Kamares ware

Lead[edit]

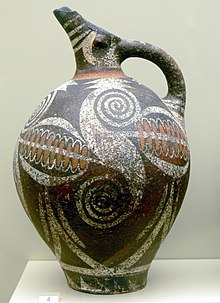

Kamares ware is a distinctive type of Minoan pottery produced in Crete during the Minoan period, dating to Middle Minoan IA period (ca. 2100 BCE). By the Late Minoan IA period (ca. 1450 BCE), or the end of the First Palace Period, these wares decline in distribution and "vitality".[1] They have traditionally been interpreted as a prestige artifact, possibly used as an elite tableware.[2]

Design and Materials[edit]

The designs of Kamares ware are typically executed in white, red and blue on a black field. Typical designs include abstract floral motifs.[3] Surviving examples include ridged cups, small, round spouted jars, and large storage jars (pithoi), on which combinations of abstract curvilinear designs and stylized plant and marine motifs are painted in white and tones of red, orange, and yellow on black grounds.[3]

Production and Trade[edit]

The Kamares style was often elaborate, with complex patterns on pottery of eggshell thinness crafted from the earliest wheeled pottery technology in the Crete region[4]. The potter's wheel was first used for Kamares ware in MM IB, and represented a watershed moment in Minoan pottery, allowing for thinner walls than was possible with handcrafted ware.[5] They were produced in the workshops of Phaistos for the upper class during the Old Palace period.[2] While they were crafted in Crete, Kamares ware were traded across the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, and have been found as far away as the Levant and Egypt.[5][6]

Historical development[edit]

The early forms of Kamares ware appeared during the Middle Minoan IA period (ca. 2100 BCE). Such pottery appeared at Knossos, in the palace's West Court, at Mochlos and Vasiliki in eastern Crete, as well as at Patrikies in the Messara Plain of southern Crete. Contemporary pottery was also found at Malia.[7]

Polychromy in a light-on-dark style already begins in this phase. This style was characterized by white and red/orange colours on a solidly painted dark ground.[3]

A relief decoration known as barbotine also appears at this time. It includes three-dimensional decorations, as well as the use of the ceramic slip. Ridges and protuberances of various types are seen on the surface of vessels.[8]

Some scholars place barbotine ware a bit earlier,

- "Barbotine Ware appears, in its earliest stages, a bit before MM IA, in EM III. The style gradually becomes more popular and picks up significantly in MM IA, along with the conservative incised style, dark on light style, and White on Dark Ware."[9]

Plenty of MM IA pottery has been found at the coastal sites of the eastern Peloponnese. Some pieces have also been found further east, on Samos and on Cyprus, as well as at Kastri, Cythera, where some Cretans had settled.[10]

Middle Minoan IB[edit]

At this time (2000-1850), large palaces are constructed at Knossos and Phaistos. The pottery found there is now made using the fast potter's wheel; this marks the beginning of the Classical Kamares style.[5]

The pots are now characterized by increasingly thinner walls, and are using more complex polychrome decorations. Some features of this pottery indicate that it was designed to appear similar to metalwork (in other words, it imitated bronze vessels).[11]

At El-Lisht, in Egypt, (near the Amenemhat I’s pyramid), several Classical Kamares sherds dating to MM IB or MM II have been found.[12] Amenemhat I belonged to the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt.[13]

Middle Minoan IIA-B[edit]

Most of these ceramics are found at the palatial sites of Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia, showing it was likely a high-prestige ware. But at most other Minoan sites, directly after MM IB comes the MM IIIA ware. A major destruction horizon is seen at Knossos and Phaistos at the end of MM IIB. This is also the time when the Protopalatial or Old Palace period ended.[14]

The finest Kamares ware is also known as eggshell ware, because of its thinness and delicacy. It was traditionally decorated with complex abstract patterns, but this period marked the first representations of stylized plants and animals. The decoration is in a light-on-dark style; white colour, and a number of shades of red, orange, and yellow were used.[14]

Middle Minoan IIIA-B[edit]

During the period around 1700 BC, the palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, and elsewhere were rebuilt. While the high quality pottery is still being produced in abundance, the artistic decoration is no longer considered a priority. This is also known as the Post-Kamares phase.[15]

At this time, Minoan influence expands throughout the southern Aegean, and reaches the Greek mainland.[16]

Different types of Kamares ware were excavated in Egypt. There are also many Egyptian imitations of Kamares ware,

- "Minoan sherds have been found at sites such as Avaris, Kahun, el-Haraga, Lisht, and Buhen. “Minoanizing” pottery has been found at Sidmant, Abydos, Aniba, Kerma, Arminna, Deir el-Medina, Gurob, and Kom Rabia’a."[16]

Gallery[edit]

Gallery of pieces from Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete.[17]

-

Kamares vases in Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Bernard Gagnon).

-

White and polychrome cup from Phaistos, 1800-1700 BC. Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Zde).

-

Polychrome dish from Phaistos, Old Palace period (1800-1700 BCE). Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Olaf Tausch).

-

Pithos with fish in a net, Phaistos (1800-1700 BCE). Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Zde).

-

Vessel from Phaistos (1800-1700 BCE). Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Zde).

-

Pithos with white palm trees on a black background (1700-1650 BCE). Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Olaf Tausch).

-

Kamares pottery, Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Zde).

-

Cups (1800-1700 BCE) from the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete (photo by Викидим).

References[edit]

- ^ Dickinson, Oliver. 1994. The Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b "The "Royal Dinner Service". Kamares Style vessels - Heraklion Archaeological Museum". 2022-04-19. Retrieved 2024-05-24.

- ^ a b c Orefice and Starry, Zack and Rachel (2009). "Kamares Ware" (PDF). University of Richmond Classics.

- ^ "Minoan Pottery". Department of Classics. 2018-06-15. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ a b c Bentancourt, Philip (1985). The History of Minoan Pottery. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Merrillees, Robert S. (2009). "The First Appearances of Kamares Ware in the Levant". Ägypten und Levante (in German). 1: 127–142. doi:10.1553/AEundL13s127. ISSN 1015-5104.

- ^ Jeremy B. Rutter, MIDDLE MINOAN CRETE - Pottery, Chronology and External Contacts. Dartmouth College -- dartmouth.edu

- ^ Horgan, C. Michael (2008). "Knossos Fieldnotes". Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ Amie S. Gluckman (2015), MINOAN BARBOTINE WARE: STYLES, SHAPES, AND A CHARACTERIZATION OF THE CLAY FABRIC. The Temple University -- temple.edu

- ^ Jeremy B. Rutter, MIDDLE MINOAN CRETE - Pottery, Chronology and External Contacts. Dartmouth College -- dartmouth.edu

- ^ Jeremy B. Rutter, MIDDLE MINOAN CRETE - Pottery, Chronology and External Contacts. Dartmouth College -- dartmouth.edu

- ^ Caitlín E. Barrett (2009), The Perceived Value of Minoan and Minoanizing Pottery in Egypt. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 22.2, 211–234. Table p. 214

- ^ "Lintel of Amenemhat I and Deities | Middle Kingdom". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ a b "Lesson 10: Narrative – Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology". sites.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ Gisela Walberg, Kamares: A Study of the Character of Palatial Middle Minoan Pottery. (Göteborg: P.Åström, 1976)

- ^ a b Davis, Amanda L. (2008). Egyptian and Minoan Relations during the Eighteenth Dynasty/Late Bronze Age. Brown University.

- ^ "Highlights - Heraklion Archaeological Museum". 2022-04-19. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

Further reading[edit]

- MacGillivray, J.A. 1998. Knossos: Pottery Groups of the Old Palace Period BSA Studies 5. (British School at Athens) ISBN 0-904887-32-4 Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2002

- Walberg, Gisela. 1986. Tradition and Innovation. Essays in Minoan Art (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp Von Zabern)

- Bentancourt, Philip (1985). The History of Minoan Pottery. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.