Ridley Scott

Ridley Scott | |

|---|---|

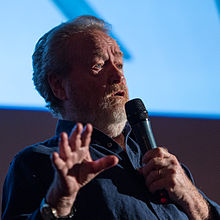

Scott in 2015 | |

| Born | 30 November 1937 South Shields, Tyne and Wear, England |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1963–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | |

| Relatives | Tony Scott (brother) |

| Awards | Full list |

Sir Ridley Scott (born 30 November 1937) is an English film director and producer. He directs films in the science fiction, crime, and historical drama genres, with an atmospheric and highly concentrated visual style.[1][2][3] He ranks among the highest-grossing directors and has received many accolades, including the BAFTA Fellowship for Lifetime Achievement in 2018, two Primetime Emmy Awards, and a Golden Globe Award.[4] He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2003,[5] and appointed a Knight Grand Cross by King Charles III in 2024.[6]

An alumnus of the Royal College of Art in London, Scott began his career in television as a designer and director before moving into advertising as a director of commercials. He made his film directorial debut with The Duellists (1977) and gained wider recognition with his next film, Alien (1979). Though his films range widely in setting and period, they showcase memorable imagery of urban environments, spanning 2nd-century Rome in Gladiator (2000) and its 2024 sequel (Gladiator II), 12th-century Jerusalem in Kingdom of Heaven (2005), medieval England in Robin Hood (2010), ancient Memphis in Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), contemporary Mogadishu in Black Hawk Down (2001), the futuristic cityscapes of Blade Runner (1982) and different planets in Alien, Prometheus (2012), The Martian (2015) and Alien: Covenant (2017).

Scott has been nominated for three Academy Awards for Directing for Thelma & Louise, Gladiator and Black Hawk Down.[2] Gladiator won the Academy Award for Best Picture, and he received a nomination in the same category for The Martian. In 1995, both Scott and his brother Tony received a British Academy Film Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema.[7] Scott's films Alien, Blade Runner and Thelma & Louise were each selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being considered "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". In a 2004 BBC poll, Scott was ranked 10 on the list of most influential people in British culture.[8] Scott also works in television, and has earned 10 Primetime Emmy Award nominations. He won twice, for Outstanding Television Film for the HBO film The Gathering Storm (2002) and for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Special for the History Channel's Gettysburg (2011).[9] He was Emmy-nominated for RKO 281 (1999), The Andromeda Strain (2008), and The Pillars of the Earth (2010).[10]

Early life and education

[edit]My mum brought three boys up: my dad was in the army and so he was frequently away. During the war and post-war, we tended to travel following him around so my mum was the boss. She laid down the law and the law was God. We just said, "Yup, okay" – we didn't argue. I think that's where the respect has come from, because she was tough.

Scott was born on 30 November 1937 in South Shields, to Francis ("Frank") Percy Scott, a partner in a commercial shipping business based in Newcastle who would serve as a Colonel in the Royal Engineers during the Second World War, and Elizabeth, née Williams, a miner's daughter.[12][13] His grand-uncle Dixon Scott was a pioneer of the cinema chain and opened many cinemas around Tyneside. One of his cinemas, Tyneside Cinema, is still operating in Newcastle and is the last remaining newsreel cinema in the UK.[14]

Born two years before the Second World War began, Scott was brought up in a military family. His father, as a senior officer in the Royal Engineers, was absent for most of his early life. His elder brother, Frank, joined the Merchant Navy when he was still young and the pair had little contact.[15] During this time the family moved around; they lived in Cumberland as well as other areas in England, in addition to Wales and Germany, where Colonel Scott was part of the post-war Allied Control Council.[12] After the war, the Scott family moved back to County Durham and eventually settled on Teesside.

His interest in science fiction began by reading the novels of H. G. Wells as a child.[16] He was also influenced by science-fiction films such as It! The Terror from Beyond Space, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Them! He said these films "kind of got [him] going a little" but his attention was not fully caught until he saw Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, about which he said, "Once I saw that, I knew what I could do."[16] He went to Grangefield Grammar School in Stockton on Tees and obtained a diploma in design at West Hartlepool College of Art.[17] The industrial landscape in West Hartlepool would later inspire visuals in Blade Runner, with Scott stating, "There were steelworks adjacent to West Hartlepool, so every day I'd be going through them, and thinking they're kind of magnificent, beautiful, winter or summer, and the darker and more ominous it got, the more interesting it got."[18]

I use everything I learned every day at art school. It's all about white sheets of paper, pens and drawing.

Scott went on to study at the Royal College of Art in London, contributing to the college magazine ARK and helping to establish the college film department. For his final show, he made a black and white short film, Boy and Bicycle, starring both his younger brother and his father (the film was later released on the "Extras" section of The Duellists DVD). In February 1963, Scott was named in the title credits as "Designer" for the BBC television programme Tonight.

After graduation in 1963, he secured a job as a trainee set designer with the BBC, leading to work on the popular television police series Z-Cars and science fiction series Out of the Unknown. He was originally assigned to design the second Doctor Who serial, The Daleks, which would have entailed realising the serial's eponymous alien creatures. Shortly before he was due to start work, a schedule conflict meant he was replaced by Raymond Cusick.[20] In 1965, he began directing episodes of television series for the BBC, only one of which, an episode of Adam Adamant Lives!, is available commercially.[21]

In 1968, Ridley and his younger brother Tony Scott – who would also go on to become a film director[22] – founded Ridley Scott Associates (RSA), a film and commercial production company.[23] Working alongside Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson and cinematographer Hugh Johnson, Ridley Scott made many commercials at RSA during the 1970s, including a 1973 Hovis bread advertisement, "Bike Round" (underscored by the slow movement of Dvořák's "New World" symphony rearranged for brass), filmed in Gold Hill, Shaftesbury, Dorset.[1][24] A nostalgia themed television advert that captured the public imagination, it was voted the UK's favourite commercial in a 2006 poll.[25][26] In the 1970s the Chanel No. 5 brand needed revitalisation having run the risk of being labelled as mass market and passé.[27] Directed by Scott in the 1970s and 1980s, Chanel television commercials were inventive mini-films with production values of surreal fantasy and seduction, which "played on the same visual imagery, with the same silhouette of the bottle."[27]

Five members of the Scott family are directors, and all have worked for RSA.[28] His brother Tony was a successful film director whose career spanned more than two decades; his sons Jake and Luke are both acclaimed directors of commercials, as is his daughter, Jordan Scott. Jake and Jordan both work from Los Angeles; Luke is based in London. In 1995, Shepperton Studios was purchased by a consortium headed by Ridley and Tony Scott, which extensively renovated the studios while also expanding and improving its grounds.[29]

Career

[edit]1970s: The Duellists, Alien

[edit]The Duellists (1977) marked Ridley Scott's first feature film as director. Shot in continental Europe, it was nominated for the main prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and won an award for Best Debut Film. The Duellists had limited commercial impact internationally. Based on Joseph Conrad's short story "The Duel" and set during the Napoleonic Wars, it follows two French Hussar officers, D'Hubert and Feraud (Keith Carradine and Harvey Keitel) whose quarrel over an initially minor incident turns into a bitter extended feud spanning fifteen years, interwoven with the larger conflict that provides its backdrop. The film has been acclaimed for providing a historically authentic portrayal of Napoleonic uniforms and military conduct.[30][31] The 2013 release of the film on Blu-ray coincided with the publication of an essay on the film in a collection of scholarly essays on Scott.[32]

Scott had originally planned next to adapt a version of Tristan and Iseult, but after seeing Star Wars, he became convinced of the potential of large scale, effects-driven films. He accepted the job of directing Alien, the 1979 horror/science-fiction film that would win him international success. Scott made the decision to switch Ellen Ripley from the standard male action hero to a heroine.[33] Ripley (played by Sigourney Weaver), who appeared in the first four Alien films, would become a cinematic icon.[33] The final scene of John Hurt's character has been named by a number of publications as one of the most memorable in cinematic history.[34] Filmed at Shepperton Studios in England, Alien was the sixth highest-grossing film of 1979, earning over $104 million worldwide.[35] Scott was involved in the 2003 restoration and re-release of the original film. In promotional interviews at the time, Scott indicated he had been in discussions to make a fifth film in the Alien franchise. However, in a 2006 interview, Scott remarked that he had been unhappy about Alien: The Director's Cut, feeling that the original was "pretty flawless" and that the additions were merely a marketing tool.[36] Scott later returned to Alien-related projects when he directed Prometheus and Alien: Covenant three decades after the original film's release.[37]

1980s: Blade Runner and other films

[edit]Outside Star Wars, no sci-fi universe has been etched into cinematic consciousness more thoroughly than Blade Runner. Ridley Scott's definitive 1982 neo-noir offered an immersive dystopia of rain-soaked windows and shadowy buildings adorned with animated neon billboards, where flying cars hum through the endless night.

After a year working on the film adaptation of Dune, and following the sudden death of his brother Frank, Scott signed to direct the film version of Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Re-titled Blade Runner and starring Harrison Ford, the film was a commercial disappointment in cinemas in 1982, but is now regarded as a classic.[39][40] In 1991, Scott's notes were used by Warner Bros. to create a rushed director's cut which removed the main character's voiceover and made a number of other small changes, including to the ending. Later Scott personally supervised a digital restoration of Blade Runner and approved what was called The Final Cut. This version was released in Los Angeles, New York City and Toronto cinemas on 5 October 2007, and as an elaborate DVD release in December 2007.[41]

Today, Blade Runner is ranked by many critics as one of the most important and influential science fiction films ever made,[42] partly thanks to its much imitated portraits of a future cityscape.[43] It is often discussed along with William Gibson's novel Neuromancer as initiating the cyberpunk genre. Stephen Minger, stem cell biologist at King's College London, states, "It was so far ahead of its time and the whole premise of the story – what is it to be human and who are we, where we come from? It's the age-old questions."[44] Scott has described Blade Runner as his "most complete and personal film".[45]

In 1985, Scott directed Legend, a fantasy film produced by Arnon Milchan. Scott decided to create a "once upon a time" tale set in a world of princesses, unicorns and goblins, filming almost entirely inside the studio. Scott cast Tom Cruise as the film's hero, Jack; Mia Sara as Princess Lili; and Tim Curry as the Satan-horned Lord of Darkness.[46] Scott had a forest set built on the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, with trees 60 feet high and trunks 30 feet in diameter.[47] In the final stages of filming, the forest set was destroyed by fire; Jerry Goldsmith's original score was used for European release, but replaced in North America with a score by Tangerine Dream. Rob Bottin provided the film's Academy Award-nominated make-up effects, most notably Curry's red-coloured Satan figure. Despite a major commercial failure on release, the film has gone on to become a cult classic. The 2002 Director's Cut restored Goldsmith's original score.[48]

Scott made Someone to Watch Over Me, a romantic thriller starring Tom Berenger and Mimi Rogers in 1987, and Black Rain (1989), a police drama starring Michael Douglas and Andy García, shot partially in Japan. The latter was very well received at the box office. Black Rain was the first of Scott's six collaborations with the composer Hans Zimmer.[49][50]

1984 Apple Macintosh commercial

[edit]In 1984, Scott directed a big-budget ($900,000) television commercial, "1984", to launch Apple Computer's Macintosh computer.[51] Scott filmed the advertisement in England for about $370,000;[52] which was given a showcase airing in the US on 22 January 1984, during Super Bowl XVIII, alongside screenings in cinemas.[53] Some consider this advertisement a "watershed event" in advertising[54] and a "masterpiece".[55] Advertising Age placed it top of its list of the 50 greatest commercials.[56]

Set in a dystopian future modelled after George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, Scott's advertisement used its hero (portrayed by English athlete Anya Major) to represent the coming of the Macintosh (indicated by her white tank top adorned with a picture of the Apple Macintosh computer) as a means of saving humanity from "conformity" (Big Brother), an allusion to IBM, at that time the dominant force in computing.[57]

1990s

[edit]The road film Thelma & Louise (1991) starring Geena Davis as Thelma, Susan Sarandon as Louise, in addition to the breakthrough role for Brad Pitt as J.D, proved to be one of Scott's biggest critical successes, helping revive the director's reputation and receiving his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Director.[58][59] His next project, independently funded historical epic 1492: Conquest of Paradise, was a box office failure. The film recounts the expeditions to the Americas by Christopher Columbus (French star Gérard Depardieu). Scott did not release another film for four years.

In 1995, Ridley and his brother Tony formed a production company, Scott Free Productions, in Los Angeles. All Ridley's subsequent feature films, starting with White Squall (starring Jeff Bridges) and G.I. Jane (starring Demi Moore), have been produced under the Scott Free banner. In 1995 the two brothers purchased a controlling interest in the British film studio Shepperton Studios. In 2001, Shepperton merged with Pinewood Studios to become The Pinewood Studios Group, which is headquartered in Buckinghamshire, England.[60]

2000s

[edit]Scott's historical drama Gladiator (2000) proved to be one of his biggest critical and commercial successes. It won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor for the film's star Russell Crowe, and saw Scott nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director.[2] Scott worked with British visual effects company The Mill for the film's computer-generated imagery, and the film was dedicated to Oliver Reed who died during filming – The Mill created a digital body double for Reed's remaining scenes.[61][62] Some have credited Gladiator with reviving the nearly defunct "sword and sandal" historical genre. The film was named the fifth best action film of all time in the ABC special Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time.[63]

Scott directed Hannibal (2001) starring Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter. The film was commercially successful despite receiving mixed reviews. Scott's next film, Black Hawk Down (2001), featuring Tom Hardy in his film debut, was based on a group of stranded US soldiers fighting for their lives in Somalia; Scott was nominated for an Oscar for Best Director.[2] In 2003, Scott directed a smaller scale project, Matchstick Men, adapted from the novel by Eric Garcia and starring Nicolas Cage, Sam Rockwell and Alison Lohman. It received mostly positive reviews but performed moderately at the box office.

In 2005, he made the modestly successful Kingdom of Heaven, a film about the Crusades. The film starred Orlando Bloom, and marked Scott's first collaboration with the composer Harry Gregson-Williams.[64] The Moroccan government sent the Moroccan cavalry as extras for some battle scenes.[65] Unhappy with the theatrical version of Kingdom of Heaven (which he blamed on paying too much attention to the opinions of preview audiences in addition to relenting when Fox wanted 45 minutes shaved off), Scott supervised a director's cut of the film, the true version of what he wanted, which was released on DVD in 2006.[66] The director's cut of Kingdom of Heaven has been met with critical acclaim, with Empire magazine calling the film an "epic", adding: "The added 45 minutes in the director's cut are like pieces missing from a beautiful but incomplete puzzle."[67] "This is the one that should have gone out" reflected Scott.[67] Asked if he was against previewing in general in 2006, Scott stated: "It depends who's in the driving seat. If you've got a lunatic doing my job, then you need to preview. But a good director should be experienced enough to judge what he thinks is the correct version to go out into the cinema."[68]

Scott teamed up again with Gladiator star Russell Crowe for A Good Year, based on the best-selling book by Peter Mayle about an investment banker who finds a new life in Provence. The film was released on 10 November 2006. A few days later Rupert Murdoch, chairman of studio 20th Century Fox (who backed the film) dismissed A Good Year as "a flop" at a shareholders' meeting.[69]

Scott's next film was American Gangster, based on the story of real-life drug kingpin Frank Lucas. Scott took over the project in early 2006 and had screenwriter Steven Zaillian rewrite his script to focus on the dynamic between Frank Lucas and Richie Roberts. Denzel Washington signed on to the project as Lucas, with Russell Crowe co-starring as Roberts. The film premiered in November 2007 to positive reviews and box office success, and Scott was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Director.[2]

In late 2008, Scott's espionage thriller Body of Lies, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe, opened to lukewarm ticket-sales and mixed reviews. Scott directed a revisionist adaptation of Robin Hood, which starred Russell Crowe as Robin Hood and Cate Blanchett as Maid Marian. It was released in May 2010 to mixed reviews, but a respectable box-office.

On 31 July 2009, news surfaced of a two-part prequel to Alien with Scott attached to direct.[37][70] The project, ultimately reduced to a single film called Prometheus, which Scott described as sharing "strands of Alien's DNA" while not being a direct prequel, was released in June 2012. The film starred Charlize Theron and Michael Fassbender, with Noomi Rapace playing the leading role of the scientist named Elizabeth Shaw. The film received mostly positive reviews and grossed $403 million at the box office.[71][72]

In August 2009, Scott planned to direct an adaptation of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World set in a dystopian London with Leonardo DiCaprio.[73] In 2009, the TV series The Good Wife premiered with Ridley and his brother Tony credited as executive producers.

2010s

[edit]On 6 July 2010, YouTube announced the launch of Life in a Day, an experimental documentary executive produced by Scott. Released at the Sundance Film Festival on 27 January 2011, it incorporates footage shot on 24 July 2010 submitted by YouTube users from around the world.[74] As part of the buildup to the 2012 London Olympics, Scott produced Britain in a Day, a documentary film consisting of footage shot by the British public on 12 November 2011.[75]

In 2012, Scott produced the commercial for Lady Gaga's fragrance, "Fame". It was touted as the first ever black Eau de Parfum, in the informal credits attached to the trailer for this advertisement. On 24 June 2013, Scott's series Crimes of the Century debuted on CNN.[76] In November 2012 it was announced that Scott would produce the documentary, Springsteen & I directed by Baillie Walsh and inspired by Life in a Day, which Scott also produced. The film featured fan footage from throughout the world on what musician Bruce Springsteen meant to them and how he impacted their lives.[77] The film was released for one day only in 50 countries and on over 2000 film screens on 22 July 2013.[77]

Scott directed The Counselor (2013), with a screenplay by author Cormac McCarthy.[78][79] On 25 October 2013, Indiewire reported that "Before McCarthy sold his first spec script for Scott's (The Counselor) film, the director was heavily involved in developing an adaptation of the author's 1985 novel Blood Meridian with screenwriter Bill Monahan (The Departed). But as Scott said in a Time Out interview, '[Studios] didn't want to make it. The book is so uncompromising, which is what's great about it.' Described as an 'anti-western'..."[80] Scott directed the biblically inspired epic film Exodus: Gods and Kings, released in December 2014 which received negative reviews from critics (particularly for the casting of white actors as Middle Eastern characters) and grossed $268 million worldwide on a $140 million budget, making it a financial disappointment. Filmed at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, the film starred Christian Bale in the lead role.[81]

In May 2014, Scott began negotiations to direct The Martian, starring Matt Damon as Mark Watney.[82] Like many of Scott's previous works, The Martian features a heroine in the form of Jessica Chastain's character who is the mission commander.[83] The film was originally scheduled for release on 25 November 2015, but Fox later switched its release date with that of Victor Frankenstein, and thus The Martian was released on 2 October 2015.[84][85] The Martian was a critical and commercial success, grossed over $630 million worldwide, becoming Scott's highest-grossing film to date.[86][87][88]

A sequel to Prometheus, Alien: Covenant, started filming in 2016, premiered in London on 4 May 2017, and received general release on 19 May 2017.[89] The film received generally positive reviews from critics, with many praising Michael Fassbender's dual performance and calling the film a return to form for both director Ridley Scott and the franchise.[90][91]

In August 2011, information leaked about production of a sequel to Blade Runner by Alcon Entertainment, with Alcon partners Broderick Johnson and Andrew Kosove.[92] Scott informed the Variety publication in November 2014 that he was no longer the director for the film and would only fulfill a producer's role. Scott also revealed that filming would begin sometime within 2015, and that Harrison Ford has signed on to reprise his role from the original film but his character should only appear in "the third act" of the sequel.[93] On 26 February 2015, the sequel was officially confirmed, with Denis Villeneuve hired to direct the film, and Scott being an executive producer.[94] The sequel, Blade Runner 2049, was released on 6 October 2017 to universal acclaim.[95]

From May to August 2017, Scott filmed All the Money in the World, a drama about the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III, starring Mark Wahlberg and Michelle Williams.[96][97] Kevin Spacey originally portrayed Getty Sr. However, after multiple sexual assault allegations against the actor, Scott decided to replace him with Christopher Plummer, saying "You can't condone that kind of behaviour in any shape or form. We cannot let one person's action affect the good work of all these other people. It's that simple."[98] Scott began re-shooting Spacey's scenes with Plummer on 20 November, which included filming at Elveden Hall in west Suffolk, England.[98] With a release date of 25 December 2017, the film studio had its doubts that Scott would manage it, saying: "They were like, 'You'll never do it. God be with you.'"[98][99]

2020s

[edit]In 2020, Scott directed The Last Duel, a film adaptation of Eric Jager's 2004 book The Last Duel: A True Story of Crime, Scandal, and Trial by Combat in Medieval France, starring Adam Driver, Matt Damon and Jodie Comer which was released on 15 October 2021[100] to positive reviews but it bombed at the box office, grossing only $30.6 million against a production budget of $100 million.[101] Filming locations included the French medieval castle of Berzé-le-Châtel (with a film crew of 300 people including 100 extras),[102] and Ireland.[103]

In 2021, he directed House of Gucci, a film about the murder of Maurizio Gucci orchestrated by Patrizia Reggiani, who were portrayed by Adam Driver and Lady Gaga, respectively. Scott had originally been set to direct the film in 2006, but the project languished in development hell for several years, with different directors entering talks to sign on, before he returned to the project in November 2019.[104][105] The film was released on 24 November 2021.[106]

Scott next directed Napoleon, a biopic of Napoleon Bonaparte starring Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon and Vanessa Kirby as Empress Joséphine, the first wife of Napoleon.[107] Filming began in February 2022; the film was released on 22 November 2023 by Sony Pictures Releasing before streaming on Apple TV+ on 1 March 2024.[108]

Scott's next film was Gladiator II, a sequel to Gladiator, starring Paul Mescal, Denzel Washington, and Pedro Pascal.[109][110] The film, which began production in June 2023 but had been discussed since early 2001, was released on 22 November 2024.[111][112]

Upcoming projects

[edit]In February 2024, it was reported that Scott was in negotiations to direct Paramount Pictures' untitled Bee Gees biopic, written by John Logan and Joe Penhall. The film is scheduled to begin principal photography in September 2025 in London and Miami.[113][114][115][116] In November that year, Scott's next project was confirmed to be an adaptation of The Dog Stars, with principal photography set to begin on 1 April 2025, in Italy.[117][118]

While promoting Gladiator II, in a September 2024 interview for French network La Premiere, Scott revealed that he was planning a Gladiator III, comparing the ending of II to The Godfather; "with Michael Corleone ending up with a job he didn't want [...] So the next [film] will be about a man who doesn't want to be where he is."[114]

Television projects

[edit]In 2002, Ridley Scott and his brother Tony were among the executive producers of The Gathering Storm, a television biographical film of Winston Churchill in the years just prior to World War II. A BBC–HBO co-production, it received acclaim, with Mark Lawson of The Guardian ranking it as the most memorable television portrayal of Churchill.[119] The brothers produced the CBS series Numb3rs (2005–10), a crime drama about a genius mathematician who helps the FBI solve crimes; and The Good Wife (2009–2016), a legal drama about an attorney balancing her job with her husband, a former state attorney trying to rebuild his political career after a major scandal. The two Scotts also produced a 2010 film adaptation of 1980s television show The A-Team, directed by Joe Carnahan.[120][121]

Ridley Scott was an executive producer of the first season of Amazon's The Man in the High Castle (2015–16).[122] Through Scott Free Productions, he is an executive producer on the dark comic science-fiction series BrainDead which debuted on CBS in 2016.[123][124][125]

On 20 November 2017, Amazon agreed a deal with AMC Studios for a worldwide release of The Terror, Scott's series adaptation of Dan Simmons' novel, a speculative retelling of British explorer Sir John Franklin's lost expedition of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to the Arctic in 1845–1848 to force the Northwest Passage, with elements of horror and supernatural fiction, and the series premiered in March 2018.[126][127] Scott was an executive producer for the 2019 BBC/FX three-part miniseries A Christmas Carol, developed by Steven Knight, alongside Tom Hardy.[128]

Scott's first television directing role in 50 years, Raised by Wolves, was released on HBO Max in 2020.[129][130] Scott said his "tendency was to think, 'I don't want to go down that road of androids again'", but decided to take on the project after he read the script and liked it.[130] The show revolves around androids Mother and Father, who attempt to save humankind on planet Kepler-22b after earth is demolished by war between the Mithraic, who follow a god called Sol, and militant atheists.[131]

In August 2022, it was announced Scott would executive produce the Apple TV+ series Dope Thief, written by Peter Craig and starring Brian Tyree Henry, and would also direct an episode.[132]

Personal life

[edit]

Ridley Scott was married to Felicity Heywood from 1964 to 1975. The couple had two sons, Jake and Luke,[133] both of whom work as directors in Scott's production company, Ridley Scott Associates. Scott later married advertising executive Sandy Watson in 1979, with whom he had a daughter, Jordan Scott, also a director, and divorced in 1989.[134] In 2015 he married actress Giannina Facio,[135] whom he has cast in all his films since White Squall except American Gangster and The Martian.[136] He divides his time between homes in London, France, and Los Angeles.[81]

His eldest brother Frank died, aged 45, of skin cancer in 1980.[137] His younger brother Tony, who was also his business partner in their company Scott Free, died on 19 August 2012 at the age of 68 after jumping from the Vincent Thomas Bridge which spans Los Angeles Harbor, after an originally disputed long struggle with cancer.[138] Before Tony's death, he and Ridley collaborated on a miniseries based on Robin Cook's novel Coma for A&E. The two-part miniseries premiered on A&E on 3 September 2012, to mixed reviews.[139]

Scott has dedicated several of his films in memory of his family: Blade Runner to his brother Frank, Black Hawk Down to his mother, and The Counselor and Exodus: Gods and Kings to his brother Tony.[140] Ridley also paid tribute to his late brother Tony at the 2016 Golden Globes, after his film, The Martian, won Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[141]

In 2013, Scott stated that he is an atheist.[142] Although when asked by the BBC in a September 2014 interview if he believes in God, Scott replied:

I'm not sure. I think there's all kinds of questions raised... that's such an exotic question. If we looked at the whole thing practically speaking, the Big Bang occurred and then we go through this evolution of millions, billions of years where, by coincidence, all the right biological accidents came out the right way. To an extent, that doesn't make sense unless there was a controlling decider or mediator in all of that. So who was that? Or what was that? Are we one big grand experiment in the basic overall blink of the universe, or the galaxy? In which case, who is behind it?[143]

Directorial style

[edit]Scott's frequent collaborator Russell Crowe commented, "I like being on Ridley's set because actors can perform [...] and the focus is on the performers."[144] Paul M. Sammon, in his book Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, commented in an interview with Brmovie.com that Scott's relationship with his actors has improved considerably over the years.[145] More recently during the filming of Scott's 2012 film, Prometheus, Charlize Theron praised the director's willingness to listen to suggestions from the cast for improvements in the way their characters are portrayed on screen. Theron worked alongside the writers and Scott to give more depth to her character during filming.[146] When working on epics, Scott states, "there's always the danger that the characters can get swamped" on a large canvas, before adding, "My model is David Lean, whose characters never got lost in the proscenium."[147]

Scott's work is identified for its striking visuals, with heroines also a common theme.[2][11][148][149] Los Angeles Times film editor Joshua Rothkopf wrote "Scott may be the movies' most consistent stealth feminist".[107] His visual style, incorporating a detailed approach to production design and innovative, atmospheric lighting, has been influential on a subsequent generation of filmmakers.[2][3] James Cameron commented, "I love Ridley's films and I love his filmmaking, I love the beauty of the photography, I love the visceral sense that you're there, that you're present."[150] Scott commonly uses slow pacing until the action sequences. Examples include Alien and Blade Runner; the Los Angeles Times critic Sheila Benson, for example, would call the latter "Blade Crawler" "because it's so damn slow". Scott claims to have an eidetic memory, which he says aids him in visualising and storyboarding the scenes in his films.[151]

Scott has developed a method for filming intricate shots as swiftly as possible: "I like working, always, with a minimum of three cameras. [...] So those 50 set-ups [a day] might only be 25 set-ups except I'm covering in the set-up. So you're finished. I mean, if you take a little bit more time to prep on three cameras, or if it's a big stunt, eleven cameras, and – whilst it may take 45 minutes to set up – then when you're ready you say 'Action!', and you do three takes, two takes and is everybody happy? You say, 'Yeah, that's it.' So you move on."[144]

Artificial intelligence is a theme that appears in several of Scott's films, including Blade Runner, Alien, and Prometheus.[152] The 2013 book The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott identifies pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing and the philosopher John Searle as presenting relevant models of testing artificial intelligence known as the Turing test and the Chinese Room Thought Experiment, respectively, in the chapter titled "What's Wrong with Building Replicants", which has been a recurring theme for many of Scott's films.[153] The chapter titled "Artificial Intelligence in Blade Runner, Alien, and Prometheus," concludes by citing the writings of John Stuart Mill in the context of Scott's Nexus-6 Replicants in Blade Runner (Rutger Hauer), the android Ash (Ian Holm) in Alien, and the android David 8 (Michael Fassbender) in Prometheus, where Mill is applied to assert that measures and tests of intelligence must also assess actions and moral behaviour in androids to effectively address the themes which Scott explores in these films.[154]

DVD format and director's cut

[edit]

Scott provides audio commentaries and interviews for all his films where possible. In the July 2006 issue of Total Film magazine, he stated: "After all the work we go through, to have it run in the cinema and then disappear forever is a great pity. To give the film added life is really cool for both those who missed it and those who really loved it."[68]

The positive reaction to the Blade Runner Director's Cut encouraged Scott to re-cut several movies that were a disappointment at the time of their release (including Legend and Kingdom of Heaven), which have been met with acclaim.[67] Today the practice of alternative cuts is more commonplace, though often as a way to make a film stand out in the DVD marketplace by adding new material.

Filmography

[edit]Honours and awards

[edit]

Scott was knighted in the 2003 New Year Honours for services to the British film industry.[155] He received his accolade from Queen Elizabeth II at an investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 8 July 2003.[5] Scott admitted feeling "stunned and truly humbled" after the ceremony, saying, "As a boy growing up in South Shields, I could never have imagined that I would receive such a special recognition. I am truly humbled to receive this treasured award and believe it also further recognises the excellence of the British film industry."[156] He was appointed a Knight Grand Cross by King Charles III in 2024.[157]

He has been nominated for three Academy Awards for Directing—Thelma & Louise, Gladiator and Black Hawk Down—as well as three British Academy Film Awards for Best Director, four Golden Globe Awards for Best Director, and two Primetime Emmy Awards. In 1995, Ridley and his brother Tony received the BAFTA for Outstanding British Contribution To Cinema.[7] In 2018 he received the highest accolade from BAFTA, the BAFTA Fellowship, for lifetime achievement.[4][7]

Scott was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2007.[158] In 2017 the German newspaper FAZ compared Scott's influence on the science fiction film genre to Sir Alfred Hitchcock's on thrillers and John Ford's on Westerns.[159] In 2011, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[160]

Scott has received three Hugo Awards in the category of Best Dramatic Presentation for Alien, Blade Runner and The Martian.[161][162] In 2012, Scott was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork, the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admires to mark his 80th birthday.[163] On 3 July 2015, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Royal College of Art in a ceremony at the Royal Albert Hall in London at which he described how he still keeps on his office wall his school report placing him 31st out of 31 in his class, and how his teacher encouraged him to pursue what became his passion at art school.[164][165]

| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1977 | The Duellists | 2 | |||||

| 1979 | Alien | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | |

| 1982 | Blade Runner | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 1985 | Legend | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 1989 | Black Rain | 2 | |||||

| 1991 | Thelma & Louise | 6 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| 1992 | 1492: Conquest of Paradise | 1 | |||||

| 2000 | Gladiator | 12 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| 2001 | Black Hawk Down | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 2007 | American Gangster | 2 | 5 | 3 | |||

| 2012 | Prometheus | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2015 | The Martian | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | ||

| 2017 | All the Money in the World | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 2021 | House of Gucci | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||

| 2023 | Napoleon | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Total | 44 | 9 | 65 | 9 | 23 | 5 | |

Directed Academy Award performances

| Year | Performer | Film | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award for Best Actor | |||||||

| 2000 | Russell Crowe | Gladiator | Won | ||||

| 2015 | Matt Damon | The Martian | Nominated | ||||

| Academy Award for Best Actress | |||||||

| 1991 | Geena Davis | Thelma and Louise | Nominated | ||||

| Susan Sarandon | Nominated | ||||||

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor | |||||||

| 2000 | Joaquin Phoenix | Gladiator | Nominated | ||||

| 2017 | Christopher Plummer | All the Money in the World | Nominated | ||||

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress | |||||||

| 2007 | Ruby Dee | American Gangster | Nominated | ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Jets, jeans and Hovis". The Guardian. 13 June 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ridley Scott". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 June 2023. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b Matthews, Jack (4 October 1992). "Regarding Ridley : For 15 years Ridley Scott has dazzled us with expressive imagery. 'Every time you make a film, really you're making a novel,' says the director". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Sir Ridley Scott gets top Bafta honour". BBC News. 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Queen knights Gladiator director". BBC News. 8 July 2003. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Gecsoyler, Sammy (29 December 2023). "New year honours 2024: awards for Shirley Bassey, Mary Earps and Michael Eavis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Outstanding British Contribution To Cinema". BAFTA. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ "iPod's low-profile creator tops cultural chart". The Independent. 18 March 2017. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Why Albert Finney Was the Perfect Winston Churchill: 'An English Bulldog of an Actor'". Variety. 9 February 2019. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Ridley Scott – Emmy Awards, Nominations, and Wins". www.emmys.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Ridley Scott: Sexism is real, take it seriously". Daily Life. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ a b Ridley Scott: A Biography, Vincent LoBrutto, University Press of Kentucky, 2019, p. 1

- ^ "How Winston helped save the nation". Scotsman.com Living. 6 July 2002. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ Hodgson, Barbara (16 February 2018). "Who is Ridley Scott? Read our guide to the North East-born star as he receives top award". Chronicle. Newcastle: chroniclelive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Ten Things About... Ridley Scott". Digital Spy. 19 December 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Ridley Scott: 'Why the hell would I want to go to Mars?". The Daily Telegraph. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Film fans can watch Sir Ridley Scott's first movie for free". Hartlepool Mail. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Monahan, Mark (20 September 2003), "Director Maximus", The Daily Telegraph, London, archived from the original on 21 June 2008, retrieved 27 July 2011

- ^ Ridley Scott – Hollywood's Best Film Directors. Sky Arts. 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2016

- ^ Howe, David J.; Mark Stammers, Stephen James Walker (1994). The Handbook: The First Doctor — The William Hartnell Years 1963–1966. Virgin Books. p. 61. ISBN 0-426-20430-1.

- ^ "Adam Adamant Lives!" Archived 18 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 19 October 2016

- ^ "Ridley Scott". Empire. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Dutta, Kunal (30 November 2007). "Great Scott – Forty years of RSA". Campaign.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Iain Sinclair (20 January 2011). "The Raging Peloton". London Review of Books. Vol. 33, no. 2. pp. 3–8. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

As proudly as the freshly baked loaves in Ridley Scott's celebrated [Hovis] commercial, shot in 1973, on the picturesque slopes of Shaftesbury.

- ^ "Ridley Scott's Hovis advert is voted all-time favourite". The independent. No. 2 May 2006. 13 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Hovis: 120 years of Goodness" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b Mazzeo, Tilar J. (2010). The Secret of Chanel No. 5. HarperCollins. pp. 197, 199.

- ^ "Ridley Scott Associates (RSA)". Rsafilms.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "History of Shepperton Studios" (PDF). pinewoodgroup.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008.

- ^ Adam Barkman, Ashley Barkman, Nancy Kang (2013). "The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott". Chapter 10. Celebrating Historical Accuracy in The Duellists. p.171-178. Lexington Books

- ^ "The Duellists: it takes two to tangle". The Guardian. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "A Double-Edged Sword: Honor in The Duellists Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine", in The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott, eds. Adam Barkman, Ashley Barkman, and Jim McRae (Lexington Books, 2013), 45–60.

- ^ a b "Great Female Roles That Were Originally Written for Men". Vanity Fair. 17 December 2016. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Sources that refer to the final scene of Hurt's character in Alien as one of the most memorable in cinematic history include these:

- BBC News (26 April 2007). "Alien named as top 18-rated scene". British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravo. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- "The making of Alien's chestburster scene". The Guardian. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Alien". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "A good year ahead for Ridley". BBC News. 20 October 2006. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (27 April 2010). "Ridley Scott plans two-part Alien prequel". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Kohn, Eric (29 September 2017). "Blade Runner 2049 review – Denis Villeneuve's Neo-Noir Sequel Is Mind-Blowing Sci-Fi Storytelling". Indiewire. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Blade Runner tops scientist poll", BBC News, 26 August 2004, archived from the original on 13 May 2014, retrieved 9 January 2015

- ^ "How Ridley Scott's sci-fi classic, Blade Runner, foresaw the way we live today". The Spectator. 10 January 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Blade Runner Final Cut Due", SciFi Wire, 26 May 2006 Archived 2 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Top 10 sci-fi films". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Impeccably cool 'Blade Runner 2049' is a ravishing visual feast: EW review". Entertainment Weekly. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "'I've seen things...'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Barber, Lynn (2 January 2002). "Scott's Corner". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ "Ridley Scott's beautiful dark twisted fantasy: the making of Legend". The Daily Telegraph. 17 November 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Pirani, Adam (December 1985). "Ridley Scott: SF's Visual Magician". Starlog. p. 64.

- ^ "5 Fractured Fairy Tale Movies Worth Watching After 'Snow White and the Huntsman'". Indiewire. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Hans Zimmer career interview". Empire magazine. 21 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Orchestral manoeuvres in the dark". GQ. 21 October 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014.

- ^ Friedman, Ted (2005). "Chapter 5: 1984". Electric Dreams: Computers in American Culture. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-2740-9. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Burnham, David (4 March 1984). "The Computer, the Consumer and Privacy". The New York Times. Washington DC. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Apple's 1984: The Introduction of the Macintosh in the Cultural History of Personal Computers". Duke.edu. Archived from the original on 5 October 1999. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Apple's '1984' Super Bowl commercial still stands as watershed event". USA Today. 28 January 2004. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (3 February 2006). "Why 2006 isn't like '1984'". CNN. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (14 March 1995). "The Media Business: Advertising; A new ranking of the '50 best' television commercials ever made". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

The choice for the greatest commercial ever was the spectacular spot by Chiat/Day, evocative of the George Orwell novel 1984, that introduced the Apple Macintosh computer during Super Bowl XVIII in 1984.

- ^ Cellini, Adelia (January 2004). "The Story Behind Apple's '1984' TV commercial: Big Brother at 20". MacWorld 21.1, page 18. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Russell Smith (19 October 1993). "Brad Pitt Only Does Interesting Movie Roles". Deseret News. p. EV6.

It was in 1991, when he hitched his ride with Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon in Thelma & Louise, that Pitt's star began to twinkle in earnest.

- ^ "Brad Pitt's epic journey". BBC News. 13 May 2004. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Ridley Scott: 'I'm doing pretty good, if you think about it'". The Independent. 21 October 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Hassan, Genevieve (10 April 2017). "Missing in action: The films affected by actors' deaths". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Patterson, John (27 March 2015). "CGI Friday: a brief history of computer-generated actors". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ "Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time". ABC. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Gajewski, Ryan (3 October 2015). "'The Martian' Composer on Creating Matt Damon's Theme, Ridley Scott's 'Prometheus' Plans". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Mooviess.com Kingdom of Heaven production notes". Archived from the original on 12 November 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ "Kingdom of Heaven: Director's Cut DVD official website". Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "Directors Cuts, the Good, the Bad, and the Unnecessary". Empire. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ a b Total Film magazine, July 2006: 'Three hours, eight minutes. It's beautiful.' (Interview to promote Kingdom of Heaven: The Director's Cut)

- ^ "A Good Year is a 'flop', Murdoch admits". The Guardian. UK. 16 November 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ^ "Ridley Scott Talks 'Alien' Prequel and Timeline". Bloody-disgusting.com. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Prometheus Box Office". boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Prometheus 2 synopsis reveals Ridley Scott's Alien: Covenant will feature Michael Fassbender but not another main character". The Independent. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Brave move for DiCaprio and Scott". BBC News. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Life in a Day". The Official YouTube Blog. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "London 2012 Britain in a Day project launched" Archived 17 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 9 January 2015

- ^ "CNN's Newest Series Brings Filmmaker Ridley Scott To Sundays". Variety. 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Springsteen & I: fans tell their stories of The Boss". The Daily Telegraph. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Ridley Scott in Talks For Cormac McCarthy's 'The Counselor'". Deadline. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "First Looks at Michael Fassbender and Brad Pitt Filming 'The Counselor'". INeedMyFix.com. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Indiewire, 25 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Ridley Scott on the future of Prometheus". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Ridley Scott in Talks to Direct Matt Damon in 'The Martian' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Ridley Scott on 'The Martian,' His Groundbreaking '1984' Apple Commercial, and 'Prometheus 2'". The Daily Beast. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ Anderton, Ethan (1 August 2014). "Fox Shifts Release Dates for 'The Martian,' 'Miss Peregrine' & More". firstshowing.net. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Busch, Anita (10 June 2015). "Fox Switches 'The Martian' and 'Victor Frankenstein' Release Dates". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Ridley Scott Movie Box Office". boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Driscoll, Molly (14 September 2015). "Toronto Film Festival: 'The Martian,' 'Room' get critics talking". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Lang, Brent (29 September 2015). "Box Office: 'The Martian' to Blast Off With $45 Million". Variety. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "'Prometheus 2' Lands 'Green Lantern' Writer; May Feature Multiple Michael Fassbenders (Exclusive)". TheWrap. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Chang, Justin (17 May 2017). "Ridley Scott's 'Alien: Covenant' is a sleek, suspenseful return to form". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ ""Alien: Covenant" Film Review: Ridley Scott Returns to Form With Chest-Bursting Thrills". The Tracking Board. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Ridley Scott To Direct New 'Blade Runner' Installment For Alcon Entertainment". Deadline New York. 19 August 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (25 November 2014). "Ridley Scott won't direct 'Blade Runner' sequel". The Verge. Vox Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "'Blade Runner' sequel concept art: See a first look". Entertainment Weekly. 15 June 2016. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Busch, Anita (6 October 2016). "'Blade Runner' Sequel Finally Has A Title, Will Offer VR Experiences For Film Through Oculus – Update". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (13 March 2017). "Ridley Scott To Next Helm Getty Kidnap Drama; Natalie Portman Courted". Deadline. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (31 March 2017). "Michelle Williams, Kevin Spacey, Mark Wahlberg Circling Ridley Scott's Getty Kidnap Film". Deadline. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "Director Ridley Scott talks about replacing Kevin Spacey in new film". BBC. 1 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "All the Money in the World (2017)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (23 July 2020). "'Mulan' Off The Calendar; Disney Also Delays 'Avatar' & 'Star Wars' Movies By One Year As Studio Adjusts To Pandemic". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Recherche doublures pour Matt Damon, Adam Driver et Jodie Comer pour un tournage en Dordogne". francebleu (in French). 14 January 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "#casting doublures Matt Damon, Adam Driver et Jodie Comer pour film de Ridley Scott". Figurants. 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Caubel, Théo (13 February 2020). "Discrétion de mise à Sarlat autour du dernier Ridley Scott" (in French). Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Lang, Brent (17 October 2021). "Box Office: 'Halloween Kills' Scores Bloody Great $50.4 Million Debut, 'The Last Duel' Bombs". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "The Last Duel (2021)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "The Last Duel (2021)". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ ""The Last Duel" by Damien VALETTE (23 January 2020)". www.lejsl.com (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "Extras Casting announced for Ridley Scott Epic Period Feature 'The Last Duel'". Irish Film & Television Network. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (1 November 2019). "Lady Gaga, Ridley & Giannina Scott Team On Film About Assassination Of Gucci Grandson Maurizio; Gaga To Play Convicted Ex-Wife Patrizia Reggiani". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Gardner, Chris (21 June 2006). "Gucci bio gets going". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Kit, Borys; Siegel, Tatiana (8 April 2020). "MGM Buys Ridley Scott's 'Gucci' Film With Lady Gaga Set to Star (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ a b Rothkopf, Joshua (21 November 2023). "Vanessa Kirby commands the heart of 'Napoleon.' Her director knows about strong women". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

Kirby's Joséphine joins the sisterhood of director Ridley Scott's women, characters marked by strength and savvy, overtly in "Thelma & Louise" and "G.I. Jane," but just as palpably in scene-stealing turns from Lorraine Bracco in 1987's "Someone to Watch Over Me," Jodie Comer in "The Last Duel" and Lady Gaga in the deep-dish-of-crazy "House of Gucci." Scott may be the movies' most consistent stealth feminist

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (14 October 2020). "Ridley Scott Eyes Another Epic: Joaquin Phoenix As Napoleon In 'Kitbag' As Director Today Wraps 'The Last Duel'". Deadline. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- Goldbart, Max (22 November 2021). "Ridley Scott Hits Back At Gucci Family Criticism; Reveals Napoleon Biopic 'Kitbag' Filming Date". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Kit, Borys (4 January 2022). "Jodie Comer Exits Ridley Scott's Napoleon Drama 'Kitbag' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (18 January 2022). "Kevin Walsh Moves From Scott Free Prexy To Multi-Year Apple TV+ Producing Deal". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (19 January 2022). "Michael Pruss Elevated To President Of Ridley Scott's Scott Free Films". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- Lang, Brent (3 April 2023). "Ridley Scott, Joaquin Phoenix Epic 'Napoleon' Gets Exclusive Theatrical Release Before Apple TV+ Debut". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- Pedersen, Erik (15 February 2024). "'Napoleon' Streaming Campaign Gets Start Date On Apple TV+". Deadline. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- "Napoleon". Apple TV+ Press. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (6 January 2023). "Paul Mescal To Star In Ridley Scott's 'Gladiator' Sequel For Paramount". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (1 May 2023). "Pedro Pascal Joins Ridley Scott's 'Gladiator' Sequel At Paramount". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Rajput, Priyanca (8 June 2023). "Ridley Scott's Gladiator 2 enters production". KFTV.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (9 June 2023). "'Gladiator 2' Accident Injures Multiple Crewmembers". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (16 February 2024). "Ridley Scott To Direct Paramount's Bee Gees Movie From GK Films". Deadline. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ a b Hibberd, James; Couch, Aaron (20 September 2024). "Ridley Scott Planning a 'Gladiator 3': 'There's Already an Idea'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Justin; Mike Fleming Jr (8 November 2024). "Ridley Scott Back In Arena With 'Gladiator II' Star Paul Mescal On 'The Dog Stars' At 20th Century". Deadline. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Sir Ridley Scott on Gladiator II". Apple Podcasts. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Stephan, Katcy (8 November 2024). "Ridley Scott and Paul Mescal to Re-Team After 'Gladiator II' on 'The Dog Stars'". Variety. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr (13 November 2024). "Ridley Scott On Why 'Gladiator II' Is His Most Ambitious Film: Will It Finally Win Him The Oscar? – The Deadline Q&A". Deadline. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (26 February 2016). "Close but no cigar: TV's Winston Churchills – ranked". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Ridley Scott to remake The A-Team". BBC News Online. 28 January 2009. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (27 January 2009). "Fox assembles 'A-Team'". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Watch The Man in the High Castle Season 1 Episode – Amazon Video". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "BrainDead". Backstage. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "Ridley Scott". Hollywood.com. 26 November 2014. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Lloyd, Robert (13 June 2016). "'The Good Wife's' creators are back with the imperfect but fun 'Braindead' mixing D.C politics ... and bugs from space". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (2 March 2016). "AMC Orders 'The Terror' Anthology Drama Series From Scott Free". Deadline. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (13 February 2013). "AMC Developing 'Terror' Drama Produced By Scott Free, TV 360 & Alexandra Milchan". Deadline. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (28 November 2017). "Steven Knight To Adapt Charles Dickens Novels For BBC One; Ridley Scott, Tom Hardy Exec Producing". Deadline. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Ridley Scott's Raised by Wolves Coming to HBO Max" (Press release). 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Vineyard, Jennifer (1 October 2020). "'Raised by Wolves': Ridley Scott Explains That Monstrous Finale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Kiesling, Lydia (5 October 2020). "The Aspirational Android Parenting of "Raised by Wolves"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ White, Peter (11 August 2022). "Brian Tyree Henry To Star In Philadelphia Crime Series Sinking Spring For Apple From Top Gun: Maverick Writer Peter Craig & Ridley Scott". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "A Reel Life: Jordan Scott" Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (19 November 2009). Evening Standard. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Ridley Scott: Interviews". p. xviii. University Press of Mississippi, 2005

- ^ Mottram, James (3 September 2010). "Ridley Scott: 'I'm doing pretty good, if you think about it'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Sir Ridley Scott: Hollywood visionary" Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Harper, Tom; Jury, Louise (20 August 2012). "Hollywood pays tribute to Top Gun director Tony Scott following suicide leap". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Ridley Scott breaks silence on brother Tony Scott's death". The Daily Telegraph. 28 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Coma – Reviews, Ratings, Credits and More". Metacritic. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott's Spirit Possesses Ridley Scott's The Counselor". Roger Ebert. 4 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2016 ceremony – in pictures". The Guardian. 30 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (25 October 2013). "Ridley Scott: 'Most Novelists Are Desperate to Do What I Do'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Carnevale, Rob (24 September 2014). "Calling the Shots No.41: Ridley Scott". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ a b American Gangster DVD, Fallen Empire: The Making of American Gangster documentary

- ^ Caldwell, David. "Paul M. Sammon interview". BRmovie.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ ""Prometheus" Crew: On A Mission Collision". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 29 April 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (28 May 2012). "Ridley Scott's Brilliant First Film". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Ridley Scott's History of Directing Strong Women". Newsweek. 17 December 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Yahoo! Movies: Ridley Scott". Yahoo!. 30 November 1937. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Wax, Alyse (11 August 2017). "James Cameron has a few thoughts about Ridley Scott's Alien: Covenant". Syfy. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Ridley Scott: 'Magic comes over the horizon every day' | Hero Complex – movies, comics, pop culture". Los Angeles Times. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott, p. 121-142, Lexington Books, 2013.

- ^ The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott, p. 136-142, Lexington Books, 2013.

- ^ The Culture and Philosophy of Ridley Scott, p. 140-142, Lexington Books, 2013.

- ^ "No. 56797". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2002. p. 1.

- ^ "Queen knights Gladiator director". BBC News. 8 July 2003. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "No. 64269". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 2023. p. N9.

- ^ "Science Fiction Hall of Fame to Induct Ed Emshwiller, Gene Roddenberry, Ridley Scott and Gene Wolfe". Retrieved 26 April 2015.[dead link]. Press release March/April/May 2007. Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame (empsfm.org). Archived 14 October 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2013

- ^ "RIDLEY SCOTT ZUM ACHTZIGSTEN :Der selbstleuchtende Sehnerv". Frankfurter Allgemeine - FAZ.net. 30 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Hollywood stars for Simon Fuller and Sir Ridley Scott" Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "1980 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "2016 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. 29 December 2015. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake's 80th birthday". The Guardian. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "RCA Convocation 2015". RCA [view from 13:55 and 31:45]. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Honorary Doctors". RCA. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

External links

[edit]- "Ridley Scott biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Ridley Scott at IMDb

- Ridley Scott at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Ridley Scott Associates (RSA)

- They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

- Lauchlan, Grant. "Interview". STV. Archived from the original (Video) on 25 October 2008.

Discussing Kingdom of Heaven and Blade Runner

- Sullivan, Chris (5 October 2006). "Ridley Scott uncut: exclusive online interview". Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008.

- "Total Film: Interview with Ridley Scott". 15 July 2007. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- Interview with Ridley Scott at Texas Archive of the Moving Image

- Ridley Scott

- 1937 births

- Living people

- Alumni of the Royal College of Art

- Apple Inc. advertising

- Artists awarded knighthoods

- BAFTA Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema Award

- BAFTA fellows

- British animated film directors

- British animated film producers

- British film production company founders

- David di Donatello winners

- Directors Guild of America Award winners

- English expatriates in France

- English expatriates in the United States

- English film directors

- English film producers

- English television directors

- English television producers

- English-language film directors

- Golden Globe Award–winning producers

- British horror film directors

- Hugo Award winners

- Knights Bachelor

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

- People from South Shields

- Postmodernist filmmakers

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Science fiction film directors

- Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees

- Television commercial directors

- Directors of Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Scott family (show business)