Richard von Kühlmann

Richard von Kühlmann | |

|---|---|

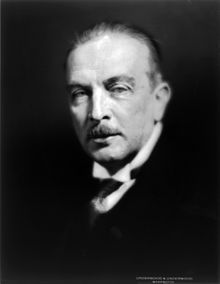

Kühlmann in 1932 | |

| State Secretary for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 6 August 1917 – 9 July 1918 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Chancellor | Georg Michaelis Georg von Hertling |

| Preceded by | Arthur Zimmermann |

| Succeeded by | Paul von Hintze |

| German Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office September 1916 – August 1917 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Preceded by | Paul Wolff Metternich |

| Succeeded by | Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff |

| German Ambassador to the Netherlands | |

| In office April 1915 – October 1916 | |

| Monarch | Wilhelm II |

| Preceded by | Felix von Müller |

| Succeeded by | Friedrich Rosen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 May 1873 Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 16 February 1948 (aged 74) Ohlstadt, Upper Bavaria, Allied-occupied Germany |

| Spouse | Baroness Margarete von Stumm |

| Children | 3 |

| Occupation | Diplomat, industrialist |

Richard von Kühlmann (3 May 1873 – 16 February 1948) was a German diplomat and industrialist. From 6 August 1917 to 9 July 1918, he served as Germany's State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and led the delegation that negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which removed the Russian Empire from World War I in March 1918.

Biography[edit]

Kühlmann was born in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). From 1908 to 1914, he was councillor of the German embassy in London, and was very active in the study of all phases of contemporary political and social life in Great Britain. He negotiated treaties on future division of African colonies and an agreement on the Bagdad Railway project with the British government which could have led to longterm improvement of German-British relationship. He therefore warned his government that the navel arms race promoted by German Admiral Tirpitz would endanger any improvement of German-British relationship. During the crisis of Juli 1914 he was on holiday in Germany and not involved in any diplomatic activities.

At the outbreak of War, Kühlmann was councillor of the embassy at Constantinople. In October 1914 he founded the News Bureau which became a vehicle for German propaganda in the Ottoman Empire. This included postcards of ruined Belgian churches, which were used to appeal to the Jihadist sentiments held by those who had participated in massacres of Christians in Constantinople in 1896[1]

During the Armenian genocide, Kühlmann was initially reluctant to expose the massacres against the Armenian population.[2] Kühlmann, who held sympathetic beliefs toward Turkish nationalism, repeatedly used the term "alleged" and excused the Turkish government for the massacres. Kühlmann, in defense of the Turkish government and the German-Turkish World War alliance, stated that the policies against the Armenians was a matter of "internal politics".[2] However, Kühlmann eventually stated that, "The destruction of the Armenians was undertaken on a massive scale. This policy of extermination will for a long time stain the name of Turkey."[2]

He was subsequently minister at The Hague, and from September 1916 until August 1917, ambassador at Constantinople.

Foreign Secretary[edit]

Appointed foreign secretary in August 1917, he led the delegation that negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which removed the Russian Empire, now under Bolshevik control, from World War I in March 1918.

In December 1917 von Kühlmann explained the main goals of his diplomacy was to subvert and undermine the political unity of the enemy states:

- The disruption of the Entente and the subsequent creation of political combinations agreeable to us constitute the most important war aim of our diplomacy. Russia appeared to be the weakest link in the enemy chain. The task therefore was gradually to loosen it, and, when possible, to remove it. This was the purpose of the subversive activity we caused to be carried out in Russia behind the front--in the first place promotion of separatist tendencies and support of the Bolsheviks. It was not until the Bolsheviks had received from us a steady flow of funds through various channels and under different labels that they were in a position to be able to build up their main organ, Pravda, to conduct energetic propaganda and appreciably to extend the originally narrow basis of their party.

- The Bolsheviks have now come to power; how long they will retain power cannot be yet foreseen. They need peace in order to strengthen their own position; on the other hand it is entirely in our interest that we should exploit the period while they are in power, which may be a short one, in order to attain firstly an armistice and then, if possible, peace.[3]

He also negotiated the Peace of Bucharest of 7 May 1918, with Romania. In the treaty negotiations, Kühlmann encountered opposition from the higher command of the army, and, in particular, of Erich Ludendorff, who desired fuller territorial guarantees on Germany's eastern frontier, the establishment of a German protectorate over the Baltic States and stronger precautions against the spread of Bolshevism.

In June 1918, he delivered in the Reichstag a speech on the general situation, in the course of which he declared that the war could not be ended by arms alone, implying that it would require diplomacy to secure peace. This utterance was misinterpreted in Germany, the High Command was drawn into the controversy which arose over it, and Kühlmann's position became untenable. He was essentially dismissed from office by the Chancellor, Georg von Hertling, in a speech notionally intended to explain away his statement and, after an interview with Emperor Wilhelm II at the front, he tendered his resignation in July 1918.

Personal life[edit]

On 25 January 1906 he married Margarete Freiin von Stumm (1884–1917), eldest daughter of Baron Hugo Rudolf von Stumm. His son was German politician and industrialist Knut von Kühlmann-Stumm (1916–1977).[4]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ McMahon, Henry (1915). The War: German attempts to fan Islamic feeling. London: British Library.

- ^ a b c W. Charney, Israel (1994). The Widening Circle of Genocide. Transaction Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 1412839653.

- ^ Z. A. B. Zeman. Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (1958) p 193

- ^ Frankfurter Rundschau: Marodes Märchenschloss-Bewegte Familiengeschichte (German)

References[edit]

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

External links[edit]

Media related to Richard von Kühlmann at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Richard von Kühlmann at Wikimedia Commons- Newspaper clippings about Richard von Kühlmann in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1873 births

- 1948 deaths

- Stumm family

- German Empire politicians

- German people of World War I

- Government ministers of Germany

- Diplomats from Istanbul

- Deutsche Schule Istanbul alumni

- Ambassadors of Germany to the Ottoman Empire

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiators

- Witnesses of the Armenian genocide

- Expatriates from the German Empire

- Expatriates in the Ottoman Empire