Warcraft: Orcs & Humans

| Warcraft: Orcs & Humans | |

|---|---|

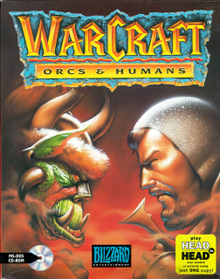

Box art for Warcraft: Orcs & Humans | |

| Developer(s) | Blizzard Entertainment |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Patrick Wyatt[3] |

| Producer(s) | Bill Roper Patrick Wyatt |

| Programmer(s) | Bob Fitch Jesse McReynolds Michael Morhaime Patrick Wyatt |

| Composer(s) | Gregory Alper |

| Series | Warcraft |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Classic Mac OS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Real-time strategy[4] |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer[4] |

Warcraft: Orcs & Humans is a real-time strategy game (RTS) developed and published by Blizzard Entertainment, and published by Interplay Productions in Europe. It was released for MS-DOS in North America on 15 November 1994, and for Mac OS in early 1996. The MS-DOS version was re-released by Sold-Out Software in 2002.

Although Warcraft: Orcs & Humans is not the first RTS game to have offered multiplayer gameplay, it persuaded a wider audience that multiplayer capabilities were essential for future RTS games. The game introduced innovations in its mission design and gameplay elements, which were adopted by other RTS developers.

Warcraft games emphasize skillful management of relatively small forces, and they maintain characters and storylines within a cohesive fictional universe. Sales were fairly high, reviewers were mostly impressed, and the game won three awards and was a finalist for three others. The game's sequel, Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, became the main rival to the Command & Conquer series by Westwood Studios. This competition fostered an "RTS boom" in the mid– to late 1990s.

Gameplay

[edit]Warcraft: Orcs & Humans is a real-time strategy game (RTS).[4][5][6] The player takes the role of either the Human inhabitants of Azeroth, or the invading Orcs.[7][8] In the single player campaign mode the player works through a series of missions, the objective of which varies, but usually involves building a small town, harvesting resources, building an army and then leading it to victory.[4] In multiplayer games, the objective is always to destroy the enemy players' forces. Some scenarios are complicated by the presence of wild monsters, but sometimes these monsters can be used as troops.[9][10][11] The game plays in a medieval setting with fantasy elements. Both sides have melee units and ranged units, as well as spellcasters.[5]

Modes

[edit]Gameplay of Warcraft: Orcs & Humans expands the Dune II "build base, build army, destroy enemy" paradigm to include other modes of game play.[4] These include several new mission types, such as conquering rebels of the player's race, rescuing and rebuilding besieged towns, rescuing friendly forces from an enemy camp and then destroying the main enemy base, and limited-forces missions, in which neither side can make further units, and making efficient use of one's platoon is a key strategy element.[12] In one mission, the player has to kill the Orc chief's daughter.[13]

The game allows two players to compete in multiplayer contests by dialup modem or local networks,[14] and enables gamers with the MS-DOS and Macintosh version to play each other.[13] Multiplayer and AI skirmishes that are not part of campaigns were supported by a random map generator.[4][13][14] The game also allowed spawn installations to be made.[13]

Economy and power

[edit]Warcraft requires players to collect resources, and to produce buildings and units in order to defeat an opponent in combat.[4] Non-combatant builders deliver the resources to the Town Center from mines, from which gold is dug, and forests, where wood is chopped.[5] As both are limited resources which become exhausted during the game, players must collect them efficiently, and also retain forests as defensive walls in the early game when combat forces are small.[12]

The lower-level buildings for Humans and Orcs have the same functions, but different sprites.[4] The Town Hall stores resources and produces units that collect resources and construct buildings. Each Farm provides food for up to four units, and additional units cannot be produced until enough Farms are built.[15][16] The Barracks produces all non-magical combat units, including melee, ranged, mounted, and siege units. However all except the most basic also need assistance from other buildings,[15] some of which can also upgrade units.[13]

Each side can construct two types of magical buildings, each of which produces one type of spellcaster and researches more advanced spells for that type.[7] These advanced buildings can be constructed only with assistance from other buildings.[15][16][17][18] The Human Cleric and Orc Necrolyte can both defend themselves by magic and also see distant parts of the territory for short periods.[19][20] The Cleric's other spells are protective, healing the injured and making troops invisible,[19] while the Necrolyte raises skeletons as troops and can make other units temporarily invulnerable, at the cost of severely damaging them when the spell dissipates.[20] The Human Conjurer and Orc Warlock have energy blasts, wider-range destruction spells and the ability to summon small, venomous monsters. The Conjurer can summon a water elemental, while the Warlock can summon a demonic melee unit.[19][20]

User interface

[edit]

The main screen has three areas: the largest, to the right, is the part of the territory on which the player is currently operating; the top left is the minimap; and, if a building or unit(s) is selected, the bottom left shows their status and any upgrades and the actions that can be performed.[21] The status details include a building's or unit's health, including its progress if being constructed, and any upgrades the object has completed.[12] The Menu control, at the very bottom on the left, provides access to save game, load game and other menu functions.[21]

Initially most of the main map and minimap are blacked out, but the visible area expands as the player's units explore the map. The mini-map shows a summary of the whole territory, with green dots for the player's buildings and units and red dots for enemy ones. The player can click in the main map or the minimap to scroll the main map around the territory.[21]

All functions can be invoked by the mouse. Keys can also invoke the game setup, some of the menu options and some gameplay functions including scrolling and pausing the game.[21] Players can select single units by clicking, and groups of up to four by shift-clicking or bandboxing.[13][21] To move units, players can shift the mouse to select units on the main map, move to the unit menu to select an action, and then back to the main map or minimap to specify the target area; shortcut keys can eliminate the middle mouse action in this cycle.[12][21]

Storyline

[edit]Backstory

[edit]The Orcs originate from another world. A warlike species, they conquered everyone else around them, and eventually, the various Orc clans started scheming against one another. The Warlock clan, noticing these developments, tried to find a solution and prevent the Orcs from turning on one another. The Warlocks noticed a rift between the dimensions and, after many years, opened a small portal to another world. One Warlock explored and found a region, called Azeroth by its Human inhabitants, from which the Warlock returned with strange plants as evidence of his discovery.[22]

The Orcs enlarged the portal until they could transport seven warriors, who massacred a Human village. The raiding party brought back samples of good food and fine worksmanship, and a report that the Humans were defenseless. The Orcs' raiding parties grew larger and bolder, until they assaulted Azeroth's principal castle. However, the Humans had been training warriors of their own, especially the mounted, heavily armed Knights. These, assisted by Human Sorcerers, gradually forced the Orcs to retreat through the portal, which the Humans had not discovered.[22]

For the next fifteen years, one faction of Orcs demanded that the portal be closed. However a chief of exceptional cunning realized that the Humans, although out-numbered, had prevailed through the use of superior tactics, organization, and by magic. He united the clans, imposed discipline on their army and sought new spells from the Warlocks and Necromancers. Their combined forces were ready to overthrow the Humans.[22]

Characters

[edit]Several important characters are introduced in WarCraft: Orcs and Humans. The two campaigns center around unnamed player characters in positions of high importance. WarCraft II: Tides of Darkness reveals the player character of the orc campaign to be Orgrim Doomhammer, who begins the game as a lieutenant of the ruling Warchief, Blackhand the Destroyer. The human player character begins as a regent over a small section of Azeroth, appointed by King Llane Wrynn. Other characters present in the game include Garona, a half-orc spy who is ostensibly a diplomat to the humans, Medivh, the most powerful magician of Azeroth, and Anduin Lothar, one of the greatest champions of Azeroth.

Game

[edit]The game's two campaigns are exclusive to each other.

After several battles against the Human forces, the Orcish campaign culminates with the Orc commander killing Blackhand and overthrowing him, sacking Stormwind, killing King Llane and becoming victorious as the new Warchief.[23]

The Human campaign involves the rescue of the trapped Anduin Lothar, and the killing of Medivh, who has become insane. King Llane is killed by Garona, but before his death, wishes that the player character becomes the commander of the Human forces. The player character marches on Blackrock Spire and destroys the Horde. After the Human victory, the player character becomes the new King of Stormwind.[24]

In WarCraft II: Tides of Darkness, it was revealed that the canonical campaign was the Orcish one, though many events from the Human campaign were confirmed to be canonical in later games, such as the assassination of Llane by Garona and the death of Medivh.

Development and publication

[edit]Though the earliest real-time strategy games appeared in the 1980s,[25][26] notably the multiplayer RTS game Herzog Zwei,[27] and others followed in the early 1990s,[28] the pattern of modern RTS games was established by Dune II, released by Westwood Studios for DOS in 1992.[6][28] Inspired by Dune II and Herzog Zwei,[29] Blizzard Entertainment was surprised that no additional RTS games appeared in 1993 and early 1994[4][7] – although in fact Westwood had quietly been working on Command & Conquer since the completion of Dune II.[30] To take advantage of the lull in RTS releases, Blizzard produced Warcraft: Orcs & Humans. According to Patrick Wyatt, the Producer on Warcraft, Warhammer was a huge inspiration for the art-style of Warcraft. [31] According to Bob Fitch, the theme for Warcraft was inspired by the vikings of The Lost Vikings, combined with masses of creatures under their automated control similar to Lemmings, and adding the multiplayer element of having these opposing masses of vikings meet up and fight each other.[32]

Though subsequent "craft" games are famous for having complex stories presented lavishly,[33] the first installment of the series had no script and the plot was improvised in the recording studio by producer and sole voice-actor Bill Roper.[34] The contract composer Gregory Alper wrote music that Blizzard staff found reminiscent of Holst's The Planets.[35] Demos in mid-1994 whetted appetites for the completed game, released for MS-DOS in November 1994[4][7] and for the Macintosh in 1996.[13] The game was published by Blizzard in North America and by Interplay Entertainment in Europe,[2] and Sold-Out Software republished the MS-DOS version in March 2002.

Warcraft: Orcs & Humans was originally intended to be the first in a series of Warcraft-branded war games in fictional and real settings (such as a proposed Warcraft: Vietnam). Blizzard executives considered that customers would think that a brand with many similar games on shelves was serious and well-supported. The name "Warcraft" was proposed by Blizzard developer Sam Didier, and was chosen because "it sounded super cool", according to Blizzard co-founder Allen Adham, without any particular meaning attached to it.[36]

Reception

[edit]| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer Gaming World | |

| Dragon | |

| GameRevolution | A−[39] |

| Next Generation | |

| Mac Gamer | 92% (MAC)[13] |

| Abandonia | 4.0[41] |

| Just Games Retro | 78%[12] |

| Secret Service | 90%[42] |

Warcraft: Orcs & Humans became a success, and for the first time made the company's finances secure.[7] Within one year of release, its sales surpassed 100,000 units.[43] It ultimately sold 300,000 copies.[44] In November 1995 Entertainment Weekly reported that the game ranked 19th out of the top 20 CDs across all categories.[45]

The game was released in November 1994.[46] Although reviews did not appear until months later,[7] in Dragon Paul Murphy described the game as "great fun – absorbing and colorful",[47] and Scott Love praised its solid strategy, simple interface, and fantasy theme.[13] Warcraft: Orcs & Humans won PC Gamer's Editors' Choice Award, Computer Life's Critics' Pick, and the Innovations Award at the Consumer Electronics Show, Winter 1995. It was a finalist for Computer Gaming World's Premier award, PC Gamer's Strategy Game of the Year, and the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences's Best Strategy award.[48] In 1996, Computer Gaming World declared Warcraft the 125th-best computer game ever released.[49]

S. Love of MacWEEK found the play to be hard work, as two or three of the player's units would often attack without orders, while the rest still did nothing, and buildings could also lie idle without orders.[50]

In a retrospective review, the J-Man of Just Games Retro said the game is overly slow, as the player must produce a few basic buildings and peasants in order to gather resources, and then start building combat units, while the enemy starts with more buildings and the ability to immediately send out offensive units to undo the player's efforts. He also criticized that the basic units of the two sides are essentially identical and that the interface is clunky, but praised the resource system and effective enemy AI.[12]

GameSpot's retrospective on real-time strategy history said the game's AI was unintelligent and predictable,[4] and Scott Love said a difficulty setting would have increased the game's longevity.[13] Reviewers found the pathfinding poor.[4][51] Both Scott Love and the J-Man said the game runs very slowly during large battles.[12][13]

Some reviewers said the stereo sound helped gamers to locate events that occurred outside the current viewport.[13][39] K. Bailey of 1UP liked units' speech effects, especially those in response to repeated clicks,[51] while Scott Love and the J-Man found this aspect monotonous.[12][13] Game Revolution's review of the Mac version complained that its graphics, which were ported from the DOS version's VGA, did not exploit the Macintosh's superior resolution.[39] However, Game Revolution and Mac Gamer agreed that visual shortcomings did not reduce Mac gamers' enjoyment of the engrossing gameplay. Both also complained that the Macintosh was released about a year later than the DOS version.[13][39] In contrast, a reviewer for Next Generation, while not overlooking the fact that Warcraft II was already out by the time the Macintosh version was released, made no criticism on this point, and asserted that "amazingly easy to pick up and play, Warcraft still manages to offer enough challenge to keep gaming veterans happy for hour after hour. Completed by sharp graphics, and good voice acting, the only thing holding this game back at all is its somewhat limited play options ..."[40]

Legacy

[edit]While RTS games date back to the 1980s,[26][52] Dune II, released in 1992, established conventions that most subsequent RTS games followed,[53] including the "collect resources, build base and army, destroy opponents" pattern.[5] Warcraft: Orcs & Humans, two years later, is the subsequent well-known RTS game,[4] and introduced new types of missions, including conquering rebels of the player's race and limited-forces missions, in which neither side could make additional units.[4][12][13] It also includes skirmishes which are single-player games that are not part of a larger campaign. To support multiplayer and skirmishes, Warcraft: Orcs & Humans uses a random map generator,[4] a feature previously seen in the turn-based strategy game Civilization.[54][55] In 1995 Westwood's RTS Command & Conquer series adopted the use of nonstandard mission types and skirmishes,[56][57] and Microsoft's Age of Empires (1997) includes these features and a random map generator.[58]

While not the first modem multiplayer RTS game,[26] Warcraft: Orcs & Humans allows two gamers to compete by modem or local networks,[14] which persuaded a wider audience that multiplayer competition was much more challenging than contests against the artificial intelligence (AI), and made multiplayer facilities essential for future RTS games.[7]

Realms, released in 1991 for DOS, Amiga, and Atari ST, has a medieval theme,[59] with melee and ranged units, and allows gamers to resolve combat automatically or in a RTS-type style.[60][61] Warcraft: Orcs & Humans is the first typical RTS to be presented in a medieval setting, and its units included spellcasters as well as melee and ranged units.[4]

Sequels

[edit]The success of Warcraft: Orcs & Humans prompted a sequel, Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, in December 1995,[4][51] and an expansion pack, Warcraft II: Beyond the Dark Portal, in 1996.[7] In late 1995 Westwood had released Command & Conquer, and the competition between these two games popularized and defined the RTS genre.[51][62] Blizzard's new game includes these enhancements: naval and air units, supported by new buildings, and the new resource of oil;[63] higher-resolution artwork rendered in SVGA graphics; improved sound, including additional responses from units; a much better AI; and new mechanisms such as patrolling (moving continuously along a route for surveillance or defense).[64] A further generation of the Warcraft: Orcs & Humans lineage, called Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos, was released in July 2002,[65] and gained instant and enduring acclaim with both critics and players.[66]

In April 1998, Blizzard released StarCraft, an RTS with the concepts and mechanisms of Warcraft but an interplanetary setting and three totally different races.[67] StarCraft and its expansion StarCraft: Brood War were well received by critics and became very successful.[68] World of Warcraft, released in North America in November 2004[69] and in Europe in February 2005, is Blizzard's first massively multiplayer online role-playing game. It uses the universe of the Warcraft RTS games, including characters that first appeared in Warcraft: Orcs & Humans.[70] WoW received high praise from critics, is the most popular MMORPG of 2008,[71] and in 2007 became the most profitable video game ever created.[72]

Beyond video games, the extended Warcraft franchise includes board games,[73] card games,[74] books,[75] and comics.[76]

Blizzard's style of RTS games

[edit]Warcraft: Orcs & Humans was a moderate critical and commercial success,[45] and laid the ground for Blizzard's style of RTS, in which personality was a distinctive element. The increasingly humorous responses to clicking a unit repeatedly became a trademark of the company. The game introduced characters that also appeared in the enormously successful massively multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft. The company's manuals present detailed backstories and artwork.[51] StarCraft has a futuristic theme, but places the same emphasis on characterization. In all the Blizzard RTS games and in World of Warcraft, units must be managed carefully, rather than treated as expendable hordes. Blizzard has produced fewer expansion packs than Westwood, but integrated the story of each with its predecessors.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ "Blizzard's 'Warcraft: Orcs and Humans' Now Available - Press Release". Blizzard Entertainment. 15 November 1994.

- ^ a b Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac) copyright page

- ^ Wyatt, Patrick (25 July 2012). "The making of Warcraft part 1". Code of Honor. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Geryk, B. "GameSpot Presents: A History of Real-Time Strategy Games – The First Wave". Archived from the original on 20 November 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d Geryk, B. "GameSpot Presents: A History of Real-Time Strategy Games – Introduction". Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ a b Cobbett, R. (27 September 2006). "The past, present and future of RTS gaming – TechRadar UK". Future Publishing Limited. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fahs, T. (18 August 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Warcraft – Dawn of Azeroth". IGN. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 17–20

- ^ "Warcraft: Orcs and Humans – PC Review – Coming Soon Magazine!". Coming Soon Magazine!. 1994. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 31–34

- ^ Warcraft 1 Manual: Orcs (Mac), pp. 31–34

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Just Games Retro – Warcraft: Orcs and Humans". Just Games Retro. 26 May 2008. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Wrobel, J. (May 1996). "Warcraft: Orcs and Humans (Mac Gamer)". Archived from the original on 9 May 2003. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ a b c Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), p. 3

- ^ a b c Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 27–30

- ^ a b Warcraft 1 Manual: Orcs (Mac), pp. 27–29

- ^ Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 21–23

- ^ Warcraft 1 Manual: Orcs (Mac), pp. 21–23

- ^ a b c Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 24–26

- ^ a b c Warcraft 1 Manual: Orcs (Mac), pp. 24–26

- ^ a b c d e f Warcraft 1 Manual: Humans (Mac), pp. 5–15

- ^ a b c Warcraft 1 Manual: Orcs (Mac), pp. 17–20

- ^ Blizzard Entertainment. WarCraft: Orcs and Humans (PC). Level/area: Human, mission 12: "Stormwind Keep".

- ^ Blizzard Entertainment. WarCraft: Orcs and Humans (PC). Level/area: Human, mission 12: "Black Rock Spire".

- ^ Adams, D. (7 April 2006). "The State of the RTS". IGN. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ a b c Baker, T. Byrl, Unsung Heroes: Ground Breaking Games – Modem Wars, GameSpot, archived from the original on 7 July 2010, retrieved 30 October 2014

- ^ DGC Ep 24: Interview with Bill Roper, Dev Game Club (18 August 2016)

- ^ a b Walker, M.H. (2004). "Strategy Gaming: Part I – A Primer". GameSpy Industries. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "Warcraft Anniversary Interview". IGN. 23 November 2009.

- ^ Geryk, B. "GameSpot Presents: A History of Real-Time Strategy Games – Command & Conquer". Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ "How Warcraft Was Almost a Warhammer Game (and how That Saved WoW)". 26 July 2012.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (15 August 2017). "WarCraft Was Originally Conceived in Part as "Lost Vikings Meets RTS"... And Lemmings". US Gamer. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ a b Hoeger, J. "Retronauts Presents: Blizzard vs. Westwood". The 1UP Network. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Fahs, T. (18 August 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Warcraft – The Lost Chapter". IGN. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Kelly, R.K. "Masters of the Craft: Blizzard's Composers". GameSpy Industries. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ^ Menegus, Bryan (1 October 2019). "How Warcraft Got Its Name". Kotaku. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Lombardi, Chris (January 1995). "War Crime in Real Time". Computer Gaming World. No. 126. pp. 228–232.

- ^ Jay & Dee (July 1995). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon. No. 219. pp. 57–60, 65–66.

- ^ a b c d "Warcraft review for the MAC". Game Revolution. 1996. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Warcraft". Next Generation. No. 15. Imagine Media. March 1996. p. 96.

- ^ "Warcraft – Orcs and Humans – Abandonia". Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Berger (February 1995). "Warcraft". Secret Service Magazine (in Polish). Vol. 22. pp. 64–65.

- ^ "Blizzard Entertainment - 10th Anniversary Feature". Archived from the original on 11 February 2001. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Goldberg, Harold (5 April 2011). All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture. Crown Archetype. p. 172. ISBN 978-0307463555.

- ^ a b "Battle Access". Entertainment Weekly. No. 299. 3 November 1995. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009. 5 of the 20 titles are non-gamer products by Microsoft.

- ^ Magrino, T. (26 November 2009). "Spot On: 15 years of Warcraft". CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Rolston, Ken; Murphy, Paul; Cook, David (August 1995). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon. No. 220. pp. 63–68.

- ^ "Blizzard Entertainment: Awards". Blizzard Entertainment. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Staff (November 1996). "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. No. 148. pp. 63–65, 68, 72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 94, 98.

- ^ Love, S. (4 December 1995). "Warcraft: Orcs and Humans". MacWEEK. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Bailey, K. (16 November 2009). "WarCraft and the Birth of Real-time Strategy". The 1UP Network. Retrieved 18 November 2009.Bailey, K. (2008). "Top 5 Overlooked Prequels". Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Adams, D. (7 April 2006). "The State of the RTS". IGN. pp. 1–7. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ All the action appears on a single screen; players developed bases, in which buildings were constructed in a defined sequence; and bases produced combat units. Kosak, D. (4 February 2004). "Top Ten Real-Time Strategy Games of All Time – Dune II". GameSpy. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ "Pre-Game Options". Sid Meier's Civilization – Build An Empire To Stand The Test Of Time. MicroProse Software. 1991. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Edwards, B. (18 July 2007). "The History of Civilization". Gamasutra. Think Services. Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Murff, T. (1997). "Conquer The World with the Click of a Mouse". InfoMedia, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ Broady, V. (26 November 1996). "Command & Conquer Red Alert Review for PC – GameSpot". CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ "Playing the game". Age of Empires manual. Microsoft. 1997. pp. 4–5.

- ^ "Strategists will enjoy 'Warcraft'" (PDF). Toledo Blade. Toledo, OH. Knight-Ridder News Service. 2 March 1995. p. 37. Retrieved 22 November 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sly, P. "Amiga – Realms". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Realms". Classic PC Games. February 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Buchanan, L. (22 October 2008). "Top 10 PC Games That Should Go Console". IGN. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ Warcraft II (Battle.net ed.). Reading, Berkshire, United Kingdom: Blizzard Entertainment. 1995–1999. pp. 31, 42–47, 51–55, 72–74, 78–81.

- ^ Geryk, B. "GameSpot Presents: A History of Real-Time Strategy Games – The Sequels". Archived from the original on 26 November 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Ciabai, C. (11 April 2008). "WarCraft III Cheats (PC)". Softpedia. SoftNews NET SRL. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Fahs, T. (18 August 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Warcraft – War Heroes". IGN. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Olafson, P. (24 November 2000). "Starcraft Review from GamePro". GamePro Media. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "Starcraft (pc) reviews at Metacritic.com". CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "Blizzard Entertainment Announces World of Warcraft Street Date – November 23, 2004". Blizzard Entertainment. 4 November 2004. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Fahs, T. (18 August 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Warcraft – Taking on the World". IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2009). Craig Glenday (ed.). Guinness World Records 2009 (paperback ed.). Random House, Inc. p. 241. ISBN 9780553592566. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

Most popular MMORPG game(sic) In terms of the number of online subscribers, World of Warcraft is the most popular Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG), with 10 million subscribers as of January 2008.

- ^ Levine, R. (5 March 2007). "Spoils of Warcraft". CNNMoney.com. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "BoardGameGeek – Gaming Unplugged Since 2000". BoardGameGeek, LLC. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "World of Warcraft : 2009 World of Warcraft-card license meet global challenges in Texas". RPGRank.com. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Books : Warcraft : Warcraft Books". Simon & Schuster. Archived from the original on 6 December 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "WoW -> Community -> Comics". Blizzard Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on 10 August 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]The manual is organized as two separate books with separate page ranges, but in one binding. Both parts contain common sections such as the technical requirements and game set-up instructions.

- Warcraft: Orcs & Humans (Humans). Irvine, California: Blizzard Entertainment. 1994. (Mac version)

- Warcraft: Orcs & Humans (Orcs). Irvine, California: Blizzard Entertainment. 1994. (Mac version)