Sacrifice

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2016) |

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship.[1][2] Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly existed before that. Evidence of ritual human sacrifice can also be found back to at least pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica as well as in European civilizations. Varieties of ritual non-human sacrifices are practiced by numerous religions today.

Terminology

[edit]

The Latin term sacrificium (a sacrifice) derived from Latin sacrificus (performing priestly functions or sacrifices), which combined the concepts sacra (sacred things) and facere (to make, to do).[3] The Latin word sacrificium came to apply to the Christian eucharist in particular, sometimes named a "bloodless sacrifice" to distinguish it from blood sacrifices. In individual non-Christian ethnic religions, terms translated as "sacrifice" include the Indic yajna, the Greek thusia, the Germanic blōtan, the Semitic qorban/qurban, Slavic żertwa, etc.

The term usually implies "doing without something" or "giving something up" (see also self-sacrifice). But the word sacrifice also occurs in metaphorical use to describe doing good for others or taking a short-term loss in return for a greater power gain, such as in a game of chess.[4][5][6]

Animal sacrifice

[edit]

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing of an animal as part of a religion. It is practiced by adherents of many religions as a means of appeasing a god or gods or changing the course of nature. It also served a social or economic function in those cultures where the edible portions of the animal were distributed among those attending the sacrifice for consumption. Animal sacrifice has turned up in almost all cultures, from the Hebrews to the Greeks and Romans (particularly the purifying ceremony Lustratio), Egyptians (for example in the cult of Apis) and from the Aztecs to the Yoruba. The religion of the ancient Egyptians forbade the sacrifice of animals other than sheep, bulls, calves, male calves and geese.[7]

Animal sacrifice is still practiced today by the followers of Santería and other lineages of Orisa as a means of curing the sick and giving thanks to the Orisa (gods). However, in Santeria, such animal offerings constitute an extremely small portion of what are termed ebos—ritual activities that include offerings, prayer and deeds. Christians from some villages in Greece also sacrifice animals to Orthodox saints in a practice known as kourbánia. The practice, while publicly condemned, is often tolerated.[citation needed]

Human sacrifice

[edit]

Human sacrifice was practiced by many ancient cultures. People would be ritually killed in a manner that was supposed to please or appease a god or spirit.

Some occasions for human sacrifice found in multiple cultures on multiple continents include:[citation needed]

- Human sacrifice to accompany the dedication of a new temple or bridge.

- Sacrifice of people upon the death of a king, high priest or great leader; the sacrificed were supposed to serve or accompany the deceased leader in the next life.

- Human sacrifice in times of natural disaster. Droughts, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, etc. were seen as a sign of anger or displeasure by deities, and sacrifices were supposed to lessen the divine ire.

There is evidence to suggest Pre-Hellenic Minoan cultures practiced human sacrifice. Corpses were found at a number of sites in the citadel of Knossos in Crete. The north house at Knossos contained the bones of children who appeared to have been butchered. The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur (set in the labyrinth at Knossos) suggests human sacrifice. In the myth, Athens sent seven young men and seven young women to Crete as human sacrifices to the Minotaur. This ties up with the archaeological evidence that most sacrifices were of young adults or children.

The Phoenicians of Carthage were reputed to practise child sacrifice, and though the scale of sacrifices may have been exaggerated by ancient authors for political or religious reasons, there is archaeological evidence of large numbers of children's skeletons buried in association with sacrificial animals. Plutarch (ca. 46–120 AD) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian, Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and Philo. They describe children being roasted to death while still conscious on a heated bronze idol.[8]

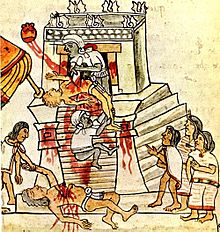

Human sacrifice was practiced by various Pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica. The Aztec in particular are known for the practice of human sacrifice.[9] Current estimates of Aztec sacrifice are between a couple of thousand and twenty thousand per year.[10] Some of these sacrifices were to help the sun rise, some to help the rains come, and some to dedicate the expansions of the great Templo Mayor, located in the heart of Tenochtitlán (the capital of the Aztec Empire). There are also accounts of captured conquistadores being sacrificed during the wars of the Spanish invasion of Mexico.

In Scandinavia, the old Scandinavian religion contained human sacrifice, as both the Norse sagas and German historians relate. See, e.g. Temple at Uppsala and Blót.

In the Aeneid by Virgil, the character Sinon claims (falsely) that he was going to be a human sacrifice to Poseidon to calm the seas.

Human sacrifice is no longer officially condoned in any country,[11] and any cases which may take place are regarded as murder.

By religion

[edit]Ancient China and Confucianism

[edit]During the Shang and Zhou dynasty, the ruling class had a complicated and hierarchical sacrificial system. Sacrificing to ancestors was an important duty of nobles, and an emperor could hold hunts, start wars, and convene royal family members in order to get the resources to hold sacrifices, [12] serving to unify states in a common goal and demonstrate the strength of the emperor's rule. Archaeologist Kwang-chih Chang states in his book Art, Myth and Ritual: the Path to Political Authority in Ancient China (1983) that the sacrificial system strengthened the authority of ancient China's ruling class and promoted production, e.g. through casting ritual bronzes.

Confucius supported the restoration of the Zhou sacrificial system, which excluded human sacrifice, with the goal of maintaining social order and enlightening people. Mohism considered any kind of sacrifice to be too extravagant for society.

Chinese folk religion

[edit]Members of Chinese folk religions often use pork, chicken, duck, fish, squid, or shrimp in sacrificial offerings. For those who believe the high deities to be vegetarian, some altars are two-tiered: The high one offers vegetarian food, and the low one holds animal sacrifices for the high deities' soldiers. Some ceremonies of supernatural spirits and ghosts, like the Ghost Festival, use whole goats or pigs. There are competitions of raising the heaviest pig for sacrifice in Taiwan and Teochew. [13]

Christianity

[edit]

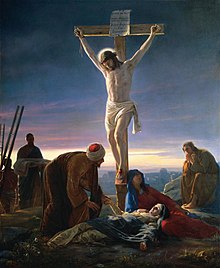

In Nicene Christianity, God became incarnate as Jesus, sacrificing his son to accomplish the reconciliation of God and humanity, which had separated itself from God through sin (see the concept of original sin). According to a view that has featured prominently in Western theology since early in the 2nd millennium, God's justice required an atonement for sin from humanity if human beings were to be restored to their place in creation and saved from damnation. However, God knew limited human beings could not make sufficient atonement, for humanity's offense to God was infinite, so God created a covenant with Abraham, which he fulfilled when he sent his only Son to become the sacrifice for the broken covenant.[citation needed] According to this theology, Christ's sacrifice replaced the insufficient animal sacrifice of the Old Covenant; Christ the "Lamb of God" replaced the lambs' sacrifice of the ancient Korban Todah (the Rite of Thanksgiving), chief of which is the Passover in the Mosaic law.

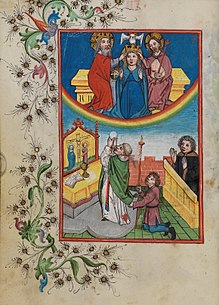

In the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Lutheran Churches, the Methodist Churches, and the Irvingian Churches,[14][15] the Eucharist or Mass, as well as the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Catholic Churches and Eastern Orthodox Church, is seen as a sacrifice. Among the Anglicans the words of the liturgy make explicit that the Eucharist is a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving and is a material offering to God in union with Christ using such words, as "with these thy holy gifts which we now offer unto Thee" (1789 BCP) or "presenting to you from the gifts you have given us we offer you these gifts" (Prayer D BCP 1976) as clearly evidenced in the revised Books of Common Prayer from 1789 in which the theology of Eucharist was moved closer to the Catholic position. Likewise, the United Methodist Church in its Eucharistic liturgy contains the words "Let us offer ourselves and our gifts to God" (A Service of Word and Table I). The United Methodist Church officially teaches that "Holy Communion is a type of sacrifice" that re-presents, rather than repeats the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross; She further proclaims that:

We also present ourselves as sacrifice in union with Christ (Romans 12:1; 1 Peter 2:5) to be used by God in the work of redemption, reconciliation, and justice. In the Great Thanksgiving, the church prays: "We offer ourselves in praise and thanksgiving as a holy and living sacrifice, in union with Christ's offering for us . . ." (UMH; page 10).[14]

A formal statement by the USCCB affirms that "Methodists and Catholics agree that the sacrificial language of the Eucharistic celebration refers to 'the sacrifice of Christ once-for-all,' to 'our pleading of that sacrifice here and now,' to 'our offering of the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving,' and to 'our sacrifice of ourselves in union with Christ who offered himself to the Father.'"[16]

Roman Catholic theology speaks of the Eucharist not being a separate or additional sacrifice to that of Christ on the cross; it is rather exactly the same sacrifice, which transcends time and space ("the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world" – Rev. 13:8), renewed and made present, the only distinction being that it is offered in an unbloody manner. The sacrifice is made present without Christ dying or being crucified again; it is a re-presentation of the "once and for all" sacrifice of Calvary by the now risen Christ, who continues to offer himself and what he has done on the cross as an oblation to the Father. The complete identification of the Mass with the sacrifice of the cross is found in Christ's words at the last supper over the bread and wine: "This is my body, which is given up for you," and "This is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed...unto the forgiveness of sins." The bread and wine, offered by Melchizedek in sacrifice in the old covenant (Genesis 14:18; Psalm 110:4), are transformed through the Mass into the body and blood of Christ (see transubstantiation; note: the Orthodox Church and Methodist Church do not hold as dogma, as do Catholics, the doctrine of transubstantiation, preferring rather to not make an assertion regarding the "how" of the sacraments),[17][18] and the offering becomes one with that of Christ on the cross. In the Mass as on the cross, Christ is both priest (offering the sacrifice) and victim (the sacrifice he offers is himself), though in the Mass in the former capacity he works through a solely human priest who is joined to him through the sacrament of Holy Orders and thus shares in Christ's priesthood as do all who are baptized into the death and resurrection of Jesus, the Christ. Through the Mass, the effects of the one sacrifice of the cross can be understood as working toward the redemption of those present, for their specific intentions and prayers, and to assisting the souls in purgatory. For Catholics, the theology of sacrifice has seen considerable change as the result of historical and scriptural studies.[19] For Lutherans, the Eucharist is a "sacrifice of thanksgiving and praise…in that by giving thanks a person acknowledges that he or she is in need of the gift and that his or her situation will change only by receiving the gift".[15] The Irvingian Churches, teach the "real presence of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ in Holy Communion":

In Holy Communion, it is not only the body and blood of Christ, but also His sacrifice itself, that are truly present. However, this sacrifice has only been brought once and is not repeated in Holy Communion. Neither is Holy Communion merely a reminder of the sacrifice. Rather, during the celebration of Holy Communion, Jesus Christ is in the midst of the congregation as the crucified, risen, and returning Lord. Thus His once-brought sacrifice is also present in that its effect grants the individual access to salvation. In this way, the celebration of Holy Communion causes the partakers to repeatedly envision the sacrificial death of the Lord, which enables them to proclaim it with conviction (1 Corinthians 11: 26). —¶8.2.13, The Catechism of the New Apostolic Church[20]

The concept of self-sacrifice and martyrs are central to Christianity. Often found in Roman Catholicism is the idea of joining one's own life and sufferings to the sacrifice of Christ on the cross. Thus one can offer up involuntary suffering, such as illness, or purposefully embrace suffering in acts of penance. Some Protestants criticize this as a denial of the all-sufficiency of Christ's sacrifice, but according to Roman Catholic interpretation it finds support in St. Paul: "Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ's afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church" (Col 1:24). Pope John Paul II explained in his Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris (11 February 1984):

In the Cross of Christ not only is the Redemption accomplished through suffering, but also human suffering itself has been redeemed. ...Every man has his own share in the Redemption. Each one is also called to share in that suffering through which the Redemption was accomplished. ...In bringing about the Redemption through suffering, Christ has also raised human suffering to the level of the Redemption. Thus each man, in his suffering, can also become a sharer in the redemptive suffering of Christ. ...The sufferings of Christ created the good of the world's redemption. This good in itself is inexhaustible and infinite. No man can add anything to it. But at the same time, in the mystery of the Church as his Body, Christ has in a sense opened his own redemptive suffering to all human suffering" (Salvifici Doloris 19; 24).

Some Christians reject the idea of the Eucharist as a sacrifice, inclining to see it as merely a holy meal (even if they believe in a form of the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine, as Reformed Christians do). The more recent the origin of a particular tradition, the less emphasis is placed on the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist. The Roman Catholic response is that the sacrifice of the Mass in the New Covenant is that one sacrifice for sins on the cross which transcends time offered in an unbloody manner, as discussed above, and that Christ is the real priest at every Mass working through mere human beings to whom he has granted the grace of a share in his priesthood. As priest carries connotations of "one who offers sacrifice", some Protestants, with the exception of Lutherans and Anglicans, usually do not use it for their clergy. Evangelical Protestantism emphasizes the importance of a decision to accept Christ's sacrifice on the Cross consciously and personally as atonement for one's individual sins if one is to be saved—this is known as "accepting Christ as one's personal Lord and Savior".

The Eastern Orthodox Churches see the celebration of the Eucharist as a continuation, rather than a reenactment, of the Last Supper, as Fr. John Matusiak (of the OCA) says: "The Liturgy is not so much a reenactment of the Mystical Supper or these events as it is a continuation of these events, which are beyond time and space. The Orthodox also see the Eucharistic Liturgy as a bloodless sacrifice, during which the bread and wine we offer to God become the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ through the descent and operation of the Holy Spirit, Who effects the change." This view is witnessed to by the prayers of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, when the priest says: "Accept, O God, our supplications, make us to be worthy to offer unto thee supplications and prayers and bloodless sacrifices for all thy people," and "Remembering this saving commandment and all those things which came to pass for us: the cross, the grave, the resurrection on the third day, the ascension into heaven, the sitting down at the right hand, the second and glorious coming again, Thine own of Thine own we offer unto Thee on behalf of all and for all," and "… Thou didst become man and didst take the name of our High Priest, and deliver unto us the priestly rite of this liturgical and bloodless sacrifice…"

Hinduism

[edit]The modern practice of Hindu animal sacrifice is mostly associated with Shaktism, and in currents of folk Hinduism strongly rooted in local popular or tribal traditions. Animal sacrifices were part of the ancient Vedic religion in India, and are mentioned in scriptures such as the Yajurveda. For instance, these scriptures mention the use of mantras for goat sacrifices as a means of abolishing human sacrifice and replacing it with animal sacrifice.[21] Even if animal sacrifice was common historically in Hinduism, contemporary Hindus believe that both animals and humans have souls and may not be offered as sacrifices.[22] This concept is called ahimsa, the Hindu law of non-injury and no harm. Some Puranas forbid animal sacrifice.[23]

Islam

[edit]An animal sacrifice in Arabic is called ḏabiḥa (ذَبِيْحَة) or Qurban (قُرْبَان) . The term may have roots from the Jewish term Korban; in some places like Bangladesh, India or Pakistan, qurbani is always used for Islamic animal sacrifice. In the Islamic context, an animal sacrifice referred to as ḏabiḥa (ذَبِيْحَة) meaning "sacrifice as a ritual" is offered only in Eid ul-Adha. The sacrificial animal may be a sheep, a goat, a camel, or a cow. The animal must be healthy and conscious. "...Therefore to the Lord turn in Prayer and Sacrifice." (Quran 108:2) Qurban is an Islamic prescription for the affluent to share their good fortune with the needy in the community.

On the occasion of Eid ul Adha (Festival of Sacrifice), affluent Muslims all over the world perform the Sunnah of Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) by sacrificing a cow or sheep. The meat is then divided into three equal parts. One part is retained by the person who performs the sacrifice. The second is given to his relatives. The third part is distributed to the poor.

The Quran states that the sacrifice has nothing to do with the blood and gore (Quran 22:37: "It is not their meat nor their blood that reaches God. It is your piety that reaches Him..."). Rather, it is done to help the poor and in remembrance of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his son Ismael at God's command.

The Urdu and Persian word "Qurbani" comes from the Arabic word 'Qurban'. It suggests that associate act performed to hunt distance to Almighty God and to hunt His sensible pleasure. Originally, the word 'Qurban' enclosed all acts of charity as a result of the aim of charity is nothing however to hunt Allah's pleasure. But, in precise non-secular nomenclature, the word was later confined to the sacrifice of associate animal slaughtered for the sake of Allah.[24]

A similar symbology, which is a reflection of Abraham and Ismael's dilemma, is the stoning of the Jamaraat which takes place during the pilgrimage.

Judaism

[edit]Ritual sacrifice was practiced in Ancient Israel, with the opening chapters of the book Leviticus detailing parts of an overview referring to the exact methods of bringing sacrifices. Although sacrifices could include bloodless offerings (grain and wine), the most important were animal sacrifices.[25] Blood sacrifices were divided into burnt offerings (Hebrew: עלה קרבנות) in which the whole unmaimed animal was burnt, guilt offerings (in which part was burnt and part left for the priest) and peace offerings (in which similarly only part of the undamaged animal was burnt and the rest eaten in ritually pure conditions).

After the destruction of the Second Temple, ritual sacrifice ceased except among the Samaritans.[26] Maimonides, a medieval Jewish rationalist, argued that God always held sacrifice inferior to prayer and philosophical meditation. However, God understood that the Israelites were used to the animal sacrifices that the surrounding pagan tribes used as the primary way to commune with their gods. As such, in Maimonides' view, it was only natural that Israelites would believe that sacrifice was a necessary part of the relationship between God and man. Maimonides concludes that God's decision to allow sacrifices was a concession to human psychological limitations. It would have been too much to have expected the Israelites to leap from pagan worship to prayer and meditation in one step. In the Guide for the Perplexed, he writes:

- "But the custom which was in those days general among men, and the general mode of worship in which the Israelites were brought up consisted in sacrificing animals... It was in accordance with the wisdom and plan of God...that God did not command us to give up and to discontinue all these manners of service. For to obey such a commandment would have been contrary to the nature of man, who generally cleaves to that to which he is used; it would in those days have made the same impression as a prophet would make at present [the 12th Century] if he called us to the service of God and told us in His name, that we should not pray to God nor fast, nor seek His help in time of trouble; that we should serve Him in thought, and not by any action." (Book III, Chapter 32. Translated by M. Friedlander, 1904, The Guide for the Perplexed, Dover Publications, 1956 edition.)

In contrast, many others such as Nachmanides (in his Torah commentary on Leviticus 1:9) disagreed, contending that sacrifices are an ideal in Judaism, completely central.

The teachings of the Torah and Tanakh reveal the Israelites's familiarity with human sacrifices, as exemplified by the near-sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham (Genesis 22:1–24) and some believe, the actual sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter (Judges 11:31–40), while many believe that Jephthah's daughter was committed for life in service equivalent to a nunnery of the day, as indicated by her lament over her "weep for my virginity" and never having known a man (v37). The king of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering, albeit to the pagan god Chemosh.[27] In the book of Micah, one asks, 'Shall I give my firstborn for my sin, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?' (Micah 6:7), and receives a response, 'It hath been told thee, O man, what is good, and what the LORD doth require of thee: only to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God.' (Micah 6:8) Abhorrence of the practice of child sacrifice is emphasized by Jeremiah. See Jeremiah 7:30–32.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sacrifice Definition & Meaning". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Cowdell; Fleming, Chris; Hodge, Joel, eds. (2014). Violence, Desire, and the Sacred. Vol. 2: René Girard and Sacrifice in Life, Love and Literature. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781623562557. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "sacrifice". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ^ "Sacrifices Needed to Fix Auto Crisis - Economy - Javno". Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Governor signs into law legislation protecting rights of nursing mothers in the workplace". Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ Helm, Sarah (17 June 1997). "Amsterdam summit: Blair forced to sacrifice powers on immigration". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Herodotus (15 May 2008). The histories. Translated by Robin Waterfield (Oxford World's Classics ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953566-8.

- ^ Stager, Lawrence; Wolff, Samuel R. (1984). "Child sacrifice in Carthage: religious rite or population control?". Journal of Biblical Archeological Review. January: 31–46.

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (21 June 2018). "Feeding the gods: Hundreds of skulls reveal massive scale of human sacrifice in Aztec capital". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau5404.

- ^ Dodds Pennock, Caroline (2012). "Mass Murder or Religious Homicide? Rethinking Human Sacrifice and Interpersonal Violence in Aztec Society". Historical Social Research. 37 (3): 276–302. JSTOR 41636609. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Cahill, Thomas (November 1998). "Ending Human Sacrifice". Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Plutschow, Herbert (1996). "Archaic Chinese Sacrificial Practices in the Light of Generative Anthropology". Anthropoetics. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

Among the kings' most important functions were sacrificial ritual, and ritual-related war and hunting, understood, among others, as a state-unifying, ritual action in search of sacrificial supply.

- ^ "強迫灌食肥豬變八百公斤「神豬」 被批虐待動物" (in Chinese). BBC. 11 September 2020. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ a b This Holy Mystery, Study Guide: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy Communion. The General Board of Discipleship of The United Methodist Church. 2004. p. 9.

- ^ a b O'Malley, Timothy P. (7 July 2016). "Catholics, Lutherans and the Eucharist: There's a lot to share". America Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Methodist-Catholic Dialogues. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and The General Commission on Christian Unity and Interreligious Concerns of The United Methodist Church. 2001. p. 20.

- ^ Losch, Richard R. (1 May 2002). A Guide to World Religions and Christian Traditions. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 9780802805218.

In the Roman Catholic Church the official explanation of how Christ is present is called transubstantiation. This is simply an explanation of how, not a statement that, he is present. Anglicans and Orthodox do not attempt to define how, but simply accept the mystery of his presence.

- ^ Neal, Gregory S. (19 December 2014). Sacramental Theology and the Christian Life. WestBow Press. p. 111. ISBN 9781490860077.

For Anglicans and Methodists the reality of the presence of Jesus as received through the sacramental elements is not in question. Real presence is simply accepted as being true, its mysterious nature being affirmed and even lauded in official statements like This Holy Mystery: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy Communion.

- ^ Zupez, John (December 2019). "Is the Mass a Propitiatory or Expiatory Sacrifice?". Emmanuel. 125: 378–381. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "8.2.13 The real presence of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ in Holy Communion". The Catechism of the New Apostolic Church. New Apostolic Church. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Hinduism". HathiTrust. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Das, Venna (2013). "Being Together with Animals: Death, Violence and Noncruelty in Hindu Imagination". "Being Together with Animals: Death, Violence and Noncruelty in Hindu Imagination". pp. 17–31. doi:10.4324/9781003085881-2. ISBN 978-1-003-08588-1. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Ahimsa in Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism: A Compassionate View of Life", Comparative Approaches to Compassion, Bloomsbury Academic, 2022, doi:10.5040/9781350288898.ch-1, ISBN 978-1-350-28886-7, retrieved 19 October 2024

- ^ "Online Qurbani". 1 November 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- ^ "sacrifice". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 17 (2 ed.). p. 641.

- ^ "The Samaritan's Festivals". The Samaritans. Archived from the original on 4 March 2006.

- ^ Harton, George M. "The meaning of II Kings 3:27" (PDF). Biblical Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Korte, Anne-Marie (1998). Bekkenkamp, Jonneke; de Haardt, Maaike (eds.). Significance Obscured: Rachel's Theft of the Teraphim Divinity and Corporeality in Gen.31 32 [Translation: Mischa F.C. Hoyinck]. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 157–182. Korte summarizes Jay at length and refers to Dresden.

- Dresen, Grietje (1993). "Heilig bloed, ontheiligend bloed: Over het ritueel van de kerkgang en het offer in de katholieke traditie". Tijdschrift voor Vrouwenstudies. 14: 25–41.

- Aldrete, Gregory S. (2014). "Hammers, Axes, Bulls, and Blood: Some Practical Aspects of Roman Animal Sacrifice." Journal of Roman Studies 104:28–50.

- Bataille, Georges. (1989). Theory of Religion. New York: Zone Books.

- Bloch, Maurice. (1992). Prey into Hunter: The Politics of Religious Experience. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Bubbio, Paolo Diego. (2014). Sacrifice in the Post-Kantian Tradition: Perspectivism, Intersubjectivity, and Recognition. SUNY Press.

- Burkert, Walter. (1983). Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth. Translated by P. Bing. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Burkert, Walter, Marcel Sigrist, Harco Willems, et al. (2007). "Sacrifice, Offerings, and Votives." In Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Edited by S. I. Johnston, 325–349. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

- Carter, Jeffrey. (2003). Understanding Religious Sacrifice: A Reader. London: Continuum.

- Davies, Nigel. (1981). Human Sacrifice: In History and Today. London: Macmillan.

- Faraone, Christopher A., and F. S. Naiden, eds. (2012). Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Feeney, Denis. (2004). "Interpreting Sacrificial Ritual in Roman Poetry: Disciplines and their Models." In Rituals in Ink: A Conference on Religion and Literary Production in Ancient Rome Held at Stanford University in February 2002. Edited by Alessandro Barchiesi, Jörg Rüpke, and Susan Stephens, 1–21. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

- Heinsohn, Gunnar. (1992). "The Rise of Blood Sacrifice and Priest-Kingship in Mesopotamia: A 'cosmic decree'?" Religion 22 (2): 109.

- Hubert, Henri, and Marcel Mauss. (1964). Sacrifice: Its Nature and Function. Translated by W. Hall. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Jay, Nancy (1992). Throughout All Your Generations Forever: Sacrifice, Religion, and Paternity. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Jensen, Adolf E. (1963). Myth and Cult Among Primitive Peoples. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Kunst, Jennifer W., and Zsuzsanna Várhelyi, eds. (2011). Ancient Mediterranean Sacrifice. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- McClymond, Kathryn. (2008). Beyond Sacred Violence: A Comparative Study of Sacrifice. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Mylonopoulos, Joannis. (2013). "Gory Details? The Iconography of Human Sacrifice in Greek Art." In Sacrifices humains. Perspectives croissées et répresentations. Edited by Pierre Bonnechere and Gagné Renaud, 61–85. Liège, Belgium: Presses universitaires de Liège.

- Watson, Simon R. (2019). "God in Creation: A Consideration of Natural Selection as the Sacrificial Means of a Free Creation". Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses. 48 (2): 216–236. doi:10.1177/0008429819830356. S2CID 202271434.

External links

[edit]- "In India, Case Links Mysticism, Murder" by John Lancaster

- Ancient texts on sacrifice Tiresias: The Ancient Mediterranean Religions Source Database

- Sacrifice definition from the Bible Dictionary