Bavaria (symbol)

Bavaria is the female symbolic figure and secular patron of Bavaria and appears as a personified allegory for the state of Bavaria in various forms and manifestations. She thus represents the secular counterpart to Mary as the religious Patrona Bavariae.

In the visual arts, the colossal bronze statue in Munich is the best-known and most monumental depiction of Bavaria. It was commissioned by King Ludwig I (1786–1868) between 1843 and 1850 and stands in structural unity with the Ruhmeshalle on the edge of the slope above the Theresienwiese.

After the Baroque colossal statues of the 17th century, it is the first example of its kind from the 19th century and the first colossal statue to be made entirely of cast bronze since antiquity. It was and is a technical masterpiece.

Allegories of Bavaria[edit]

The Tellus Bavarica has been a common allegory of the "Bavarian earth" for many centuries, appearing in many different forms, including in coats of arms, on paintings, as a relief depiction, for example above house entrances, and as a statue. In public perception, Bavaria is today largely identified with the monumental statue on the Theresienwiese, but other examples can be found in public spaces. An easily accessible one can be seen in Munich's Hofgarten: The dome of the central "Dianatempel" was originally crowned by a bronze statue of Diana by Hubert Gerhard, which Hans Krumpper presumably transformed into an allegory of Bavaria in 1623 by adding an elector's hat to her helmet and placing an orb in her hand instead of a wreath of corn.[1] There is a copy on the temple today, the original is on display in the of the Munich Residence.[2]

In 1773, Bartolomeo Altomonte created parts of the Baroque decoration of the Fürstenzell monastery near Passau and placed Bavaria in the center of the ceiling fresco in the Hall of Princes. She is depicted as a queen at the moment of her coronation by an angel and surrounded by allegories of the church, trade, agriculture and the arts.

In 1805, the artist Marianne Kürzinger created a completely different version of a Bavarian state allegory in her oil painting "Gallia protects Bavaria". The picture shows a young, delicate allegory of the country in a white and blue robe, fleeing from the impending storm into the arms of the approaching Gallia, while the Bavarian lion throws itself against the threat. The depiction reflects the alliance between Bavaria and France at the time.[3] The Habsburg Emperor Francis II had threatened: "I will not take Bavaria, I will devour it."

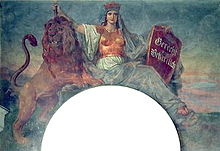

Around a quarter of a century later, Peter von Cornelius, together with other artists involved in the decoration of the Munich Hofgarten arcades, created a much more self-confident allegory of Bavaria as a fresco: this peaceful but defensive Bavaria wears a breastplate and a mural crown, in her right hand she holds an inverted spear as a sign of peace, and in her left a shield with King Ludwig I's motto "Just and Persevering". With the Bavarian Lion at her side, she sits in front of a landscape with mountains and river valleys.[4]

The unknown painter of a shooting target in Tölz from 1851[5] was almost certainly aware of Schwanthaler's work on the colossal sculpture for the Ruhmeshalle, which was already well advanced at the time, from the press or even from his own experience: Although freely interpreted, his depiction of Bavaria shows her with the same attributes as the Bavaria on the Theresienwiese, which was unveiled two years later. The clothing is different, but the positioning on the pedestal, the sword in the right hand and the victory wreath in the left clearly reveal the original. However, here the artist placed the allegory in front of an Alpine landscape with a view of Bad Tölz in the background and added a town coat of arms in the foreground.

From 2011 to 2018,[6] Bavaria, portrayed by the actress Luise Kinseher, held the sermon at the strong beer festival at Nockherberg.

Ruhmeshalle and Bavaria[edit]

The Bavaria at the Theresienwiese is surrounded by the Ruhmeshalle and the Bavariapark. It forms a conceptual and design unit, despite some breaks, with the three-winged Doric columned hall surrounding it, standing above it on its base. For this reason, the following description of the Bavaria is preceded by a brief account of the history of the hall. A more detailed account of its development can be found in the article on the Ruhmeshalle Munich.

Origin of the Ruhmeshalle[edit]

Historical background[edit]

Ludwig I's youth was marked by Napoleon's claims to power on the one hand and Austria's on the other; at the time, his family's House of Wittelsbach was a pawn between these two great powers. Until 1805, when Napoleon "liberated" Munich in the War of the Third Coalition and made Ludwig's father Maximilian king, Bavaria was repeatedly a theater of war with devastating consequences for the country. It was not until Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 that Bavaria really entered a period of peace.

In this context, Crown Prince Ludwig thought about a "Bavaria of all tribes" and a "greater German nation". These motivations and goals subsequently motivated him to undertake several construction projects for national monuments such as the Konstitutionssäule in Gaibach (1828), the Walhalla east of Regensburg above the Danube and the village of Donaustauf (1842), the Ruhmeshalle in Munich (1853) and the Befreiungshalle near Kelheim (1863), all of which were privately financed by the king and which, in terms of form and content, purpose and reception, form an artistic and political unity that is unique in Germany, despite all the internal contradictions.

Ludwig, who succeeded his father on the royal throne after his death in 1825, felt a close connection to Greece, was a fervent admirer of Greek antiquity and wanted to transform his capital Munich into an "Isar-Athens". Ludwig's second-born son Otto was proclaimed King of Greece in 1832.

Building history[edit]

As early as the time he was crown prince, Ludwig developed the plan to erect a patriotic monument in the royal seat of Munich, and subsequently had lists and directories of "great" Bavarians from all classes and professions drawn up. In 1833, he announced a competition for his building project. The competition was initially intended to gather initial ideas for the design of the Ruhmeshalle, which is why only the key data for the project were specified in the invitation to tender: The hall was to be built above the Theresienwiese and provide space for around 200 busts. The only requirement was:

"[...] this building must not become a copy of Walhalla, for as many Doric temples as there were, they were not a copy of the Parthenon [...].

This stipulation did not exclude the classicist architectural style of the parallel Walhalla project, but it is reasonable to assume that the architects were to be encouraged to propose a different architectural style. As the designs of the four participants have largely been preserved, it provides an interesting insight into the history of the Ruhmeshalle, which was built during a phase of artistic and ideological conflict between classicists on the one hand, who felt a connection to the aesthetics of Greek and Roman antiquity, and romantics on the other, who based their artistic expression on the formal language of the Middle Ages. In the competition for the Ruhmeshalle, this artistic-architectural as well as ideological-political debate continued and was reflected in the designs submitted. In March 1834, Ludwig I ultimately decided against the projects of Friedrich von Gärtner, Joseph Daniel Ohlmüller and Friedrich Ziebland, primarily for cost reasons, and commissioned Leo von Klenze to build the Ruhmeshalle. He was undoubtedly particularly impressed by the colossal statue in Klenze's design, as such a large sculpture had not been realized since antiquity. Flattered by the idea of erecting statues as imposing as the admired rulers of antiquity, Ludwig I wrote after his decision in favor of Klenze's design:[7]

"Nero and I are the only ones who have done such great things, no one since Nero."

Bavaria[edit]

Iconography[edit]

The statue was originally sketched in antique iconography, but the character was changed during the planning period. The statue that was finally created is influenced by Romanticism and incorporates the symbolism of Germanic culture.[7]

Designs by Leo von Klenze[edit]

Von Klenze drew the first sketches of a Bavaria as a "Greek Amazon" as early as 1824. The inspiration for such a statue was the colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos; several paintings from 1846 show Klenze's idea of the Acropolis of Athens.

After the competition for the design of the Ruhmeshalle was decided in v. Klenze's favor, he drew further designs for the Bavaria in addition to detailed sketches for the hall. The sketches show a Bavaria modeled on ancient depictions of the Amazon with a double-belted dress (chiton) and high-laced sandals. With her right hand, she crowns a multi-headed herm, whose four faces symbolize the virtues of rulers and war, the arts and science. In her left hand, the Bavaria holds a wreath at hip height with her arm outstretched, which she symbolically donates to the honored personalities. A lion crouches to the left of the Bavaria.

With this proposal, von Klenze created a new type of regional allegory by mixing different motifs. Personifications of Bavaria had existed long before, as described above. But while the attributes of the Tellus Bavarica on the Hofgarten temple, for example, represent the material wealth of the state, v. Klenze endowed his Bavaria with attributes of education and state leadership. In doing so, he also created a new ideal of the state. In v. Klenze's design, a virtuous and enlightened ideal of the state takes center stage and supplants the agrarian symbols. In a further design from 1834, v. Klenze planned the Bavaria as an exact copy of the Athena Promachos that once stood in front of the Acropolis. According to this proposal, the Bavaria would have been equipped with a helmet and shield and a raised lance.

On May 28, 1837, the contract for the production of the Bavaria was signed between Ludwig I, v. Klenze, the sculptor Ludwig Schwanthaler and the arch-founders Johann Baptist Stiglmaier and his nephew Ferdinand von Miller. Ludwig I and the artists involved were certainly aware of the designs for the Hermann monuments in the Teutoburg Forest from the 1820s, although these were only completed after the Bavaria.

Schwanthaler's designs[edit]

In contrast to Klenze, who was intensely interested in antiquity, Schwanthaler was a supporter of the Romantic movement and belonged to several Munich medieval circles, which were enthusiastic about everything "patriotic" but rejected anything foreign and, above all, antiquity. Schwanthaler was therefore in opposition to Klenze's classicist guidelines. It was evidently part of Ludwig's strategy to incorporate the opposing artistic views into the design of one and the same patriotic monument project in order to unite the conflicting camps under the umbrella of the nation. His attempt to synthesize the classicist and romantic-gothic styles is often referred to in the literature as "romantic classicism" or "Ludovician style".

Schwanthaler initially followed Klenze's specifications in his first Bavaria designs. However, the sculptor soon began to design his own variations of the Bavaria. The decisive factor here was his decision to no longer design the Bavaria according to the ancient model, but to dress her in a "Germanic" manner: The shirt-like dress reaching down to the feet was now draped very simply and girded together with a bearskin thrown over it, which in Schwanthaler's opinion gave the figure a typically "Teutonic" character.

In a plaster model from 1840, Schwanthaler went one step further. He now adorned Bavaria's head with an oak wreath. The wreath in her raised left hand, which Klenze had woven from laurel, also became an oak wreath. The oak was considered a particularly German tree. The redesign of the Bavaria coincided with the so-called Rhine crisis of 1840/41 and thus took place at a time of patriotic uprisings against the "arch-enemy" France. This crisis seems to have prompted Schwanthaler, who was already an enthusiastic patriot, to depict his Bavaria in an emphatically defensive manner with a drawn sword. Schwanthaler continued to modify the plaster model until 1843. In the process, the initially stiff depiction was given "inner movement" and he "succeeded in giving the compact colossal statue with its carefully suggested contrapposto position lightness and a relaxed posture. The now inclined head with milder, girlish features radiates a quiet dreaminess that was missing before. The sword is no longer held unnaturally steeply upwards, but at an angle with the right arm bent. The lion stands more unsteadily and keeps his mouth closed."[7]

In the case of the bearskin, the oak wreath and the sword, the attributes of the Bavaria are relatively easy to explain from the artistic and political context of its creation. The interpretation of the lion, however, is more difficult. Simply interpreting the animal as a symbol for Bavaria is obvious, but does not quite match Klenze's and Schwanthaler's intentions. The lion has always had a firm place in heraldry for the rulers of Bavaria. As Counts Palatine of the Rhine, the Wittelsbach dynasty had used it in their coat of arms since the High Middle Ages. In addition, two upright lions served as supporters for the Bavarian coat of arms from very early on.

However, the art historian Manfred F. Fischer is of the opinion that the lion was not only intended as Bavaria's heraldic animal alongside the Bavaria, but must also be seen as a symbol of defensiveness, just like the drawn sword.

However, the most important attribute of the Bavaria remains the oak wreath in her left hand. The wreath signifies a gift of honor for those whose busts were to be placed inside the Ruhmeshalle.

Construction[edit]

The 18.52 meter high and 1560 (Bavarian) quintals (approx. 87.36 tons) heavy statue of Bavaria was made in hollow bronze casting and consists of four partial castings (head, chest, hips, lower half and lion) and various mounted small parts. The height of the stone base is 8.92 meters.

The statue was to be cast in bronze according to v. Klenze's suggestions. Since ancient times, bronze had been considered a venerable and durable material. Ludwig, who wanted to preserve the evidence of his work for posterity, was very interested in the art of bronze casting. The king therefore supported the Munich bronze casters Johann Baptist Stiglmaier and his nephew Ferdinand von Miller and revived the long tradition of bronze casting in Munich by having a new foundry built. In 1825, the Königliche Erzgießerei on Nymphenburger Strasse, commissioned by Ludwig and built by von Klenze, was put into operation. The obelisk on Munich's Karolinenplatz, among many other large bronze sculptures of the time, was produced in this foundry.

From the end of 1839, Schwanthaler and a number of assistants gradually created a plaster model of the Bavaria in its original size on the grounds of the ore foundry. Several workshop halls caught fire during the firing process. In 1840, a first, four-meter-high auxiliary model was made. In the late summer of 1843, the completed full-size model could then be broken down into individual parts, which Stiglmaier and Miller then used as templates for the respective casting molds. However, before casting could begin, Stiglmaier died in April 1844 and the project was passed on to v. Miller.

On September 11, 1844, the head of the Bavaria was cast from the bronze of Turkish cannons that had sunk with the Egyptian-Turkish fleet in the Battle of Navarino (today Pylos on the Peloponnese) during the Greek War of Liberation in 1827 and had been raised under the Greek King Otto, son of Ludwig I, and sold as recycled material in Europe, some of which ended up in Bavaria. The arms were cast in January and March 1845, followed by the chest piece on October 11, 1845. The hip piece was cast the following year, and the entire upper part of the statue was completed in July 1848. The last major casting, for the lower section, took place on December 1, 1849.

The place where the monumental statue was made is still commemorated today by Münchner Erzgießereistraße and the parallel Sandstraße, where the sand pit required for the casting was located.

Financing[edit]

Like all of Ludwig's national monuments, the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle were private projects of the king, which he financed personally. On March 20, 1848, Ludwig I abdicated under pressure in favor of his son Maximilian, which had consequences for the continuation of the monument project. Although Maximilian promised to continue the project, his budget was only 9,000 guilders per year, which was totally insufficient.

v. Miller, who had to advance the casting costs out of his own pocket, ran into serious financial difficulties. Only when the abdicated king resumed the financing from his private coffers could the completion of the Bavaria be secured. v. Miller was left with part of the costs, but the advertising effect for the ore foundry was subsequently so great that the costs were amply offset by a large number of orders and the later privatized ore foundry was able to hold its own until the 1930s.

In total, the Ruhmeshalle cost the king 614,987 guilders, the Bavaria 286,346 guilders and the property 13,784 guilders.

Erection and inauguration in 1850[edit]

At the Oktoberfest in 1850, which would have been the 25th year of Ludwig's reign, the Bavaria was to be unveiled in a festive ceremony. Before the celebration for the abdicated king, the government's concerns had to be allayed, as it feared that such an event could be seen as a demonstration against the reigning King Maximilian II.

From June to August, the parts of the Bavaria were transported to the installation site on specially constructed carts, each pulled by twelve horses. On August 7, 1850, the head was led through the city to Theresienhöhe in a procession. The ceremonial unveiling finally took place on October 9 after a procession of all trades and guilds to Theresienwiese and, as expected, turned into a celebration of homage to the abdicated king. The artists, whom the king had greatly supported during the years of his reign and provided with commissions through his lively building activities, paid special tribute to Ludwig. In his speech after the unveiling of the Bavaria, Tischlein, who was speaking on behalf of Munich's artistic community, called out:[8]

"Thanks and praise to the present, to posterity - above all, Bavaria's honorable oak crown is due to King Ludwig the protector of art!"

The Ruhmeshalle had not yet been completed when the Bavaria was unveiled; scaffolding and wooden roofs still concealed large parts of the building. It was not until 1853 that the building was inaugurated as part of a much simpler ceremony.

Inside the statue, a spiral staircase leads up to a platform with two bronze benches and four viewing hatches. In 2014, around 33,000 visitors climbed the statue.[9] The installation of the statue on the edge of the slope above the Theresienwiese, which was much larger at the time, goes beyond the ancient references, where statues and columns referred to architecture, but instead takes up Germanic, romantic motifs: "The expanse of free, boundless space opens up before it. It belongs to the flat landscape, not to architecture" and "with the 'Bavaria', Schwanthaler succeeded in creating the first monumental Romantic work that is self-contained and yet relates to the open landscape."[7] In 1878, Georg von Hauberrisser submitted a design for the development of the eastern Theresienwiese planned from the 1870s onwards, which envisaged an oval boundary for the remaining open space, with all roads leading radially towards the Bavaria. This concept was taken up and implemented in the building line plan of 1882.[10]

Recasting of the right hand[edit]

In 1907, Oskar von Miller, the son of Ferdinand von Miller and founder of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, commissioned a faithful reproduction of the Bavaria's right hand. It was made in the Königliche Erzgießerei Ferdinand von Miller from the same material as the original (92% copper, 5% zinc, 2% tin, 1% lead). The cast has a wall thickness of 4 to 8 millimeters and weighs 420 kilograms. The hand has since been on display in the metallurgy collection of the Deutsches Museum.

Restoration[edit]

Expert examinations of the Bavaria initiated by the Bavaria 2000 association revealed such serious damage that the statue had to be closed to visitors in 2001. A total of over two thousand individual damaged areas were identified.

To partially finance the restoration work, the association produced replicas of the only Schwanthaler model, the tip of the statue's little finger in various scales, including as a drinking vessel, and other artisanal rarities, which were sold together with a publication. As a further source of funding, the outer surfaces of the scaffolding were later marketed as advertising space.

In the course of the renovation work, which was immediately initiated and cost around one million euros, not only was the raised arm extensively stabilized and the entire outer surface cleaned, sanded and sealed, but a completely new spiral staircase was also installed. The work on the statue lasted until the start of the Oktoberfest in September 2002. The base of the statue is still in need of renovation.

The Bavaria 2000 association, which under its presidents Adi Thurner and later Erwin Schneider († 2005) had campaigned for the memory of King Ludwig I and the preservation of his buildings and monuments, was dissolved in 2006.

Artistic reception[edit]

Schwanthaler's Bavaria became a model for later monuments. For example, it influenced the Swiss sculptor Ferdinand Schlöth in his St. Jakobs memorial in Basel, erected in 1872.[11]

The National Socialists had an ambivalent and cynical relationship to the Ruhmeshalle and the Bavaria.

On the one hand, they developed various plans for the redesign of the Theresienwiese fairgrounds, including the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle, which lacked any respect for the site and the intentions of its builder. In 1934, for example, the demolition of the Ruhmeshalle behind the Bavaria was considered; instead, an event area was to be built there and the Theresienwiese was to be criss-crossed by parade routes. In 1935, another plan was submitted that called for the demolition of the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle and the construction of a huge congress hall with a heroes' memorial in their place. According to the 1938 plans, the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle would remain, but would be surrounded by monumental buildings in the neoclassical style. The Theresienwiese was to be squared off.

On the other hand, the open space of the Theresienwiese and the existing representative and symbolic architecture was often used for propagandistic displays, for example for mass events at the May Day rallies, which were celebrated with great fanfare until the outbreak of war, as the following excerpt from a report in the gleichgeschaltete Presse about the celebrations on May Day 1934 shows:

"In the meantime, the enormous march to the afternoon rally on the Theresienwiese began. The march in nine giant columns began as early as 1 pm. 180,000 people streamed out of the city onto the Theresienwiese. The arrival of ten thousand members of the NS war victims' welfare service was a particularly moving sight. The huge columns from the municipal companies were personally led by mayor Fiehler. After 2 p.m., hundreds of flags from civic associations marched in, grouped together in the open square of the Ruhmeshalle. Half an hour later, the members of all the student corporations of Munich's universities marched in with their banners to line up at the foot of the columns of the Ruhmeshalle. At 3 p.m., the NSBO, the NSKBO and the student councils marched in as an immediate introduction to the festive rally. The procession was preceded by a work party with spades in their hands. The flags were placed on the steps leading up to the Bavaria and at its base. The rally itself was opened by a speech from the Gauleiter and Minister of State Adolf Wagner, who was greeted with lively cheers."[12]

Film[edit]

- König Ludwig I. und seine Bavaria, a film by Bernhard Graf, Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2018.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Larsson, Lars Olaf (1988). "Tellus Bavarica – Metamorphosen einer Landesallegorie.". Der Münchner Hofgarten – Beiträge zu einer Spurensuche (in German). Süddeutscher Verlag 1988. pp. 50–55. ISBN 3799164170.

- ^ Bavarian Palace Department : Hofgarten

- ^ Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte: Gallia schützt Bavaria, Catalog of the national exhibition 1999 "Bayern und Preussen“

- ^ Peter von Cornelius et al. (1829): "Allegorie der Bavaria" Holger Schulten"

- ^ Unknown artist (1851): "Allegorie der Bavaria mit Schwert, Kranz und Löwe, davor Wappen von Bad Tölz"

- ^ "Überraschende Ansage auf Bühne: Luise Kinseher hört als "Mama Bavaria" auf". Focus Online (in German).

- ^ a b c d Otten, Frank (1970). "Die Bavaria in München". Ludwig Michael Schwanthaler 1802–1848. Ein Bildhauer unter König Ludwig I. von Bayern (in German). Munich: Prestel-Verlag. pp. 60–64. ISBN 3791303058.

- ^ Christian Schaaf: Ruhmeshalle und die Bavaria in München als partikularstaatliches Nationaldenkmal. Term paper, submitted to the History Department of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Department of Modern and Contemporary History, in the advanced seminar with Johannes Paulmann: Die Nation zur Schau stellen. Selbstdarstellungen der Nation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, winter semester 2000/2001

- ^ Schlaier, Andrea (August 28, 2015). "Zu Kopf gestiegen". Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ Chevalley, Denis (2004). "Die städtebauliche Entwicklung in den südlichen und westlichen Stadtbereichen links der Isar". Denkmäler in Bayern – Landeshauptstadt München (in German). Munich: Südwest. pp. 65–69. ISBN 3874905845.

- ^ Hess, Stefan (1994). "Schlöth, Ferdinand". Ereignis – Mythos – Deutung 1444–1994 St. Jakob an der Birs (in German). Basel. pp. 140–164.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Der 1. Mai in München. (Press report on the Nazi May Day celebrations in Munich in 1934)". DGB Region München (in German).

Bibliography[edit]

- Otten, Frank (1972). "Die Bavaria". Denkmäler im 19. Jahrhundert (= Studien zur Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts. 20. Munich: Prestel: 107–112. ISBN 379130349X.

- Rattelmüller, Paul Ernst (1977). Die Bavaria. Geschichte eines Symbols (in German). Munich: Hugendubel. ISBN 3880340188.

- Helmut, Scharf (1985). Nationaldenkmal und nationale Frage in Deutschland am Beispiel der Denkmäler Ludwig I. von Bayern und deren Rezeption. Schnelldruckzentrum (in German). Gießen.

- Gruber, Christian.; Hölz, Christoph (1999). Erz-Zeit. Ferdinand von Miller – Zum 150. Geburtstag der Bavaria (in German). Munich: HypoVereinsbank. ISBN 3930184214.

- Fischer, Manfred F. (1997). Ruhmeshalle und Bavaria. Amtlicher Führer (in German). Munich: Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen. ISBN 3980565432.

- Kretschmar, Ulrike (1990). Der kleine Finger der Bavaria. Entstehungsgeschichte der Bavaria von Ludwig von Schwanthaler anläßlich der Auflage "Der kleine Finger der Bavaria" (Bronze-Reproduktion (in German). Offenbach am Main: Huber. ISBN 3921785537.

- Pangkofer, Josef Anselm (1850). Bavaria, Riesenstandbild aus Erz vor der Ruhmeshalle auf der Theresienwiese bei München (in German). Munich: Franz.