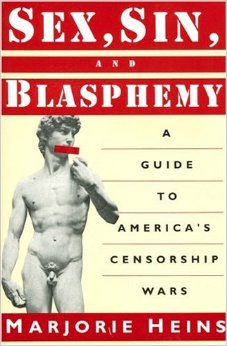

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy | |

| Author | Marjorie Heins |

|---|---|

| Original title | Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Censorship |

| Published | 1993 |

| Publisher | The New Press |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 240 |

| ISBN | 978-1-56584-048-5 |

| OCLC | 27684873 |

| Preceded by | Cutting the Mustard: Affirmative Action and the Nature of Excellence |

| Followed by | Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency," Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth |

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars is a non-fiction book by lawyer and civil libertarian Marjorie Heins that is about freedom of speech and the censorship of works of art in the early 1990s by the U.S. government. The book was published in 1993 by The New Press. Heins provides an overview of the history of censorship, including the 1873 Comstock laws, and then moves on to more topical case studies of attempts at suppression of free expression.

The book argues that artists have been scapegoated by those advocating censorship, as a method of deflecting debate away from the suppression of human rights. The author asserts that censorship of works deemed obscene has been used as a tactic throughout history to suppress women's rights. Heins argues that even if the perceived negative impacts of pornography, hip hop music, and violent films were factually accurate (and she asserts they are not), the ends would not justify the means of degrading the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. She emphasizes that education should be used to help guard against potentially dangerous notions, instead of censorship and suppression of dissent.

Background[edit]

Marjorie Heins is an attorney with a focus on civil liberties.[1] She received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Cornell University in 1967.[1] Heins graduated from Harvard Law School with a magna cum laude distinction, receiving her juris doctor degree in 1978.[1] At the time of the book's publication in 1993, Heins served as the founding director and chief lawyer for the Arts Censorship Project.[2] The project was formed as a division of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1991 during societal conflict in the U.S. over attempts to decrease financing for the National Endowment for the Arts, and to censor the musicians 2 Live Crew.[2][3] In 2000, Heins became the founding director of the Free Expression Policy Project at the National Coalition Against Censorship.[4]

Her published books prior to Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy include: Strictly Ghetto Property: The Story of Los Siete de la Raza (1972),[5][6] and Cutting the Mustard: Affirmative Action and the Nature of Excellence (1987).[7][8] Subsequent to the publication of Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy, Heins wrote Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency," Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth in 2001,[9][10] which received the 2002 Eli M. Oboler Award from the American Library Association;[11][12][13][14] and Priests of Our Democracy: The Supreme Court, Academic Freedom, and the Anti-Communist Purge in 2013,[15] which received the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Award.[16][17][18]

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars was first published in 1993 by The New Press.[19][20] The book was re-published by The New Press in 1998.[21][22]

It's stated that in September 1993, "Heins was the featured speaker at two events at the fifth annual Uncensored Celebration, sponsored by the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Oregon, where she spoke about her book and her work for the Arts Censorship Project".[23] She was a special guest at the Free Speech Lunch on September 18, 1993, as part of the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association's Trade Show Northwest.[24] On October 6, 1993, the Newark, New Jersey art gallery Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art held a reception in honor of Heins' work where she spoke about her book and her efforts to defend works of art from censorship.[25]

Content summary[edit]

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy provides the reader with a history of censorship of artworks.[3] The book argues that artists have been scapegoated by those advocating censorship, as a method of diverting debate away from the suppression of human rights.[3] The author asserts that censorship of works deemed obscene has been used as a tactic throughout history to suppress women's rights.[3] Heins describes for the reader the history of the 1873 Comstock laws.[26] It's stated that,"such laws were put forth by United States Postal Inspection Service inspector Anthony Comstock, and after he helped influence passage of the legislation, they enabled the government to criminalize sending perceived immoral writings through the mail".[27]

The book discusses the history of the division of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) that assigns movie ratings, the Classification and Rating Administration. Heins quotes New York Supreme Court Judge Charles Ramos, who observed that film directors have since learned to style their movies in such a way as to receive certain ratings from the MPAA.[28] The book focuses on the negative and political impacts of censorship. Censorship can be confusing, and many seem to not know what it is, or why it is used. Censorship is defined as "The suppression or prohibition of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security." (English Oxford Living Dictionaries).[29] Censorship, the suppression of words, images, or ideas that are "offensive," happens whenever one or more people succeed in imposing their personal political or moral values on others." (ACLU) This article points to the importance of the First Amendment rights when, particular with regards to government involvement. "Censorship can be carried out by the government as well as private pressure groups. Censorship by the government is unconstitutional." (ACLU)[30] Censorship has, to many people, gotten out of hand, and takes away from our First Amendment right of Freedom of Speech. "The question, therefore, is not whether we ought to have constraints on speech but what kinds of constraints?" (Huffpost).[31] An argument of constraints is just an argument in itself. Peoples' views on constraints can vary from personal opinions, to personal exposures and experiences. The book focuses on fear being the tool for censorship. The second principle is that expression may be restricted only if it will clearly cause direct and imminent harm to an important societal interest. The classic example is falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater and causing a stampede. "Even then, the speech may be silenced or punished only if there is no other way to avert the harm" (ACLU).[30]

Heins recounts how the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) advocated for its associated organizations to add Parental Advisory warnings on labels of music albums as a way to advise parents about possible offensive content. She describes how the Parents Music Resource Center, co-founded by Tipper Gore, and hearings held by the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee, which included Senator Al Gore, led to attempts at censorship by lawmakers in eight individual states. Heins suggests that this subsequently led to the industry's self-regulation, which the author sees as self-censorship, and blacklisting of certain albums by music stores.[28]

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy provides the reader with what the author (and many others) consider case studies of censorship in the U.S., including a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States against naked erotic dancing, laws against pornography in the 1980s supported by proponents Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin, and attempts by the Meese Commission to discourage proprietors from selling Penthouse and Playboy magazines.[28]

Formally known as the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography, it was colloquially called the Meese Report, because the people on the Commission were selected by then-Attorney General of the United States Edwin Meese.[32] Released in 1986, the Meese Report demanded U.S. citizens protest pornography because of its asserted harmful impact to women and children.[32] It is docummented "The book criticizes controversy generated by politicians against the National Endowment for the Arts, over the organization's support of photography by Robert Mapplethorpe and the work, "Piss Christ", by Andres Serrano.[26]

Heins argues that even if the perceived negative impacts of pornography, hip hop music, and violent films were factually accurate (and she asserts they are not), the ends would not justify the means of degrading the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[28] She emphasizes that education should be used to help guard against potentially dangerous notions, instead of censorship and suppression of dissent.[33] The author concludes, "A free society is based on the principle that [individuals have] a right to decide on what art or entertainment (they want) to receive – or create."[28]

Reception[edit]

Women's Review of Books commented, "Heins writes with intelligence, clarity, humor and refusal of cant. She is especially skilled at explaining legal concepts, reminding us of the elegance of a good legal argument."[34] The review found that by focusing on lawsuits and court battles, the book was lacking in individual stories and people central to the censorship fights.[34] The News & Observer wrote, "The book is as much a call to action as it is a catalog of repression."[3] In its review of the book, the San Francisco Chronicle emphasized that readers should pay attention to the author's warnings about the dangers of censorship.[28]

The Gazette observed, "Throughout the book, whether discussing attempts to censor rap music or pornography, Heins attempts to communicate the radical differences between the limits of American law and America's seemingly endless social problems. She concludes that they do not and cannot mix. The best defense, it would seem, to any form of speech that offends, is a good offense: more speech, not restrictive and oppressive laws and pressures."[26] American Book Review was critical, writing: "Overall, Heins's guide to the censorship wars is biased and woefully superficial ... I do not find her arguments for free-speech absolutism either logically or legally compelling."[35] The review concluded, "There may be good reasons for tolerating the public display of gross and disgusting art, but the First Amendment itself does not provide one."[35]

See also[edit]

- Censorship in the United States

- Film censorship in the United States

- Freedom of speech in the United States

- Freedom of the press

- Think of the children

- United States obscenity law

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Marjorie Heins Bio". The Free Expression Policy Project. fepproject.org. 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Turegano, Preston (June 8, 1993). "Arts censorship foe paints Clinton, Bush with the same brush". The San Diego Union-Tribune. p. A-8.

- ^ a b c d e Twardy, Chuck (May 31, 1993). "Fighting the foes of free speech – When it comes to arts censorship education is – just as important as litigation". The News & Observer. The News & Observer Pub. Co. p. C1.

- ^ Gaetano, Chris (July 9, 2004). "Analysis: FCC rekindles focus on indecency". UPI Perspectives. United Press International.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (1972). Strictly Ghetto Property: The Story of Los Siete de la Raza. Ramparts Press. ISBN 978-0-87867-010-9.

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Strictly Ghetto Property: The Story of Los Siete de la Raza". WorldCat. OCLC 554280.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (1987). Cutting the Mustard: Affirmative Action and the Nature of Excellence. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-12974-4.

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Cutting the Mustard: Affirmative Action and the Nature of Excellence". WorldCat. OCLC 15653313.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (2001). Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency", Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth. Hill & Wang. ISBN 978-0-374-17545-0.

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency," Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth". WorldCat. OCLC 45080058.

- ^ "Civil liberties lawyer Marjorie Heins will deliver U-M lecture on academic and intellectual freedom". State News Service. October 8, 2013 – via InfoTrac.

- ^ "Indecency fine zips lips on TV programs". The Palm Beach Post. June 13, 2006. p. 8D; Section: Business News.

Her previous book, "Not in Front of the Children: 'Indecency,' Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth," won the American Library Association's Eli Oboler Award for Best Published Work on Intellectual Freedom in 2002

- ^ "Winners". Eli M. Oboler Memorial Award. American Library Association. 2014. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ "The Eli M. Oboler Memorial Award". Eli M. Oboler Library. Idaho State University. 2014. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

The Eli M. Oboler Memorial Award is sponsored by the Intellectual Freedom Round Table (IFRT) of the American Library Association. The biennial award ... is presented for the 'best published work in the area of intellectual freedom.'

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Priests of Our Democracy: The Supreme Court, Academic Freedom, and the Anti-Communist Purge". WorldCat. OCLC 794040387.

- ^ "Winners Announced for 2013 Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Awards". The Wall Street Journal. Business Wire 2013. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. May 15, 2013. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Winners and Judges of the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Awards". Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Awards. HMH Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ "Marjorie Heins wins 2013 Hugh Hefner First Amendment Award!". From the Square. NYU Press. May 15, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (1993). Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars. The New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-048-5.

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars". WorldCat. OCLC 27684873.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (1998). Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars. The New Press. ISBN 978-0-613-91394-2.

- ^ Online Computer Library Center (2014). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars". WorldCat. OCLC 493583545.

- ^ Pintarich, Paul (September 3, 1993). "Uncensored celebration goes for the gusto". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Oregonian Publishing Co. p. AE30.

- ^ Pintarich, Paul (September 17, 1993). "Booksellers trade show opens Saturday". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Oregonian Publishing Co. p. B06.

- ^ "Reception to honor attorney with ACLU". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. October 4, 1993.

- ^ a b c Greto, Victor (July 4, 1993). "Amendment under microscope – Issue of censorship forces closer look at intent". The Gazette. Colorado Springs, Colorado. p. 4.

- ^ Massing, Michael (August 25, 2001). "Children and the demons of pop culture". The New York Times. p. B9.

- ^ a b c d e f Holt, Patricia (July 4, 1993). "Protection or Censorship?". San Francisco Chronicle. p. 2; Section: Sunday Review.

- ^ "censorship - Definition of censorship in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b "What Is Censorship?".

- ^ Forum, The University of Central Florida (9 March 2016). "Censorship Is Not All Bad". HuffPost.

- ^ a b Martin Merzer; Itabari Njeri (September 25, 1986). "Censorship on rising tide across U.S.A. words and thoughts under greater attack". The Miami Herald. Florida. p. 1A.

- ^ Rivenburg, Roy (June 7, 1997). "T is for Trouble where smutty T-shirts are concerned". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Star-Telegram, Inc. Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b Levinson, Nan (April 1994). "Book Review: Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". Women's Review of Books. 11: 1. doi:10.2307/4021815. ISSN 0738-1433. JSTOR 4021815.

- ^ a b Trout, Paul A. (October–November 1994). "Book Review: Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". American Book Review. 16: 28. ISSN 0149-9408.

Further reading[edit]

- Curtis, Michael Kent (2000). Free Speech, "The People's Darling Privilege": Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2529-2.

- Fairman, Christopher M. (2009). Fuck: Word Taboo and Protecting Our First Amendment Liberties. Sphinx Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57248-711-6.

- Godwin, Mike (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-57168-4.

- Lewis, Anthony (2007). Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03917-3.

- Kembrew McLeod; Lawrence Lessig (foreword) (2007). Freedom of Expression: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5031-6.

- Nelson, Samuel P. (2005). Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8173-0.

- Book reviews

- Buck, Richard M. (January 1994). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom. 43: 9–10. ISSN 0028-9485.

- Greenberg, Cory (1993). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". New York University Review of Law & Social Change. 20: 684–686. ISSN 0048-7481.

- Kalman, Judy Zeprun (September 1996). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". Massachusetts Law Review. 81: 136–137. ISSN 0163-1411.

- Karlin, Oliver (December 1993 – January 1994). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". SIECUS Report. 22: 25–26. ISSN 0091-3995.

- Riddell, Jennifer L. (October 1994). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". New Art Examiner. 22: 52–53. ISSN 0886-8115.

- Sennett, Richard (July 1994). "Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy". Contemporary Sociology. 23: 487. doi:10.2307/2076349. ISSN 0094-3061. JSTOR 2076349.

External links[edit]