Siston

| Siston | |

|---|---|

St. Anne's Church, Siston, viewed from the southeast | |

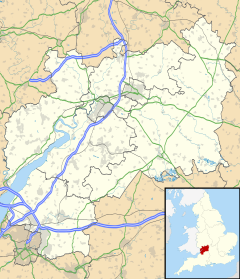

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 4,552 (parish, 2011)[1] |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Bristol |

| Postcode district | BS15, BS16, BS30 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Siston (pronounced "sizeton")[2] is a small village in South Gloucestershire, England. It is 7 miles (11 km) east of Bristol at the confluence of the two sources of the Siston Brook, a tributary of the River Avon. The village consists of a number of cottages and farms centred on St Anne's Church, and the grand Tudor manor house of Siston Court. Anciently it was bordered to the west by the royal Hunting Forest of Kingswood, stretching westward most of the way to Bristol Castle, always a royal possession, caput of the Forest. The local part of the disafforested Kingswood became Siston Common but has recently been eroded by the construction of the Avon Ring Road and housing developments. In 1989 the village and environs were classed as a conservation area and thus have statutory protection from overdevelopment.

History

[edit]At the time of the Roman conquest the area was woodland, but there is evidence of Roman remains. It has been known throughout time as Sistone, Siston, Systun, Syton, and Sytone. The name may derive from "Size-town" or may have been derived from the Saxon "Sige's Farmstead".[3] In 1273 the occupants used Marchling[clarification needed] as part of their agricultural practices; at that time marl was reportedly spread on two carucates of land.[4] The Domesday Book of 1086 records Siston as belonging to a Norman knight, Roger de Berkeley, who owned Berkeley Castle, and lands from Gloucester in the north to Bristol in the south.[5] The manor of Siston lay in the Hundred of Pucklechurch, Gloucestershire, and adjoined the Royal Forest of Kingswood to the west, and claimed right of purlieu over a portion of it.[6] It was subsequently held by the families of Walerand, Plokenet, Corbet, Denys, Billingsley, Trotman and Rawlins.

Governance

[edit]Siston is an electoral ward, with some additional areas; the total ward population taken at the 2011 census was 4,809.[7]

Siston Court

[edit]

Siston Court is a grade I listed Elizabethan manor house,[8][9] built by Sir Maurice Denys (1516–1563).[10][11] It is situated on a ridge overlooking the Siston Brook Valley[8] and was constructed on the site of a previous medieval mansion of the Denys family. The building is U-shaped with two wings flanking a courtyard.[12] In 1607 when owned by Mr. Weekes who had purchased Siston Court from the Denys family, it was recorded as:[13] "a new house of stone which cost £3,000 built by Dennis; a park which will keep 1,000 fallow deer & rich mines of coal which yield almost as great revenue as the land"[14][15] In 1710, during the Trotman period of ownership, the Britannia Illustrata published an engraving by Jan Kip (1653–1722) of the house showing it surrounded by extensive formal landscaped gardens. In the following century landscaping resulted in a park-like setting with a more natural garden. The architect Sanderson Miller, husband of Susannah Trotman, daughter of Samuel Trotman of Siston Court, may have influenced the creation of informal gardens.[8][16][nb 1]

The 18th century "pepper-pot" lodges and 19th century "The Grange", once a home to the nurseryman, may have been influenced by Miller, whose style included the "ogee-shaped roofs and door heads and Gothic Revival windows alternating with cross-loops."[19][nb 2]

The pair of now empty niches on the internal facades of the wings are similar to the niches on the facade of Montacute House, Somerset,[21] which contain statues of the Nine Worthies, dressed as Roman soldiers, Italian Renaissance in inspiration.[22]

Houses were built locally for estate workers at Siston Court in the 18th and 19th century. During the 20th century the estate was subdivided, and farm land was converted to woodland by the Forestry Enterprise or for pony paddocks.[8][nb 3] The ornate Renaissance Tudor chimneypiece in the great hall was purchased by Emperor Haile Selasse, then in exile in Bristol, who shipped it to Addis-Ababa Palace.[23][nb 4] Siston Court still retains much of the character of the 16th-century manor house and its original Elizabethan façade.[12][nb 5] In the middle of the 20th century the manor was subdivided into flats.[9]

Queen Anne of Denmark, wife of King James I, stayed at Siston Court in June 1613 as guest of Sir Henry Billingsley.[26][27] She had been lavishly entertained by the Corporation of Bristol during the day, with massive military displays and mock sea battles between Turk and English mariners having been staged for her, immortalised in a versified account by Naile, an apprentice.[27] According to a Siston Court servant, she stayed in the "room upstairs called 'the Queen's Chamber'".[28]

The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, visited the Court as guest of the Rawlins family.[29]

Mounts Court, demolished in 1922, was another important local mansion house.[30]

Sir Maurice Denys's patron was thought to have been Admiral Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley the ambitious and reckless younger brother of Protector Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, brother of Queen Jane Seymour and uncle of King Edward VI. Having been refused as a spouse by Princess Elizabeth, he was determined to wed the ex-Queen Katherine Parr, even before a nine-month delay, considered by courtiers to have been seemly and constitutionally prudent, had expired. It may have been as a result of Denys's complicity in these arrangements that Katherine, widowed by King Henry VIII in 1547, resided for eight weeks of her future short life in a house within the vicinity of Siston, known as Mount's Court, held by the Strange family.[31][32]

On 23 October 1989, the area was designated as the "Siston Conservation Area" to protect historical sites such as Siston Court and its buildings, and the hamlet of Siston, including St Anne's Church and historic farms, cottages and open fields.[3]

Church buildings

[edit]

St Anne's Church, located between Siston Court and the village of Siston, is at the edge of open fields and has scenic views of the countryside.[33] The original Norman church was built of rubble in the mid-12th century.[34][33] It was rebuilt and expanded in the 13th century and from the 17th to the 20th centuries.[34][33] It has a west tower and a gabled south porch, with a small chapel protruding from the south wall. A tree of life is sculpted on the Norman tympanum of the south doorway. Marks on the oak door are said to be bullet holes from Cromwell's troops who used the church as stables on the way to the Battle of Lansdowne in 1642.[35] The most important feature of the interior is a 12th-century lead baptismal font. Many of the features and furnishings in the interior date from the 17th to 19th centuries.[34] South of the church is the formal Georgian rectory. According to an 1839 tithe map, the church had a formal garden, now the site of the church hall.[33]

The 12th-century baptismal font is of lead,[34] unusual in England.[36][nb 6] The Siston font displays six figures, three of which seem to be of Christ, as a nimbus is shown. The other three may be some of the Four Evangelists, who hold their own gospels and bless with two fingers of their right hands. It appears that the prototype of this font, as the finer versions show, had twelve figures, possibly the Twelve Apostles. There are twelve niches shown on the Siston font, but six are filled with acanthus scroll-work.[36]

In the 1900s, Mrs. Rawlins, wife of the owner of Siston Court, made a large wall-painting[37] in the Pre-Raphaelite-style of Edward Burne-Jones for church covering the chancel arch,[38][39] based upon a Renaissance fresco in the Palazzo Riccardi in Florence.[39][40] Daughters of Mrs. Rawlins were models for some of the angels in the painting.[38][39]

Although the manor historically was held from the Bishop of Bath and Wells, the parish church fell within the Diocese of Worcester. The advowson was held by the lords of the manor of Siston until 1937, when it was donated in perpetuity by J E Rawlins of Siston Court to the Bishop of Bristol.[41]

The Church of St Barnabas, a grade II listed building, was built by James Park Harrison in 1849. The decorated style building is made of rubble with a west tower and broach spire.[42]

The Methodist Ebeneezer Chapel was built in 1810 of rendered walling with stone coping.[43]

Suggest : archaeological dig underway. needs information.

Siston Common

[edit]Siston Common, or "the Commons", is an area that runs across the width of the parish with bridleways and footpaths. Historically it was used by local farmers for the grazing of cattle, goats, horses, ducks and chickens.[44] The Avon Ring Road has been built on the western edge of the common/

Siston Parish Council

[edit]The members of Siston Parish Council serve voluntarily and are unpaid. They serve a term of four years. They meet on the 3rd Thursday of each month in the Warmley Community Centre to manage affairs related to Siston, such as bus shelters, local planning, and rural footpaths.[45]

Notable residents

[edit]- Corbet family

- Alfred Davidson

- Denys family of Siston

- Billingsley family

- Maurice Denys

- Gilbert Denys

- John Clark Monks

- Robert Walerand

- Sir Aubrey Trotman-Dickenson

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dickins and Stanton claimed that Susanna's father was Samuel.[17]

- ^ Miller drafted plans on the back of a letter for a "Poor's House" inscribed "Siston, Nov.21 1759". Hester Miller, his daughter, married Siston Court resident, Fiennes Trotman.[16][20]

- ^ The style also reflected the landscaping styles of William Kent and Capability Brown.[8]

- ^ John Harris, in his book Moving Rooms, states that the hall chimney was removed by Charles Angell in 1936.[24]

- ^ An image of an interior from 1930 can be seen in W.J. Robinson's "Siston Court" showing Oliver Cromwell's cavalry jack boots, left behind by him.[25]

- ^ Only about 38 leaden fonts survive in England, nine of which are in Gloucestershire, the greatest number in any county.[36] Other similar fonts exist in the Lady Chapel of Gloucester Cathedral (given to the cathedral in 1940, originally from St. James's Church, Lancaut, Glos., now ruined); at Frampton-on-Severn; Rendcomb-St-Peter and at Dorchester Abbey.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ "parish population 2011". Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Anciently Syston, Sistone, Syton, Sytone and Systun etc.

- ^ a b Siston Conservation Area. South Glouchestershire Council. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ H. E. Hallam; Joan Thirsk; H. P. R. Finberg. (1988). The Agrarian history of England and Wales: 1042–1350. Edited by H.E. Hallam. Cambridge University Press. p. 378. Retrieved 9 July 2013. ISBN 978-0-521-20073-8.

- ^ Siston Domesday Online. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Cecil Papers: May 1609 Vol 24. 6/5/1609". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Ward population 2011". Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Siston Conservation Document – Supplementary Planning Document. South Glouchester Council. pp. 2, 4, 5, 7.

- ^ a b Siston Court. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Bindoff, S.T. (1982). The House of Commons 1509–1558. London. 2. pp. 31–33

- ^ Cecil Papers: Miscellaneous 1607, Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House, 16–30, Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. 19: (1965) [1607], pp. 433 (124.72) Retrieved 8 July 2013. Name spelled Sir Morris Dennis.

- ^ a b Siston Conservation Document – Supplementary Planning Document. South Glouchester Council. p. 10.

- ^ Cecil Papers. vol 19, p.433. (124.72)

- ^ Cecil Papers at Hatfield House, CP19/433, CP124/72

- ^ Weeks offered the sale of the manor to the Earl of Salisbury, who was reported to not have received the offer letters Cecil Papers: December 1607, 1–15, Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. 19: (1965) [1607], p.374 (123.113) Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b John Burke (1836). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Enjoying Territorial Possessions Or High Official Rank: But Uninvested with Heritable Honours. Henry Colburn. p. 699. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Lilian Dickins; Mary Stanton (1910). An eighteenth-century correspondence: being the letters of Deane Swift—Pitt—The Lytteltons and the Granvilles—Lord Dacre—Robert Nugent—Charles Jenkinson—the Earls of Guilford, Coventry, & Hardwicke—Sir Edward Turner—Mr. Talbot of Lacock, and others to Sanderson Miller, esq., of Radway. Duffield. p. 123. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Historic England. "Lodges to Siston Court (Grade II*) (1231513)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Siston Conservation Document – Supplementary Planning Document. South Glouchester Council. p. 9-10.

- ^ Hawkes, H.W. Dissertation on the Architectural Work of Sanderson Miller of Radway. 1964. p. 75.

- ^ Nicolson, Nigel. (1978). National Trust Book of Great Houses. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 71–73. ISBN 0-297-77411-5

- ^ Nicolson, Nigel (1965) Great houses of Britain. Hamlyn Publishing Group ISBN 0-586-05604-1

- ^ Brooke, Gerry. (11 November 2003). A Manor with Many Owners. Bristol Evening Post.

- ^ John Harris (2007). Moving Rooms. Yale University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-300-12420-0. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Robinson, William James. (1930). "Siston Court". West Country Manors. Bristol: St. Stephen's Press. p. 168.

- ^ Mark Cartwright Pilkinton (1997). Bristol. University of Toronto Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8020-4221-7. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b Asams, William (1625). Chronicle of Bristol.

- ^ David Rollison (29 October 1992). The Local Origins of Modern Society: Gloucestershire 1500–1800. Taylor & Francis. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-203-99149-7. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Rourke, Elana. (2010). Siston Court Remembered Pucklechurch.

- ^ "Warmley & Siston - One Hundred years of history - Part 2 of 7 - 1914 - 1930". Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Rudge, Thomas (1803). The History of the County of Gloucester (Volume 2). General Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-1152300392.

- ^ Robinson, W.J. (1930). "Siston Court". West Country Manors. Bristol. p.169.

- ^ a b c d Siston Conservation Document – Supplementary Planning Document. South Glouchester Council. pp. 5, 12.

- ^ a b c d "Parish Church of St. Anne, Siston". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Webb, Mary & Gardner, Pamela, The History of St Anne's Church Syston, August 2008

- ^ a b c d Webb, Mary; Gardner, Pamela (2008). The History of St Anne's Church Syston. p. 6.

- ^ Actually on paper affixed to the chancel arch

- ^ a b St Anne, Syston. Church of England. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Bryant, Alan. Life in Siston and Warmley 1894–1994 Siston Parish Council. Retrieved. 8 July 2013.

- ^ Arthur Mee (1938). Gloucestershire: the glory of the Cotswolds. Hodder and Stoughton, limited. p. 356. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "No. 34373". The London Gazette. 19 February 1937. p. 1170.

- ^ Church of St Barnabas. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Ebeneezer Chapel. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ News – The Commons. Siston Parish Council. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ The Role of Your Parish Council. Siston Parish Council. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Braine, A. (1891). "Siston" The history of Kingswood Forest: including all the ancient manors and villages in the neighbourhood. E. Nister. p. 184–190.

- Rourke, Elana. (2010). Siston Court Remembered Pucklechurch.

- Barbara Tuttiett; Kingswood History Society. Sixteenth century court book of Siston. Able Pub.; 1 January 2002. ISBN 978-1-903607-26-8.

External links

[edit]- Siston Court, Parks & Gardens UK

- St. Anne's Church, Rootsweb