

- 19th-century linguists

- Alumni of Trinity College, Oxford

- Arabic–English translators

- British Arabists

- British atheists

- 19th-century British diplomats

- British East India Company Army officers

- British ethnographers

- British ethnologists

- British expatriates in the Ottoman Empire

- British military personnel of the Crimean War

- Burials at St Mary Magdalen Roman Catholic Church Mortlake

- English atheists

- English cartographers

- English male poets

- English orientalists

- 19th-century English translators

- English travel writers

- Explorers of Africa

- Explorers of Arabia

- Explorers of Asia

- Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society

- Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England

- Hajj accounts

- Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- People from Elstree

- Portuguese–English translators

- Translators of One Thousand and One Nights

- Historians of weapons