Wallack's Theatre

Three New York City playhouses named Wallack's Theatre played an important part in the history of American theater as the successive homes of the stock company managed by actors James W. Wallack and his son, Lester Wallack. During its 35-year lifetime, from 1852 to 1887, that company developed and held a reputation as the best theater company in the country.

Each theater operated under other names and managers after (and in one case before) the Wallack company's tenure. All three are demolished.

485 Broadway

[edit]| As of | Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| December 23, 1850 | Brougham's Lyceum | Ireland:584 |

| September 8, 1852 | Wallack's Lyceum | Wallack:13–14 |

| November 1, 1852 | Wallack's Theatre | The New York Times, November 1, 1852 |

| May 22, 1861 | The Broadway Music Hall | Brown v1:508 |

| March 1, 1862 | The New York Athenæum | Brown v1:509 |

| March 17, 1862 | Mary Provost's Theatre | Brown v1:509 |

| April 21, 1862 | George L. Fox's Olympic Theatre | Brown v1:510 |

| June 26, 1862 | Mary Provost's Theatre | Brown v1:511 |

| The New Idea | Brown v1:511 | |

| September 15, 1862 | The German Opera House | Brown v1:511 |

| September 7, 1863 | The New York Theatre | Brown v1:511 |

| November 10, 1863 | The Broadway Amphitheatre | Brown v1:511 |

| May 2, 1864 | The Broadway Theatre | Brown v1:512 |

| April 28, 1869 | [last performance] | Brown v1:523 |

James W. Wallack and Lester Wallack, father and son, were 19th century actors and theater managers; that is, entrepreneurs whose business was a theatrical stock company, a troupe of actors and support personnel presenting a variety of plays in one theater.[2] Actor-managers, such as the Wallacks, were members of their own company. Often, a manager leased a theater from its owner, and since the building was deemed an important part of the playgoer's experience, typically renovated it to his own taste. Sometimes a manager was able to have a theater built to his specifications, as did Irish-American actor and dramatist John Brougham.

Brougham's Lyceum, 1850–52

[edit]On December 23, 1850, John Brougham opened his Lyceum at 485 Broadway[3] near Broome Street. The next day, the New York Herald reported:

This new temple of Thespis was opened last evening, before a brilliant and crowded audience, with an éclat which prognosticates its future career to be triumphant. ... [It] is capable of containing about 1,800 or 2,000 persons. ... The whole presents a very pretty little theatre. ... Mr. Trimble, the well-known builder, has added another 'story' to his architectural fame. ... The opening entertainments commenced with a humorous and appropriate address, entitled 'Brougham and Co.,' in which the whole company were introduced. ... The performances concluded with the laughable interlude of Deeds of Dreadful Note, and a new piece, called The Light Guard, or Woman's Rights.[4][5]

Builder and architect John M. Trimble, a theater specialist, had rebuilt the Bowery Theatre in 1845 after its destruction by fire, and had designed the Broadway Theatre, between Pearl and Anthony (now Worth) Streets in 1847. Earlier in 1850, he had built the new "Lecture Room" (theater) of Barnum's American Museum, and Tripler Hall (a concert venue).

The performances at the new theater were principally burlesques and farces.

Wallack's Theatre, 1852–61

[edit]1852–56

[edit]Brougham was a successful actor, but this enterprise failed. After two seasons, James W. Wallack leased the house and, following custom, renamed it for himself.[6] Aged 57, he was a well-known and well-respected British American actor who had proved himself as a manager at the National Theater (Church and Leonard Streets) from 1837 until it burned down in 1839.[7][8] After extensive renovation, he opened his new theater on September 8, 1852, with The Way to Get Married and The Boarding School.[9] His sons, Lester, age 32, and Charles, were stage-manager and treasurer, respectively.[10] Theodore Moss, who was to become a lifelong associate of the Wallacks, was assistant treasurer and later became treasurer, his position for many years. Admissions were fifty and twenty-five cents.[11]

The elder Wallack had made his first appearance in America at age 24, on September 7, 1818, playing Macbeth at the Park Theatre to much acclaim.[12] Lester's first appearance in the United States had been made, also to much acclaim, at age 27 on opening night of the aforementioned Broadway Theatre, September 27, 1847, playing Sir Charles Coldstream in the afterpiece, Dion Boucicault's and Charles Mathews' farce Used Up. (His stage name was John Lester; he didn't work as Lester Wallack until October 1858.)[13]

In 1854, Putnam's Monthly commented:

There are two theatres in New York, and but two which are devoted exclusively to the performance of the regular drama; these are Burton's in Chambers Street, and Wallack's in Broadway. ... Wallack's Lyceum, in Broadway, is an exceedingly elegant little house, the style of the interior decoration is in excellent taste, and the effect of a full house is light, cheerful, exhilarating, and brilliant. ... Great attention is always paid to the production of pieces at this brilliant little house, and the costumes and scenery form an important part of the attraction. English comedy and domestic dramas form the chief attractions at Wallack's, and the house is generally full. The utmost order and decorum are maintained ... and everything offensive to the most delicate taste carefully excluded from the stage.[14]

Charlotte Thompson made her theatrical debut at Wallack's in 1854.[15] In 1855, Wallack engaged the actress Mary Gannon, who had a series of critical triumphs in comedies with Wallack's company over the next decade, including performances in James Sheridan Knowles's The Love Chase, Octave Feuillet's The Romance of a Poor Young Man, Knights of the Round Table, Elizabeth Inchbald's To Marry or Not to Marry, and Augustus Glossop Harris's The Little Treasure, among others.[16]

1856–61

[edit]For the two seasons 1856–58 Wallack leased the house to William Stuart, who managed it with Lester Wallack as stage manager, Dion Boucicault as general director, and Theodore Moss as treasurer. Stuart, an Irishman whose real name was Edmund O'Flaherty, had been a Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom. An alleged embezzler, he fled to New York in 1854, and wrote for the New York Tribune. He later managed the Winter Garden, and then the New Park Theatre, on Broadway between 21st and 22nd Streets, and was widely popular socially.[17]

The elder Wallack performed October 20 through November 22, 1856, and May 11 through June 6, 1857. Brown asserts that Wallack's engagement was unsuccessful, that he played to the poorest houses of the season, and that he insisted on appearing in parts for which at this time he was too old, though he had gained a reputation in them twenty years before. Wallack did not perform during the 1857–58 season, and he resumed management of the theater in fall 1858. He appeared for the first time that season on December 9, as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice; on January 17 created the part of Colonel Delmar in The Veteran, Lester's new play, which ran 102 nights; and ended his acting career on May 14, as Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing. He managed the house for two more seasons.[18][19]

Ireland's assessment (published in 1867):

The establishment heretofore known as Brougham's Lyceum, which during the [1851–52] season had ceased to attract any share of public attention, [in 1852] passed into the hands of James W. Wallack, who, with [his department heads], soon succeeded not only in rivaling, but in a measure superseding Burton's Theatre in public esteem. The hand of a master was visible in every production, and the taste, elegance, and propriety displayed about the whole establishment gave it a position of respectability never hitherto enjoyed in New York, except at the old Park Theatre.[20]

After Wallack, 1861–69

[edit]In 1861, Wallack moved his company. After he left number 485, the theater was continued under various managers and names and underwent various vicissitudes — German opera, melodrama, legitimate theatre, concerts, Lent's Circus — until 1864, when it came under the management of George Wood, who restored its pre-circus condition and opened it May 2 as the Broadway Theatre.[21] On April 1, 1867, Wood transferred the lease to Barney Williams, who managed the house for its last two years. The final performance was a benefit for Williams' business manager on Wednesday, April 28, 1869, comprising Ireland as It Was, the farces The Returned Volunteer and Game of Tag, two dance numbers, and performers with velocipedes. The Broadway Theatre was soon torn down and replaced by the extant (in 2013) building comprising a store and lofts.[22]

844 Broadway at 13th Street

[edit]| As of | Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| September 25, 1861 | Wallack's Theatre | Brown v2:245 |

| September 15, 1881 | The Germania Theatre | Brown v2:303 |

| March 26, 1883 | The Star Theatre | Brown v2:303 |

| April 20, 1901 | [last performance] | The New York Times, April 21, 1901[23] |

Wallack's Theatre, 1861–81

[edit]As the city grew northward, James Wallack sought to follow. So did William Gibson, a glass stainer and supplier of architectural ornament, who by 1860 had acquired land on the northeast corner of Broadway and 13th Street[24] for a new home for his business (and himself). Gibson was persuaded to include in his development a new home for Wallack's company as well.[25]

Sketches for the interior of the theater were begun by Trimble, the last he ever made: the work and his career were ended by blindness. The design was carried out by his student Thomas R. Jackson.[26]

For something more than twenty years [writes Brown] the most famous theatre in the United States was that of James W. Wallack, situated on the northeast corner of Broadway and Thirteenth Street. ... It was in this house the name of Wallack won its proudest laurels. [James] W. Wallack was its first manager, but he never played there, and to all intents and purposes J. Lester Wallack, with Theodore Moss in the business department, was from the first head and front of the theatre. ... The initial program was The New President, by Tom Taylor, September 25, 1861.[27]

The first season closed June 9, 1862, with a benefit to Theodore Moss.[28] The New York Times wrote:

The last night at Wallack's was an appropriate climax to nine months of brilliantly successful management. ... The entertainment offered on [Moss'] behalf on Monday was, in our opinion, the very best that had been advertised anywhere for a twelve-month. The Little Treasure and Rural Felicity were given, and between the pieces Mr. Wallack—the Veteran himself—delivered his annual speech.[29]

It was his last appearance on any stage; he died Christmas Day, 1864.[30][31]

In 1869, Junius Henri Browne wrote:

Wallack's is, and has been for years, the best theater in the United States, and is quite as good as any in Europe outside of Paris. It is devoted almost entirely to comedy, and has no 'stars,' as that term is usually employed, but the most capable and best-trained company that can be selected at home or abroad. Plays without any particular merit succeed, because they are so carefully put upon the stage, so fitly costumed and so conscientiously enacted. ... The old stage traditions and time-honored conventionalisms are given up there. Mouthing, ranting, and attitudinizing are not in vogue; and men and women appear and act as such, and represent art instead of artificiality. It is commonly said that New-York goes to Wallack's; and so it does more than to any other place of amusement. But lovers of good acting from every section usually avail themselves of a sojourn in the city to witness the artistic representations at that theater.[32]

Among the actors were, at various times, Charles Fisher, John Gilbert, James Williamson, J. W. Wallack Jr., E. L. Davenport, J. H. Stoddart, Charles Mathews, E. M. Holland, Steele Mackaye, Charles Coghlan, Harry Edwards, Madame Ponisi, Mary Gannon, Mrs. John Hoey, Rose Eytinge, Effie Germon, Jeffreys Lewis, Ada Dyas, Stella Boniface, and Madeline Henriques.[33]

According to Brown, some of the notable performances in the 1860s, not only on account of their artistic quality, but on account of the large receipts, were The Poor Gentleman, The Provoked Husband, She Stoops to Conquer, Still Waters Run Deep, The School for Scandal, Captain of the Watch, Central Park, The Belle's Stratagem, and The Rivals.

But the great run of those days was made by Rosedale, in which Lester Wallack was a singularly graceful, handsome, and attractive hero. The rôle fitted him admirably. The play ran in 1863 for 125 nights, something almost unprecedented. ... The most phenomenal run at the house occurred during the following decade, when Dion Boucicault produced The Shaughraun, which had 143 performances."[34]

In 1871 Lester Wallack brought the English scenic designer Joseph Clare to New York to become his company's resident designer. Theatre historian Gerald Bordman stated that Clare's work for Wallack gained Clare "the reputation of possibly the finest set designer in America, with his settings admired for their elegance and proper sense of period".[35]

Germania Theatre, 1881–83

[edit]By 1881, shrinking audiences prompted Wallack to seek, once again, a new location farther north, where most of the theaters were located by that time. In February, he leased the corner of 30th Street and Broadway and agreed to sell his lease on number 844 to Adolph Neuendorff, the conductor-composer whose German-language Germania Theatre company had been playing in Tammany Hall since 1873.[36] On July 2, Wallack's company closed its last season at the old house with The World. On September 15 Neuendorff opened at 844, renamed Germania Theatre, with a festive program, but the move proved disastrous. By early 1883, he was bankrupt, and sold the theater back to Lester Wallack, who renamed it the Star Theatre and reopened it on March 26 with an engagement by a company headed by Boucicault presenting several of his plays.[37]

Star Theatre, 1883–1901

[edit]1883–87

[edit]That summer Wallack announced the house would be devoted to touring companies exclusively; it was extensively redecorated and the stage rebuilt with traps and built-in platforms. The new season opened August 27 with Lawrence Barrett's production of Francesca da Rimini, by George H. Boker. Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre stock company of London (whose leading lady was Ellen Terry) opened its first American tour at the Star on October 29. The New York Times published an investigation of ticket speculation, a subject of public complaint, and its connection to theater managements, beginning December 13, with an article spotlighting the Star Theatre and Theodore Moss.[38] Edwin Booth appeared for a month in December and January.

Over the next several years, there appeared such stars as Joseph Jefferson, E. H. Sothern, Fanny Janauschek, John Edward McCullough, Johnston Forbes–Robertson, William E. Sheridan, Helena Modjeska, Maurice Barrymore, Anna Judic, Fanny Davenport, Henry Miller, Frederick Mitterwurzer (a German star, supported by a German-language company), Mr.and Mrs. William J. Florence, Stuart Robson, William H. Crane, Mary Anderson, Sarah Bernhardt, and Wilson Barrett, many of whom had multiple engagements, as did Boucicault, Lawrence Barrett, Irving, and Booth. The McCaull Comic Opera Company had a multi-week run in 1885–86 and another in 1886–87.[39]

1887–95

[edit]On August 22, 1887, the house opened under the management of Henry E. Abbey, John B. Schoeffel,[40] and Maurice Grau[41] as Abbey, Schoeffel and Grau, who were primarily importers of European companies and stars to tour North America; they also managed the Metropolitan Opera House in its first season (1883–84) and again subsequently. Johnson and Slavin's minstrels, Hedwig Raabe (a German actress with a German-language company), magician Alexander Herrmann, and Brockmann's Monkey Theatre Company[42] appeared, plus Irving, Jefferson, Julia Marlowe, and the Florences.

During the summer of 1888, the interior was largely redesigned and reconstructed to improve sightlines and add seats. On August 27, 1888, the theater opened with Theodore Moss as proprietor and Charles Burnham as manager.[43] Johnson & Slavin's minstrels, Lydia Thompson, John W. Albaugh, Henry E. Dixey, Annie Pixley, Marie Wainwright, Fanny Davenport, John Wild,[44] Benoît–Constant Coquelin, Rose Coghlan, and Robson and Crane appeared, and attractions included Boston's Howard Athenaeum Specialty Company and The Crystal Slipper from the Chicago Opera House.[45]

During the summer of 1889, the stage was removed and a "section stage" was constructed. The roof was raised 25 feet, so that the heaviest scenery could be drawn up out of sight without folding it. Electric lights were introduced in the auditorium and on the stage, though the gas was retained for use in emergencies, or in producing stage effects in which it might be superior to the electric light. New ventilation equipment was installed. The entire orchestra floor was reconstructed; the circle which had been added to this part of the auditorium the previous summer was removed. The boxes were rearranged, and the original iron fronts of the balcony and gallery were replaced by papier-mâché and woodwork. The capacity was 1,573.[46]

For the next six seasons (1889–95) Theodore Moss managed the theater himself. His biggest star was comedian William H. Crane, whose hits included For Money, On Probation, The Pacific Mail, The Player, and, especially, The Senator.

During the summer of 1890, a new cooling system was installed, with an electric-powered Sturtevant blower forcing 20,000 cubic feet of air a minute over two tons of ice in a basement tank, and then through ducts to registers under the main-floor aisles. Wall fans circulated the air. A huge sponge, saturated with perfume, was placed at the mouth of the principal air duct.[47]

1895–1901

[edit]By 1895, the city's first-class theaters had reached the West 40's. In May, Moss announced that he was repositioning his 13th Street theater as a "popular-priced" house, but he immediately changed course, selling his interest, which comprised leases he held on the ground and building.[48]

The purchaser was Neil Burgess, a comedian who was best known for his perennial hit, The County Fair, with its famous racing scene which featured real horses on treadmills. Burgess spent six months rebuilding the stage, electrical lighting system, and dressing rooms. On November 2, 1895, he opened in a new vehicle: The Year One, by Charles Barnard, which—despite a similar racing scene—was an irredeemable failure.[49] Early the next year he went on tour, leasing the theater as of January 27 to Walter Sanford, who soon subleased it to Jacob Litt, producer of melodramas.

The next season opened Saturday night, August 29, 1896, with low admission prices, under the management of R. M. Gulick & Co. (Gulick, Henry M. Bennett, William T. Keogh, and Thomas Davis), who also operated theaters in Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Boston, and who would manage the Star for its remaining five seasons (1896–1901). There was a new bill every Monday, except for occasional multi-week runs.[50]

Burgess went bankrupt and Moss reacquired the primary leases, which expired May 1, 1899, finally ending his association with the Star Theatre. In that year the ground owner, William Waldorf Astor, announced the projected redevelopment of the site, but the Gulick firm made a good enough offer that the plan was postponed and a provisional lease was granted to them, which in the event ran two years.[51]

On Saturday, April 20, 1901, with Thomas E. Shea starring in The Man-o'-War's Man, the Star Theatre closed forever. There was no ceremony.[52][53] A time-lapse film of the demolition, which began the same month, was made by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company from diagonally across Broadway; it was added to the National Film Registry in 2002.[54] The theater was replaced by an eight-story commercial structure, designed by Clinton & Russell, whose principal tenant was the clothier Rogers, Peet & Co.[55]

Today the entire block is occupied by a 1999 mixed-use building, with an entrance to a multiplex cinema on the Wallack's site.[56]

30th Street and Broadway

[edit]

Wallack's Theatre, 1881–88

[edit]1881–87

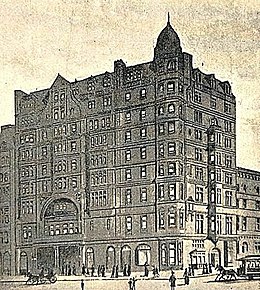

[edit]Ground was broken for Lester Wallack's new theater on the northeast corner of 30th Street and Broadway[57] May 21, 1881,[58] and on December 4, The New York Times reported:

The building, which is erected on ground leased for 21 years, with the privilege of two renewals of 21 years each, has frontage of 105 feet on Broadway and 122 feet on Thirtieth-street. In due course, a nine-story flat-house will rise above the theatre [never built], and shops will environ it. ... The main entrance is on Broadway and is 30 feet wide, the visitor passing under a portico resting on six polished red granite columns. There are, besides, two gallery entrances on Broadway, an entrance on Thirtieth-street, and stage entrances on Thirtieth-street and on Broadway. ... The parquet and balcony contain 800 seats. ... The gallery contains 450 most comfortable chairs. There are also eight boxes. ... Under the Broadway curbstone and the main entrance is a café. ... A magnificent chandelier of copper and brass, with a spread of 14 feet and 200 burners, depends from the dome, and smaller gas-fixtures spring from the painted panels on the walls and other points. Electric lights will be used outside the theatre, and the question of using them within was ... dismissed from immediate consideration. ... The architect is Mr. George A. Freeman Jr.[59]

| As of | Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| April 1, 1882 | Wallack's | Brown v3:310 |

| October 8, 1888 | Palmer's | Brown v3:331 |

| December 7, 1896 | Wallack's | Brown v3:355 |

| May 1, 1915 | [last performance] | The New York Times, May 2, 1915[60] |

George Albree Freeman (1859–1934),[61] born and raised in New York City, graduated in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He practiced in Stamford, Connecticut, mostly in the late 19th century, before removing to Sarasota, Florida, where he continued to practice.[62] He was a designer of the Seacroft House, with Bruce Price, in Sea Bright, New Jersey (1882)[63] and the Federal Building, with Harold N. Hall and Louis A. Simon, in Sarasota (1932);[61] expanded Stanford White's 1905 Lambs Club Building, 130 West 44th Street in New York City (1915);[64] and designed the Soldiers and Sailors' Monument in Stamford (1920).[62]

The new theater was dedicated January 4, 1882, "with a magnificent revival of The School for Scandal, which had an exceptionally fine cast" led by John Gilbert and Rose Coghlan. As in the past, the treasurer was Theodore Moss.[68]

Jenkins comments:

Here Wallack had an excellent stock company as before; but the house never became so famous or so popular as the old Thirteenth Street theatre—perhaps, because a new generation of theatre goers had grown up and the actor-manager was getting old.[69]

And losing his health. The Wallack stock company played six seasons at 30th Street and 35 altogether. The company ended its last home season on May 7, 1887, played a week in Brooklyn, and on May 16 went to Daly's Theatre, across the street, for a two-week run of The Romance of a Poor Young Man. On May 30 its engagement, and its existence, ended.[70] Wallack retired as a manager.

1887–88

[edit]The next season began October 11, 1887, with Lester Wallack as proprietor; Theodore Moss and the firm of Abbey, Schoeffel and Grau as lessees; Abbey as manager; and a stock company that included many of Wallack's former players.[71] It was unsuccessful and lasted only one season but went out in style, with eleven weeks of old Wallack hits directed by Wallack himself. Wallack's health did not permit him to act, or even attend the last performance on May 5, 1888: The School for Scandal, again starring Gilbert and Coghlan.[72] In July Abbey stepped down as manager and A. M. Palmer, well-respected as the manager of the stock companies at the Madison Square and (formerly) Union Square Theatres, took a ten-year lease, announcing that he would rename the house after himself.[73] The next season began October 11, 1887, with Lester Wallack as proprietor; Theodore Moss and the firm of Abbey, Schoeffel and Grau as lessees; Abbey as manager; and a stock company that included many of Wallack's former players.[71] It was unsuccessful and lasted only one season but went out in style, with eleven weeks of old Wallack hits directed by Wallack himself. Wallack's health did not permit him to act, or even attend the last performance on May 5, 1888: The School for Scandal, again starring Gilbert and Coghlan.[72] In July Abbey stepped down as manager and A. M. Palmer, well-respected as the manager of the stock companies at the Madison Square and (formerly) Union Square Theatres, took a ten-year lease, announcing that he would rename the house after himself.[73]

Lester Wallack died at his country home near Stamford, Connecticut, September 6, 1888, age 68.[74]

Palmer's Theatre, 1888–96

[edit]Palmer's Theatre[75] opened October 8, 1888, as a "combination house" (i. e., a theater for the presentation of combination companies), having been previously booked with the Abbey firm's attractions for most of the first season. Palmer's announced goal was to establish a stock company there, either by using players from his company at the smaller Madison Square Theatre, or by transferring the entire troupe. But although his actors performed occasional engagements at Palmer's, it remained a combination house.

Among the performers appearing at Palmer's Theatre were Benoît–Constant Coquelin and Jane Hading, Richard Mansfield, Rose Coghlan, Mary Anderson, Mrs. James Brown–Potter, Charles Wyndham, Tommaso Salvini, E. S. Willard, Marie Wainwright, John Drew (Jr.), Maude Adams, Annie Russell, Lillie Langtry, Julia Marlowe, and Georgia Cayvan.

The McCaull company played 30 weeks in 1889 and 17 in 1891. Comic operas were also given by the companies of Henry E. Dixey, Digby Bell, and Della Fox, among others. The biggest hit at Palmer's Theatre was the burlesque 1492 Up to Date, which played 29 weeks (not counting a summer hiatus, during which the show played the Garden Theatre) in 1893 and 1894.

By November 1896, Palmer was $31,000 in arrears to Moss, who threatened to sue. Instead, Palmer relinquished his lease two years early, on November 16. Moss restored the theater's original name on December 7.[76]

Wallack's Theatre, 1896–1915

[edit]For the next five years (1896–1901) Moss, with his son, Royal E. Moss, managed the theater as a combination house. Maurice Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore, Julia Arthur, Frank Daniels, William H. Crane, and Otis Skinner appeared, among many other stars. On May 16, 1898, the Royal Italian Grand Opera Company gave the New York premiere of Puccini's opera La bohème. In March 1900, police closed the theater and arrested Olga Nethersole, the star of Sapho; her manager, Marcus Mayer; the leading man, Hamilton Revelle; and Theodore Moss; for violating public decency by performing the play. They were tried and acquitted, and the show's run continued in April.[77]

Moss died July 13, 1901, at his country home in Sea Bright, New Jersey, just a few weeks after the Star Theatre's demolition. Moss' eldest daughter had married Lester Wallack's eldest son; another daughter was married to architect C. P. H. Gilbert. Unlike Lester Wallack, Moss died a wealthy man. His will left the entire estate to his wife Octavia, and requested that the name of Wallack's Theatre be retained.[78]

Octavia Moss became the manager of Wallack's Theatre, with active control in the hands of her son, Royal, and Charles Burnham continuing as business manager.[79]

In May 1902, Mrs. Moss renewed the ground lease.[80] Over the following years, the theater's hits included The Sultan of Sulu (1902–03),[81] a musical satire by George Ade with music by Alfred George Whathall; The County Chairman (1903–04)[82] by George Ade, starring Maclyn Arbuckle; The Sho-Gun (1904–05)[83] by George Ade with music by Gustav Luders; The Squaw Man (1905–06)[84] by Edwin Milton Royle, starring William Faversham and George Fawcett; The Rich Mr. Hoggenheimer (1906–07),[85] a musical farce with book and lyrics by Harry B. Smith and music by Ludwig Engländer, and starring Sam Bernard; A Knight for a Day (1907–08),[86] a musical comedy with book and lyrics by Robert B. Smith and music by Raymond Hubbell; Alias Jimmy Valentine (1910)[67] by Paul Armstrong, starring H. B. Warner and Laurette Taylor; Pomander Walk (1910–11)[87] by Louis N. Parker, starring George Giddens and Lennox Pawle; Disraeli (1911–12)[88] by Louis N. Parker, starring George Arliss; and Grumpy (1913–14),[89] a thriller by Horace Hodges and T. Wigney Percyval, starring Cyril Maude and Margery Maude.

Mrs. Moss died January 15, 1910.[90] Royal Moss, administrator of her estate, leased Wallack's Theatre to Charles Burnham.[91]

In January 1915, the Treblig Realty Company, comprising Mrs. Moss' heirs, sold the theater.[92] On January 27, English actor-manager Granville Barker and his troupe began a repertory season at Wallack's.[93] In March, plans were announced for a 12-story factory building to replace 29–33 West 30th Street – i. e., the stage and dressing rooms – curtailing Barker's run.[94]

The last performance at Wallack's 30th Street theater occurred on Saturday night, May 1, 1915, when Barker's company presented Androcles and the Lion and The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife. Following the plays, an epilogue written for the occasion by Oliver Herford was read by Rose Coghlan, the leading lady on opening night in 1882.[95]

Replacement

[edit]The new building opened in 1916. The rest of the theatre was turned into retail stores, until it was replaced in 1931 by an eight-story factory building, 1220 Broadway. Both are office buildings today.[96]

References

[edit]- ^ Number 481, with the sign "A. Roux," appears to be extant. See Google Street View.

- ^ Cort Theater (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 17, 1987. p. 2, last paragraph.

- ^ Perris (1853), Plate 30.

- ^ Jenkins:208

- ^ "Brougham's Theatre–The Opening Night" The New York Herald December 24, 1850, p. 1 col. 6

- ^ Wallack:145–47

- ^ Brown v1:243–54 and Florence:455 last sentence – 456

- ^ "Theatrical and Musical: Opening of the Lyceum Theatre—J. W. Wallack, Esq." The New York Herald (morning ed.). September 2, 1852. p. 7, column 4.

- ^ "Opening of Wallack's Lyceum". The New York Herald (morning ed.). September 9, 1852. p. 4, column 5.

- ^ Charles Wallack died in 1855 ("Death of Mr. Charles Wallack" The New York Times August 9, 1855 and "Died" The New York Times August 10, 1855 [first item]). Lester had two additional siblings, James and Henry, neither in theater (Florence:457).

- ^ Wallack:18, Jenkins:208, and Brown v1:477

- ^ Winter:300

- ^ Wallack:11-12, Winter:318, Brown v1:498, and "Amusements" The New York Times October 6, 1858 (scroll down to "Wallack's Theatre", which gives a review of the opening night naming "Mr. Lester Wallack").

- ^ Putnam's Monthly, Vol. 3, No. 14 (February 1854). G. P. Putnam & Co., New York:151.

- ^ Garrett, Thomas Ellwood (1863). Biographical Records of Charlotte Thompson: "the Hope of the American Stage". St. Louis: George Knapp & Co. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ James Fisher (2015). "Gannon, Mary (1829—1868)". Historical Dictionary of American Theater. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 188. ISBN 9780810878334.

- ^ Brown v1:489, 463; McCarthy:145–47; "Death of William Stuart" The New York Times December 29, 1886

- ^ Brown v1:492–93 and 497–99

- ^ Ireland:657–59

- ^ Ireland:610–11

- ^ The 1847 Broadway Theatre had closed permanently on April 2, 1859 (Ireland:682).

- ^ Jenkins:208. (See also Brown v1:511–12.) The present building at 483–485 Broadway was constructed between September 1, 1869 and March 31, 1870, according to: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, SoHo - Cast-Iron Historic District Designation Report (1973), p. 37.

- ^ "The Star Now a Memory" (PDF). The New York Times. April 21, 1901. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ See

- Star Theatre at Internet Broadway Database, which shows address as 844 Broadway

- Perris (1859), Plate 57, which shows address as 842–846.

- ^ "The New Theatre" The New York Times October 8, 1860

- ^ Phelps:329 and The New York Times October 8, 1860 (cited above): "For the lot, 150 by 75, which [Wallack] has taken on a lease of ten years, he pays Mr. Gibson an annual rent of $10,000 a year, and all taxes, the rent to commence from to-day. In addition, he is to pay $2,500 for the entrance on Broadway, for the first five years, and $3,500 for the remaining five. Mr. Wallack lodges with Mr. Gibson $5,000 as security for the erection of the building, which sum, on its completion, is to be allowed in the first payment of rent. The theatre is estimated to cost, in erection and fittings, etc., $30,000, and at the close of the ten years passes into Mr. Gibson's hands. Mr. Trimble is preparing the plan."

- ^ Brown v2:244–45

- ^ Brown v2:248

- ^ "Local Intelligence.; Amusements" The New York Times June 17, 1862

- ^ Jenkins:208–10

- ^ Brown v3:330

- ^ Browne, J. H.:179

- ^ Brown v2:245

- ^ Brown v2:302

- ^ Bordman, Gerald Martin (1987). "Clare, Joseph". The Concise Oxford Companion to American Theatre. Oxford University Press. p. 131.

- ^ Brown v3:81 and "The German Drama" The New York Times September 14, 1873 (scroll down). He was followed at that theater by Tony Pastor.

- ^ "A New Owner for Wallack's" The New York Times March 1, 1881; "New-York" The New York Times May 4, 1881, paragraph 13; "Amusements: Wallack's Theatre" The New York Times 1881-07-02; "Theatres Getting Ready" The New York Times August 7, 1881, col. 4, "Wallack's New Theatre"; "Amusements: A New German Theatre" The New York Times September 16, 1881; "Mr. Boucicault" The New York Times March 27, 1883; "Events in the Metropolis: Manager Neundorff's Ill Luck" The New York Times June 28, 1883; "The Star Theatre" The New York Times August 19, 1883; and Elson:119

- ^ "The Star Theatre" The New York Times August 21, 1883; "Francesca da Rimini" The New York Times August 28, 1883; and "The Man in the Lobby" The New York Times December 13, 1883

- ^ Brown v2:303–20

- ^ Obituary: "John B. Schoeffel Dies in Boston at 72" The New York Times September 1, 1918

- ^ Untitled obituary: The New York Times March 15, 1907

- ^ "Seasick, But Funny" The New York Times April 24, 1888

- ^ "Theatrical Gossip" The New York Times July 18, 1888

- ^ "Running Wild" The New York Times January 22, 1889

- ^ "The Crystal Slipper" The New York Times November 27, 1888; and Franceschina

- ^ Plans: "The Star's Next Season" The New York Times January 8, 1889; accomplished: "Changes at the Star" The New York Times September 8, 1889; capacity: "Theatrical Gossip" The New York Times March 20, 1890, col. 2 (scroll down)

- ^ "Just Where to Get Cool" The New York Times August 2, 1890

- ^ Brown v2:327-38; "Theatres Follow Population" The New York Times April 18, 1895; "New Policy of the Star Theatre" The New York Times May 15, 1895; and "Neil Burgess Secures the Star" The New York Times May 23, 1895

- ^ "Neil Burgess's Star Theatre" The New York Times October 10, 1895; "Mr. Burgess in a New Play" The New York Times November 3, 1895; and "Amusements. The Star Theatre Opened by Neil Burgess in The Year One" The Sun (New York) November 3, 1895, p. 4 col. 6 (scroll down)

- ^ Brown v2:338–42

- ^ "The Star Theatre to Remain" and "Neil Burgess a Bankrupt" The New York Times March 10, 1899 (scroll down); "Neil Burgess Out of Bankruptcy" The New York Times April 27, 1899 (scroll down); and "The Star Theatre Leased" The New York Times August 9, 1899 (scroll down)

- ^ Brown v2:343

- ^ "The Star Now a Memory" The New York Times April 21, 1901. "Famous Star Theatre is to be Torn Down" The New York Times April 7, 1901 has an interview with a veteran of both the 485 and 844 companies.

- ^ See

- "Star Theatre / American Mutoscope and Biograph Company". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- Eagan, Daniel. (2010). America's film legacy:the authoritative guide to the landmark movies in the National Film Registry. National Film Preservation Board (U.S.). New York: Continuum. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781441116475. OCLC 676697377.

- ^ "New Building on Star Theatre's Site" The New York Times November 30, 1899 (scroll down)

- ^ Emporis Website, "One Union Square South"[usurped]. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ For 1885 map, see Robinson, Plate 13.

- ^ Wallack:24

- ^ "Wallack's New Theatre" The New York Times December 4, 1881. Details at "Wallack's Uptown House" The New York Times February 8, 1881. The White property was supplemented by two row-houses and later a third (29-33 West 30th Street), which were demolished to make room for the stage, except that half of each, facing the street, was carefully preserved for dressing rooms.

- ^ "Wallack's" The New York Times May 2, 1915

- ^ a b "Federal Building", Sarasota History Alive! website. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "Connecticut's Civil War Monuments" > Soldiers and Sailors' Monument, Connecticut Historical Society website. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ The American Architect and Building News Vol. 13, No. 367 (January 6, 1883). "The Illustrations", p. 6, with drawings on the following pages.

- ^ White, "The Lambs Club," location 8467. The building is now (2012) The Chatwal New York Hotel, with a restaurant called The Lambs Club.

- ^ King:551

- ^ King:550

- ^ a b See

- Alias Jimmy Valentine

- Alias Jimmy Valentine at Internet Broadway Database

- "Big Thrill in New Play by Armstrong" The New York Times January 22, 1910

- ^ Brown v3:310–11.

- Oscar Wilde lectured at the theater on May 11 ("Mr. Wilde on Decorative Art" The New York Times May 12, 1882).

- For an overview of this theater's history, see Burnham, especially from p. 74, last paragraph.

- ^ Jenkins:252

- ^ Brown v3:324–25 and "The Close of Mr. Wallack's Season". New-York Daily Tribune. May 29, 1887. p. 5, column 1.

- ^ a b Brown v3:324–25; "The Changes at Wallack's" The New York Times May 11, 1887; and "John Lester Wallack's Will". New-York Daily Tribune. January 9, 1889. p. 7, column 3.

- ^ a b Brown v3:325–29; "Amusements. Wallack's Theatre – The Stock Company's Farewell" The New York Times February 12, 1888; "Amusements. The Last Night at Wallack's" The New York Times May 6, 1888; and Montgomery, George Edgar (1889). "The Last Year of 'Wallack's'". In Fuller, Edward (ed.). The Dramatic Year 1887–1888. Boston: Ticknor and Company. p. 62.

- ^ a b Brown v3:329 and "Mr. Palmer Has Wallack's" The New York Times July 22, 1888

- ^ Brown v3:329; "Death of Lester Wallack" The New York Times September 7, 1888; and "Forty Years on the New-York Stage" The New York Times September 7, 1888

- ^ Brown v3:331–56

- ^ "Mr. Moss in Possession" The New York Times November 20, 1896

- ^ Brown v3:356–67

- ^ See

- Brown v3:367

- Theodore Moss obituary The New York Times July 14, 1901; "Topics of the Times" The New York Times 1901-07-19 (last item); "Theodore Moss's Will" The New York Times July 20, 1901 (scroll down)

- "Theodore Moss Dies" New-York Tribune July 14, 1901, p. 4 col. 4; "Theodore Moss to Lie in Woodlawn", New-York Tribune July 16, 1901, p. 9 col. 4

- "The Eve of the Long Fast" The New York Times March 2, 1881 (on eldest daughter's marriage)

- "Mrs. Arthur Wallack Dead" The New York Times July 9, 1888 (on eldest daughter's death)

- "Married at the Waldorf" The New York Times September 15, 1896 (scroll down; on second daughter's marriage)

- ^ "Future of Wallack's Theatre" New-York Tribune July 19, 1901:6, col. 6 (bottom)

- ^ "Notes of the Stage" The New York Times May 15, 1902 (fourth paragraph). Note the mention of Mrs. Lester Wallack's benefit the same month (first paragraph).

- ^ "New Plays Last Night. The Sultan of Sulu at Wallack's" The New York Times December 30, 1902

- ^ "George Ade in Comedy" The New York Times November 25, 1903

- ^ The Sho-Gun at Internet Broadway Database

- ^ "How the Squaw Man is not the Shawman" The New York Times October 24, 1905

- ^ "Sam Bernard's New Play" The New York Times October 23, 1906

- ^ "A Knight for a Day Pleases" The New York Times December 17, 1907

- ^ "An Exquisite Idyl of Georgian Days" The New York Times December 21, 1910

- ^ "Arliss as 'Disraeli' in a Parker Romance" The New York Times September 19, 1911

- ^ "Lots of Suspense in Maude's New Play" The New York Times November 25, 1913

- ^ Death notice, The New York Times January 16, 1910, col. 2

- ^ "Burnham Leases Wallack's" The New York Times April 6, 1910 (scroll down)

- ^ "Wallack's Theatre in Trade" Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide Vol. 95, No. 2443 (January 9, 1915):58, col. 3

- ^ "Barker's Season Happily Launched" The New York Times January 28, 1915

- ^ "End of Wallack's Theatre" Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide Vol. 95, No. 2451 (March 6, 1915):375, col. 1; "Wallack's Theatre to Go" The New York Times March 4, 1915 (scroll down); and "Mid-Broadway Changes" The New York Times March 7, 1915;

- ^ "Farewell at Wallack's Tonight" The New York Times May 1, 1915 (scroll down); and "Wallack's" The New York Times 1915-05-02; Patterson, Ada "The Stage Honors Rose Coghlan" Theatre Magazine Vol. 36, No. 256 (July 1922), p. 36, col. 1, last paragraph and following.

- ^ Emporis Website, "29 West 30th Street"[usurped] and "1220 Broadway"[usurped]. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- "The Theater's on a Roll, Gliding Down 42nd Street" The New York Times February 28, 1998

- Anco Cinema at Internet Broadway Database

Sources

- Brown, Thomas Allston A History of the New York Stage, Vol. 1. Dodd, Mead and Company; New York; 1903

- Brown, Thomas Allston A History of the New York Stage, Vol. 2. Dodd, Mead and Company; New York; 1903

- Brown, Thomas Allston A History of the New York Stage, Vol. 3. Dodd, Mead and Company; New York; 1903

- Browne, Junius Henri The Great Metropolis; A Mirror of New York. American Publishing Company, Hartford, 1869

- Burnham, Charles "The Passing of Wallack's" [the link on the Contents page goes to the wrong volume], in The Theatre, Vol. 21 No. 168 (February 1915):72

- Elson, Louis Charles and Elson, Arthur The History of American Music, revised ed. Macmillan, New York and London, 1915

- Florence, W. J. "Lester Wallack" in The North American Review, Vol. 147 No. 383 (1888-10), pp. 453–59. Online at JSTOR.

- Franceschina, John Harry B. Smith. Routledge, New York, 2003; pp. 36–40

- Fulton History website. Searchable archive of old New York State newspapers; no permanent links.

- Ireland, Joseph N. Records of the New York Stage, Vol. 2. T. H. Morrell, New York, 1867

- Jenkins, Stephen The Greatest Street in the World. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1911

- King, Moses King's Handbook of New York City. Moses King, Boston, 1892; pp. 538 (Brougham's), 550–51 (Palmer's), 557–58 (Star)

- McCarthy, Justin Huntly, M.P. Ireland since the Union. Chatto & Windus, Piccadilly, London, 1887

- Perris, William Maps of the City of New York, Vol. 3. Perris & Browne, 1853

- Perris, William Maps of the City of New York, [Third Edition,] Vol. 4. Perris & Browne, New York, 1859

- Phelps, H. P. Players of a Century: A Record of the Albany Stage, 2nd edition. Edgar S. Werner, New York, 1890 [1st edition. Joseph McDonough, Albany, 1880]

- Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide F. W. Dodge Corp., New York. Online at Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections.

- Robinson, E. & Pidgeon, R. H. Robinson's Atlas of the City of New York. (New York: E. Robinson, 1885)

- Wallack, Lester and Hutton, Laurence Memories of Fifty Years. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1889

- White, Norval and Willensky, Elliot AIA Guide to New York City, 5th ed., Kindle version. Oxford University Press, New York, 2010

- Winter, William Brief Chronicles, Part I. Publications of the Dunlap Society, No. 7, New York, 1889

External links

[edit]- Internet Broadway Database website:

- "Broadway Theatre" (485 Broadway)

- "Star Theatre" (844 Broadway)

- "Wallack's Theatre" (30th Street and Broadway)

40°43′18″N 74°00′01″W / 40.72169°N 74.00020°W 40°44′03″N 73°59′27″W / 40.73404°N 73.99070°W 40°44′49″N 73°59′17″W / 40.74690°N 73.98809°W

- Former Broadway theatres

- Demolished theatres in New York City

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manhattan

- John M. Trimble buildings

- 1850 establishments in New York (state)

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 1901

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 1869

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 1915

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 1931