Aloys Wach

Aloys Wach or Aloys Ludwig Wachelmayr (sometimes Wachelmeier, 30 April 1892 – 18 April 1940) was an Austrian expressionist painter and graphic artist.[1] He was born in Lambach, Upper Austria, and died in Braunau, Upper Austria.[1][2] While his birthplaces him close to the generation that laid the foundations of modern art and especially expressionism, his life as an artist, however, began after cubism, futurism and the expressionists of the Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke movements had initiated a time of great changes. In his later life, Wach abandoned his artistic roots and distanced himself from his early expressionist works by turning to religious imagery. Today, however, those early works are seen as his greatest accomplishments.

Biography[edit]

Wach decided to become an artist early on in his life, and arrived in Vienna at the young age of 17, but initially suffered a series of setbacks. He was rejected as a student by the academy in Munich and attempted unsuccessfully to study art in Vienna. He received formal education at the Knirr-Sailer painting school in Munich as well as, in 1913, the Académie Colarossi in Paris. He finished his studies with Heinrich Altherr in Stuttgart.[1]

In 1912, he briefly moved to Berlin. There, he met painter and graphic artist Jacob Steinhardt, who encouraged him to abandon older forms of expression and be courageous in the search for his own style. Wach was also confronted with the activities at the newly opened Sturm-Galerie, the German center of expressionism. Although it is not known for certain, he also probably saw the Blaue Reiter Exhibition and the first exhibits of the futurist movement.

He then moved on to Paris, where he stayed from 1913 to 1914. He befriended Amedeo Modigliani[2] and was introduced to some of the painters at the Bateau-Lavoir. He must also have seen work by Robert Delaunay. He quickly understood the importance of the new structures in painting. In that period, he created mainly expressionist-cubist drawings, etchings and wood carvings. During his stay in Paris, he also met his most important friend and supporter, the painter and art critic, Ernest L. Tross, whom he met again in Vienna (1919) and Munich (1931).[3]

In 1915 and 1916, Wach created a series of woodcuts showing the horror of war. Postcard-size woodcuts such as Ein Totentanz von 1914 ('A Dead Dance of 1914') and Straße der Schicksale ('Road of Destiny') depict an industrialized war of detonating bullets and dying soldiers.[4] Wach served in World War I in non-combative assignments. In 1916/7, he published seven woodcuts to accompany a poem called Kriegstotentanz 1914, by an otherwise unknown poet named F.R. Zenz.

Wach, Georg Schrimpf and Fritz Schaefler were members of the short-lived but important Aktionsauschuss Revolutionärer Künstler (Action Committee of Revolutionary Artists) which formed in 1919. Wach's woodcuts appeared in connection with radical causes and drew widespread attention in the daily press, at risk to himself.[5][6][7]

From 1919 to 1920, he created the wood carving cycle "Der verlorene Sohn". From 1920 he created expressionist still lifes, landscape paintings and portraits in Braunau, but later distanced himself from paintings of this period. A set of 16 wartime etchings, "Ein Totentanz" von 1914 was published in portfolio form in 1922.[8] Following the Anschluss in 1938, Wach was banned from painting by the Nazi regime.[9] He died on 18 April 1940 of tuberculosis and malnutrition. His works were willed to Ernest Tross, who received them in Denver, Colorado in 1945.[2]

In 1956, a retrospective exhibition was held at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art, with works lent to the museum by Tross, who also wrote the catalog.[3]

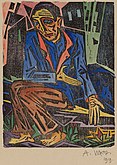

Selected paintings[edit]

-

Homage to the Christ Child

-

Woman in a Café

-

Poverty, 1919

-

Pietà, 1920

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Aloys Wach: Biography". Widder Fine Arts. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Heller, Reinhold (1991). Art in Germany, 1909-1936 : from expressionism to resistance : the Marvin and Janet Fishman collection. Milwaukee, Wis., U.S.A.: Milwaukee Art Museum. ISBN 9780944110027.

- ^ a b Alois Wach. An Exhibition of Prints and Drawings. Lent by Ernest L. Tross. (Ausst.) Sept. 4-oct. 1956, Los Angeles County Museum. Los Angeles County Museum. 1956.

- ^ Dreisbach, Martina (May 22, 2014). "Beim Totentanz verbietet sich jede Hoffnung". Taunus Zeitung. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Modern Art (Catalogue 159)" (PDF). Ars Libri Ltd. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Barron, Stephanie (1988). German Expressionism 1915-1925: The Second Generation. Los Angeles. p. 113.

- ^ Weinstein, Joan (1990). The end of expressionism : art and the November Revolution in Germany, 1918-19. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 177–187. ISBN 9780226890593. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Wach, Aloys; Deistler, M. (1922). "Ein Totentanz" von 1914 Worte zum Radierungen-Zyklus. Braunau.

- ^ "Der grausame Tanz". Frankfurter Rundschau GmbH. May 22, 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

Sources[edit]

- Assmann, Peter (1993). Aloys Wach, 1892‒1940 (Katalog zur Ausstellung Aloys Wach 1892‒1940 in der OÖ Landesgalerie vom 12.12.1993 bis zum 16.1.1994). Linz: OÖ. Landesmuseum. ISBN 978-3900746612.

- Guenther, Peter W. (1991). Aloys Wach, Paris. Munich 1914‒1919 (exhibition catalogue). New York: Brandt Dayton.

- Die Österreichischen Maler der Geburtsjahrgänge 1881‒1900. Vol. 2: M-Z, Heinrich Fuchs, Vienna 1977; OCLC 2816001

External links[edit]

- 1892 births

- 1940 deaths

- 20th-century Austrian painters

- Austrian male painters

- Austrian Expressionist painters

- Austrian expatriates in Germany

- People from Wels-Land District

- Académie Colarossi alumni

- Tuberculosis deaths in Germany

- Deaths by starvation

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- 20th-century Austrian male artists