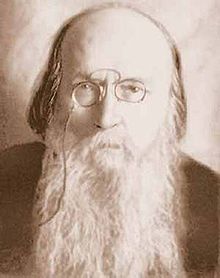

Apollon Karelin

Apollon Karelin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 23, 1863 St. Petersburg |

| Died | March 20, 1926 (aged 63) Moscow |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, activist |

Apollon Andreyevich Karelin (Russian: Аполло́н Андре́евич Каре́лин; January 23, 1863, St. Petersburg - March 20, 1926, Moscow) was a Russian anarchist.

Born into a wealthy family, Karelin became radicalized in his youth and trained as a lawyer. Passing through a series of radical political affiliations, he was subjected to political persecution, leading him to flee into exile in Paris from 1905 to 1917. There, Karelin founded a group of expatriate Russian anarchists, the Brotherhood of Free Communists (Russian: Братство вольных общинников, Bratstvo Volnykh Obshchinnikov), which numbered Volin among its members.[1][2] The Brotherhood split acrimoniously in 1913 over questions of leadership, accusations of antisemitism, and rumors of infiltration by the Okhrana.[3][4]

After the Russian Revolution, Karelin returned to Moscow. There, in 1918, he founded the All-Russian Federation of Anarchists,[5] and he became editor of its press organ, Free Life (Russian: Вольная жизнь, Volnaya Zhizn), published in Moscow from 1919 to 1921.[6] Controversially, Karelin urged anarchists to cooperate with the Bolshevik government, gaining a seat on the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.[7]

Karelin died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1926.[8]

Writings[edit]

Karelin was a prolific writer and theorist whose interests ranged from economics to mysticism.[2][9] In 1921, he published a utopia, Rossiia v 1930 godu (Russia In 1930).[10] In this novel, according to the blog Tolkovatelya,

two English travelers tell about their visit to the anarchist country [...] moving from one village-commune to another and talking with their inhabitants. These conversations are held around what Kropotkin and Karelin themselves are saying in their theoretical works: natural exchange, free distribution of labor, life in communes, based on solidarity, a union of the city and the village without forcible urbanization. The transition to an anarcho-communist system takes place without coercion. Moreover, no laws, other than ethics, regulate the life of communes. Only conviction and moral authority can influence the decision of each person. Nonviolence (as in the Tolstoy communities) is the main feature of this utopia, which distinguishes it from the general background of the revolutionary era.[11]

Bibliography[edit]

- Новое краткое изложение политической экономии (Novoye kratkoye izlozhenie politicheskoy ekonomii). New York: Izd. Soiuza russkikh rabochikh, 1918.[1]

- Общинное владение в России (Obshchinnoye vladenie v Rossii). St. Petersburg: Izd. A.S. Suvorin, 1893.[2]

- Краткое изложение политической экономии (Kratkoye izlozheniye politicheskoy ekonomii). St. Peterburg: L.F. Panteli e ev, 1894.[3]

- Земельная программа анархистов-коммунистов (Zemelnaya programma anarkhistov-kommunistov). London: Khleb i volia, 1912.

- Государство и анархисты (Gosudarstvo i anarkhisty). Moscow: Buntar, 1918.

- Злые россказни про евреев (Zlye rosskazni pro yevreyev). Moscow: Vserossiyskiy tsentr. ispolnitel'nyy komitet sovetov r.,s.,k. i k. deputatov, 1919.

- Что такое анархия? (Chto takoye anarkhiya?) Moscow: Izdanie Vseros. Federacii Anarch.-Kommunist., 1923.

- Смертная казнь (Smertnaya kazn). Detroit: Izd. Professoinalʹnogo soiuza, 1923.

- Россия в 1930 году (Rossiya v 1930 godu). Moscow: Vserossiiskaia federatsiia anarkhistov, 1921.

- Так говорил Бакунин (Tak govoril Bakunin). Buenos Aires: Golos Truda, 1921.

- Городские рабочие, крестьянство, власть и собственность (Gorodskie rabochie, krestyanstvo, vlast i sobstvennost). Buenos Aires: Izd. Rabochei Izdavatelʹskoi Gruppy v Argentine, 1924.

- Вольная жизнь (Volnaya zhizn). Detroit: Profsoiuz, 1955.[4]

Under the pseudonym "A. Kochegarov":

- Положительные и отрицательные стороны демократии с точки зрения анархистов-коммунистов (Polozhitelnye i otritsatelnye storony demokratii s tochki zreniya anarkhistov-kommunistov). Geneva: Izd. Bratstva Volʹnych Obščinnikov, 1912.[5]

- К вопросу о коммунизме (K voprosu o kommunizme). Bridgeport, Conn.: n.p., 1918.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. Edinburgh: AK Press. pp. 174–175, 137.

- ^ a b "Life of the Anarchist 'Jesuit' (Apollon Karelin) [Review]". Kate Sharpley Library. Translated by Szarapow. 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. Edinburgh: AK Press. pp. 113, 115.

- ^ Gooderham, P. (1981). The Anarchist Movement In Russia, 1905-1917 (PDF). University of Bristol. pp. 214–216, 220–221.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. Edinburgh: AK Press. p. 257.

- ^ Heller, Leonid (1996). "Voyage au pays de l'anarchie. Un itinéraire: L'utopie" [Journey to the Land of Anarchy: An Itinerary: Utopia]. Cahiers du Monde russe. 37 (3): 255. doi:10.3406/cmr.1996.2460 – via Persée.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. Edinburgh: AK Press. p. 201.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). The Russian Anarchists. Edinburgh: AK Press. p. 236.

- ^ Nalimov, V. V. (2001). "On the History of Mystical Anarchism in Russia". International Journal of Transpersonal Studies. 20: 85–98. doi:10.24972/ijts.2001.20.1.85.

- ^ Karelin, Appollon A. (1921). Rossiia V 1930 Godu. Moskva: Vserossiiskaia federatsiia anarkhistov.

- ^ "Russkiye anarkhicheskiye utopii 1920-kh" [Russian Anarchist Utopias of the 1920s]. Blog Tolkovatelya. September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2018.