Vaccine hesitancy

| Part of a series on |

| Vaccination |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Vaccine hesitancy is a delay in acceptance, or refusal, of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services and supporting evidence. The term covers refusals to vaccinate, delaying vaccines, accepting vaccines but remaining uncertain about their use, or using certain vaccines but not others.[1][2][3][4] Although adverse effects associated with vaccines are occasionally observed,[5] the scientific consensus that vaccines are generally safe and effective is overwhelming.[6][7][8][9] Vaccine hesitancy often results in disease outbreaks and deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases.[10][11][12][13][14][15] Therefore, the World Health Organization characterizes vaccine hesitancy as one of the top ten global health threats.[16][17]

Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context-specific, varying across time, place and vaccines.[18] It can be influenced by factors such as lack of proper scientifically based knowledge and understanding about how vaccines are made or work, as well as psychological factors including fear of needles[2] and distrust of public authorities, a person's lack of confidence (mistrust of the vaccine and/or healthcare provider), complacency (the person does not see a need for the vaccine or does not see the value of the vaccine), and convenience (access to vaccines).[3] It has existed since the invention of vaccination and pre-dates the coining of the terms "vaccine" and "vaccination" by nearly eighty years.[19]

"Anti-vaccinationism" refers to total opposition to vaccination; in more recent years, anti-vaccinationists have been known as "anti-vaxxers" or "anti-vax".[20] The specific hypotheses raised by anti-vaccination advocates have been found to change over time.[19] Anti-vaccine activism has been increasingly connected to political and economic goals.[21][22] Although myths, conspiracy theories, misinformation and disinformation spread by the anti-vaccination movement and fringe doctors leads to vaccine hesitancy and public debates around the medical, ethical, and legal issues related to vaccines, there is no serious hesitancy or debate within mainstream medical and scientific circles about the benefits of vaccination.[23]

Proposed laws that mandate vaccination, such as California Senate Bill 277 and Australia's No Jab No Pay, have been opposed by anti-vaccination activists and organizations.[24][25][26] Opposition to mandatory vaccination may be based on anti-vaccine sentiment, concern that it violates civil liberties or reduces public trust in vaccination, or suspicion of profiteering by the pharmaceutical industry.[12][27][28][29][30]

Effectiveness

Scientific evidence for the effectiveness of large-scale vaccination campaigns is well established.[31] Two to three million deaths are prevented each year worldwide by vaccination, and an additional 1.5 million deaths could be prevented each year if all recommended vaccines were used.[32] Vaccination campaigns helped eradicate smallpox, which once killed as many as one in seven children in Europe,[33] and have nearly eradicated polio.[34] As a more modest example, infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae (Hib), a major cause of bacterial meningitis and other serious diseases in children, have decreased by over 99% in the US since the introduction of a vaccine in 1988.[35] It is estimated that full vaccination, from birth to adolescence, of all US children born in a given year would save 33,000 lives and prevent 14 million infections.[36]

There is anti-vaccine literature that argues that reductions in infectious disease result from improved sanitation and hygiene (rather than vaccination) or that these diseases were already in decline before the introduction of specific vaccines. These claims are not supported by scientific data; the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases tended to fluctuate over time until the introduction of specific vaccines, at which point the incidence dropped to near zero. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website aimed at countering common misconceptions about vaccines argued, "Are we expected to believe that better sanitation caused the incidence of each disease to drop, just at the time a vaccine for that disease was introduced?"[37]

Another rallying cry of the anti-vaccine movement is to call for randomized clinical trials in which an experimental group of children are vaccinated while a control group are unvaccinated. Such a study would never be approved because it would require deliberately denying children standard medical care, rendering the study unethical. Studies have been done that compare vaccinated to unvaccinated people, but the studies are typically not randomized. Moreover, literature already exists that demonstrates the safety of vaccines using other experimental methods.[38]

Other critics argue that the immunity granted by vaccines is only temporary and requires boosters, whereas those who survive the disease become permanently immune.[12] As discussed below, the philosophies of some alternative medicine practitioners are incompatible with the idea that vaccines are effective.[39]

Population health

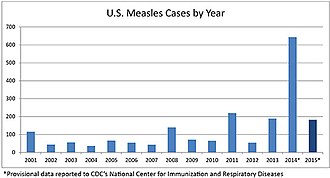

Incomplete vaccine coverage increases the risk of disease for the entire population, including those who have been vaccinated, because it reduces herd immunity. For example, the measles vaccine is given to children 9–12 months old, and the window between the disappearance of maternal antibody and seroconversion means that vaccinated children are frequently still vulnerable. Strong herd immunity reduces this vulnerability. Increasing herd immunity during an outbreak or when there is a risk of an outbreak is perhaps the most widely accepted justification for mass vaccination. When a new vaccine is introduced, mass vaccination can help increase coverage rapidly.[43]

If enough of a population is vaccinated, herd immunity takes effect, decreasing risk to people who cannot receive vaccines because they are too young or old, immunocompromised, or have severe allergies to the ingredients in the vaccine.[44] The outcome for people with compromised immune systems who get infected is often worse than that of the general population.[45]

Cost-effectiveness

Commonly used vaccines are a cost-effective and preventive way of promoting health, compared to the treatment of acute or chronic disease. In 2001, the United States spent approximately $2.8 billion to promote and implement routine childhood immunizations against seven diseases. The societal benefits of those vaccinations were estimated to be $46.6 billion, yielding a benefit-cost ratio of 16.5.[46]

Necessity

When a vaccination program successfully reduces the disease threat, it may reduce the perceived risk of disease as cultural memories of the effects of that disease fade. At this point, parents may feel they have nothing to lose by not vaccinating their children.[47] If enough people hope to become free-riders, gaining the benefits of herd immunity without vaccination, vaccination levels may drop to a level where herd immunity is ineffective.[48] According to Jennifer Reich, those parents who believe vaccination to be quite effective but might prefer their children to remain unvaccinated, are those who are the most likely to be convinced to change their mind, as long as they are approached properly.[49]

Safety concerns

While some anti-vaccinationists openly deny the improvements vaccination has made to public health or believe in conspiracy theories,[12] it is much more common to cite concerns about safety.[50] As with any medical treatment, there is a potential for vaccines to cause serious complications, such as severe allergic reactions,[51] but unlike most other medical interventions, vaccines are given to healthy people and so a higher standard of safety is demanded.[52] While serious complications from vaccinations are possible, they are extremely rare and much less common than similar risks from the diseases they prevent.[37] As the success of immunization programs increases and the incidence of disease decreases, public attention shifts away from the risks of disease to the risk of vaccination,[53] and it becomes challenging for health authorities to preserve public support for vaccination programs.[54]

The overwhelming success of certain vaccinations has made certain diseases rare, and, consequently, has led to incorrect heuristic thinking in weighing risks against benefits among people who are vaccine-hesitant.[55] Once such diseases (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae B) decrease in prevalence, people may no longer appreciate how serious the illness is due to a lack of familiarity with it and become complacent.[55] The lack of personal experience with these diseases reduces the perceived danger and thus reduces the perceived benefit of immunization.[56] Conversely, certain illnesses (e.g., influenza) remain so common that vaccine-hesitant people mistakenly perceive the illness to be non-threatening despite clear evidence that the illness poses a significant threat to human health.[55] Omission and disconfirmation biases also contribute to vaccine hesitancy.[55][57]

Various concerns about immunization have been raised. They have been addressed and the concerns are not supported by evidence.[56] Concerns about immunization safety often follow a pattern. First, some investigators suggest that a medical condition of increasing prevalence or unknown cause is an adverse effect of vaccination. The initial study and subsequent studies by the same group have an inadequate methodology, typically a poorly controlled or uncontrolled case series. A premature announcement is made about the alleged adverse effect, resonating with individuals who have the condition, and underestimating the potential harm of forgoing vaccination to those whom the vaccine could protect. Other groups attempt to replicate the initial study but fail to get the same results. Finally, it takes several years to regain public confidence in the vaccine.[53] Adverse effects ascribed to vaccines typically have an unknown origin, an increasing incidence, some biological plausibility, occurrences close to the time of vaccination, and dreaded outcomes.[58] In almost all cases, the public health effect is limited by cultural boundaries: English speakers worry about one vaccine causing autism, while French speakers worry about another vaccine causing multiple sclerosis, and Nigerians worry that a third vaccine causes infertility.[59]

Thiomersal

Thiomersal (called "thimerosal" in the US) is an antifungal preservative used in small amounts in some multi-dose vaccines (where the same vial is opened and used for multiple patients) to prevent contamination of the vaccine.[60] Despite thiomersal's efficacy, the use of thiomersal is controversial because it can be metabolized or degraded in the body to ethylmercury (C2H5Hg+) and thiosalicylate.[61][62] As a result, in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) asked vaccine makers to remove thiomersal from vaccines as quickly as possible on the precautionary principle. Thiomersal is now absent from all common US and European vaccines, except for some preparations of influenza vaccine.[63] Trace amounts remain in some vaccines due to production processes, at an approximate maximum of one microgramme, around 15% of the average daily mercury intake in the US for adults and 2.5% of the daily level considered tolerable by the WHO.[62][64] The action sparked concern that thiomersal could have been responsible for autism.[63] The idea is now considered disproven, as incidence rates for autism increased steadily even after thiomersal was removed from childhood vaccines.[19] Currently there is no accepted scientific evidence that exposure to thiomersal is a factor in causing autism.[65][66] Since 2000, parents in the United States have pursued legal compensation from a federal fund arguing that thiomersal caused autism in their children.[67] A 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee favored rejecting any causal relationship between thiomersal-containing vaccines and autism.[68] The concentration of thiomersal used in vaccines as an antimicrobial agent ranges from 0.001% (1 part in 100,000) to 0.01% (1 part in 10,000).[69] A vaccine containing 0.01% thiomersal has 25 micrograms of mercury per 0.5 mL dose, roughly the same amount of elemental mercury found in a three-ounce (85 g) can of tuna.[69] There is robust peer-reviewed scientific evidence supporting the safety of thiomersal-containing vaccines.[69]

MMR vaccine

In the UK, the MMR vaccine was the subject of controversy after the publication in The Lancet of a 1998 paper by Andrew Wakefield and others reporting case histories of twelve children mostly with autism spectrum disorders with onset soon after administration of the vaccine.[70] At a 1998 press conference, Wakefield suggested that giving children the vaccines in three separate doses would be safer than a single vaccination. This suggestion was not supported by the paper, and several subsequent peer-reviewed studies have failed to show any association between the vaccine and autism.[71] It later emerged that Wakefield had received funding from litigants against vaccine manufacturers and that he had not informed colleagues or medical authorities of his conflict of interest: Wakefield reportedly stood to earn up to $43 million per year selling diagnostic kits.[72][73] Had this been known, publication in The Lancet would not have taken place in the way that it did.[74] Wakefield has been heavily criticized on scientific and ethical grounds for the way the research was conducted[75] and for triggering a decline in vaccination rates, which fell in the UK to 80% in the years following the study.[76][77] In 2004, the MMR-and-autism interpretation of the paper was formally retracted by ten of its thirteen coauthors,[78] and in 2010 The Lancet's editors fully retracted the paper.[79][80] Wakefield was struck off the UK medical register, with a statement identifying deliberate falsification in the research published in The Lancet,[81] and is barred from practicing medicine in the UK.[82]

The CDC, the IOM of the National Academy of Sciences, Australia's Department of Health, and the UK National Health Service have all concluded that there is no evidence of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.[68][83][84][85] A Cochrane review concluded that there is no credible link between the MMR vaccine and autism, that MMR has prevented diseases that still carry a heavy burden of death and complications, that the lack of confidence in MMR has damaged public health, and that the design and reporting of safety outcomes in MMR vaccine studies are largely inadequate.[86] Additional reviews agree, with studies finding that vaccines are not linked to autism even in high risk populations with autistic siblings.[87]

In 2009, The Sunday Times reported that Wakefield had manipulated patient data and misreported results in his 1998 paper, creating the appearance of a link with autism.[88] A 2011 article in the British Medical Journal described how the data in the study had been falsified by Wakefield so that it would arrive at a predetermined conclusion.[89] An accompanying editorial in the same journal described Wakefield's work as an "elaborate fraud" that led to lower vaccination rates, putting hundreds of thousands of children at risk and diverting energy and money away from research into the true cause of autism.[90]

A special court convened in the United States to review claims under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program ruled on February 12, 2009, that the evidence "failed to demonstrate that thimerosal-containing vaccines can contribute to causing immune dysfunction, or that the MMR vaccine can contribute to causing either autism or gastrointestinal dysfunction", and that parents of autistic children were therefore not entitled to compensation in their contention that certain vaccines caused autism in their children.[91]

Vaccine overload

Vaccine overload, a non-medical term, is the notion that giving many vaccines at once may overwhelm or weaken a child's immature immune system and lead to adverse effects.[92] Despite scientific evidence that strongly contradicts this idea,[19] there are still parents of autistic children that believe that vaccine overload causes autism.[93] The resulting controversy has caused many parents to delay or avoid immunizing their children.[92] Such parental misperceptions are major obstacles towards immunization of children.[94]

The concept of vaccine overload is flawed on several levels.[19] Despite the increase in the number of vaccines over recent decades, improvements in vaccine design have reduced the immunologic load from vaccines; the total number of immunological components in the 14 vaccines administered to US children in 2009 is less than ten percent of what it was in the seven vaccines given in 1980.[19] A study published in 2013 found no correlation between autism and the antigen number in the vaccines the children were administered up to the age of two. There were 1,008 children in the study, one quarter of whom were diagnosed with autism, and the whole cohort was born between 1994 and 1999, when the routine vaccine schedule could contain more than 3,000 antigens (in a single shot of DTP vaccine). The vaccine schedule in 2012 contains several more vaccines, but the number of antigens the child is exposed to by the age of two is 315.[95][96] Vaccines pose a very small immunologic load compared to the pathogens naturally encountered by a child in a typical year;[19] common childhood conditions such as fevers and middle-ear infections pose a much greater challenge to the immune system than vaccines,[97] and studies have shown that vaccinations, even multiple concurrent vaccinations, do not weaken the immune system[19] or compromise overall immunity.[98] The lack of evidence supporting the vaccine overload hypothesis, combined with these findings directly contradicting it, has led to the conclusion that currently recommended vaccine programs do not "overload" or weaken the immune system.[53][99][100][101]

Any experiment based on withholding vaccines from children is considered unethical,[102] and observational studies would likely be confounded by differences in the healthcare-seeking behaviors of under-vaccinated children. Thus, no study directly comparing rates of autism in vaccinated and unvaccinated children has been done. However, the concept of vaccine overload is biologically implausible, as vaccinated and unvaccinated children have the same immune response to non-vaccine-related infections, and autism is not an immune-mediated disease, so claims that vaccines could cause it by overloading the immune system go against current knowledge of the pathogenesis of autism. As such, the idea that vaccines cause autism has been effectively dismissed by the weight of current evidence.[19]

Prenatal infection

There is evidence that schizophrenia is associated with prenatal exposure to rubella, influenza, and toxoplasmosis infection. For example, one study found a sevenfold increased risk of schizophrenia when mothers were exposed to influenza in the first trimester of gestation. This may have public health implications, as strategies for preventing infection include vaccination, simple hygiene, and, in the case of toxoplasmosis, antibiotics.[103] Based on studies in animal models, theoretical concerns have been raised about a possible link between schizophrenia and maternal immune response activated by virus antigens; a 2009 review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend routine use of trivalent influenza vaccine during the first trimester of pregnancy, but that the vaccine was still recommended outside the first trimester and in special circumstances such as pandemics or in women with certain other conditions.[104] The CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians all recommend routine flu shots for pregnant women, for several reasons:[105]

- their risk for serious influenza-related medical complications during the last two trimesters;

- their greater rates for flu-related hospitalizations compared to non-pregnant women;

- the possible transfer of maternal anti-influenza antibodies to children, protecting the children from the flu; and

- several studies that found no harm to pregnant women or their children from the vaccinations.

Despite this recommendation, only 16% of healthy pregnant US women surveyed in 2005 had been vaccinated against the flu.[105]

Ingredient concerns

Aluminum compounds are used as immunologic adjuvants to increase the effectiveness of many vaccines.[106] The aluminum in vaccines simulates or causes small amounts of tissue damage, driving the body to respond more powerfully to what it sees as a serious infection and promoting the development of a lasting immune response.[107][108] In some cases these compounds have been associated with redness, itching, and low-grade fever,[107] but the use of aluminum in vaccines has not been associated with serious adverse events.[106][109] In some cases, aluminum-containing vaccines are associated with macrophagic myofasciitis (MMF), localized microscopic lesions containing aluminum salts that persist for up to 8 years. However, recent case-controlled studies have found no specific clinical symptoms in individuals with biopsies showing MMF, and there is no evidence that aluminum-containing vaccines are a serious health risk or justify changes to immunization practice.[106][109] Infants are exposed to greater quantities of aluminum in daily life in breastmilk and infant formula than in vaccines.[2] In general, people are exposed to low levels of naturally occurring aluminum in nearly all foods and drinking water.[110] The amount of aluminum present in vaccines is small, less than one milligram, and such low levels are not believed to be harmful to human health.[110]

In 2015., N. Petrovsky, summarizing the current evidence on the vaccine adjuvants, writes: "Unfortunately, adjuvant research has lagged behind other vaccine areas... the biggest remaining challenge in the adjuvant field is to decipher the potential relationship between adjuvants and rare vaccine adverse reactions, such as narcolepsy, macrophagic myofasciitis or Alzheimer's disease. While existing adjuvants based on aluminium salts have a strong safety record, there are ongoing needs for new adjuvants and more intensive research into adjuvants and their effects."[111] In 2023, Łukasz Bryliński writes: "Even though its toxicity is well-documented, the role of Al in the pathogenesis of several neurological diseases remains debatable...Despite poor absorption via mucosa, the biggest amount of Al comes with food, drinking water, and inhalation. Vaccines introduce negligible amounts of Al, while the data on skin absorption (which might be linked with carcinogenesis) is limited and requires further investigation...Although we know for sure that Al accumulates in the brain, it is not fully understood how it reaches it."[112]

Vaccine hesitant people have also voiced strong concerns about the presence of formaldehyde in vaccines. Formaldehyde is used in very small concentrations to inactivate viruses and bacterial toxins used in vaccines.[113] Very small amounts of residual formaldehyde can be present in vaccines but are far below values harmful to human health.[114][115] The levels present in vaccines are minuscule when compared to naturally occurring levels of formaldehyde in the human body and pose no significant risk of toxicity.[113] The human body continuously produces formaldehyde naturally and contains 50–70 times the greatest amount of formaldehyde present in any vaccine.[113] Furthermore, the human body is capable of breaking down naturally occurring formaldehyde as well as the small amount of formaldehyde present in vaccines.[113] There is no evidence linking the infrequent exposures to small quantities of formaldehyde present in vaccines with cancer.[113]

Sudden infant death syndrome

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is most common in infants around the time in life when they receive many vaccinations.[116] Since the cause of SIDS has not been fully determined, this led to concerns about whether vaccines, in particular diphtheria-tetanus toxoid vaccines, were a possible causal factor.[116] Several studies investigated this and found no evidence supporting a causal link between vaccination and SIDS.[116][117] In 2003, the Institute of Medicine favored rejection of a causal link to DTwP vaccination and SIDS after reviewing the available evidence.[118] Additional analyses of VAERS data also showed no relationship between vaccination and SIDS.[116] Studies have shown a negative correlation between SIDs and vaccination. That is vaccinated children are less likely to die but no causal link has been found. One suggestion is that infants who are less likely to develop SIDS are more likely to be presented for vaccination.[116][117][119]

Anthrax vaccines

In the mid-1990s media reports on vaccines discussed the Gulf War Syndrome, a multi-symptomatic disorder affecting returning US military veterans of the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf War. Among the first articles of the online magazine Slate was one by Atul Gawande in which the required immunizations received by soldiers, including an anthrax vaccination, were named as one of the likely culprits for the symptoms associated with the Gulf War Syndrome. In the late 1990s Slate published an article on the "brewing rebellion" in the military against anthrax immunization because of "the availability to soldiers of vaccine misinformation on the Internet". Slate continued to report on concerns about the required anthrax and smallpox immunization for US troops after the September 11 attacks and articles on the subject also appeared on the Salon website.[120] The 2001 anthrax attacks heightened concerns about bioterrorism and the Federal government of the United States stepped up its efforts to store and create more vaccines for American citizens.[120] In 2002, Mother Jones published an article that was highly skeptical of the anthrax and smallpox immunization required by the United States Armed Forces.[120] With the 2003 invasion of Iraq a wider controversy ensued in the media about requiring US troops to be vaccinated against anthrax.[120] From 2003 to 2008 a series of court cases were brought to oppose the compulsory anthrax vaccination of US troops.[120]

Swine flu vaccine

The US swine flu immunization campaign in response to the 1976 swine flu outbreak has become known as "the swine flu fiasco" because the outbreak did not lead to a pandemic as US President Gerald Ford had feared and the hastily rolled out vaccine was found to increase the number of Guillain–Barré Syndrome cases two weeks after immunization. Government officials stopped the mass immunization campaign due to great anxiety about the safety of the swine flu vaccine. The general public was left with greater fear of the vaccination campaign than the virus itself, and vaccination policies, in general, were challenged.[121]: 8

During the 2009 flu pandemic, significant controversy broke out regarding whether the 2009 H1N1 flu vaccine was safe in, among other countries, France. Numerous different French groups publicly criticized the vaccine as potentially dangerous.[122] Because of similarities between the 2009 influenza A subtype H1N1 virus and the 1976 influenza A/NJ virus many countries established surveillance systems for vaccine-related adverse effects on human health. A possible link between the 2009 H1N1 flu vaccine and Guillain–Barré Syndrome cases was studied in Europe and the United States.[121]: 325

Blood transfusion

After the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, vaccine hesitant people have at times demanded that they get donor blood from donors that have not received the vaccine. In the US and Canada, blood centers do not keep data on whether a donor has been COVID-19 infected or vaccinated, and in August 2021 it was estimated that 60-70% of US blood donors had COVID-19 antibodies. Research director Timothy Caulfield said that "This really highlights, I think, how powerful misinformation can be. It can really have an impact in a way that can be dangerous ... There is no evidence to support these concerns."[123][124][125]

As of August 2021, such demands are rare in the US.[123] Doctors in Alberta, Canada, warned in November 2022 that the demands were becoming more common.[125]

In Italy and New Zealand, parents have gone to court to stop their children's urgent heart surgery, unless COVID-19 vaccine free blood was provided. In both cases the parents were ruled against, though they stated that they could provide willing donors they found acceptable.[126][127][128] The New Zealand Blood Service does not label blood according to the donor's COVID-19 vaccine history,[129] and as of 2022, about 90% of New Zealand's population over twelve years of age has had two COVID-19 vaccinations.[130] In another Italian case, a blood transfusion for a sick 90-year-old man was refused by his two daughters, due to vaccine hesitancy concerns.[126] Another New Zealand couple stated that they were trying to arrange their child to have her next heart surgery in India, to avoid her being given blood from COVID-19 vaccinated donors.[131]

Other safety concerns

Other safety concerns about vaccines have been promoted on the Internet, in informal meetings, in books, and at symposia. These include hypotheses that vaccination can cause epileptic seizures, allergies, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, as well as hypotheses that vaccinations can transmit bovine spongiform encephalopathy, hepatitis C virus, and HIV. These hypotheses have been investigated, with the conclusion that currently used vaccines meet high safety standards and that criticism of vaccine safety in the popular press is not justified.[56][101][132][133] Large well-controlled epidemiologic studies have been conducted and the results do not support the hypothesis that vaccines cause chronic diseases. Furthermore, some vaccines are probably more likely to prevent or modify than cause or exacerbate autoimmune diseases.[100][134] Another common concern parents often have is about the pain associated with administering vaccines during a doctor's office visit.[135] This may lead to parental requests to space out vaccinations; however, studies have shown a child's stress response is not different when receiving one vaccination or two. The act of spacing out vaccinations may actually lead to more stressful stimuli for the child.[2]

Vaccine myths and misinformation

Several vaccination myths contribute to parental concerns and vaccine hesitancy. These include the alleged superiority of natural infection when compared to vaccination, questioning whether the diseases vaccines prevent are dangerous, whether vaccines pose moral or religious dilemmas, suggesting that vaccines are not effective, proposing unproven or ineffective approaches as alternatives to vaccines, and conspiracy theories that center on mistrust of the government and medical institutions.[32]

Autism

The idea of a link between vaccines and autism has been extensively investigated and conclusively shown to be false.[136][137] The scientific consensus is that there is no relationship, causal or otherwise, between vaccines and incidence of autism,[53][138][136] and vaccine ingredients do not cause autism.[139]

Nevertheless, the anti-vaccination movement continues to promote myths, conspiracy theories, and misinformation linking the two.[140] A developing tactic appears to be the "promotion of irrelevant research [as] an active aggregation of several questionable or peripherally related research studies in an attempt to justify the science underlying a questionable claim", to quote the Skeptical Inquirer.[141]

Vaccination during illness

Many parents are concerned about the safety of vaccination when their child is sick.[2] Moderate to severe acute illness with or without a fever is indeed a precaution when considering vaccination.[2] Vaccines remain effective during childhood illness.[2] The reason vaccines may be withheld if a child is moderately to severely ill is because certain expected side effects of vaccination (e.g. fever or rash) may be confused with the progression of the illness.[2] It is safe to administer vaccines to well-appearing children who are mildly ill with the common cold.[2]

Natural infection

Another common anti-vaccine myth is that the immune system produces a better immune protection in response to natural infection when compared to vaccination.[2] However, strength and duration of immune protection gained varies by both disease and vaccine, with some vaccines giving better protection than natural infection. For example, the HPV vaccine generates better immune protection than natural infection due to the vaccine containing higher concentrations of a viral coat protein, while also not containing proteins the HPV viruses use to inhibit immune response.[142]

While it is true that infection with certain illnesses may produce lifelong immunity, many natural infections do not produce lifelong immunity, while carrying a higher risk of harming a person's health than vaccines.[2] For example, natural varicella infection carries a higher risk of bacterial superinfection with Group A streptococci.[2]

Natural measles infection carries a high risk of many serious, and sometimes life-long, complications, all of which can be avoided by vaccination. Those infected with measles rarely have a symptomatic reinfection.[143]

Most people survive measles, though in some cases, complications may occur. Among those that experience complications, about 1 in 4 individuals will be hospitalized and 1–2 in 1000 will die. Complications are more likely in children under age 5 and adults over age 20.[144] Pneumonia is the most common fatal complication of measles infection and accounts for 56–86% of measles-related deaths.[145]

Possible consequences of measles virus infection include laryngotracheobronchitis, sensorineural hearing loss,[146] and—in about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 300,000 cases[147]—panencephalitis, which is usually fatal.[148] Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs two days to one week after the measles rash breaks out and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions and altered mentation. A person with measles encephalitis may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.[149]

The measles virus can deplete previously acquired immune memory by killing cells that make antibodies, and thus weakens the immune system which can cause deaths from other diseases.[150][151][152] Suppression of the immune system by measles lasts about two years and has been epidemiologically implicated in up to 90% of childhood deaths in third world countries, and historically may have caused rather more deaths in the United States, the UK and Denmark than were directly caused by measles.[153] Although the measles vaccine contains an attenuated strain, it does not deplete immune memory.[151]

HPV vaccine

The idea that the HPV vaccine is linked to increased sexual behavior is not supported by scientific evidence. A review of nearly 1,400 adolescent girls found no difference in teen pregnancy, the incidence of sexually transmitted infection, or contraceptive counseling regardless of whether they received the HPV vaccine.[2] Thousands of Americans die each year from cancers preventable by the vaccine.[2]

There remains a disproportionate rate of HPV-related cancers amongst LatinX populations, leading researchers to explore how messaging may be made more effective to address vaccine hesitancy.[154]

Vaccine schedule

Other concerns have been raised about the vaccine schedule recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). The immunization schedule is designed to protect children against preventable diseases when they are most vulnerable. The practice of delaying or spacing out these vaccinations increases the amount of time the child is susceptible to these illnesses.[2] Receiving vaccines on the schedule recommended by the ACIP is not linked to autism or developmental delay.[2]

Information warfare

An analysis of tweets from July 2014 through September 2017 revealed an active campaign on Twitter by the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian troll farm accused of interference in the 2016 U.S. elections, to sow discord about the safety of vaccines.[155][156] The campaign used sophisticated Twitter bots to amplify polarizing pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine messages, containing the hashtag #VaccinateUS, posted by IRA trolls.[155]

Alternative medicine

Many forms of alternative medicine are based on philosophies that oppose vaccination (including germ theory denialism) and have practitioners who voice their opposition. As a consequence, the increase in popularity of alternative medicine in the 1970s planted the seeds of the modern anti-vaccination movement.[157] More specifically, some elements of the chiropractic community, some homeopaths, and naturopaths developed anti-vaccine rhetoric.[39] The reasons for this negative vaccination view are complicated and rest at least in part on the early philosophies that shaped the foundation of these groups.[39]

Chiropractic

Historically, chiropractic strongly opposed vaccination based on its belief that all diseases were traceable to causes in the spine and therefore could not be affected by vaccines. Daniel D. Palmer (1845–1913), the founder of chiropractic, wrote: "It is the very height of absurdity to strive to 'protect' any person from smallpox or any other malady by inoculating them with a filthy animal poison."[158] Vaccination remains controversial within the profession.[159] Most chiropractic writings on vaccination focus on its negative aspects.[158] A 1995 survey of US chiropractors found that about one third believed there was no scientific proof that immunization prevents disease.[159] While the Canadian Chiropractic Association supports vaccination,[158] a survey in Alberta in 2002 found that 25% of chiropractors advised patients for, and 27% advised against, vaccinations for patients or for their children.[160]

Although most chiropractic colleges try to teach about vaccination in a manner consistent with scientific evidence, several have faculty who seem to stress negative views.[159] A survey of a 1999–2000 cross-section of students of Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC), which does not formally teach anti-vaccination views, reported that fourth-year students opposed vaccination more strongly than did first-year students, with 29.4% of fourth-year students opposing vaccination.[161] A follow-up study on 2011–12 CMCC students found that pro-vaccination attitudes heavily predominated. Students reported support rates ranging from 84% to 90%. One of the study's authors proposed the change in attitude to be due to the lack of the previous influence of a "subgroup of some charismatic students who were enrolled at CMCC at the time, students who championed the Palmer postulates that advocated against the use of vaccination".[162]

Policy positions

The American Chiropractic Association and the International Chiropractic Association support individual exemptions to compulsory vaccination laws.[159] In March 2015, the Oregon Chiropractic Association invited Andrew Wakefield, chief author of a fraudulent research paper, to testify against Senate Bill 442,[163] "a bill that would eliminate nonmedical exemptions from Oregon's school immunization law".[164] The California Chiropractic Association lobbied against a 2015 bill ending belief exemptions for vaccines. They had also opposed a 2012 bill related to vaccination exemptions.[165]

Homeopathy

Several surveys have shown that some practitioners of homeopathy, particularly homeopaths without any medical training, advise patients against vaccination.[166] For example, a survey of registered homeopaths in Austria found that only 28% considered immunization an important preventive measure, and 83% of homeopaths surveyed in Sydney, Australia, did not recommend vaccination.[39] Many practitioners of naturopathy also oppose vaccination.[39]

Homeopathic "vaccines" (nosodes) are ineffective because they do not contain any active ingredients and thus do not stimulate the immune system. They can be dangerous if they take the place of effective treatments.[167] Some medical organizations have taken action against nosodes. In Canada, the labeling of homeopathic nosodes require the statement: "This product is neither a vaccine nor an alternative to vaccination."[168]

Financial motives

Alternative medicine proponents gain from promoting vaccine conspiracy theories through the sale of ineffective and expensive medications, supplements, and procedures such as chelation therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, sold as able to cure the 'damage' caused by vaccines.[169] Homeopaths in particular gain through the promotion of water injections or 'nosodes' that they allege have a 'natural' vaccine-like effect.[170] Additional bodies with a vested interest in promoting the "unsafeness" of vaccines may include lawyers and legal groups organizing court cases and class action lawsuits against vaccine providers.

Conversely, alternative medicine providers have accused the vaccine industry of misrepresenting the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, covering up and suppressing information, and influencing health policy decisions for financial gain.[12] In the late 20th century, vaccines were a product with low profit margins,[171] and the number of companies involved in vaccine manufacture declined. In addition to low profits and liability risks, manufacturers complained about low prices paid for vaccines by the CDC and other US government agencies.[172] In the early 21st century, the vaccine market greatly improved with the approval of the vaccine Prevnar, along with a small number of other high-priced blockbuster vaccines, such as Gardasil and Pediarix, which each had sales revenues of over $1 billion in 2008.[171] Despite high growth rates, vaccines represent a relatively small portion of overall pharmaceutical profits. As recently as 2010, the World Health Organization estimated vaccines to represent 2–3% of total sales for the pharmaceutical industry.[173]

Psychological factors

The rise in vaccine hesitancy has led to research on the psychology of those who actively oppose vaccines.The largest psychological factors leading to anti-vaccination attitudes are conspiratorial thinking, reactance, disgust regarding blood or needles, and individualistic or hierarchical worldviews. In contrast, demographic variables are not significant.[174]

Researchers have also investigated the psychological roots of vaccine hesitancy with regard to specific vaccines. For instance, a 2021 study published in Nature Communications investigated psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the UK. The study found that vaccine hesitant or resistant respondents in the two countries varied across socio-demographic and health-related variables, however, they were similar in range of psychological factors. Such respondents were less likely to obtain information about the pandemic from authoritative and traditional media sources and demonstrated similar skepticism towards these sources compared to respondents who accepted the vaccine.[175]

Fear of needles

Blood-injection-injury phobia and general fear of needles and injections can lead people to avoid vaccinations. One survey conducted in January and February 2021 estimated this was responsible for 10% of the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK at the time.[176][177] A 2012 survey of American parents found that a fear of needles was the most common reason for adolescents to forgo their second dose of a HPV vaccine.[178][179]

Various treatments for fear of needles can help overcome this problem, from offering pain reduction at the time of injection to long-term behavioral therapy.[178] Tensing the stomach muscles can help avoid fainting, swearing can reduce perceived pain, and distraction can also improve the perceived experience, such as by pretending to cough, performing a visual task, watching a video, or playing a video game.[178] To avoid dissuading people who have a needle phobia, vaccine update researchers recommend against using pictures of needles, people getting an injection, or faces displaying negative emotions (like a crying baby) in promotional materials. Instead, they recommend medically accurate photos depicting smiling, diverse people with bandages, vaccination cards, or a rolled-up sleeve; depicting vials instead of needles; and depicting the people who develop and test vaccines.[180] Development of vaccines that can be administered orally or with a jet injector can also avoid triggering the fear of needles.[181]

Social factors

Beyond misinformation, social and economic conditions also influence how many people take vaccines. Factors such as income, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age, and education can determine the uptake of vaccines and their impact, especially among vulnerable communities.[182]

Social factors like whether one lives with others may affect vaccine uptake. For example, older individuals who live alone are much more likely not to take up vaccines compared to those living with other people.[183] Other factors may be racial, with minority groups being affected by low vaccine uptake.[184]

People with weaker immune systems or chronic illness are more likely to take up a vaccine if recommended by their physicians.[185]

Other reasons

Unethical human experimentation and medical racism

Some people in groups experiencing medical racism are less willing to trust doctors and modern medicine due to real historical incidents of unethical human experimentation and involuntary sterilization. Famous examples include drug trials in Africa without informed consent, the Guatemala syphilis experiments,[186][187] the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the culturing of cells from Henrietta Lacks without consent, and Nazi human experimentation.

To overcome this type of distrust, experts recommend including representative samples of majority and minority populations in drug trials, including minority groups in study design, being diligent about informed consent, and being transparent about the process of drug design and testing.[188]

Malpractice and fraud

CIA fake vaccination clinic

In Pakistan, the CIA ran a fake vaccination clinic in an attempt to locate Osama bin Laden.[189][190] As a direct consequence, there have been several attacks and deaths among vaccination workers. Several Islamist preachers and militant groups, including some factions of the Taliban, view vaccination as a plot to kill or sterilize Muslims.[191] Efforts to eradicate polio have furthermore been disrupted by American drone strikes.[189] Pakistan is among the only countries where polio remained endemic as of 2015.[192]

Fake COVID-19 vaccines

In July 2021, Indian police arrested 14 people for administering doses of saline solution instead of the AstraZeneca vaccine at nearly a dozen private vaccination sites in Mumbai. The organizers, including medical professionals, charged between $10 and $17 for each dose, and more than 2,600 people paid to receive what they thought was the vaccine.[193][194] The federal government downplayed the scandal, claiming these cases were isolated. McAfee stated India was among the top countries to have been targeted by fake apps to lure people with a promise of vaccines.[195]

In Bhopal, slum residents were misled into thinking they would get an approved COVID-19 vaccine, but instead were actually part of an experimental clinical trial for the domestic vaccine Covaxin. Only 50% of participants in the trials received a vaccine with the rest receiving a placebo. One participant stated, "...I didn't know that there was a possibility you could get a water shot."[196][197]

Religion

Since most religions predate the invention of vaccines, scriptures do not specifically address the topic of vaccination.[2] However, vaccination has been opposed by some on religious grounds ever since it was first introduced. When vaccination was first becoming widespread, some Christian opponents argued that preventing smallpox deaths would be thwarting God's will and that such prevention is sinful.[198] Opposition from some religious groups continues to the present day, on various grounds, raising ethical difficulties when the number of unvaccinated children threatens harm to the entire population.[199] Many governments allow parents to opt out of their children's otherwise mandatory vaccinations for religious reasons; some parents falsely claim religious beliefs to get vaccination exemptions.[200]

Many Jewish community leaders support vaccination.[201] Among early Hasidic leaders, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810) was known for his criticism of the doctors and medical treatments of his day. However, when the first vaccines were successfully introduced, he stated: "Every parent should have his children vaccinated within the first three months of life. Failure to do so is tantamount to murder. Even if they live far from the city and have to travel during the great winter cold, they should have the child vaccinated before three months."[202]

Although gelatin can be derived from many animals, Jewish and Islamic scholars have determined that since the gelatin is cooked and not consumed as food, vaccinations containing gelatin are acceptable.[2] However, in 2015 and again in 2020, the possible use of porcine-based gelatin in vaccines raised religious concerns among Muslims and Orthodox Jews about the halal or kosher status of several vaccinations against COVID-19.[203] The Muslim Council of Britain raised concern about the UK's intranasal influenza vaccine deployment in 2019 due to the presence of gelatin in the vaccine. The MCB subsequently clarified that it never advised against the vaccine, it did not have any religious authority to issue a fatwa on the matter, and that vaccines containing porcine gelatin are generally not considered haram if alternatives are unavailable (the injectable flu vaccine was also offered in Scotland, but not England).[204]

In India, in 2018, a three-minute doctored clip circulated among Muslims claiming that the MR-VAC vaccine against measles and rubella was a "Modi government-RSS conspiracy" to stop the population growth of Muslims. The clip was taken from a TV show that exposed the baseless rumors.[205] Hundreds of madrassas in the state of Uttar Pradesh refused permission to health department teams to administer vaccines because of rumors spread using WhatsApp.[206]

Some Christians have objected to the use of cell cultures of some viral vaccines, and the virus of the rubella vaccine,[207] on the grounds that they are derived from tissues taken from therapeutic abortions performed in the 1960s. The principle of double effect, originated by Thomas Aquinas, holds that actions with both good and bad consequences are morally acceptable in specific circumstances.[208] The Vatican Curia has said that for vaccines originating from embryonic cells, Catholics have "a grave responsibility to use alternative vaccines and to make a conscientious objection", but concluded that it is acceptable for Catholics to use the existing vaccines until an alternative becomes available.[209]

In the United States, some parents falsely claim religious exemptions when their real motivation for avoiding vaccines is supposed safety concerns.[210] For a number of years, only Mississippi, West Virginia, and California did not provide religious exemptions. Following the 2019 measles outbreaks, Maine and New York repealed their religious exemptions, and the state of Washington did so for the measles vaccination.[211]

According to a March 2021 poll conducted by The Associated Press/NORC, vaccine skepticism is more widespread among white evangelicals than most other blocs of Americans. Forty percent of white evangelical Protestants said they were not likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19.[212]

Countermeasures

Vaccine hesitancy is challenging and optimal strategies for approaching it remain uncertain.[213][23]

Multicomponent initiatives which include targeting undervaccinated populations, improving the convenience of and access to vaccines, educational initiatives, and mandates may improve vaccination uptake.[214][215]

The World Health Organization (WHO) published a paper in 2016 intending to aid experts on how to respond to vaccine deniers in public. The WHO recommends for experts to view the general public as their target audience rather than the vaccine denier when debating in a public forum. The WHO also suggests for experts to make unmasking the techniques that the vaccine denier uses to spread misinformation as the goal of the conversation. The WHO asserts that this will make the public audience more resilient against anti-vaccine tactics.[216]

Providing information

Many interventions designed to address vaccine hesitancy have been based on the information deficit model.[57] This model assumes that vaccine hesitancy is due to a person lacking the necessary information and attempts to provide them with that information to solve the problem.[57] Despite many educational interventions attempting this approach, ample evidence indicates providing more information is often ineffective in changing a vaccine-hesitant person's views and may, in fact, have the opposite of the intended effect and reinforce their misconceptions.[32][57]

It is unclear whether interventions intended to educate parents about vaccines improve the rate of vaccination.[214] It is also unclear whether citing the reasons of benefit to others and herd immunity improves parents' willingness to vaccinate their children.[214] In one trial, an educational intervention designed to dispel common misconceptions about the influenza vaccine decreased parents' false beliefs about the vaccines but did not improve uptake of the influenza vaccine.[214] In fact, parents with significant concerns about adverse effects from the vaccine were less likely to vaccinate their children with the influenza vaccine after receiving this education.[214]

Communication strategies

Several communication strategies are recommended for use when interacting with vaccine-hesitant parents. These include establishing honest and respectful dialogue; acknowledging the risks of a vaccine but balancing them against the risk of disease; referring parents to reputable sources of vaccine information; and maintaining ongoing conversations with vaccine-hesitant families.[2] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends healthcare providers directly address parental concerns about vaccines when questioned about their efficacy and safety.[135] Additional recommendations include asking permission to share information; maintaining a conversational tone (as opposed to lecturing); not spending excessive amounts of time debunking specific myths (this may have the opposite effect of strengthening the myth in the person's mind); focusing on the facts and simply identifying the myth as false; and keeping information as simple as possible (if the myth seems simpler than the truth, it may be easier for people to accept the simple myth).[57] Storytelling and anecdote (e.g., about the decision to vaccinate one's own children) can be powerful communication tools for conversations about the value of vaccination.[57] A New Zealand-based General Practitioner has used a comic, Jenny & the Eddies, both to educate children about vaccines and address his patients' concerns through open, trusting, and non-threatening conversations, concluding [that] "I always listen to what people have to say on any matter. That includes vaccine hesitancy. That's a very important opening stage to improving the therapeutic relationship. If I'm going to change anyone's attitude, first I need to listen to them and be open-minded."[217] The perceived strength of the recommendation, when provided by a healthcare provider, also seems to influence uptake, with recommendations that are perceived to be stronger resulting in higher vaccination rates than perceived weaker recommendations.[32]

Provider presumption and persistence

Limited evidence suggests that a more paternalistic or presumptive approach ("Your son needs three shots today.") is more likely to result in patient acceptance of vaccines during a clinic visit than a participatory approach ("What do you want to do about shots?") but decreases patient satisfaction with the visit.[214] A presumptive approach helps to establish that this is the normative choice.[57] Similarly, one study found that the way in which physicians respond to parental vaccine resistance is important.[2] Nearly half of initially vaccine-resistant parents accepted vaccinations if physicians persisted in their initial recommendation.[57] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released resources to aid healthcare providers in having more effective conversations with parents about vaccinations.[218]

Pain mitigation for children

Parents may be hesitant to have their children vaccinated due to concerns about the pain of vaccination. Several strategies can be used to reduce the child's pain.[135] Such strategies include distraction techniques (pinwheels); deep breathing techniques; breastfeeding the child; giving the child sweet-tasting solutions; quickly administering the vaccine without aspirating; keeping the child upright; providing tactile stimulation; applying numbing agents to the skin; and saving the most painful vaccine for last.[135] As above, the number of vaccines offered in a particular encounter is related to the likelihood of parental vaccine refusal (the more vaccines offered, the higher the likelihood of vaccine deferral).[2] The use of combination vaccines to protect against more diseases but with fewer injections may provide reassurance to parents.[2] Similarly, reframing the conversation with less emphasis on the number of diseases the healthcare provider is immunizing against (e.g., "we will do two injections (combined vaccinations) and an oral vaccine") may be more acceptable to parents than "we're going to vaccinate against seven diseases".[2]

Cultural sensitivity

Cultural sensitivity is important to reducing vaccine hesitancy. For example, pollster Frank Luntz discovered that for conservative Americans, family is by far the "most powerful motivator" to get a vaccine (over country, economy, community, or friends).[219] Luntz "also found a very pronounced preference for the word 'vaccine' over 'jab.'"[219]

Avoiding online misinformation

It is recommended that healthcare providers advise parents against performing their own web search queries since many websites on the Internet contain significant misinformation.[2] Many parents perform their own research online and are often confused, frustrated, and unsure of which sources of information are trustworthy.[57] Additional recommendations include introducing parents to the importance of vaccination as far in advance of the initial well-child visit as possible; presenting parents with vaccine safety information while in their pediatrician's waiting room; and using prenatal open houses and postpartum maternity ward visits as opportunities to vaccinate.[2]

Internet advertising, especially on social networking websites, is purchased by both public health authorities and anti-vaccination groups. In the United States, the majority of anti-vaccine Facebook advertising in December 2018 and February 2019 had been paid for one of two groups: Children's Health Defense and Stop Mandatory Vaccination. The ads targeted women and young couples and generally highlighted the alleged risks of vaccines, while asking for donations. Several anti-vaccination advertising campaigns also targeted areas where measles outbreaks were underway during this period. The impact of Facebook's subsequent advertising policy changes has not been studied.[220][221]

Incentive programs

Several countries have implemented programs to counter vaccine hesitancy, including raffles, lotteries, rewards and mandates.[222][223][224][225] In the US State of Washington, authorities have given the green light to licensed cannabis dispensaries to offer free joints as incentives to get COVID-19 vaccination in an effort dubbed "Joints for Jabs".[226]

Vaccine mandates

Mandatory vaccination is one set of policy measures to address vaccine hesitancy by imposing penalties or burdens on those who fail to vaccinate. An example of this kind of measure is Australia's vaccine mandates around childhood vaccination, the No Jab No Pay policy. This policy linked financial payments to children's vaccine status and, while studies have found significant improvements in vaccination compliance, years later there were still issues of vaccine hesitancy.[227][228] In 2021, Australian airline Qantas issued plans to mandate COVID-19 vaccination for their work force.[229]

Geographical distribution

Vaccine hesitancy is becoming an increasing concern, particularly in industrialized nations. For example, one study surveying parents in Europe found that 12–28% of surveyed parents expressed doubts about vaccinating their children.[230] Several studies have assessed socioeconomic and cultural factors associated with vaccine hesitancy. Both high and low socioeconomic status as well as high and low education levels have all been associated with vaccine hesitancy in different populations.[135][231][232][233][234][235][236] Other studies examining various populations around the world in different countries found that both high and low socioeconomic status are associated with vaccine hesitancy.[3]

Migrant populations

Migrants and refugees arriving and living in Europe face various difficulties in getting vaccinated and many of them are not fully vaccinated. People arriving from Africa, Eastern Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Asia are more likely to be under-vaccinated (partial or delayed vaccination). Also, recently arrived refugees, migrants and seekers of asylum were less likely to be fully vaccinated than other people from the same groups. Those with little contact to healthcare services, no citizenship and lower income are also more likely to be under-vaccinated.[237][238]

Vaccination barriers for migrants include language/literacy barriers, lack of understanding of the need for or their entitlement to vaccines, concerns about the side-effects, health professionals lack of knowledge of vaccination guidelines for migrants, and practical/legal issues, for example, having no fixed address. Vaccines uptake of migrants can be increased by customised communications, clear policies, community-guided interventions (such as vaccine advocates), and vaccine offers in local accessible settings.[237][238]

Australia

An Australian study that examined the factors associated with vaccine attitudes and uptake separately found that under-vaccination correlated with lower socioeconomic status but not with negative attitudes towards vaccines. The researchers suggested that practical barriers are more likely to explain under-vaccination among individuals with lower socioeconomic status.[233] A 2012 Australian study found that 52% of parents had concerns about the safety of vaccines.[239]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy reportedly was spreading in remote Indigenous communities, where people are typically poorer and less educated.[240]

Europe

Confidence in vaccines varies over place and time and among different vaccines. The Vaccine Confidence Project in 2016 found that confidence was lower in Europe than in the rest of the world. Refusal of the MMR vaccine has increased in twelve European states since 2010. The project published a report in 2018 assessing vaccine hesitancy among the public in all the 28 EU member states and among general practitioners in ten of them. Younger adults in the survey had less confidence than older people. Confidence had risen in France, Greece, Italy, and Slovenia since 2015 but had fallen in the Czech Republic, Finland, Poland, and Sweden. 36% of the GPs surveyed in the Czech Republic and 25% of those in Slovakia did not agree that the MMR vaccine was safe. Most of the GPs did not recommend the seasonal influenza vaccine. Confidence in the population correlated with confidence among GPs.[241]

Policy implications

Multiple major medical societies including the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Medical Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics support the elimination of all nonmedical exemptions for childhood vaccines.[135]

Individual liberty

Compulsory vaccination policies have been controversial as long as they have existed, with opponents of mandatory vaccinations arguing that governments should not infringe on an individual's freedom to make medical decisions for themselves or their children, while proponents of compulsory vaccination cite the well-documented public health benefits of vaccination.[12][242] Others argue that, for compulsory vaccination to effectively prevent disease, there must be not only available vaccines and a population willing to immunize, but also sufficient ability to decline vaccination on grounds of personal belief.[243]

Vaccination policy involves complicated ethical issues, as unvaccinated individuals are more likely to contract and spread disease to people with weaker immune systems, such as young children and the elderly, and to other individuals in whom the vaccine has not been effective. However, mandatory vaccination policies raise ethical issues regarding parental rights and informed consent.[244]

In the United States, vaccinations are not truly compulsory, but they are typically required in order for children to attend public schools. As of January 2021, five states – Mississippi, West Virginia, California, Maine, and New York – have eliminated religious and philosophical exemptions to required school immunizations.[245]

Children's rights

Medical ethicist Arthur Caplan argues that children have a right to the best available medical care, including vaccines, regardless of parental feelings toward vaccines, saying "Arguments about medical freedom and choice are at odds with the human and constitutional rights of children. When parents won't protect them, governments must."[246][247]

A review of American court cases from 1905 to 2016 found that, of the nine courts that have heard cases regarding whether not vaccinating a child constitutes neglect, seven have held vaccine refusal to be a form of child neglect.[248]

To prevent the spread of disease by unvaccinated individuals, some schools and doctors' surgeries have prohibited unvaccinated children from being enrolled, even where not required by law.[249][250] Refusal of doctors to treat unvaccinated children may cause harm to both the child and public health, and may be considered unethical, if the parents are unable to find another healthcare provider for the child.[251] Opinion on this is divided, with the largest professional association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, saying that exclusion of unvaccinated children may be an option under narrowly defined circumstances.[135]

History

Variolation

Early attempts to prevent smallpox involved deliberate inoculation with the milder form of the disease (Variola Minor) in the expectation that a mild case would confer immunity and avoid Variola Major. Originally called inoculation, this technique was later called variolation to avoid confusion with cowpox inoculation (vaccination) when that was introduced by Edward Jenner. Although variolation had a long history in China and India, it was first used in North America and England in 1721. Reverend Cotton Mather introduced variolation to Boston, Massachusetts, during the 1721 smallpox epidemic.[252] Despite strong opposition in the community,[198] Mather convinced Zabdiel Boylston to try it. Boylston first experimented on his 6-year-old son, his slave, and his slave's son; each subject contracted the disease and was sick for several days until the sickness vanished and they were "no longer gravely ill".[252] Boylston went on to variolate thousands of Massachusetts residents, and many places were named for him in gratitude as a result. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu introduced variolation to England. She had seen it used in Turkey and, in 1718, had her son successfully variolated in Constantinople under the supervision of Charles Maitland. When she returned to England in 1721, she had her daughter variolated by Maitland. This aroused considerable interest, and Sir Hans Sloane organized the variolation of some inmates in Newgate Prison. These were successful, and after a further short trial in 1722, two daughters of Caroline of Ansbach Princess of Wales were variolated without mishap. With this royal approval, the procedure became common when smallpox epidemics threatened.[253]

Religious arguments against inoculation were soon advanced. For example, in a 1722 sermon entitled "The Dangerous and Sinful Practice of Inoculation", the English theologian Reverend Edmund Massey argued that diseases are sent by God to punish sin and that any attempt to prevent smallpox via inoculation is a "diabolical operation".[198] It was customary at the time for popular preachers to publish sermons, which reached a wide audience. This was the case with Massey, whose sermon reached North America, where there was early religious opposition, particularly by John Williams. A greater source of opposition there was William Douglass, a medical graduate of Edinburgh University and a Fellow of the Royal Society, who had settled in Boston.[253]: 114–22

Smallpox vaccination

After Edward Jenner introduced the smallpox vaccine in 1798, variolation declined and was banned in some countries.[254][255] As with variolation, there was some religious opposition to vaccination, although this was balanced to some extent by support from clergymen, such as Reverend Robert Ferryman, a friend of Jenner's, and Rowland Hill,[253]: 221 who not only preached in its favour but also performed vaccination themselves. There was also opposition from some variolators who saw the loss of a lucrative monopoly. William Rowley published illustrations of deformities allegedly produced by vaccination, lampooned in James Gillray's famous caricature depicted on this page, and Benjamin Moseley likened cowpox to syphilis, starting a controversy that would last into the 20th century.[253]: 203–05

There was legitimate concern from supporters of vaccination about its safety and efficacy, but this was overshadowed by general condemnation, particularly when legislation started to introduce compulsory vaccination. The reason for this was that vaccination was introduced before laboratory methods were developed to control its production and account for its failures.[256] Vaccine was maintained initially through arm-to-arm transfer and later through production on the skin of animals, and bacteriological sterility was impossible. Further, identification methods for potential pathogens were not available until the late 19th to early 20th century. Diseases later shown to be caused by contaminated vaccine included erysipelas, tuberculosis, tetanus, and syphilis. This last, though rare – estimated at 750 cases in 100 million vaccinations[257] – attracted particular attention. Much later, Charles Creighton, a leading medical opponent of vaccination, claimed that the vaccine itself was a cause of syphilis and devoted a book to the subject.[258] As cases of smallpox started to occur in those who had been vaccinated earlier, supporters of vaccination pointed out that these were usually very mild and occurred years after the vaccination. In turn, opponents of vaccination pointed out that this contradicted Jenner's belief that vaccination conferred complete protection.[256]: 17–21 The views of opponents of vaccination that it was both dangerous and ineffective led to the development of determined anti-vaccination movements in England when legislation was introduced to make vaccination compulsory.[259]

England

Because of its greater risks, variolation was banned in England by the Vaccination Act 1840 (3 & 4 Vict. c. 29), which also introduced free voluntary vaccination for infants. Thereafter Parliament passed successive acts to enact and enforce compulsory vaccination.[260] The Vaccination Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict. c. 100) introduced compulsory vaccination, with fines for non-compliance and imprisonment for non-payment. The Vaccination Act 1867 (30 & 31 Vict. c. 84) extended the age requirement to 14 years and introduced repeated fines for repeated refusal for the same child. Initially, vaccination regulations were organised by the local Poor Law Guardians, and in towns where there was strong opposition to vaccination, sympathetic guardians were elected who did not pursue prosecutions. This was changed by the Vaccination Act 1871 (34 & 35 Vict. c. 98), which required guardians to act. This significantly changed the relationship between the government and the public, and organized protests increased.[260] In Keighley, Yorkshire, in 1876 the guardians were arrested and briefly imprisoned in York Castle, prompting large demonstrations in support of the "Keighley Seven".[259]: 108–09 The protest movements crossed social boundaries. The financial burden of fines fell hardest on the working class, who would provide the largest numbers at public demonstrations.[261] Societies and publications were organized by the middle classes, and support came from celebrities such as George Bernard Shaw and Alfred Russel Wallace, doctors such as Charles Creighton and Edgar Crookshank, and parliamentarians such as Jacob Bright and James Allanson Picton.[260] By 1885, with over 3,000 prosecutions pending in Leicester, a mass rally there was attended by over 20,000 protesters.[262]

Under increasing pressure, the government appointed a Royal Commission on Vaccination in 1889, which issued six reports between 1892 and 1896, with a detailed summary in 1898.[263] Its recommendations were incorporated into the Vaccination Act 1898 (61 & 62 Vict. c. 49), which still required compulsory vaccination but allowed exemption on the grounds of conscientious objection on presentation of a certificate signed by two magistrates.[12][260] These were not easy to obtain in towns where magistrates supported compulsory vaccination, and after continued protests, a further act in 1907 allowed exemption on a simple signed declaration.[262] Although this solved the immediate problem, the compulsory vaccination acts remained legally enforceable, and determined opponents lobbied for their repeal. No Compulsory Vaccination was one of the demands of the 1900 Labour Party General Election Manifesto.[264] This was done as a matter of routine when the National Health Service was introduced in 1948, with "almost negligible" opposition from supporters of compulsory vaccination.[265]

Vaccination in Wales was covered by English legislation, but the Scottish legal system was separate. Vaccination was not made compulsory there until 1863, and a conscientious objection was allowed after vigorous protest only in 1907.[256]: 10–11

In the late 19th century, Leicester in the UK received much attention because of how smallpox was managed there. There was particularly strong opposition to compulsory vaccination, and medical authorities had to work within this framework. They developed a system that did not use vaccination but was based on the notification of cases, the strict isolation of patients and contacts, and the provision of isolation hospitals.[266] This proved successful but required acceptance of compulsory isolation rather than vaccination. C. Killick Millard, initially, a supporter of compulsory vaccination was appointed Medical Officer of Health in 1901. He moderated his views on compulsion but encouraged contacts and his staff to accept vaccination. This approach, developed initially due to overwhelming opposition to government policy, became known as the Leicester Method.[265][267] In time it became generally accepted as the most appropriate way to deal with smallpox outbreaks and was listed as one of the "important events in the history of smallpox control" by those most involved in the World Health Organization's successful Smallpox Eradication Campaign. The final stages of the campaign generally referred to as "surveillance containment", owed much to the Leicester method.[268][269]

United States

In the US, President Thomas Jefferson took a close interest in vaccination, alongside Benjamin Waterhouse, chief physician at Boston. Jefferson encouraged the development of ways to transport vaccine material through the Southern states, which included measures to avoid damage by heat, a leading cause of ineffective batches. Smallpox outbreaks were contained by the latter half of the 19th century, a development widely attributed to the vaccination of a large portion of the population. Vaccination rates fell after this decline in smallpox cases, and the disease again became epidemic in the late 19th century.[270]

After an 1879 visit to New York by prominent British anti-vaccinationist William Tebb, The Anti-Vaccination Society of America was founded.[271][272] The New England Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League formed in 1882, and the Anti-Vaccination League of New York City in 1885.[272] Tactics in the US largely followed those used in England.[273] Vaccination in the US was regulated by individual states, in which there followed a progression of compulsion, opposition, and repeal similar to that in England.[274] Although generally organized on a state-by-state basis, the vaccination controversy reached the US Supreme Court in 1905. There, in the case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the court ruled that states have the authority to require vaccination against smallpox during a smallpox epidemic.[275]