William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst | |

|---|---|

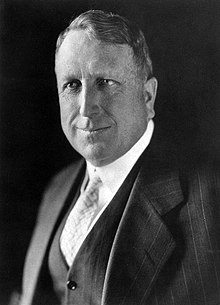

Hearst, c. 1910 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 11th district | |

| In office March 4, 1903 – March 3, 1907 | |

| Preceded by | William Sulzer (redistricting) |

| Succeeded by | Charles V. Fornes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 29, 1863 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 14, 1951 (aged 88) Beverly Hills, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Cypress Lawn Memorial Park |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Domestic partner | Marion Davies (1917–1951) |

| Children | at least 5, including George, William, John, Randolph Alleged: Patricia Lake |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Harvard University |

| Signature | |

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (/hɜːrst/;[1] April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboyant methods of yellow journalism in violation of ethics and standards influenced the nation's popular media by emphasizing sensationalism and human-interest stories. Hearst entered the publishing business in 1887 with Mitchell Trubitt after being given control of The San Francisco Examiner by his wealthy father, Senator George Hearst.[2]

After moving to New York City, Hearst acquired the New York Journal and fought a bitter circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer's New York World. Hearst sold papers by printing giant headlines over lurid stories featuring crime, corruption, sex, and innuendos. Hearst acquired more newspapers and created a chain that numbered nearly 30 papers in major American cities at its peak. He later expanded to magazines, creating the largest newspaper and magazine business in the world. Hearst controlled the editorial positions and coverage of political news in all his papers and magazines, and thereby often published his personal views. He sensationalized Spanish atrocities in Cuba while calling for war in 1898 against Spain. Historians, however, reject his subsequent claims to have started the war with Spain as overly extravagant.

He was twice elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives. He ran unsuccessfully for President of the United States in 1904, Mayor of New York City in 1905 and 1909, and for Governor of New York in 1906. During his political career, he espoused views generally associated with the left wing of the Progressive Movement, claiming to speak on behalf of the working class.

After 1918 and the end of World War I, Hearst gradually began adopting more conservative views and started promoting an isolationist foreign policy to avoid any more entanglement in what he regarded as corrupt European affairs. He was at once a militant nationalist, a staunch anti-communist after the Russian Revolution, and deeply suspicious of the League of Nations and of the British, French, Japanese, and Russians.[3] Following Hitler's rise to power, Hearst became a supporter of the Nazi Party, ordering his journalists to publish favorable coverage of Nazi Germany, and allowing leading Nazis to publish articles in his newspapers.[4] He was a leading supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932–1934, but then broke with FDR and became his most prominent enemy on the right. Hearst's publication reached a peak circulation of 20 million readers a day in the mid-1930s. He poorly managed finances and was so deeply in debt during the Great Depression that most of his assets had to be liquidated in the late 1930s. Hearst managed to keep his newspapers and magazines.

His life story was the main inspiration for Charles Foster Kane, the lead character in Orson Welles' film Citizen Kane (1941).[5] His Hearst Castle, constructed on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean near San Simeon, has been preserved as a State Historical Monument and is designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Early life and education

[edit]Hearst was born in San Francisco to George Hearst on April 29, 1863, a millionaire mining engineer, owner of gold and other mines through his corporation, and his much younger wife Phoebe Apperson Hearst, from a small town in Missouri. The elder Hearst later entered politics. He served as a U.S. Senator, first appointed for a brief period in 1886 and was then elected later that year. He served from 1887 to his death in 1891.

His paternal great-grandfather was John Hearst of Ulster Protestant origin. John Hearst, with his wife and six children, migrated to America from Ballybay, County Monaghan, Ireland, as part of the Cahans Exodus in 1766. The family settled in the Province of South Carolina. Their immigration there was spurred in part by the colonial government's policy that encouraged the immigration of Irish Protestants, many of Scots origin.[6] The names "John Hearse" and "John Hearse Jr." appear on the council records of October 26, 1766, being credited with meriting 400 and 100 acres (1.62 and 0.40 km2) of land on the Long Canes in what became Abbeville District, based upon 100 acres (0.40 km2) to heads of household and 50 acres (0.20 km2) for each dependent of a Protestant immigrant; the "Hearse" spelling of the family name was never used afterward by the family members themselves, nor any family of any size. Hearst's mother, née Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson, was also of Scots-Irish ancestry; her family came from Galway.[7] She was appointed as the first woman Regent of University of California, Berkeley, donated funds to establish libraries at several universities, funded many anthropological expeditions, and founded the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology.

Hearst attended preparatory school at St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire. He gained admission to Harvard College, and began attending in 1885. While there, he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon, the A.D. Club, a Harvard Final club, the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, and the Harvard Lampoon prior to being expelled. His antics at Harvard ranged from sponsoring massive beer parties on Harvard Square to sending pudding pots used as chamber pots to his professors with their images depicted within the bowls.[8]

Publishing business

[edit]

Searching for an occupation, in 1887 Hearst took over management of his father's newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, which his father had acquired in 1880 as repayment for a gambling debt.[9] Giving his paper the motto "Monarch of the Dailies", Hearst acquired the most advanced equipment and the most prominent writers of the time, including Ambrose Bierce, Mark Twain, Jack London, and political cartoonist Homer Davenport. A self-proclaimed populist, Hearst reported accounts of municipal and financial corruption, often attacking companies in which his own family held an interest. Within a few years, his paper dominated the San Francisco market.

New York Morning Journal

[edit]Early in his career at the San Francisco Examiner, Hearst envisioned running a large newspaper chain and "always knew that his dream of a nation-spanning, multi-paper news operation was impossible without a triumph in New York".[10] In 1895, with the financial support of his widowed mother (his father had died in 1891), Hearst bought the then failing New York Morning Journal, hiring writers such as Stephen Crane and Julian Hawthorne and entering into a head-to-head circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer, owner and publisher of the New York World. Hearst "stole" cartoonist Richard F. Outcault along with all of Pulitzer's Sunday staff.[11] Another prominent hire was James J. Montague, who came from the Portland Oregonian and started his well-known "More Truth Than Poetry" column at the Hearst-owned New York Evening Journal.[12]

When Hearst purchased the "penny paper", so called because its copies sold for a penny apiece, the Journal was competing with New York's 16 other major dailies. It had a strong focus on Democratic Party politics.[13] Hearst imported his best managers from the San Francisco Examiner and "quickly established himself as the most attractive employer" among New York newspapers. He was seen as generous, paid more than his competitors, and gave credit to his writers with page-one bylines. Further, he was unfailingly polite, unassuming, "impeccably calm", and indulgent of "prima donnas, eccentrics, bohemians, drunks, or reprobates so long as they had useful talents" according to historian Kenneth Whyte.[14]

Hearst's activist approach to journalism can be summarized by the motto, "While others Talk, the Journal Acts."

Yellow journalism and rivalry with the New York World

[edit]

The New York Journal and its chief rival, the New York World, mastered a style of popular journalism that came to be derided as "yellow journalism", so named after Outcault's Yellow Kid comic. Pulitzer's World had pushed the boundaries of mass appeal for newspapers through bold headlines, aggressive news gathering, generous use of cartoons and illustrations, populist politics, progressive crusades, an exuberant public spirit and dramatic crime and human-interest stories. Hearst's Journal used the same recipe for success, forcing Pulitzer to drop the price of the World from two cents to a penny. Soon the two papers were locked in a fierce, often spiteful competition for readers in which both papers spent large sums of money and saw huge gains in circulation.

Within a few months of purchasing the Journal, Hearst hired away Pulitzer's three top editors: Sunday editor Morrill Goddard, who greatly expanded the scope and appeal of the American Sunday newspaper; Solomon Carvalho; and a young Arthur Brisbane, who became managing editor of the Hearst newspaper empire and a well-known columnist. Contrary to popular assumption, they were not lured away by higher pay—rather, each man had grown tired of the office environment that Pulitzer encouraged.[15]

While Hearst's many critics attribute the Journal's incredible success to cheap sensationalism, Kenneth Whyte noted in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise Of William Randolph Hearst: "Rather than racing to the bottom, he [Hearst] drove the Journal and the penny press upmarket. The Journal was a demanding, sophisticated paper by contemporary standards."[16] Though yellow journalism would be much maligned, Whyte said, "All good yellow journalists ... sought the human in every story and edited without fear of emotion or drama. They wore their feelings on their pages, believing it was an honest and wholesome way to communicate with readers", but, as Whyte pointed out: "This appeal to feelings is not an end in itself... [they believed] our emotions tend to ignite our intellects: a story catering to a reader's feelings is more likely than a dry treatise to stimulate thought."[17]

The two papers finally declared a truce in late 1898, after both lost vast amounts of money covering the Spanish–American War. Hearst probably lost several million dollars in his first three years as publisher of the Journal (figures are impossible to verify), but the paper began turning a profit after it ended its fight with the World.[18]

Under Hearst, the Journal remained loyal to the populist or left wing of the Democratic Party. It was the only major publication in the East to support William Jennings Bryan in 1896. Its coverage of that election was probably the most important of any newspaper in the country, attacking relentlessly the unprecedented role of money in the Republican campaign and the dominating role played by William McKinley's political and financial manager, Mark Hanna, the first national party 'boss' in American history.[19] A year after taking over the paper, Hearst could boast that sales of the Journal's post-election issue (including the evening and German-language editions) topped 1.5 million, a record "unparalleled in the history of the world."[20]

The Journal's political coverage, however, was not entirely one-sided. Kenneth Whyte says that most editors of the time "believed their papers should speak with one voice on political matters"; by contrast, in New York, Hearst "helped to usher in the multi-perspective approach we identify with the modern op-ed page".[21] At first he supported the Russian Revolution of 1917 but later he turned against it. Hearst fought hard against Wilsonian internationalism, the League of Nations, and the World Court, thereby appealing to an isolationist audience.[22]

Spanish–American War

[edit]

The Morning Journal's daily circulation routinely climbed above the 1 million mark after the sinking of the Maine and U.S. entry into the Spanish–American War, a war that some called The Journal's War, due to the paper's immense influence in provoking American outrage against Spain.[23] Much of the coverage leading up to the war, beginning with the outbreak of the Cuban Revolution in 1895, was tainted by rumor, propaganda, and sensationalism, with the "yellow" papers regarded as the worst offenders. The Journal and other New York newspapers were so one-sided and full of errors in their reporting that coverage of the Cuban crisis and the ensuing Spanish–American War is often cited as one of the most significant milestones in the rise of yellow journalism's hold over the mainstream media.[24] Huge headlines in the Journal assigned blame for the Maine's destruction on sabotage, which was based on no evidence. This reporting stoked outrage and indignation against Spain among the paper's readers in New York.

The Journal's crusade against Spanish rule in Cuba was not due to mere jingoism, although "the democratic ideals and humanitarianism that inspired their coverage are largely lost to history," as are their "heroic efforts to find the truth on the island under unusually difficult circumstances."[25] The Journal's journalistic activism in support of the Cuban rebels, rather, was centered around Hearst's political and business ambitions.[24]

Perhaps the best known myth in American journalism is the claim, without any contemporary evidence, that the illustrator Frederic Remington, sent by Hearst to Cuba to cover the Cuban War of Independence,[24] cabled Hearst to tell him all was quiet in Cuba. Hearst, in this canard, is said to have responded, "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."[26][27]

Hearst was personally dedicated to the cause of the Cuban rebels, and the Journal did some of the most important and courageous reporting on the conflict—as well as some of the most sensationalized. Their stories on the Cuban rebellion and Spain's atrocities on the island—many of which turned out to be untrue[24]—were motivated primarily by Hearst's outrage at Spain's brutal policies on the island. These had resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent Cubans. The most well-known story involved the imprisonment and escape of Cuban prisoner Evangelina Cisneros.[24][28]

While Hearst and the yellow press did not directly cause America's war with Spain, they inflamed public opinion in New York City to a fever pitch. New York's elites read other papers, such as the Times and Sun, which were far more restrained. The Journal and the World were local papers oriented to a very large working class audience in New York City. They were not among the top ten sources of news in papers in other cities, and their stories did not make a splash outside New York City.[29] Outrage across the country came from evidence of what Spain was doing in Cuba, a major influence in the decision by Congress to declare war. According to a 21st-century historian, war was declared by Congress because public opinion was sickened by the bloodshed, and because leaders like McKinley realized that Spain had lost control of Cuba.[30] These factors weighed more on the president's mind than the melodramas in the New York Journal.[31]

Hearst sailed to Cuba with a small army of Journal reporters to cover the Spanish–American War;[32] they brought along portable printing equipment, which was used to print a single-edition newspaper in Cuba after the fighting had ended. Two of the Journal's correspondents, James Creelman and Edward Marshall, were wounded in the fighting. A leader of the Cuban rebels, Gen. Calixto García, gave Hearst a Cuban flag that had been riddled with bullets as a gift, in appreciation of Hearst's major role in Cuba's liberation.[33]

Expansion

[edit]

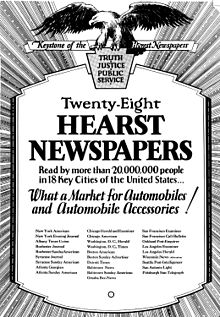

In part to aid in his political ambitions, Hearst opened newspapers in other cities, among them Chicago, Los Angeles and Boston. In 1915, he founded International Film Service, an animation studio designed to exploit the popularity of the comic strips he controlled. The creation of his Chicago paper was requested by the Democratic National Committee. Hearst used this as an excuse for his mother Phoebe Hearst to transfer him the necessary start-up funds. By the mid-1920s he had a nationwide string of 28 newspapers, among them the Los Angeles Examiner, the Boston American, the Atlanta Georgian, the Chicago Examiner, the Detroit Times, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Washington Times-Herald, the Washington Herald, and his flagship, the San Francisco Examiner.

Hearst also diversified his publishing interests into book publishing and magazines. Several of the latter are still in circulation, including such periodicals as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Town and Country, and Harper's Bazaar.

In 1924, Hearst opened the New York Daily Mirror, a racy tabloid frankly imitating the New York Daily News. Among his other holdings were two news services, Universal News and International News Service, or INS, the latter of which he founded in 1909.[34] He also owned INS companion radio station WINS in New York; King Features Syndicate, which still owns the copyrights of a number of popular comics characters; a film company, Cosmopolitan Productions; extensive New York City real estate; and thousands of acres of land in California and Mexico, along with timber and mining interests inherited from his father.

Hearst promoted writers and cartoonists despite the lack of any apparent demand for them by his readers. The press critic A. J. Liebling reminds us how many of Hearst's stars would not have been deemed employable elsewhere. One Hearst favorite, George Herriman, was the inventor of the dizzy comic strip Krazy Kat. Not especially popular with either readers or editors when it was first published, in the 21st century, it is considered a classic, a belief once held only by Hearst himself.

In 1929, he became one of the sponsors of the first round-the-world voyage in an airship, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin from Germany. His sponsorship was conditional on the trip starting at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, New Jersey. The ship's captain, Dr. Hugo Eckener, first flew the Graf Zeppelin across the Atlantic from Germany to pick up Hearst's photographer and at least three Hearst correspondents. One of them, Grace Marguerite Hay Drummond-Hay, by that flight became the first woman to travel around the world by air.[35]

The Hearst news empire reached a revenue peak about 1928, but the economic collapse of the Great Depression in the United States and the vast over-extension of his empire cost him control of his holdings. It is unlikely that the newspapers ever paid their own way; mining, ranching and forestry provided whatever dividends the Hearst Corporation paid out. When the collapse came, all Hearst properties were hit hard, but none more so than the papers. Hearst's conservative politics, increasingly at odds with those of his readers, worsened matters for the once great Hearst media chain. Having been refused the right to sell another round of bonds to unsuspecting investors, the shaky empire tottered. Unable to service its existing debts, Hearst Corporation faced a court-mandated reorganization in 1937.

From that point, Hearst was reduced to being an employee, subject to the directives of an outside manager.[36] Newspapers and other properties were liquidated, the film company shut down; there was even a well-publicized sale of art and antiquities. While World War II restored circulation and advertising revenues, his great days were over. The Hearst Corporation continues to this day as a large, privately held media conglomerate based in New York City.

Political engagement

[edit]

Hearst won two elections to Congress, then lost a series of elections. He narrowly failed in attempts to become mayor of New York City in both 1905 and 1909 and governor of New York in 1906, nominally remaining a Democrat while also creating the Independence Party. He was defeated for the governorship by Charles Evans Hughes.[37] Hearst's unsuccessful campaigns for office after his tenure in the House of Representatives earned him the unflattering but short-lived nickname of "William 'Also-Randolph' Hearst",[38] which was coined by Wallace Irwin.[39]

Hearst was on the left wing of the Progressive Movement, speaking on behalf of the working class (who bought his papers) and denouncing the rich and powerful (who disdained his editorials).[40] With the support of Tammany Hall (the regular Democratic organization in Manhattan), Hearst was elected to Congress from New York in 1902 and 1904. He made a major effort to win the 1904 Democratic nomination for president, losing to conservative Alton B. Parker.[41] Breaking with Tammany in 1907, Hearst ran for mayor of New York City under a third party of his own creation, the Municipal Ownership League. Tammany Hall exerted its utmost to defeat him.[42][43]

An opponent of the British Empire, Hearst opposed American involvement in the First World War and attacked the formation of the League of Nations. His newspapers abstained from endorsing any candidate in 1920 and 1924. Hearst's last bid for office came in 1922, when he was backed by Tammany Hall leaders for the U.S. Senate nomination in New York. Al Smith vetoed this, earning the lasting enmity of Hearst. Although Hearst shared Smith's opposition to Prohibition, he swung his papers behind Herbert Hoover in the 1928 presidential election.[44]

Move to the right and break with Franklin D. Roosevelt

[edit]During the 1920s Hearst was a Jeffersonian democrat. He warned citizens against the dangers of big government and against unchecked federal power that could infringe on individual rights. When unemployment was near 25 percent, it appeared that Hoover would lose his bid for reelection in 1932, so Hearst sought to block the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the Democratic challenger. While continuing to oppose Smith,[44] he promoted the rival candidacy of Speaker of the House, John Nance Garner, a Texan "whose guiding motto is ‘America First'" and who, in his own words, saw “the gravest possible menace” facing the country as “the constantly increasing tendency toward socialism and communism”.[45]

At the Democratic Party Convention in 1932, with control of delegations from his own state of California and from Garner's home state of Texas, Hearst had enough influence to ensure that the triumphant Roosevelt picked Garner as his running mate. In the anticipation that Roosevelt would turn out to be, in his words, “properly conservative”, Hearst supported his election. But the rapprochement with Roosevelt did not last the year. The New Deal's program of unemployment relief, in Hearst's view, was “more communistic than the communist” and “un-American to the core”.[44] More and more often, Hearst newspapers supported business over organized labor and condemned higher income tax legislation.[46]

Hearst broke with FDR in spring 1935 when the president vetoed the Patman Bonus Bill for veterans and tried to enter the World Court.[47] His papers carried the publisher's rambling, vitriolic, all-capital-letters editorials, but he no longer employed the energetic reporters, editors, and columnists who might have made a serious attack. He reached 20 million readers in the mid-1930s. They included much of the working class which Roosevelt had attracted by three-to-one margins in the 1936 election. The Hearst papers—like most major chains—had supported the Republican Alf Landon that year.[48][49]

While campaigning against Roosevelt's policy of developing formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, in 1935 Hearst ordered his editors to reprint eyewitness accounts of the Ukrainian famine (the Holodomor, which occurred in 1932–1933).[50] These had been supplied in 1933 by Welsh freelance journalist Gareth Jones,[51][52] and by the disillusioned American Communist Fred Beal.[53] The New York Times, content with what it has since conceded was "tendentious" reporting of Soviet achievements, printed the blanket denials of its Pulitzer Prize-winning Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty.[54] Duranty, who was widely credited with facilitating the rapprochement with Moscow, dismissed the Hearst-circulated reports of man-made starvation as a politically motivated "scare story".[55]

In the articles, written by Thomas Walker, to better serve Hearst's editorial line against Roosevelt's Soviet policy the famine was "updated": the impression was created of the famine continuing into 1934. In response, Louis Fischer wrote an article in The Nation accusing Walker of "pure invention" because Fischer had been to Ukraine in 1934 and claimed that he had not seen famine. He framed the story as an attempt by Hearst to "spoil Soviet-American relations" as part of "an anti-red campaign".[56]

Position regarding Germany

[edit]According to Rodney Carlisle, "Hearst condemned the domestic practices of Nazism, but he believed that German demands for boundary revision were legitimate. While he was not pro-Nazi, he accepted more German positions and propaganda than did some other editors and publishers."[57]

With “AMERICA FIRST” emblazoned on his newspaper masthead, Hearst celebrated the “great achievement” of the new Nazi regime in Germany—a lesson to all “liberty-loving people.” In 1934, after checking with Jewish leaders,[58] Hearst visited Berlin to interview Adolf Hitler. When Hitler asked why he was so misunderstood by the American press, Hearst retorted: "Because Americans believe in democracy, and are averse to dictatorship."[59] William Randolph Hearst instructed his reporters in Germany to give positive coverage of the Nazis, and fired journalists who refused to write stories favourable of German fascism.[4] Hearst's papers ran columns without rebuttal by Nazi leader Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg,[4] and Hitler himself, as well as Mussolini and other dictators in Europe and Latin America.[60] After the systematic massive Nazi attacks on Jews known as Kristallnacht (November 9–10, 1938), the Hearst press, like all major American newspapers, blamed Hitler and the Nazis: "The entire civilized world is shocked and shamed by Germany's brutal oppression of the Jewish people," read an editorial in all Hearst papers. "You [Hitler] are making the flag of National Socialism a symbol of national savagery," read an editorial written by Hearst.[61]

During 1934, Japan / U.S. relations were unstable. In an attempt to remedy this, Prince Tokugawa Iesato travelled throughout the United States on a goodwill visit. During his visit, Prince Iesato and his delegation met with William Randolph Hearst with the hope of improving relations between the two nations.

Personal life

[edit]Millicent Willson

[edit]

In 1903, 40-year-old Hearst married Millicent Veronica Willson (1882–1974), a 21-year-old chorus girl, in New York City. The couple had five sons: George Randolph Hearst, born on April 23, 1904; William Randolph Hearst Jr., born on January 27, 1908; John Randolph Hearst, born September 26, 1909; and twins Randolph Apperson Hearst and David Whitmire (né Elbert Willson) Hearst, born on December 2, 1915.

Marion Davies

[edit]

Conceding an end to his political hopes, Hearst became involved in an affair with the film actress and comedian Marion Davies (1897–1961), former mistress of his friend Paul Block.[62] From about 1919, he lived openly with her in California. After the death of Patricia Lake (1919/1923–1993), who had been presented as Davies's "niece," her family confirmed that she was Davies's and Hearst's daughter. She had acknowledged this before her death.[63]

Millicent separated from Hearst in the mid-1920s after tiring of his longtime affair with Davies, but the couple remained legally married until Hearst's death. As a leading philanthropist, Millicent built an independent life for herself in New York City. She was active in society and in 1921 founded the Free Milk Fund for Babies. For decades, the fund provided New York's poverty-stricken families with free milk for children.[63]

California properties

[edit]George Hearst invested some of his fortune from the Comstock Lode in land. In 1865 he purchased about 30,000 acres (12,000 ha), part of Rancho Piedra Blanca stretching from Simeon Bay and reached to Ragged Point. He paid the original grantee Jose de Jesus Pico USD$1 an acre, about twice the current market price.[64] Hearst continued to buy parcels whenever they became available. He also bought most of Rancho San Simeon.[citation needed]

In 1865, Hearst bought all of Rancho Santa Rosa totaling 13,184 acres (5,335 ha) except one section of 160 acres (0.6 km2) that Estrada lived on. However, as was common with claims before the Public Land Commission, Estrada's legal claim was costly and took many years to resolve. Estrada mortgaged the ranch to Domingo Pujol, a Spanish-born San Francisco lawyer, who represented him. Estrada was unable to pay the loan and Pujol foreclosed on it. Estrada did not have the title to the land.[65] Hearst sued, but ended up with only 1,340 acres (5.4 km2) of Estrada's holdings.[citation needed]

Rancho Milpitas was a 43,281-acre (17,515 ha) land grant given in 1838 by California governor Juan Bautista Alvarado to Ygnacio Pastor.[66] The grant encompassed present-day Jolon and land to the west.[67] When Pastor obtained title from the Public Land Commission in 1875, Faxon Atherton immediately purchased the land. By 1880, the James Brown Cattle Company owned and operated Rancho Milpitas and neighboring Rancho Los Ojitos.

In 1923, Newhall Land sold Rancho San Miguelito de Trinidad and Rancho El Piojo to William Randolph Hearst.[68] In 1925, Hearst's Piedmont Land and Cattle Company bought Rancho Milpitas and Rancho Los Ojitos (Little Springs) from the James Brown Cattle Company.[69] Hearst gradually bought adjoining land until he owned about 250,000 acres (100,000 ha).[70]

Fort Hunter Liggett

[edit]On December 12, 1940, Hearst sold 158,000 acres (63,940 ha), including the Rancho Milpitas, to the United States government.[71] Neighboring landowners sold another 108,950 acres (44,091 ha) to create the 266,950-acre (108,031 ha) Hunter Liggett Military Reservation troop training base for the War Department. The US Army used a ranch house and guest lodge named The Hacienda as housing for the base commander, for visiting officers, and for the officers' club.[71][72]

Little Sur River

[edit]In 1916, the Eberhard and Kron Tanning Company of Santa Cruz purchased land from the homesteaders along the Little Sur River. They harvested tanbark oak and brought the bark out on mules and crude wooden sleds known as "go-devils" to Notleys Landing at the mouth of Palo Colorado Canyon, where it was loaded via cable onto ships anchored offshore. Hearst was interested in preserving the uncut, abundant redwood forest, and on November 18, 1921, he purchased the land from the tanning company for about $50,000.[73] On July 23, 1948, the Monterey Bay Area Council of the Boy Scouts of America purchased the property, originally 1,445 acres (585 ha), from the Hearst Sunical Land and Packing Company for $20,000. On September 9, 1948, Albert M. Lester of Carmel obtained a grant for the council of $20,000 from Hearst through the Hearst Foundation of New York City, offsetting the cost of the purchase.[74]

Hearst Castle

[edit]

Beginning in 1919, Hearst began to build Hearst Castle, which he never completed, on the 250,000-acre (100,000-hectare; 1,000-square-kilometre) ranch he had acquired near San Simeon. He furnished the mansion with art, antiques, and entire historic rooms purchased and brought from great houses in Europe. He established an Arabian horse breeding operation on the grounds.

Northern California forest land

[edit]Hearst also owned property on the McCloud River in Siskiyou County, in far northern California, called Wyntoon.[a] The buildings at Wyntoon were designed by architect Julia Morgan, who also designed Hearst Castle and worked in collaboration with William J. Dodd on a number of other projects.

Beverly Hills mansion

[edit]In 1947, Hearst paid $120,000 for an H-shaped Beverly Hills mansion, (located at 1011 N. Beverly Dr.), on 3.7 acres three blocks from Sunset Boulevard. The Beverly House, as it has come to be known, has some cinematic connections. According to Hearst Over Hollywood, John and Jacqueline Kennedy stayed at the house for part of their honeymoon. The house appeared in the film The Godfather (1972).[further explanation needed][75]

In the early 1890s, Hearst began building a mansion on the hills overlooking Pleasanton, California, on land purchased by his father a decade earlier. Hearst's mother took over the project, hired Julia Morgan to finish it as her home, and named it Hacienda del Pozo de Verona.[76] After her death, it was acquired by Castlewood Country Club, which used it as their clubhouse from 1925 to 1969, when it was destroyed in a major fire.

Art collection

[edit]

Hearst was renowned for his extensive collection of international art that spanned centuries. Most notable in his collection were his Greek vases, Spanish and Italian furniture, Oriental carpets, Renaissance vestments, an extensive library with many books signed by their authors, and paintings and statues. In addition to collecting pieces of fine art, he also gathered manuscripts, rare books, and autographs.[77] His guests included varied celebrities and politicians, who stayed in rooms furnished with pieces of antique furniture and decorated with artwork by famous artists.[77]

Beginning in 1937, Hearst began selling some of his art collection to help relieve the debt burden he had suffered from the Depression. The first year he sold items for a total of $11 million. In 1941 he put about 20,000 items up for sale; these were evidence of his wide and varied tastes. Included in the sale items were paintings by van Dyke, crosiers, chalices, Charles Dickens's sideboard, pulpits, stained glass, arms and armor, George Washington's waistcoat, and Thomas Jefferson's Bible. When Hearst Castle was donated to the State of California, it was still sufficiently furnished for the whole house to be considered and operated as a museum.[77]

St Donat's Castle

[edit]After seeing photographs, in Country Life Magazine, of St. Donat's Castle in Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, Hearst bought and renovated it in 1925 as a gift to his mistress Marion Davies.[78] The Castle was restored by Hearst, who spent a fortune buying entire rooms from other castles and palaces across the UK and Europe. The Great Hall was bought from the Bradenstoke Priory in Wiltshire and reconstructed brick by brick in its current site at St. Donat's. From the Bradenstoke Priory, he also bought and removed the guest house, Prior's lodging, and great tithe barn; of these, some of the materials became the St. Donat's banqueting hall, complete with a sixteenth-century French chimney-piece and windows; also used were a fireplace dated to c. 1514 and a fourteenth-century roof, which became part of the Bradenstoke Hall, despite this use being questioned in Parliament. Hearst built 34 green and white marble bathrooms for the many guest suites in the castle and completed a series of terraced gardens which survive intact today. Hearst and Davies spent much of their time entertaining, and held a number of lavish parties attended by guests including Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Winston Churchill, and a young John F. Kennedy. When Hearst died, the castle was purchased by Antonin Besse II and donated to Atlantic College, an international boarding school founded by Kurt Hahn in 1962, which still uses it.

Interest in aviation

[edit]Hearst was particularly interested in the newly emerging technologies relating to aviation and had his first experience of flight in January 1910, in Los Angeles. Louis Paulhan, a French aviator, took him for an air trip on his Farman biplane.[79][80] Hearst also sponsored Old Glory as well as the Hearst Transcontinental Prize.

Financial disaster

[edit]Hearst's crusade against Roosevelt and the New Deal, combined with union strikes and boycotts of his properties, undermined the financial strength of his empire. Circulation of his major publications declined in the mid-1930s, while rivals such as the New York Daily News were flourishing. He refused to take effective cost-cutting measures, and instead increased his very expensive art purchases. His friend Joseph P. Kennedy offered to buy the magazines, but Hearst jealously guarded his empire and refused. Instead, he sold some of his heavily mortgaged real estate. San Simeon itself was mortgaged to Los Angeles Times owner Harry Chandler in 1933 for $600,000.[81]

Finally his financial advisors realized he was tens of millions of dollars in debt, and could not pay the interest on the loans, let alone reduce the principal. The proposed bond sale failed to attract investors when Hearst's financial crisis became widely known. Marion Davies's stardom waned and Hearst's movies also began to hemorrhage money. As the crisis deepened he let go of most of his household staff, sold his exotic animals to the Los Angeles Zoo and named a trustee to control his finances. He still refused to sell his beloved newspapers. At one point, to avoid outright bankruptcy, he had to accept a $1 million loan from Marion Davies, who sold all her jewelry, stocks and bonds to raise the cash for him.[81] Davies also managed to raise him another million as a loan from Washington Herald owner Cissy Patterson. The trustee cut Hearst's annual salary to $500,000, and stopped the annual payment of $700,000 in dividends. He had to pay rent for living in his castle at San Simeon.

Legally Hearst avoided bankruptcy although the public generally saw it as such, since appraisers went through the tapestries, paintings, furniture, silver, pottery, buildings, autographs, jewelry, and other collectibles. Items in the thousands were gathered from a five-story warehouse in New York, warehouses near San Simeon containing large amounts of Greek sculpture and ceramics, and the contents of St. Donat's. His collections were sold off in a series of auctions and private sales in 1938–39. John D. Rockefeller, Junior, bought $100,000 of antique silver for his new museum at Colonial Williamsburg. The market for art and antiques had not recovered from the depression, so Hearst made an overall loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars.[81] During this time, Hearst's friend George Loorz commented sarcastically: "He would like to start work on the outside pool [at San Simeon], start a new reservoir etc. but told me yesterday 'I want so many things but haven't got the money.' Poor fellow, let's take up a collection."[81]

He was embarrassed in early 1939 when Time magazine published a feature which revealed he was at risk of defaulting on his mortgage for San Simeon and losing it to his creditor and publishing rival, Harry Chandler.[81] This, however, was averted, as Chandler agreed to extend the repayment.

Final years and death

[edit]After the disastrous financial losses of the 1930s, the Hearst Company returned to profitability during the Second World War, when advertising revenues skyrocketed. Hearst, after spending much of the war at his estate of Wyntoon, returned to San Simeon full-time in 1945 and resumed building works. He also continued collecting, on a reduced scale. He threw himself into philanthropy by donating a great many works to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.[81]

In 1947, Hearst left his San Simeon estate to seek medical care, which was unavailable in the remote location. He died in Beverly Hills on August 14, 1951, at the age of 88.[82] He was interred in the Hearst family mausoleum at the Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California, which his parents had established.

His will established two charitable trusts, the Hearst Foundation and the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. By his amended will, Marion Davies inherited 170,000 shares in the Hearst Corporation, which, combined with a trust fund of 30,000 shares that Hearst had established for her in 1950, gave her a controlling interest in the corporation.[81] This was short-lived, as she relinquished the 170,000 shares to the Corporation on October 30, 1951, retaining her original 30,000 shares and a role as an advisor. Like their father, none of Hearst's five sons graduated from college.[83] They all followed their father into the media business, and Hearst's namesake, William Randolph Jr., became a Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaper reporter.

Criticism

[edit]In the 1890s, the already existing anti-Chinese and anti-Asian racism in San Francisco were further fanned by Hearst's anti-non-European descents, which were reflected in the rhetoric and the focus in The Examiner and one of his own signed editorials.[84] These prejudices continued to be the mainstays throughout his journalistic career to galvanize his readers’ fears.[84] Hearst staunchly supported the Japanese-American internment during WWII and used his media power to negatively portray Japanese Americans and to garner support for the internment of Japanese-Americans.[85]

Some media outlets have attempted to bring attention to Hearst's involvement in the prohibition of cannabis in the United States. Hearst collaborated with Harry J. Anslinger to ban hemp due to the threat that the burgeoning hemp paper industry posed to his major investment and market share in the paper milling industry. Due to their efforts, hemp would remain illegal to grow in the US for almost a century, not being legalized until 2018.[86][87][88]

As Martin Lee and Norman Solomon noted in their 1990 book Unreliable Sources, Hearst "routinely invented sensational stories, faked interviews, ran phony pictures and distorted real events".

Hearst's use of yellow journalism techniques in his New York Journal to whip up popular support for U.S. military adventurism in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1898 was also criticized in Upton Sinclair's 1919 book, The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism. According to Sinclair, Hearst's newspapers distorted world events and deliberately tried to discredit socialists. Another critic, Ferdinand Lundberg, extended the criticism in Imperial Hearst (1936), charging that Hearst papers accepted payments from abroad to slant the news. After the Second World War, a further critic, George Seldes, repeated the charges in Facts and Fascism (1947). Lundberg described Hearst as "the weakest strong man and the strongest weak man in the world today... a giant with feet of clay."[81]

In fiction

[edit]Citizen Kane

[edit]The film Citizen Kane (released on May 1, 1941) is loosely based on Hearst's life.[89] Welles and his collaborator, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, created Kane as a composite character, among them Harold Fowler McCormick, Samuel Insull and Howard Hughes. Hearst, enraged at the idea of Citizen Kane being a thinly disguised and very unflattering portrait of him, used his massive influence and resources to prevent the film from being released—all without even having seen it. Welles and the studio RKO Pictures resisted the pressure but Hearst and his Hollywood friends ultimately succeeded in pressuring theater chains to limit showings of Citizen Kane, resulting in only moderate box-office numbers and seriously impairing Welles's career prospects.[90] The fight over the film was documented in the Academy Award-nominated documentary, The Battle Over Citizen Kane, and nearly 60 years later, HBO offered a fictionalized version of Hearst's efforts in its original production RKO 281 (1999), in which James Cromwell portrays Hearst. Citizen Kane has twice been ranked No. 1 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies: in 1998 and 2007. In 2020, David Fincher directed Mank, starring Gary Oldman as Mankiewicz, as he interacts with Hearst prior to the writing of Citizen Kane's screenplay. Charles Dance portrays Hearst in the film.

Other works

[edit]Films

[edit]- In the television film Rough Riders (1997), Hearst (played by George Hamilton) is depicted as travelling to Cuba with a small band of journalists, to personally cover the Spanish–American War.

- Hearst is mentioned in the Disney movie Newsies (1992), directed by Kenny Ortega, which depicts the Newsboys' Strike of 1899. Hearst is never seen onscreen but is referenced by several of the newsies in various musical numbers, and is portrayed as an antagonist engaged in a bitter circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer.

- In the HBO movie Winchell (1998), Kevin Tighe played Hearst.

- In RKO 281(1999), Hearst was played by James Cromwell.

- The Cat's Meow (2001), a fictitious version of the death of Thomas H. Ince, takes place in November 1924, on a weekend cruise aboard Hearst's yacht, celebrating Ince's 44th birthday. The film's fictionalizes Ince's death by suggesting that Hearst shot Ince and covered it up.[91] Hearst is portrayed by Edward Herrmann. (Ince actually became severely ill aboard Hearst's private yacht, and the official cause of the filmmaker's death was heart failure.[92])

- He was portrayed by Matthew Marsh in Agnieszka Holland's 2019 film Mr Jones.

- He was portrayed by Charles Dance in David Fincher's 2020 film Mank.

- He was portrayed by Pat Skipper in Damien Chazelle's 2022 film Babylon.

Literature

[edit]- John Dos Passos's novel The Big Money (1936) includes a biographical sketch of Hearst.

- Jack London's futuristic, dystopian novel The Iron Heel (1908) refers to Hearst by name; and the plot "predicts" the destruction of his publishing empire (along with the Democratic Party) in 1912 by means of an oligarchy of plutocrats and industrial trusts engineering the cessation of his advertising revenue.

- In Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead (1943) and its eponymous 1949 film adaptation, the character Gail Wynand, a newspaper magnate who thinks he can control public sentiment but in reality is only a servant of the masses, is inspired by and modeled after the life of Hearst.[93]

- In John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Hearst is anonymously described as the "newspaper fella near the coast" who "got a million acres" and looks "crazy an' mean" in pictures (ch. 18).

- In Gore Vidal's historic novel series, Narratives of Empire, Hearst is a major character.

- Cormac McCarthy's novel The Crossing (1994) refers to Hearst by name and workers at his million-acre ranch in Chihuahua, La Babícora, act as antagonists in the story.

- Scott Westerfeld's novel Goliath (2011) depicts Hearst in World War I.

- In Charlaine Harris' The Russian Cage (2021), Hearst was the ruler of the HRE (formerly west coast states of US) who permitted the tsar and his entourage to settle in the defunct Navy base at San Diego.

Television

[edit]- The rivalry between Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer has been documented on National Geographic Channel's series American Genius (2015).

- In the TNT series The Alienist, in the second season played by Matt Letscher.

- In "The Paper Dynasty" (1964) episode of the syndicated Western television series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. In the story line, Hearst (played by James Hampton) struggles to turn a profit despite increased circulation of The San Francisco Examiner, featuring James Lanphier (1920–1969) as Ambrose Bierce and Robert O. Cornthwaite as Sam Chamberlain.[94]

- In "The Odyssey", a 1979 episode of the television series Little House on the Prairie, Hearst (played by Bill Ewing) is depicted as a friendly and talented young San Francisco journalist.

- Hearst (portrayed by John Colton[95]) appears in the season 2 episode "Hollywoodland" of the NBC series Timeless.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Wyntoon is located at approximately 41°11′21″N 122°03′58″W / 41.18917°N 122.06611°W

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Hearst" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Brewer, Mark (September 21, 2021). "The Man Who Built the Nation's Largest Media Empire by the 1930s, "Citizen Hearst" on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: Part Two TONIGHT at 9 p.m." WOUB Public Media. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ Rodney Carlisle, "The Foreign Policy Views of an Isolationist Press Lord: W. R. Hearst & the International Crisis, 1936–41" Journal of Contemporary History (1974) 9#3 pp. 217–27.

- ^ a b c Parenti, Michael (1997). Blackshirts & Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism. San Francisco: City Lights Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-87286-329-3.

- ^ The Battle Over Citizen Kane Archived March 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, PBS.

- ^ Betit, Kyle J. "Scots-Irish in Colonial America". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Robinson 1991, p. 33.

- ^ The American Pageant: A History of the Republic, Thirteenth edition, Advanced Placement Edition, 2006[page needed]

- ^ "Hearst Castle National Park Service". November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 463.

- ^ "The Press: The King Is Dead". Time. August 20, 1951. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ "James Montague, Versifier, Is Dead," New York Times, December 17, 1941.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 116–17.

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 100–06, 110–11, 346–48.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 314.

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 455, 463.

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 164–65, 178.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 193.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 270–74, 378.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e PBS. "Crucible of Empire: The Spanish–American War". PBS. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 260.

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (2003). Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies. p. 72.

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (December 2001). "You Furnish the Legend, I'll Furnish the Quote". American Journalism Review.

- ^ William Thomas Stead. "A Romance of the Pearl of the Antilles". Review of Reviews.

- ^ Ted Curtis Smythe, The Gilded Age Press, 1865–1900 (2003) p. 191.

- ^ Thomas M. Kane, Theoretical Roots of US Foreign Policy (2006) p. 64

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 133.

- ^ "Crucible of Empire - PBS Online". www.pbs.org. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 427.

- ^ "The Press: New York, May 24 (UPI)". Time. June 2, 1958. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles to Lakehurst". Time. September 9, 1929. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ "The Press: American's End". Time. July 5, 1937. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ "William Randolph Hearst | American newspaper publisher". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Edson, Charles Leroy (1920). The Gentle Art of Columning: A Treatise on Comic Journalism. Brentano's. p. 34.

- ^ "Wallace and Will Irwin". Interesting People. The American Magazine. March 1912. p. 545. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Roy Everett Littlefield, III, William Randolph Hearst: His Role in American Progressivism (1980)

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 168–82.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 163, 172, 195–201, 205.

- ^ Ben H. Procter, William Randolph Hearst: the early years, 1863–1910 (1998) ch 8–11

- ^ a b c Posner, Russell M. (1960). "California's Role in the Nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt". California Historical Society Quarterly. 39 (2): 121–39. doi:10.2307/25155325. JSTOR 25155325.

- ^ Rauchway, Eric (May 6, 2016). "How 'America First' Got Its Nationalistic Edge". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Procter, Ben (2007). William Randolph Hearst: The Later Years, 1911–1951. Oxford UP. p. 248. ISBN 978-0195325348.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 511–14.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. xiv, 515–17.

- ^ Rodney P. Carlisle, "William Randolph Hearst: A Fascist Reputation Reconsidered," Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 50#1 (1973): 125–33.

- ^ Commentary Bk (1983). "The Famine the "Times" Couldn't Find". Commentary. November: n. 3.

- ^ "Welsh journalist who exposed a Soviet tragedy". Wales Online, Western Mail and the South Wales Echo. November 13, 2009.

- ^ "Famine Exposure: Newspaper Articles relating to Gareth Jones' trips to The Soviet Union (1930–35)". garethjones.org. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ Mark, Brown (November 13, 2009). "1930s journalist Gareth Jones to have story retold". The Guardian. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "The New York Times Statement About 1932 Pulitzer Prize Awarded to Walter Duranty". The New York Times Company. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Gamache, Ray (2014). "Breaking Eggs for a Holodomor: Walter Duranty, the New York Times , and the Denigration of Gareth Jones". Journalism History. 39 (4): 208–218. doi:10.1080/00947679.2014.12062918. ISSN 0094-7679. S2CID 142098495.

- ^ Mace, James E. (1988). "The Politics of Famine: American Government and Press Response to the Ukrainian Famine, 1932-33" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 3 (1): 81. doi:10.1093/hgs/3.1.75. PMID 20684118.

- ^ Rodney Carlisle, "The Foreign Policy Views of an Isolationist Press Lord: W. R. Hearst and the International Crisis, 1936-41" Journal of Contemporary History 9#3 (1974), pp. 217-227, quote at pp 220-221. online

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 496–97.

- ^ Nagorski, Andrew (2012). Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power. Simon and Schuster. p. 176. ISBN 978-1439191026.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 470–77.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 554.

- ^ Toledo Blade: "Paul Block: Story of success" by Jack Lessenberry Archived December 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine January 9, 2013

- ^ a b Golden, Eve (2001). Golden Images: 41 Essays on Silent Film Stars. New York: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 26. ISBN 0-7864-0834-0.

- ^ Lidral, Terry (January 12, 2022). "Historic Hearst Ranch A Step Back into the 1860s". Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ George Hearst v. Domingo Pujol, 1872, Reports of Cases Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of California, Vol. 44, pp. 230-236, Bancroft-Whitney Co., San Francisco

- ^ Ogden Hoffman, 1862, Reports of Land Cases Determined in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, Numa Hubert, San Francisco

- ^ "Rancho Milpitas". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "HEARST BUYS SITE OF MISSION: 17 Miles of Conduits Constructed in 1792 on Acquired Tract". Stockton Independent. January 12, 1923. p. 4.

- ^ "Monterey County Historical Society, Local History Pages—Overview of Post-Hispanic Monterey County History". Archived from the original on May 22, 2006.

- ^ Lavender, Natasha (January 15, 2021). "The Crazy True Story Of William Randolph Hearst". Grunge.com. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b California State Military Department, The California State Military Museum. Historic California Posts: Fort Hunter Liggett. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ^ "Draft Fort Hunter Ligget Special Resource Study & Environmental Assessment: Chapter 2 Cultural Resources" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ "Conservation Plan Camp Camp Pico Blanco" (PDF). EMC Planning Group Inc. September 18, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ Young, Alfred (July 1963). "The Making of Men" (PDF). Salinas, California: Monterey Bay Area Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ ""Most expensive" U.S. home on sale". BBC News. July 11, 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ "Castlewood History – Castlewood Country Club". castlewoodcc.org. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Seely, Jana. "The Hearst Castle, San Simeon: The Diverse Collection of William Randolph Hearst". Southeastern Antiquing and Collecting Magazine. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Bevan, Nathan (August 3, 2008). "Lydia Hearst is queen of the castle". Wales on Sunday. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Aircraft, Volume 1 Archived February 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 1910

- ^ Hearst an Aviator Archived February 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Editor & Publisher, Volume 9, 1910

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kastner, Victoria (2000). Hearst Castle: The Biography of a Country House. Harry N. Abrams. p. 183.

- ^ "From the Archives: W. R. Hearst, 88, Dies in Beverly Hills" Archived December 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (original pub. August 15, 1951). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from LATimes.com September 15, 2018.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 357–58.

- ^ a b Amanda Pollak, Stephen Ives (September 27, 2021). Citizen Hearst: An American Experience Special, Part I (video with transcript) (Documentary). PBS. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Amanda Pollak, Stephen Ives (September 27, 2021). Citizen Hearst: An American Experience Special, Part II (video with transcript) (Documentary). PBS. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Amy Marie Orozco; Tina Fanucchi-Frontado (December 19, 2018). "Reefer Madness' and Other Lies". Santa Barbara Independent. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Dr. David Musto (1998). "Dr. David Musto Interview". Frontline (Interview). PBS. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Tony Newman (January 3, 2013). "Connecting the Dots: 10 Disastrous Consequences of the Drug War". HuffPost. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 528–56.

- ^ Howard, James. The Complete Films of Orson Welles. (1991). New York: Citadell Press. p. 47.

- ^ "Hollywood Confidential". Jonathan Rosenbaum. June 28, 2002. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Taves, Brian. (2012). Thomas Ince: Hollywood's Independent Producer. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3423-9. Retrieved January 10, 2016. Taves' extensive biography contains a strong rebuttal to the much rumored murder of Thomas Ince; see pp. 1–13.

- ^ Burns, Jennifer. (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford. pp. 44ff.

- ^ "The Paper Dynasty on Death Valley Days". IMDb. March 1, 1964. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ "Timeless (TV Series): "Hollywoodland" (2018): Full Cast & Crew: Full Credits". IMDb. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Carlson, Oliver (2007). Hearst – Lord of San Simeon. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-6684-4.

- Nasaw, David (2000). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-82759-0.

- Robinson, Judith (1991). The Hearsts: An American dynasty. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-383-1.

- Whyte, Kenneth (2009). The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Berkeley: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1582439853.

Further reading

[edit]- Bernhardt, Mark. "The Selling of Sex, Sleaze, Scuttlebutt, and other Shocking Sensations: The Evolution of New Journalism in San Francisco, 1887–1900." American Journalism 28#4 (2011): 111–42.

- Carlisle, Rodney. "The Foreign Policy Views of an Isolationist Press Lord: W. R. Hearst & the International Crisis, 1936–41" Journal of Contemporary History (1974) 9#3 pp. 217–27.

- Davies, Marion (1975). The Times We Had: Life with William Randolph Hearst. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-672-52112-1.

- Duffus, Robert L. (September 1922). "The Tragedy of Hearst". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV: 623–31. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- Frazier, Nancy (2001). William Randolph Hearst: Modern Media Tycoon. Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press. ISBN 1-56711-512-8.

- Goldstein, Benjamin S. “‘A Legend Somewhat Larger than Life’: Karl H. von Wiegand and the Trajectory of Hearstian Sensationalist Journalism*.” Historical Research 94, no. 265 (August 1, 2021): 629–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/hisres/htab019.

- Hearst, William Randolph Jr. (1991). The Hearsts: Father and Son. Niwot, CO: Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 1-879373-04-1.

- Kastner, Victoria, with a foreword by Stephen T. Hearst (2013). Hearst Ranch: Family, Land and Legacy. New York: H. N. Abrams. ISBN 978-1419708541.

- Kastner, Victoria, with photographs by Victoria Garagliano (2000). Hearst Castle: The Biography of a Country House. New York: H. N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810934153.

- Kastner, Victoria, with photographs by Victoria Garagliano (2009). Hearst's San Simeon: The Gardens and the Land. New York: H. N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810972902.

- Landers, James. "Hearst's Magazine, 1912–1914: Muckraking Sensationalist." Journalism History 38.4 (2013): 221.

- Leonard, Thomas C. "Hearst, William Randolph"; American National Biography Online (2000). Access Date: May 12, 2016

- Levkoff, Mary L. (2008). Hearst: The Collector. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-7283-4.

- Liebling, A.J. (1964). The Press. New York: Pantheon.

- Lundberg, Ferdinand (1936). Imperial Hearst: A Social Biography. New York: Equinox Corporative Press. ISBN 9780837129631.

- Olmsted, Kathryn S. The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler (Yale UP, 2022)online also online review

- Pizzitola, Louis (2002). Hearst Over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propaganda in the Movies. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11646-2.

- Procter, Ben H. (1998). William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19511277-6.

- Procter, Ben H. (2007). William Randolph Hearst: The Later Years, 1911–1951. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532534-8.

- St. Johns; Rogers, Adela (1969). The Honeycomb. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Swanberg, W.A. (1961). Citizen Hearst. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0684171470.

- Thomas, Evan. The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898 (2010).

- Winkler, John K. W.R. Hearst An American Phenomenon, Jonathan Cape, (1928)

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "William Randolph Hearst (id: H000429)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- The William Randolph Hearst Art Archive at Long Island University

- Guide to the William Randolph Hearst Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Hearstcastle.org: Hearst Castle at San Simeon

- William Randolph Hearst at IMDb

- William Randolph Hearst

- 1863 births

- 1951 deaths

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th-century art collectors

- 20th-century American newspaper founders

- 20th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 20th-century American politicians

- 20th-century art collectors

- American animated film producers

- American art collectors

- American collaborators with Nazi Germany

- American fascists

- American magazine founders

- American magazine publishers (people)

- American nationalists

- American newspaper chain owners

- American political party founders

- American socialites

- American white supremacists

- Burials at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park

- Businesspeople from Los Angeles

- Businesspeople from New Rochelle, New York

- Businesspeople from San Francisco

- California Democrats

- Candidates in the 1904 United States presidential election

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)

- Fake news in the United States

- Harvard College alumni

- The Harvard Lampoon alumni

- Hasty Pudding alumni

- Hearst family

- Journalistic scandals

- Landowners from California

- News agency founders

- People from Beverly Hills, California

- People from San Luis Obispo County, California

- People of the Spanish–American War

- Philanthropists from New York (state)

- Politicians from New Rochelle, New York

- Philanthropists from California

- Politicians from San Francisco

- Progressive Era in the United States

- Publishers from California

- San Francisco Examiner people

- St. Paul's School (New Hampshire) alumni

- United States Independence Party politicians

- Anti-Chinese sentiment

- Anti-Asian sentiment

- Anti–East Asian sentiment

- Former yacht owners of New York City

- Jeffersonian democracy