Battleship Potemkin

| Battleship Potemkin | |

|---|---|

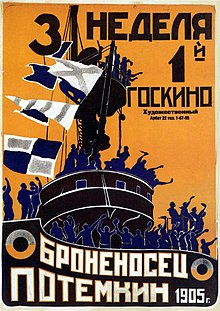

Original Soviet release poster in Russian | |

| Бронено́сец «Потёмкин» | |

| Directed by | Sergei Eisenstein |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Jacob Bliokh |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Edmund Meisel |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Goskino |

Release date |

|

Running time | 74 minutes |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Languages |

|

Battleship Potemkin (Russian: Броненосец «Потёмкин», romanized: Bronenosets «Potyomkin», [brənʲɪˈnosʲɪts pɐˈtʲɵmkʲɪn]), sometimes rendered as Battleship Potyomkin, is a 1925 Soviet silent epic film produced by Mosfilm.[1] Directed and co-written by Sergei Eisenstein, it presents a dramatization of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against their officers.

In 1958, the film was voted on Brussels 12 list at the 1958 World Expo. Battleship Potemkin is widely considered one of the greatest films of all time.[2][3][4] In the most recent Sight and Sound critics' poll in 2022, it was voted the fifty-fourth-greatest film of all time, and it had been placed in the top 10 in many previous editions.[5]

Plot

[edit]The film is set in June 1905; the protagonists of the film are the members of the crew of the Potemkin, a battleship of the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet. Eisenstein divided the plot into five acts, each with its own title:

Act I: Men and Maggots

[edit]The scene begins with two sailors, Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk, discussing the need for the crew of the Potemkin, which is anchored off the island of Tendra, to support the revolution then taking place within Russia. After their watch, they and other off-duty sailors are sleeping. As an officer inspects the quarters, he stumbles and takes out his aggression on a sleeping sailor. The ruckus causes Vakulinchuk to awake, and he gives a speech to the men as they come to. Vakulinchuk says, "Comrades! The time has come when we too must speak out. Why wait? All of Russia has risen! Are we to be the last?" The scene cuts to morning, where sailors are remarking on the poor quality of the meat. The meat appears to be rotten and covered in maggots, and the sailors say that "even a dog wouldn't eat this!" The ship's doctor, Smirnov, is called over to inspect the meat by the captain. Rather than maggots, the doctor says that they are insects, and they can be washed off before cooking. The sailors further complain about the poor quality of the rations, but the doctor declares the meat edible and ends the discussion. Senior officer Giliarovsky forces the sailors still looking over the rotten meat to leave the area, and the cook begins to prepare borscht, although he too questions the quality of the meat. The crew refuses to eat the borscht, instead choosing bread, water, and canned goods. While cleaning dishes, one of the sailors sees an inscription on a plate which reads "give us this day our daily bread". After considering the meaning of this phrase, the sailor smashes the plate and the scene ends.

Act II: Drama on the Deck

[edit]All those who refuse the meat are judged guilty of insubordination and are brought to the fore-deck where they receive religious last rites. The sailors are obliged to kneel and a canvas cover is thrown over them as a firing squad marches onto the deck. The First Officer gives the order to fire, but in response to Vakulinchuk's pleas the sailors in the firing squad lower their rifles and the uprising begins. The sailors overwhelm the outnumbered officers and take control of the ship. The officers are thrown overboard, the ship's priest is dragged out of hiding, and finally the doctor is thrown into the ocean as 'food for the worms'. The mutiny is successful but Vakulinchuk, the charismatic leader of the rebels, is killed.

Act III: A Dead Man Calls Out

[edit]The Potemkin arrives at the port of Odessa. Vakulinchuk's body is taken ashore and displayed publicly by his companions in a tent with a sign on his chest that says "For a spoonful of borscht" (Изъ-за ложки борща). The citizens of Odessa, saddened yet empowered by Vakulinchuk's sacrifice, are soon whipped into a frenzy against the Tsar and his government by sympathizers. A man allied with the government tries to turn the citizens' fury against the Jews, but he is quickly shouted down and beaten by the people. The sailors gather to make a final farewell and praise Vakulinchuk as a hero. The people of Odessa welcome the sailors, but they attract the police as they mobilize against the government.

Act IV: The Odessa Steps

[edit]The citizenry of Odessa take to their boats, sailing out to the Potemkin to support the sailors, while a crowd of others gather at the Odessa steps to witness the happenings and cheer on the rebels. Suddenly a detachment of dismounted Cossacks form battle lines at the top of the steps and march toward a crowd of unarmed civilians including women and children, and begin firing and advancing with fixed bayonets. Every now and again, the soldiers halt to fire a volley into the crowd before continuing their impersonal, machine-like assault down the stairs, ignoring the people's pleas. Meanwhile, government cavalry attack the fleeing crowd at the bottom of the steps as well, cutting down many of those who survived the dismounted assault. Brief sequences show individuals among the people fleeing or falling, a baby carriage rolling down the steps, a woman shot in the face, broken glasses, and the high boots of the soldiers moving in unison.[6]

In retaliation, the sailors of the Potemkin use the guns of the battleship to fire on the city opera house, where Tsarist military leaders are convening a meeting. Meanwhile, there is news that a squadron of loyal warships is coming to quell the revolt of the Potemkin.

Act V: One Against All

[edit]The sailors of the Potemkin decide to take the battleship out from the port of Odessa to face the fleet of the Tsar, flying the red flag along with the signal "Join us". Just when battle seems inevitable, the sailors of the Tsarist squadron refuse to open fire, cheering and shouting to show solidarity with the mutineers and allowing the Potemkin to pass between their ships.

Cast

[edit]- Aleksandr Antonov as Grigory Vakulinchuk (Bolshevik sailor)

- Vladimir Barsky as Commander Evgeny Golikov

- Grigori Aleksandrov as Chief Officer Giliarovsky

- Mikhail Gomorov as Afanasi Matushenko

- Maksim Shtraukh as Fyodor Smirnov

- Aleksandr Levshin as Petty Officer

- Ivan Bobrov as Young sailor flogged while sleeping

- Nina Poltavseva as Woman with pince-nez

- Lyrkean Makeon as the Masked Man

- Konstantin Feldman as Student agitator

- Beatrice Vitoldi as Woman with the baby carriage

Production

[edit]On the 20th anniversary of the first Russian revolution, the commemorative commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided to stage a number of performances dedicated to the revolutionary events of 1905. As part of the celebrations, it was suggested that a "... grand film [be] shown in a special program, with an oratory introduction, musical (solo and orchestral) and a dramatic accompaniment based on a specially written text".[7] Nina Agadzhanova was asked to write the script and direction of the picture was assigned to 27-year-old Sergei Eisenstein.[8]

In the original script, the film was to highlight a number of episodes from the 1905 revolution: the Russo-Japanese War, Armenian–Tatar massacres of 1905–1907, revolutionary events in St. Petersburg and the Moscow uprising. Filming was to be conducted in a number of cities within the USSR.[9]

Eisenstein hired many non-professional actors for the film; he sought people of specific types instead of famous stars.[10][9]

Shooting began on 31 March 1925. Eisenstein began filming in Leningrad and had time to shoot the railway strike episode, horsecar, city at night and the strike crackdown on Sadovaya Street. Further shooting was prevented by deteriorating weather, with fog setting in. At the same time, the director faced tight time constraints: the film needed to be finished by the end of the year, although the script was approved only on 4 June. Eisenstein decided to give up the original script consisting of eight episodes, to focus on just one, the uprising on the battleship Potemkin, which involved just a few pages (41 frames) from Agadzhanova's script. Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov essentially recycled and extended the script.[11] In addition, during the progress of making the film, some episodes were added that had existed neither in Agadzhanova's script nor in Eisenstein's scenic sketches, such as the storm scene with which the film begins. As a result, the content of the film was far removed from Agadzhanova's original script.

The film was shot in Odessa, at that time a center of film production where it was possible to find a suitable warship for shooting.

The first screening of the film took place on 21 December 1925 at a ceremonial meeting dedicated to the anniversary of the 1905 revolution at the Bolshoi Theatre.[12][13] The premiere was held in Moscow on 18 January 1926, in the 1st Goskinoteatre (now called the Khudozhestvenny).[14][15]

The silent film received a voice dubbing in 1930, was restored in 1950 (composer Nikolai Kryukov) and reissued in 1976 (composer Dmitri Shostakovich) at Mosfilm with the participation of the USSR State Film Fund and the Museum of S.M. Eisenstein under the artistic direction of Sergei Yutkevich.

In 1925, after sale of the film's negatives to Germany and reediting by director Phil Jutzi, Battleship Potemkin was released internationally in a different version from that originally intended. The attempted execution of sailors was moved from the beginning to the end of the film. Later it was subjected to censorship, and in the USSR some frames and intermediate titles were removed. The words of Leon Trotsky in the prologue were replaced with a quote from Lenin.[15] In 2005, under the overall guidance of the Foundation Deutsche Kinemathek, with the participation of the State Film Fund and the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, the author's version of the film was restored, including the music by Edmund Meisel.[16]

The battleship Kniaz Potemkin Tarritcheski, later renamed Panteleimon and then Boretz Za Svobodu, was derelict and in the process of being scrapped at the time of the film shoot. It is usually stated that the battleship Dvenadsat Apostolov was used instead, but she was a very different design of vessel from that of the Potemkin, and the film footage matches the battleship Rostislav more closely. The Rostislav had been scuttled in 1920, but her superstructure remained completely above water until 1930. Interior scenes were filmed on the cruiser Komintern. Stock footage of Potemkin was used to show her at sea, and stock footage of the French fleet depicted the waiting Russian Black Sea fleet. Anachronistic footage of triple-gun-turret Russian dreadnoughts was also included.[17][9]

In the film, the rebels raise a red flag on the battleship, but the orthochromatic black-and-white film stock of the period made the color red look black, so a white flag was used instead. Eisenstein hand-tinted the flag in red in 108 frames for the premiere at the Grand Theatre, which was greeted with thunderous applause by the Bolshevik audience.[15]

Film style and content

[edit]The film is composed of five episodes:

- "Men and Maggots" (Люди и черви), in which the sailors protest having to eat rotten meat.

- "Drama on the Deck" (Драма на тендре), in which the sailors mutiny and their leader Vakulinchuk is killed.

- "A Dead Man Calls for Justice" (Мёртвый взывает), in which Vakulinchuk's body is mourned by the people of Odessa.

- "The Odessa Steps" (Одесская лестница), in which imperial soldiers massacre the Odesans.

- "One against all" (Встреча с эскадрой), in which the squadron tasked with intercepting the Potemkin instead declines to engage; lowering their guns, its sailors cheer on the rebellious battleship and join the mutiny.

Eisenstein wrote the film as revolutionary propaganda,[18][19] but also used it to test his theories of montage.[20] The revolutionary Soviet filmmakers of the Kuleshov school of filmmaking were experimenting with the effect of film editing on audiences, and Eisenstein attempted to edit the film in such a way as to produce the greatest emotional response, so that the viewer would feel sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and hatred for their overlords. In the manner of most propaganda, the characterization is simple, so that the audience could clearly see with whom they should sympathize.

A notable example of Eisenstein's montage technique is the sequence featuring the lion statues at the Vorontsov Palace in Crimea. The statues—a sleeping lion, a waking lion, and one rising to its feet—are edited in succession to create the illusion of movement, symbolizing the revolutionary awakening. These statues were modeled after the Medici Lions of Renaissance Italy, linking classical art to the film's modern revolutionary themes.[21]

Eisenstein's experiment was a mixed success; he "was disappointed when Potemkin failed to attract masses of viewers",[22] but the film was also released in a number of international venues, where audiences responded positively. In both the Soviet Union and overseas, the film shocked audiences, but not so much for its political statements as for its use of violence, which was considered graphic by the standards of the time.[23][24][25] The film's potential to influence political thought through emotional response was noted by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, who called Potemkin "a marvelous film without equal in the cinema ... anyone who had no firm political conviction could become a Bolshevik after seeing the film."[25][26] He was even interested in getting Germans to make a similar film. Eisenstein did not like the idea and wrote an indignant letter to Goebbels in which he stated that National Socialistic realism did not have either truth or realism.[27] The film was not banned in Nazi Germany, although Heinrich Himmler issued a directive prohibiting SS members from attending screenings, as he deemed the movie inappropriate for the troops.[25] The film was eventually banned in some countries, including the United States and France for a time, as well as in its native Soviet Union. The film was banned in the United Kingdom longer than was any other film in British history.[28]

The Odessa Steps sequence

[edit]One of the most celebrated scenes in the film is the massacre of civilians on the Odessa Steps (also known as the Primorsky or Potemkin Stairs). This sequence has been assessed as a "classic"[29] and one of the most influential in the history of cinema.[30][31] In the scene, the Tsar's soldiers in their white summer tunics march down a seemingly endless flight of steps in a rhythmic, machine-like fashion, firing volleys into a crowd. A separate detachment of mounted Cossacks charges the crowd at the bottom of the stairs. The victims include an older woman wearing pince-nez, a young boy with his mother, a student in uniform and a teenage schoolgirl. A mother pushing an infant in a baby carriage falls to the ground dying and the carriage rolls down the steps amid the fleeing crowd.

The massacre on the steps, although it did not take place in daylight[32] or as portrayed,[33] was based on the fact that there were widespread riots in other parts of the city, sparked off by the arrival of the Potemkin in Odessa Harbour. Both The Times and the resident British consul reported that troops fired on the rioters; deaths were reportedly in the hundreds.[34] Roger Ebert writes, "That there was, in fact, no tsarist massacre on the Odessa Steps scarcely diminishes the power of the scene ... It is ironic that [Eisenstein] did it so well that today, the bloodshed on the Odessa steps is often referred to as if it really happened."[35]

Treatment in other works of art

[edit]

The scene is perhaps the best example of Eisenstein's theory on montage, and many films pay homage to the scene, including:

- Terry Gilliam's Brazil

- Brian De Palma's The Untouchables[36]

- George Lucas's Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith[37]

- Tibor Takacs's Deathline

- Laurel and Hardy's The Music Box

- Chandrashekhar Narvekar's Hindi film Tezaab

- Shukō Murase's anime Ergo Proxy

- Peter Sellers' The Magic Christian

- The Children Thief

- Johnnie To's Three

- Ettore Scola's We All Loved Each Other So Much

- Denis Villeneuve's Dune

Several films spoof it, including

- Woody Allen's Bananas and Love and Death

- Zucker, Abrahams, and Zucker's Naked Gun 33+1⁄3: The Final Insult (though also a parody of The Untouchables)

- the Soviet-Polish comedy Deja Vu

- Jacob Tierney's The Trotsky

- The short film Mr. Bill Goes to Washington

- The German–Turkish film Kebab Connection

- The 1999 direct-to-video film An American Tail: The Mystery of the Night Monster

- The Italian Fantozzi comedy film Il secondo tragico Fantozzi

Non-film shows that parody the scene include:

- a 1996 episode of the American adult animated sitcom, Duckman, entitled "The Longest Weekend"

- a 2014 episode of Rake (Season 3, Episode 5)

Artists and others influenced by the work include:

- The Irish-born painter Francis Bacon (1909–1992). Eisenstein's images profoundly influenced Bacon, particularly the Odessa Steps shot of the nurse's broken glasses and open-mouthed scream. The open mouth image appeared first in Bacon's Abstraction from the Human Form, in Fragment of a Crucifixion, and other works including his famous Head series.[38]

- The Soviet Union-born photographer and artist Alexey Titarenko was inspired by and paid tribute to the Odessa Steps sequence in his series City of Shadows (1991–1993), shot near the subway station in Saint Petersburg.[39]

- The popular culture periodical (and website) Odessa Steps Magazine, started in 2000, is named after the sequence.

- The 2011 October Revolution parade in Moscow featured a homage to the film.[40]

- Episode 2 of Japanese animation Ergo Proxy titled "Confessions of a Fellow Citizen".

Distribution, censorship and restoration

[edit]After its first screening, the film was not distributed in the Soviet Union and there was a danger that it would be lost among other productions. Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky intervened because his good friend, poet Nikolai Aseev, had participated in the making of the film's intertitles. Mayakovsky's opposing party was Sovkino's president Konstantin Shvedchikov. He was a politician and friend of Vladimir Lenin who once hid Lenin in his home before the Revolution. Mayakovsky presented Shvedchikov with a hard demand that the film would be distributed abroad, and intimidated Shvedchikov with the fate of becoming a villain in history books. Mayakovsky's closing sentence was "Shvedchikovs come and go, but art remains. Remember that!" Besides Mayakovsky many others also persuaded Shvedchikov to spread the film around the world and after constant pressure from Sovkino he eventually sent the film to Berlin. There Battleship Potemkin became a huge success, and the film was again screened in Moscow.[9]

When Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford visited Moscow in July 1926, they were full of praise for Battleship Potemkin; Fairbanks helped distribute the film in the U.S., and even asked Eisenstein to go to Hollywood. In the U.S. the film premiered in New York on 5 December 1926, at the Biltmore Theatre.[41][42]

The film was shown in an edited form in Germany, with some scenes of extreme violence edited out by German distributors. A written introduction by Trotsky was cut from Soviet prints after he ran afoul of Stalin. The film was banned in the United Kingdom[43][44] (until 1954; it was then X-rated[45][46] until 1987[47]), France, Japan, and other countries for its revolutionary zeal.[48]

Today the film is widely available in various DVD editions. In 2004, a three-year restoration of the film was completed. Many excised scenes of violence were restored, as well as the original written introduction by Trotsky. The previous English intertitles, which had toned down the mutinous sailors' revolutionary rhetoric, were corrected so that they would now be an accurate translation of the original Russian titles.

Posters

[edit]

The posters for the movie Battleship Potemkin created by Aleksandr Rodchenko in 1925 became prominent examples of Soviet constructivist art.[49] One version shows a sniper sight on two scenes of Eisenstein's movie, representing two guns of the Battleship.[50]

Another version was created in 1926.[51] Being part of collections of museums such as Valencia's IVAM,[52] shows a much clearer image.[52] Using a central romboid figure with the Battleship on it, combines graphic design and photomontage to create an image where the Battleship is the main protagonist.[52] The clear image contrasts with the aggressive use of painting,[53] whereas the diagonal lines are also a recognizable trait of the work.[53]

There is also a poster where the central figure is a sailor, with the Battleship on the central background.[54]

Soundtracks

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

To retain its relevance as a propaganda film for each new generation, Eisenstein hoped the score would be rewritten every 20 years. The original score was composed by Edmund Meisel. A salon orchestra performed the Berlin premiere in 1926. The instruments were flute/piccolo, trumpet, trombone, harmonium, percussion and strings without viola. Meisel wrote the score in twelve days because of the late approval of film censors. As time was so short Meisel repeated sections of the score. Composer/conductor Mark-Andreas Schlingensiepen has reorchestrated the original piano score to fit the version of the film available today.

Nikolai Kryukov composed a new score in 1950 for the 25th anniversary. In 1985, Chris Jarrett composed a solo piano accompaniment for the movie. In 1986 Eric Allaman wrote an electronic score for a showing that took place at the 1986 Berlin International Film Festival. The music was commissioned by the organizers, who wanted to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the film's German premiere. The score was played only at this premiere and has not been released on CD or DVD. Contemporary reviews were largely positive apart from negative comment because the music was electronic. Allaman also wrote an opera about Battleship Potemkin, which is musically separate from the film score.

In commercial format, on DVD for example, the film is usually accompanied by classical music added for the "50th anniversary edition" released in 1975. Three symphonies from Dmitri Shostakovich have been used, with No. 5, beginning and ending the film, being the most prominent. A version of the film offered by the Internet Archive has a soundtrack that also makes heavy use of the symphonies of Shostakovich, including his Fourth, Fifth, Eighth, Tenth, and Eleventh.

In 2007, Del Rey & The Sun Kings also recorded this soundtrack. In an attempt to make the film relevant to the 21st century, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe (of the Pet Shop Boys) composed a soundtrack in 2004 with the Dresden Symphonic Orchestra. Their soundtrack, released in 2005 as Battleship Potemkin, premiered in September 2004 at an open-air concert in Trafalgar Square, London. There were four further live performances of the work with the Dresdner Sinfoniker in Germany in September 2005, and one at the Swan Hunter shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne in 2006.

The avant-garde jazz ensemble Club Foot Orchestra has also re-scored the film, and performed live accompanying the film with a score by Richard Marriott, conducted by Deirdre McClure. For the 2005 restoration of the film, under the direction of Enno Patalas in collaboration with Anna Bohn, released on DVD and Blu-ray, the Deutsche Kinemathek - Museum fur Film und Fernsehen, commissioned a re-recording of the original Edmund Meisel score, performed by the Babelsberg Orchestra, conducted by Helmut Imig. In 2011 the most recent restoration was completed with an entirely new soundtrack by members of the Apskaft group. Contributing members were AER20-200, awaycaboose, Ditzky, Drn Drn, Foucault V, fydhws, Hox Vox, Lurholm, mexicanvader, Quendus, Res Band, -Soundso- and speculativism. The entire film was digitally restored to a sharper image by Gianluca Missero (who records under the name Hox Vox). The new version is available at the Internet Archive.[55]

A new score for Battleship Potemkin was composed in 2011 by Michael Nyman, and is regularly performed by the Michael Nyman Band. The Berklee Silent Film Orchestra also composed a new score for the film in 2011, and performed it live to picture at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in Washington, D.C. A new electroacoustic score by the composers collective Edison Studio was first performed live in Naples at Cinema Astra for Scarlatti Contemporanea Festival on 25 October 2017 [56] and published on DVD [57] in 5.1 surround sound by Cineteca di Bologna in the "L'Immagine Ritrovata" series, along with a second audio track with a recording of the Meisel's score conducted by Helmut Imig.

Critical response

[edit]Battleship Potemkin has received acclaim from modern critics. On review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an overall 100% approval rating based on 49 reviews, with a rating average of 9.20/10. The site's consensus reads, "A technical masterpiece, Battleship Potemkin is Soviet cinema at its finest, and its montage editing techniques remain influential to this day."[58] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 97 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[59]

Since its release Battleship Potemkin has often been cited as one of the finest propaganda films ever made, and is considered one of the greatest films of all time.[23][60] The film was named the greatest film of all time at the Brussels World's Fair in 1958.[3] Similarly, in 1952, Sight & Sound magazine cited Battleship Potemkin as the fourth-greatest film of all time; it was voted within the top ten in the magazine's five subsequent decennial polls, dropping to number 11 in the 2012 poll and number 54 in 2022.[61]

In 2007, a two-disc, restored version of the film was released on DVD. Time magazine's Richard Corliss named it one of the Top 10 DVDs of the year, ranking it at #5.[62] It ranked #3 in Empire's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[63] In April 2011, Battleship Potemkin was re-released in UK cinemas, distributed by the British Film Institute. On its re-release, Total Film magazine gave the film a five-star review, stating: "nearly 90 years on, Eisenstein's masterpiece is still guaranteed to get the pulse racing".[64]

Directors Orson Welles,[65] Michael Mann[66] and Paul Greengrass[67] placed Battleship Potemkin on their list of favorite films, and director Billy Wilder named it as his all-time favourite film.[40]

See also

[edit]- List of cult films

- List of films considered the best

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

References

[edit]- ^ Peter Rollberg (2016). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1442268425.

- ^ Snider, Eric (23 November 2010). "What's the Big Deal?: Battleship Potemkin (1925)". MTV News. MTV. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. "Battleship Potemkin". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Top Films of All-Time". Filmsite. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of All Time". British Film Institute. Sight & Sound. December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Motion Pictures, Art of; pages 499 & 525, Vol 12, Encyclopaedia Britannica Macropaedia

- ^ Наум И. Клейман; К. Б. Левина (eds.). Броненосец "Потемкин.". Шедевры советского кино. p. 24.

- ^ Marie Seton (1960). Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography. Grove Press. p. 74.

- ^ a b c d Jay Leyda (1960). Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. George Allen & Unwin. pp. 193–199.

- ^ Marie Seton (1960). Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography. Grove Press. pp. 79–82.

- ^ "Шедевр за два месяца". Gorodskie Novosti. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ Sergei Eisenstein (1959). Notes of a film director. Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 140.

- ^ Esfir Shub (1972). My Life — Cinema. Iskusstvo. p. 98.

- ^ Richard Taylor, Ian Christie, ed. (1994). The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 9781135082512.

- ^ a b c "Почему стоит снова посмотреть фильм "Броненосец "Потемкин"". rg.ru. 5 December 2013.

- ^ ""Потемкин" после реставрации". Pravda. 19 December 2008.

- ^ Sergei Eisenstein (1959). Notes of a film director. Foreign Languages Publishing House. pp. 18–23.

- ^ Martorell, Jordi (14 September 2004). "Pet Shop Boys meet Battleship Potemkin – Revolution in Trafalgar Square". In Defence of Marxism. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Hoskisson, Mark (22 February 2008). "Battleship Potemkin, Strike, October by Sergei Eisenstein: Appreciation". Permanent Revolution. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Bulleid, H. A. V. "Battleship Potemkin". Famous Library Films. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Winkler, Martin M. (2021). "The Medici Lions: Culture and Cinema from Rome to Alupka and Beyond". ClassicoContemporaneo. 7. ISSN 2421-4744. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ Neuberger, Joan (2003). Ivan the Terrible. New York: I. B. Tauris.

- ^ a b Snider, Eric. "What's the Big Deal?: Battleship Potemkin (1925)". MTV News. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Corney, Frederick C. "Battleship Potemkin". Directory of World Cinema. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "Heinrich Himmler: Order from Top SS Commander (Himmler) about Russian Propaganda Film". Germania International. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Winston, Brian (1 January 1997). "Triumph of the Will". History Today. Vol. 47, no. 1. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Seton, Marie (1960). Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography. Grove Press. pp. 326–327.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". British Board of Film Classification. 14 August 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "What Eisenstein created was the action sequence, which is absolutely vital to any modern film. ... Eisenstein's editing techniques have been used in any film made since that features any type of action sequence at all." Dylan Rambow (25 April 2015), "20 Influential Silent Films Every Movie Buff Should See", Taste of Cinema.

- ^ Andrew O'Hehir (12 January 2011), "How 'Battleship Potemkin' reshaped Hollywood", Salon

- ^ Bascomb, Neal (2008). Red Mutiny. Houghton Mifflin. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-547-05352-3.

- ^ Fabe, Marilyn (1 August 2004). Closely Watched Films: An Introduction to the Art of Narrative Film Technique. University of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-520-23862-1.

- ^ "During the night there were ... fierce conflicts between the troops and the rioters. The dead are reckoned in hundreds." "Havoc in the Town and Harbour", The Times, 30 June 1905, p. 5.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (19 July 1998). "The Battleship Potemkin", Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "Iconic movie scene: The Untouchables' Union Station shoot-out". Den of Geek. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Xan Brooks (1 February 2008). "Films influenced by Battleship Potemkin". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ Peppiatt, Michael (1996). Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81616-0.

- ^ Protzman, Ferdinand (2003). "Landscape. Photographs of Time and Place". National Geographic, ISBN 0-7922-6166-6

- ^ a b "News". Squire Artists. 18 May 2012.

- ^ Marie Seton (1960). Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography. Grove Press. p. 87.

- ^ Jay Leyda (1960). Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. George Allen & Unwin. p. 205.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". British Board of Film Classification. 30 September 1926. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

The BBFC determined this content to be unsuitable for classification at the time it was submitted.

- ^ Bryher (1922). Film Problems Of Soviet Russia. Riant Chateau TERRITET Switzerland. p. 31.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". British Board of Film Classification. 11 January 1954. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

Mild violence occurs during a massacre on the Odessa Steps which shows several people being shot and trampled on, with brief sight of bloody detail on the faces of the dead and injured.

- ^ "Case Study: Battleship Potemkin, Students' British Board of Film Classification website". Sbbfc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". British Board of Film Classification. 16 November 1987. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

Mild violence occurs during a massacre on the Odessa Steps which shows several people being shot and trampled on, with brief sight of bloody detail on the faces of the dead and injured.

- ^ "Soviet Films Hit by Foreign Censor, U.S. Is Liberal". Variety. New York City. 13 July 1928. p. 6. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Smith, Ian Haydn (20 September 2018). Selling the Movie: The Art of the Film Poster. White Lion Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7112-4025-4.

- ^ Gourianova, Nina (6 March 2012). The Aesthetics of Anarchy: Art and Ideology in the Early Russian Avant-Garde. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26876-0.

- ^ Ródchenko. Caso de estudio (PDF). IVAM.

- ^ a b c Institut Valencià d'Art Modern (2019). 50 obras maesstras de la Colección del IVAM: 1900-1950. Rocío Robles Tardóo. València: Institut Valencià d'Art Modern. ISBN 978-84-482-6416-1. OCLC 1241664690.

- ^ a b "El acorazado Potempkin - Alexander Rodchenko". HA! (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Underwood, Alice E. M. ""We invented and changed the world": A Rodchenko Art Gallery". Russian Life. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Apskaft Presents: The Battleship Potemkin". Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Prima esecuzione assoluta della sonorizzazione dal vivo de " La corazzata Potëmkin" - Associazione Scarlatti". Associazione Scarlatti (in Italian). 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ D-sign.it. "Libri, DVD & Gadgets - Cinestore". cinestore.cinetecadibologna.it. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin (1925)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Sight and Sound Historic Polls". BFI. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Corliss, Richard. "Top 10 DVDs". Time. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 3. The Battleship Potemkin". Empire.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". Total Film. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Fun Fridays – Director's Favourite Films – Orson Welles". Film Doctor. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Fun Fridays – Director's Favourite Films – Michael Mann". Film Doctor. 20 April 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Fun Fridays – Director's Favourite Films – Paul Greengrass". Film Doctor. 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Sergei Eisenstein (1959). Notes of a Film Director. Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Marie Seton (1960). Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography. Grove Press.

- Jay Leyda (1960). Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. George Allen & Unwin.

- Richard Taylor, Ian Christie, ed. (1994). The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents. Routledge.

- Bryher (1922). Film Problems Of Soviet Russia. Riant Chateau TERRITET Switzerland.

External links

[edit]- Battleship Potemkin at IMDb

- Battleship Potemkin at Rotten Tomatoes

- Battleship Potemkin on Russian Film Hub

- Battleship Potemkin is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive (version reworked in the USSR as described in § Production above)

- Battleship Potemkin at official Mosfilm site with English subtitles

- "Potemkin sailor monument". 2odessa.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2006. Monument in Odessa, explanation of the mutiny.

- Russo-Japanese War Connections Rebellion or Mutiny on the Potemkin had connection to Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05-Russian Navy morale was severely damaged.

- 1925 films

- Films originally rejected by the British Board of Film Classification

- 1920s historical drama films

- 1920s war drama films

- 1920s thriller films

- Soviet revolutionary propaganda films

- Soviet avant-garde and experimental films

- Soviet silent feature films

- Soviet epic films

- Soviet historical drama films

- Soviet war drama films

- Soviet thriller films

- Soviet black-and-white films

- Seafaring films based on actual events

- Films about mutinies

- Films about the Russian Revolution of 1905

- Films set in 1905

- Films set in Odesa

- Films set in 20th-century Russian Empire

- Films set on ships

- Films shot in Odesa

- Mosfilm films

- Films directed by Sergei Eisenstein

- Black Sea in fiction

- Censored films

- Potemkin mutiny

- Silent adventure films

- Films scored by Edmund Meisel

- 1920s historical films

- 1920s Russian-language films