Naturmuseum Senckenberg

The Naturmuseum Senckenberg in 2012 | |

| |

Former name | Öffentliches Naturalienkabinett |

|---|---|

| Established | 1821/1907 |

| Location | Senckenberganlage 25, Frankfurt, Germany |

| Coordinates | 50°07′03″N 8°39′06″E / 50.11750°N 8.65167°E |

| Type | Natural history |

| Key holdings | Triceratops (skulls), Edmontosaurus mummy SMF R 4036, Psittacosaurus SMF R 4970, Diplodocus SMF R 462, Placodus gigas SMF R 1035, Eurohippus messelensis SMF ME 11034, Dodo, Quagga |

| Collections | Dinosaurs, Insects, Birds, Reptils, Mammals, Human evolution, Messel Research |

| Collection size | |

| Visitors | |

| Founder | Senckenberg Nature Research Society, (namesake: Johann Christian Senckenberg) |

| Director | Brigitte Franzen[7] |

| Architect | Ludwig Neher |

| Owner | Senckenberg Nature Research Society |

| Employees | 843[1] |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | museumfrankfurt.senckenberg.de |

The Naturmuseum Senckenberg (SMF)[8] is a museum of natural history, located in Frankfurt am Main. It is the second-largest of its kind in Germany. In 2010, almost 517,000 people visited the museum, which is owned by the Senckenberg Nature Research Society.[9] Senckenberg's slogan is "world of biodiversity".[10] As of 2019[update], the museum exhibits 18 reconstructed dinosaurs.[11]

History

[edit]In 1763, Johann Christian Senckenberg donated 95,000 guilders–his entire fortune–to establish a community hospital and promote scientific projects.[12][13] Senckenberg died in 1772. In 1817, 32 Frankfurt citizens founded the non-profit Senckenberg Nature Research Society, German: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN), which is a member of the Leibniz Association.[14][15][16] Soon after, Johann Georg Neuburg donated his collection of bird and mammal specimens to the society.[15] The Naturmuseum Senckenberg was founded in 1821, just four years later.[a][18] Initially located near the Eschenheimer Turm,[19] the museum moved to a new building on Senckenberganlage in 1907.[20] In 1896 a mummified Egyptian child in their collection (inventory number ÄS 18) was the subject of the first mummy X-ray.[21] During World War II, the building was partly destroyed.[b] However, the exhibits had been evacuated before.[15]

Building

[edit]The neo-baroque building[22] housing the Senckenberg Museum was erected between 1904 and 1907 by Ludwig Neher outside of the center of Frankfurt in the same area as the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, which was founded in 1914.[23] The museum is owned and operated by the Senckenberg Nature Research Society.[24] The exhibition area covers 6,000 m2 (65,000 sq ft).[25]

-

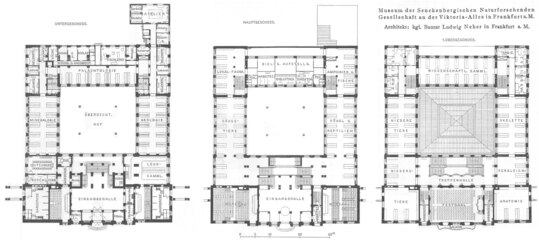

Floor plans of the basement, ground floor and first floor of the Senckenberg Museum at the time of construction, published 1908

-

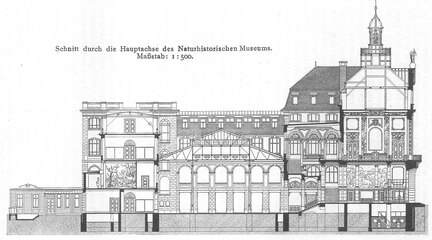

Cross section through the main axis of the Senckenberg Museum, published 1908

Source:[26]

Expansion plans

[edit]As of 2018[update], the museum has been expanded to 10,000 m2 (110,000 sq ft).[c][28] New planned sections: Human, Earth, Cosmos, Future.[29][30]

Directors

[edit]- 2021–present Brigitte Franzen[31]

Collections

[edit]The Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt has a large collection of animal, plant[32] and geology[33] exhibits from every epoch of Earth's history.

Dinosaurs

[edit]Diplodocus

[edit]Main attraction is a Diplodocus from Bone Cabin Quarry, Wyoming,[34][35] donated by the American Museum of Natural History on the occasion of the present museum building's inauguration on 13 October 1907,[17][36][37] The 18 m (59 ft) mounted skeleton with additions contains bones of three different sauropod genera (Diplodocus and closely related Apatosaurus and Barosaurus).[34][38]

Psittacosaurus

[edit]As of 2022[update], a key holding is a fossilized Psittacosaurus (specimen SMF R 4970) from Liaoning, China, with clear bristles around its tail and visible fossilized stomach contents.[39][40][41] The specimen was first reported in 2002.[40][42] The exact date and locality of the discovery within Liaoning is unknown.[39] A controversial debate about the legal ownership arose.[39][43] In 2021, researchers described its cloaca in more detail and found similarities with the body outlet of birds.[44][45][46] In 2022, for the first time a belly button was found in a dinosaur fossil.[40][47] A physical life reconstruction of the animal was prepared by paleoartist Robert Nicholls.[48][49]

Edmontosaurus and Triceratops

[edit]Another originals are an Edmontosaurus annectens mummy (specimen SMF R 4036) from Lance Formation, Wyoming.[50][51][52] and two Triceratops skulls.[53][11] The museum bought the three specimen from fossil collector Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his sons in the early 20th century.[54][55] The museum also exhibits a cast of a complete Triceratops,[11] the museum's mascot.[56]

Casts

[edit]Big public attractions also include the casts of Tyrannosaurus rex[d] and Diplodocus longus (in front of the museum), an Iguanodon, the crested Hadrosaur Parasaurolophus and an Oviraptor.[35]

Further casts or single bones:[35]

- Archaeopteryx lithographica

- Brachiosaurus brancai

- Compsognathus longipes

- Euoplocephalus tutus

- Plateosaurus engelhardti

- Protoceratops

- Sinosauropteryx prima

- Stegosaurus stenops

- Amargasaurus cazaui

- Argentinosaurus huinculensis

- Austroraptor cabazai

- Carnotaurus sastrei

- Eoraptor lunensis

- Giganotosaurus carolinii

- Kritosaurus australis

- Panphagia protos

- Velociraptor[57]

- Deinonychus[57]

Birds

[edit]A living reconstruction of the extinct dodo and many other stuffed birds are shown in a permanent exhibition in the upper level.[58] Additionally, the museum owns a large and diverse collection of birds with 90,000 bird skins, 5,050 egg sets, 17,000 skeletons, and 3,375 spirit specimens (a specimen preserved in fluid).[59][60] This is 75% of the known bird species, only a minor part is exhibited.[60]

Reptiles

[edit]Anaconda is one of the oldest and most popular exhibits.[61] Since the remodeling finished in 2003, a new reptile exhibit addresses both the biodiversity of reptiles and amphibians and the topic of nature conservation.[62]

Messel research

[edit]The museum houses many originals from the nearby Messel pit,[63] Germany's first UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site,[64] among them a predecessor to the modern horse that lived about 50 million years ago and stood less than 60 cm (24 in) tall.[65][66][67] In 2015, researchers found an foal fetus in the body of the petrified primeval horse mare.[68][69][70] Also primates, crocodiles, bats, snakes, turtles and other fossils were found at Messel pit.[71]

Mammals

[edit]Display collections full of stuffed animals are arranged in the upper levels; among other things one can see one of twenty existing examples of the quagga, which has been extinct since 1883.[72][73]

The mammal collection focuses on bats, primates, rodents, and insectivores (not exhibited).[74]

Human evolution

[edit]Unique in Europe is a cast of the famous Lucy,[e] an almost complete skeleton of the upright, 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall, hominid Australopithecus afarensis.[76] The exhibition also includes reconstructions of the heads of human ancestors.[76]

Gallery

[edit]-

Original Triceratops skulls

-

Reconstructed skeleton of Giganotosaurus carolinii

-

Original Diplodocus

-

Original Edmontosaurus mummy

-

Original Psittacosaurus

-

Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus) devours a capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

-

Original Messel fossil Eurohippus messelensis, primeval horse

-

Reconstructed skeleton of an Australopithecus afarensis ("Lucy")

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The museum was opened to the public on 22 November 1821.[17]

- ^ Bombing of Frankfurt am Main in World War II, on 22 March 1944.[15]

- ^ Including buildings Alte Physik (south) and Jügelbau (north) by architect Peter Kulka.[27]

- ^ Copy of a Tyrannosaurus located at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.[11]

- ^ The original Lucy is stored in a safe at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.[75]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c SENCKENBERG ANNUAL REPORT 2021 (PDF) (Report). Naturmuseum Senckenberg. May 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "20 von 10.000: Senckenberg-Museum zeigt Wandel in 200 Jahren". Süddeutsche.de (in German). dpa. 29 June 2021. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Senckenberg Jahresbericht 2022–2023

- ^ SENCKENBERG 2020 (PDF) (Report). Naturmuseum Senckenberg. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ SENCKENBERG 2019 (PDF) (Report). Naturmuseum Senckenberg. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ SENCKENBERG 2018 (PDF) (Report). Naturmuseum Senckenberg. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Brigitte Franzen übernimmt Leitung des Senckenberg-Museums". Süddeutsche.de (in German). dpa. 24 November 2020. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Sabaj, Mark Henry (14 October 2020). "Codes for Natural History Collections in Ichthyology and Herpetology". Copeia. 108 (3). American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH). doi:10.1643/asihcodons2020. ISSN 0045-8511. S2CID 225328378.

- ^ Eiff, Doris von (3 February 2011). "Besucherzahlen im Senckenberg Naturmuseum weiter auf hohem Niveau". Informationsdienst Wissenschaft. Idw-online.de. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Benn, Roland (16 November 2022). "Das Haus der Evolutionäre". Die Zeit (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Deutschlands beste Dino-Ausstellungen: Senckenberg". Der Spiegel (in German). 30 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "200 Jahre Senckenberg-Gesellschaft – Naturkunde für Jung und Alt – 22.11.2017". Deutsche Welle (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Bericht der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Frankfurt am Main : Senckenbergische Naturforschende Gesellschaft : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Senckenberg Gesellschaft feiert 200. Geburtstag". Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung – BMBF (in German). 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Historie". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 1 March 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Leibniz-Gemeinschaft: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung". Leibniz-Gemeinschaft (in German). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b Naumberg, Elsie M. B. (1931). "The Senckenberg Museum, Frankfort-on-Main, Germany". The Auk. 48 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 379–384. doi:10.2307/4076482. ISSN 0004-8038. JSTOR 4076482.

- ^ "Museum for Tomorrow 200 Jahre Museum · Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt. 29 September 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Senckenberg, Johann Christian". Deutsche Biographie (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Die Geschichte der Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt (in German). Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Zesch, Stephanie; Panzer, Stephanie; Rosendahl, Wilfried; Nance, John W; Schönberg, Stefan O; Henzler, Thomas (2016). "From first to latest imaging technology: Revisiting the first mummy investigated with X-ray in 1896 by using dual-source computed tomography". European Journal of Radiology Open. 3: 172–181. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2016.07.002. PMC 4968187. PMID 27504475.

- ^ Zoske, Sascha (8 November 2003). "Senckenberg-Museum: Hausputz bei den Sauriern". FAZ.NET (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Schweiger, Doris (29 January 2018). "Das "Senckenberg Naturmuseum" in Frankfurt am Main". MeinBezirk.at (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Johann Christian Senckenberg und seine Stiftung". www.ub.uni-frankfurt.de. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Start einer neuen Ära · Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt (in German). 19 April 2021. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "Deutsche Bauzeitung". Internet Archive. 14 January 2022. pp. 594, 596. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Senckenberg". Peter Kulka (in German). 11 December 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "DAM Preis 2020". DAM-Preis (in German). Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Das neue Senckenberg: Mehr Platz für die großen Fragen". Die Zeit (in German). dpa. 29 April 2021. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "Kickoff into a new era – Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "Neue Direktorin für das Senckenberg Naturmuseum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (in German). 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Herbarium Senckenbergianum". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 27 January 2022. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Division Palaeontology and Historical Geology". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 23 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b Sachs, Sven (2001). "Diplodocus – Ein Sauropode aus dem Oberen Jura (Morrison-Formation) Nordamerikas". Natur und Museum. 131: 133–150.

- ^ a b c "Dinosaurier machen Schule, 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Nieuwland, Ilja (11 May 2017). The Colossal Stranger: A Cultural History of Diplodocus carnegii, 1902-1913 (PhD thesis). University of Groningen. ISBN 978-90-367-9728-3. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Radgen, Julia (17 January 2017). "Senckenberg-Gesellschaft feiert 200 Jahre". op-online.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Nieuwland, Ilja (2010). "The colossal stranger. Andrew Carnegie and Diplodocus intrude European Culture, 1904–1912". Endeavour. 34 (2). Elsevier BV: 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2010.04.001. ISSN 0160-9327. PMID 20537707.

- ^ a b c Mayr, Gerald; Peters, Stefan; Plodowski, Gerhard; Vogel, Olaf (1 August 2002). "Bristle-like integumentary structures at the tail of the horned dinosaur Psittacosaurus". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (8). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 361–365. Bibcode:2002NW.....89..361M. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0339-6. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 12435037. S2CID 17781405.

- ^ a b c Bell, Phil R.; Hendrickx, Christophe; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Mayr, Gerald (12 August 2022). "The exquisitely preserved integument of Psittacosaurus and the scaly skin of ceratopsian dinosaurs". Communications Biology. 5 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 809. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03749-3. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 9374759. PMID 35962036.

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Nicholls, Robert; Lautenschlager, Stephan; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Rayfield, Emily; Mayr, Gerald; Cuthill, Innes C. (2016). "3D Camouflage in an Ornithischian Dinosaur". Current Biology. 26 (18). Elsevier BV: 2456–2462. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.2456V. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.065. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 5049543. PMID 27641767.

- ^ Greshko, Michael (11 July 2023). "A dinosaur 'belly button'? This 130 million-year-old fossil reveals that—and more". Premium. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Dalton, Rex (2001). "Wandering Chinese fossil turns up at museum". Nature. 414 (6864). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 571. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..571D. doi:10.1038/414571a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11740516. S2CID 161099010.

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Nicholls, Robert; Kelly, Diane A. (2021). "A cloacal opening in a non-avian dinosaur". Current Biology. 31 (4). Elsevier BV: R182 – R183. Bibcode:2021CBio...31.R182V. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.039. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 33472049. S2CID 231644183.

- ^ "Paleontologists Reconstruct Cloacal Opening of Non-Avian Dinosaur - Paleontology". Sci.News: Breaking Science News. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Finally in 3-D: A Dinosaur's All-Purpose Orifice". The New York Times. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Lamm, Lisa (5 July 2022). "Erstmals Bauchnabel in Dino-Fossil gefunden". National Geographic (in German). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Patalong, Frank (15 September 2016). "Forscher rekonstruieren Psittacosaurus". Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Panciroli, Elsa (14 September 2016). "Scientists reveal most accurate depiction of a dinosaur ever created". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Uhl, Dieter (14 April 2020). "A reappraisal of the "stomach" contents of the Edmontosaurus annectens mummy at the Senckenberg Naturmuseum in Frankfurt/Main (Germany)". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften. 171 (1). Schweizerbart: 71–85. doi:10.1127/zdgg/2020/0224. ISSN 1860-1804. S2CID 216385262.

- ^ Glasa, Stephanie; Geographic, National; Naturmuseum, Senckenberg (20 August 2019). "Edmontosaurus-Steckbrief: Das Leben der Mumie Edmond". National Geographic (in German). Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Die Edmontosaurus-Mumie". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 7 September 2022. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, R.M.; Lucas, S.G.; Spielmann, J.A. (2011). Fossil Record 3: Bulletin 53. Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Uhl, Dieter; Havlik, Philipe (2021). "Edmonds Urzeit". Biologie in unserer Zeit (in German). 51 (3): 238–245. doi:10.11576/BIUZ-4573. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

Bereits im Jahr davor hatten die Sternbergs in derselben Gegend zwei Triceratops-Schädel entdeckt, die sie später an Senckenberg verkauften.

[Already in the year beforehand in the same area, the Sternbergs had discovered two Triceratops skulls, which they later sold to Senckenberg.] - ^ Sternberg, Charles H. (23 December 1912). "Expeditions to the Miocene of Wyoming and the Chalk Beds of Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 25: 45–49. doi:10.2307/3624243. ISSN 0022-8443. JSTOR 3624243.

- ^ "Dinosaurier · Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt (in German). 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Hessen: Neue Modelle für das Senckenberg-Museum: So sah das angebliche Dino-Monster Velociraptor wirklich aus". tagesschau.de (in German). 23 September 2024. Archived from the original on 23 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Dodo · Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt. 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Electronic inventory of European bird collections : The Natural History Museum". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ a b "FFM Ornithology: Collection". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 28 October 2019. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ ""Operation Anakonda" dauert länger: Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt ruft zu Spenden auf". hessenschau.de (in German). 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Section Herpetology". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Grube Messel und Senckenbergmuseum". main-echo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Messel Pit Fossil Site". UNESCO World Heritage. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "25 Jahre UNESCO-Welterbe Grube Messel". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "SENCKENBERG world of biodiversity | Museums | Museum Frankfurt | The Museum | Exhibitions | World natural heritage". Senckenberg.de. 20 December 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Franzen, Jens Lorenz; Brown, Kirsten M. (2010). The rise of horses : 55 million years of evolution. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9373-5. OCLC 298538023.

- ^ Franzen, Jens Lorenz; Aurich, Christine; Habersetzer, Jörg (7 October 2015). "Description of a Well Preserved Fetus of the European Eocene Equoid Eurohippus messelensis". PLOS ONE. 10 (10). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0137985. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1037985F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137985. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4622040. PMID 26445456.

- ^ Baier, Tina (7 October 2015). "Urpferd mit Fohlen". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (7 November 2014). "47-Million-Year-Old Pregnant Mare Sheds Light on Ancient Horses". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Smith, Krister T.; Schaal, Stephan; Habersetzer, Jörg; Herlyn, Hendrik G.; Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (2018). Messel : an ancient greenhouse ecosystem. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart'sche. ISBN 978-3-510-61411-0. OCLC 1054359916.

- ^ "Natur Museum Senckenberg, Frankfurt, Germany". The Quagga Project. 30 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Welchen Wert hat die Natur?". Leibniz-Magazin (in German). 27 October 2020. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "FFM: Mammalogy: Collection". Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. 30 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Lucy's Story". Institute of Human Origins. 24 November 1974. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Human evolution · Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt". Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt. 1 April 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Natur-Museum und Forschungs-Institut Senckenberg (1972). Senckenberg Natural History Museum of the Senckenberg Natural History Research Society : [guide-book]. Frankfurt am Main: Kramer. ISBN 978-3-7829-1039-2. OCLC 1256488478.

- Ziegler, Willi (1987). Naturmuseum Senckenberg Führer durch d. Ausstellungen (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Kramer. ISBN 978-3-7829-1108-5. OCLC 74831798.

- Senckenberg. Naturforschende Ges., Frankfurt a. Main (1972). Natur-Museum Senckenberg (in German). Frankfurt (am Main): Kramer. ISBN 978-3-7829-1040-8. OCLC 74134133.

- Stillbauer, Thomas (29 April 2021). "Frankfurt: Senckenberg wächst enorm". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Das neue Senckenberg: Mehr Platz für die großen Fragen". Süddeutsche.de (in German). 29 April 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "150 Jahre Senckenbergische Naturforschende Gesellschaft in Frankfurt, 28. Oktober 1967". Zeitgeschichte in Hessen (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- Scholz, Joachim; Afshar, Karin (2017). Briefe an die Lebenden Geschichten aus dem Senckenberg-Museum (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung. ISBN 978-3-929907-93-3. OCLC 986511315.

- Baumann, Margret; Bauer, Friederike; Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (2020). 200 Jahre Senckenberg. Die Zeit von 1993–2017 (in German). Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Nägele und Obermiller. ISBN 978-3-510-61416-5. OCLC 1192503441.

- Kühl, Stefan; Müller, Vera; Wolff, Birgitta. "Museum für Dodo, Dinos und Menschheits-Fragen". Forschung & Lehre (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Vor 200 Jahren gegründet: Die Senckenbergische Naturforschende Gesellschaft – Mit Bürgersinn der Natur auf der Spur". Deutschlandfunk (in German). 22 November 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- Mosbrugger, Volker; Dürr, Sören; Havlik, Philipe; Herkner, Bernd; Moll, Valentina; Neitscher, Eva; Rossmanith, Eva, eds. (2015). Auge in Auge mit der Natur Senckenberg Naturmuseum Frankfurt (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung. ISBN 978-3-929907-90-2. OCLC 926153922.

- Nigge, Klaus; Schulze-Hagen, Karl; Fiebig, Jürgen; Vogel, Johannes (2022). Vogelwelten : Expeditionen ins Museum (in German). München: Knesebeck GmbH et Co. Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-95728-410-5. OCLC 1350778543.

- Patalong, Frank (5 February 2020). "So wird ein Dino zusammengesetzt". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Blick hinter die Kulissen der Messel-Forschung". Der Spiegel (in German). 30 September 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- Seidler, Christoph (1 June 2020). "Neue Ausstellung: Paläontologen graben in Frankfurt nach Dinos". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Diplodocus, Clipping from The Morning Post". Newspapers.com. 18 May 1908. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in German and English)

- "Senckenberg Naturmuseum". Museumsufer Frankfurt. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- "Senckenberg Nature Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Das neue Senckenberg-Museum erklärt on YouTube (in German)

- Naturmuseum Senckenberg's channel on YouTube