Beverly Deepe Keever

Beverly Deepe Keever | |

|---|---|

Keever in 1968 | |

| Born | Beverly Deepe June 1, 1935 Hebron, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Nebraska, Bachelor of Arts, Columbia University, Master of Science in Journalism University of Hawaiʻi, Master of Library and Information Studies and Doctor of Philosophy |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, author, professor |

| Notable credit(s) | Death Zones and Darling Spies: Seven Years of Vietnam War Reporting (2013), News Zero: The New York Times and The Bomb (2004), 15 U.S. News Coverage of Racial Minorities, A Sourcebook: 1934 to 1996; co-editor and chapter contributor, Top Secret: Censoring the First Rough Draft of Atomic-Bomb History,[1] Four articles based on the personal papers of Wilbur Schramm, a founder of the communications discipline,[2] Poisoning the Pacific on Nuclear Guinea Pigs,[3] Suffering Secrecy Exile,[4] Remember Enewetak,[5] Stopping the Presses: The Unprecedented Licensing of Hawaii's Media After the Attack on Pearl Harbor[6] |

| Spouse | Charles J. Keever |

Beverly Deepe Keever (born June 1, 1935) is an American journalist, Vietnam War correspondent, author and professor emerita of journalism and communications.

Beverly Deepe Keever has had a varied career that spanned the journalistic profession and professorate. Her career ranged from public opinion polling for an author-syndicated columnist in New York City, to war correspondent, to covering Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., and then to teaching and researching journalism and communications for 29 years at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

As a professor emerita and 40-some years after departing Saigon, she wrote her memoirs of covering the Vietnam War for seven years—longer than any other American correspondent as of that time. Titled Death Zones and Darling Spies, the book chronicles her dispatches as a freelancer and then successively for Newsweek, the New York Herald Tribune, The Christian Science Monitor and the London Daily Express and Sunday Express.

Her 1968 coverage of the embattled Khe Sanh Combat Base was submitted for the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting by the Christian Science Monitor. Another of her 1968 dispatches was selected by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in its centennial year as one of the 50 great stories by its alumni. In 2001, she was one of some four dozen combat correspondents whose work was selected for an exhibit at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., designed to trace 148 years of war reporting starting with the Crimean conflict of 1853. Fourteen years later, her artifacts and journalistic career were displayed and discussed in the "Reporting Vietnam" exhibit featured at the Newseum through September 2015.

She also researched and wrote News Zero: The New York Times and The Bomb.[7] Excerpts from and adaptations of this book have been published in two award-winning cover articles in Honolulu's alternative weekly and on global web sites. She is also a co-editor of 15 U.S. News Coverage of Racial Minorities: A Sourcebook, 1934-1996,[8] for which she conceptualized with others the prospectus of the volume; made arrangements with the publisher; served, in effect, as the managing editor coordinating the writing of 11 other scholars; contributed two chapters and co-authored two others.

In 1969, Beverly Deepe married Charles J. Keever.

Early life and education[edit]

Beverly Deepe was born during the worst of the Dust Bowl days in 1935[9] to Doris Widler Deepe and Martin Deepe as they struggled on his father's heavily mortgaged farm. At the Coon Ridge country school that her father had attended a generation earlier, the youngster was mesmerized upon reading Pearl S. Buck's Good Earth, which sparked her childhood dream of visiting China.[10]

She then entered the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, double majoring in journalism and political science, graduating in 1957 as Phi Beta Kappa for scholarship and Mortar Board for leadership. She went on to attend Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, graduating in 1958 with honors.

Then, working for two years in New York as an assistant to acclaimed public-opinion pollster and syndicated columnist, Samuel Lubell,[11] Beverly hoarded a modest nest egg while learning to travel light and fast, ring doorbells of voters in barometer precincts, analyze election data and develop systematic record-keeping. She carried these skills with her as she traveled to Asia.[12]

To fulfill her childhood fantasy, in 1961—a dozen years after Mao Tse-tung's army transformed the world's most populous country and a decade before the United States established diplomatic relations with it, she wrote a Ship-side View of Drab Shanghai from a Polish passenger-carrying steamer. 52 years later, she again visited Shanghai and described the dazzling changes that had transformed it with the world's tallest sky-huggers being constructed on marshland where she had seen cows grazing a half century earlier and she noted its determined push toward a "de–Americanized" world economy.[13]

She later was awarded from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa a Master's degree in Library and Information Studies and a doctorate in American Studies.

Career[edit]

Journalism[edit]

The 27-year-old Beverly Deepe arrived in South Vietnam in early 1962 just as President John F. Kennedy had initiated a new phase of an anti-communist campaign and American helicopter units and provincial advisors were unpacking. With this uptick in newsworthiness, she worked as a free-lancer without a regular paycheck, relying on her portable typewriter to write dispatches airmailed on speculation to Associated Press Newsfeatures and other media outlets. Upon her arrival, she was the sole female correspondent among the eight resident Western correspondents. When she departed Vietnam after seven years of continuous reporting, she had outlasted all of them. During that long tenure, she acquired an institutional knowledge and array of valuable local sources that few other Americans had, giving her a unique plus often lipsticked perspective.[14]

She was among the 467 women correspondents accredited by the U.S. Military command from 1965 to 1973, the years when U.S. combat units arrived and when they departed; of those 467, 267 were American. Scholars assess that with more women covering the Vietnam War than any previous U.S. conflict, it was "a turning point—to some extent a watershed—for American women as war correspondents" and in doing so, "they staked out a lasting place for their gender on the landscape of war.";[15][16]

After her arrival, she switched from dresses to fatigues and combat boots purchased in the black markets that flourished throughout Saigon. She helicoptered to Western-styled forts designed to foment communist infiltration along the Laotian border only to learn seven years later of their fall or abandonment. By Jeep and by speedboat along the waterways of the Mekong Delta, she traveled to interview embittered peasants and tenant farmers, as her own parents had been when she was born.

By 1965 with the introduction of American combat troops and squadrons of U.S. aircraft and helicopters, she trudged along soup-y rice paddies and head-high grasses to report on American and South Vietnam fighters, who often had difficulty detecting friendly folk from hide-and-seek guerrillas.

Her Vietnam War reporting included a number of notable achievements:

- Using her background of door-to-door political interviews conducted in the U.S., she became intrigued in Vietnam to learn why villagers were joining the communist enemy of the U.S.-backed Saigon government and what drove these do-or-die guerrillas or sympathizers to battle a global, nuclear-armed superpower. She wrote a number of articles probing this question over the seven years, consulting her Vietnamese assistants and numerous other sources, dissecting translations of captured documents, and interviewing pro-communists who had defected or been captured.[17]

- In 1962, she was probably the first American correspondent to write about "death zones." She used that chilling term in quoting province chief Maj. Trần Văn Minh, head of the Saigon government's Operation Sunrise that warned the rural population in pro-communist-controlled jungled areas northwest of Saigon to leave their home areas or were forcibly relocated to secured areas because the 40-square-mile pro-communist stronghold was going to be bombed and shelled.[18] The gripping "death zones" term was later sanitized by the U.S. government into the more palatable label of "free-fire zones" needed to obscure the increased number of allied airstrikes and artillery bombardments. Six years later, as President Johnson began peace negotiations in 1968, one renowned scholar noted, "further applications of massive American firepower across South Vietnam seemed likely to annihilate all too well the country the Americans had come to save."[19]

- In 1964 when working for the New York Herald Tribune, she was the first to report on the first-ever detected presence of North Vietnamese fighting units, based on her field trip to the northern city of Danang and interviews with top U.S. and South Vietnamese officers.[20] But the Pentagon and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara denied her dispatches during this politically sensitive period before the U.S. presidential elections[21] when, as a diplomat in Saigon told her American policy was "to back every status quo in sight "while trying to hold the lid on Vietnam until after the election.;[22][23] Months after the election, her articles were officially confirmed, as disclosed in the Pentagon Papers.[24]

- In 1964, her exclusive interviews with Vietnamese prime minister and military strongman Gen. Nguyễn Khánh infuriated the American Embassy in Saigon and Washington. But she also relayed his prediction that America's policy in Vietnam was so wrong-headed that "The United States will lose Southeast Asia."[25] Time described her "dust-up" with the Embassy and Khanh interviews as "a singular achievement for a girl who has yet to be accepted as a regular in Saigon's corps of foreign correspondents and who had been a Tribune correspondent for only two months," noting that she was the only U.S. reporter not regularly invited to U.S. briefings.[26][27] Within a year, Khanh was exiled; within a decade the American military and political presence had vanished from South Vietnam, paving the way for a communist take-over.

- In 1965, the New York Herald Tribune published her five-part series on the vital role Vietnamese women played on both sides of the armed conflict and provided a window on the havoc this made-by-men war was disrupting everyday life. The newspaper advertised the series as describing women "surviving amidst a savage, never-ending Holocaust.".[28]

- In 1968, during the communist country-wide blitz capturing portions of the American Embassy grounds in Saigon, overrunning dozens of provincial towns and exposing the U.S. failed search-and-destroy military strategy, she wrote that the U.S. faced the possibility of losing its first major war in its history. This front-page dispatch in The Christian Science Monitor was later selected by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, her alma mater, as one of the 50 greatest stories by its alumni in its 100-year history.

- In 1969 she was submitted for a Pulitzer Prize in international reporting by the Christian Science Monitor for her earlier coverage of the embattled Khe Sanh Combat Base while it was being bombarded by communist artillery lodged so skillfully across the border in Laotian mountains that hundreds of sorties of American strategic bombers could not silence the phantom weapons.[29] "Most of Beverly Deepe's readers presume she is a man—for her beat in Vietnam is rough, tough and dangerous," the Monitor's entry letter read. The Pulitzer Prize Committee was then told, "Yet Miss Beverly Ann Deepe, who hails from little Carleton, Nebraska, has been reporting the war and political developments from Saigon and military outposts such as Khe Sanh for seven years now. She holds her own with hosts of masculine correspondents—and asks no favors."[30]

- In 2001 she was among four dozen or so correspondents whose work had been selected for an exhibit to showcase 148 years of war reporting beginning with the Crimean conflict of 1853. Displayed at the Newseum in Washington, D.C, these "War Stories" illustrated "how correspondents deal with the challenge of reporting the facts accurately," especially when their coverage contradicts official announcements, as hers had done. Fourteen years later, her journalistic career was discussed in the "Reporting Vietnam" exhibit at the Newseum through September 12, 2015.

Academia[edit]

After Vietnam, she began teaching journalism and communications at the University of Hawaiʻi for 29 years. While teaching, she earned a master's degree in library and information studies and a PhD in American studies. She created numerous instructional materials for her students of public affairs reporting, conducted research and wrote extensively on First Amendment and freedom-of-information issues [31][32] as described in Let Us Now Praise a Lone Hawaii Voice Fighting for Open Records. She also conducted research and wrote about it that led to publication of three books.

Selected works[edit]

Deepe Keever has written a number of books, including:

- Death Zones and Darling Spies: Seven Years of Vietnam War Reporting (2013) – deals with Vietnam War reporting, based on Keever's own experiences and archival research.[33]

- News Zero: The New York Times and The Bomb (Common Courage Press, 2004)

- U.S. News Coverage of Racial Minorities: A Sourcebook, 1934-1996 (co-editor) (Greenwood Press, 1997) – Keever was co-editor of this edited volume, and also co-authored two chapters and contributed two sole-authored chapters. In one chapter titled, "The Origins and Colors of a News Gap," she found four main biases in news media coverage of racial minorities: the bias of religion and pseudo-science, the bias of the mode of communication, the bias of the legal construction of race and racism, and the bias in the nature of news.

Awards and honors[edit]

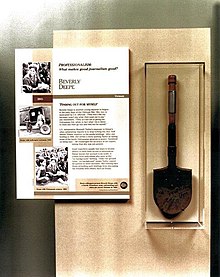

She has received the University of Hawaiʻi Regents Medal for Excellence in Teaching, numerous freedom-of-information awards and awards from the alumni associations of two of her alma maters, the University of Nebraska College of Journalism and Mass Communications and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. In March 2015 she was inducted into the Marian Andersen Nebraska Women Journalists' Hall of Fame, housed in Andersen Hall of the College of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Nebraska Lincoln campus. From May through September 12, 2015, the Newseum, blocks from the White House in Washington, included in its "Reporting Vietnam" exhibit her press card issued through the Christian Science Monitor and a North Vietnamese shovel for digging foxholes given to her by fellow correspondents upon her departure from Saigon and a description of her journalistic contributions.

External links[edit]

- Profile (archived version) from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa College of Social Sciences

References[edit]

- ^ Media History, Volume 14, Number 2, August 2008, pages 185-204.

- ^ Mass Comm Review, Volume 18, Number 1 and 2, 1991, 3-26.

- ^ Honolulu Weekly cover story, November 9-15 issue, and November 16-22 issue, 2011.

- ^ Honolulu Weekly cover story, February 25-March 2 issue, 2004, pages 4-8 and Congressional Record, March 17, 2004, H1138.

- ^ Honolulu Weekly cover story, October 30-November 5, 2002, pages 6-8.

- ^ Honolulu Weekly, December 1991, pages 3, 16.

- ^ Common Courage Press, 2004.

- ^ Greenwood Press, 1997.

- ^ Timothy Egan, The Worst Hard Times: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dustbowl (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 190.

- ^ Death Zones, pages 3-5.

- ^ Charles Poore, "Books of The Times: White and Black: Test of a Nation" The New York Times, 13 August 1964, page unavailable

- ^ Death Zones, pages 5-7.

- ^ The Future in a Dazzling Shanghai, November 8, 2013.

- ^ Death Zones, pages 10-20.

- ^ Joyce Hoffmann, On Their Own: Women Journalists and the American Experience in Vietnam, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2008), pages 5, 8, 10.

- ^ Donna Jones Born, The Reporting of American Women Foreign Correspondents from the Vietnam War, (PhD diss., Michigan State University, 1987), pages 37-41; 178-81.

- ^ Deepe, Viet Nam Report—I: Why Guerrillas Fight So Hard, New York Herald Tribune, May 30, 1965, 12 {Hereafter cited as NYHT}; Deepe, Viet Cong Wedding in the Jungle, NYHT, November 22, 1965, 2; Deepe, Our Girl in Viet—V, NYHT, June 3, 1965, page 18; Deepe, A War without a Front Line, Christian Science Monitor June 24, 1967, page 9.

- ^ On-the-scene notes made May 10, 1962 and carbon copy of two-page dispatch published in the Manila Times, as 'Death Zone' in South Vietnam, May 24, 7-A; Death Zones, p. 45-46.

- ^ Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Strategy and Policy, (New York: Macmillan, 1973, page 467.

- ^ Deepe, N. Viet troops Cross Border, U.S. Aids [sic] Say," NYHT, July 14, 1964, 4; Deepe, Viet—Measuring an Invasion," NYHT, July 26, 1964, 2.

- ^ Deepe, Viet—Measuring an Invasion," NYHT, July 26, 1964, 2.

- ^ Deepe, Viet—Measuring an Invasion, NYHT, July 26, 1964, page 2

- ^ Deepe, Viet Nam a Year after Diem: His Dire Prophecy Coming True, NYHT, November 1, 1964, page 14.

- ^ Pentagon Papers, Volume 3, pages 244, 255-57, 681.

- ^ Death Zones, pages. 126-139.

- ^ Time, "Foreign Correspondents: Self-Reliance in Saigon," January 8, 1965, page 38.

- ^ South Vietnam: The U.S. v. the Generals, NYHT, January 1, 1965, page 32-33.

- ^ The advertisement was published November 19, 1956, 15 and the five-part series began two days later

- ^ These articles are footnoted in Death Zones, page 315.

- ^ Managing editor Courtney Shelton's letter and her three-part series about embattled Khe Sanh addressed to the Advisory Board on the Pulitzer Prizes, dated December 31, 1968, is in Keever's possession at her home.

- ^ Beverly Ann Deepe Keever, "Don't let agencies fight public's right to records," Honolulu Star-Advertiser, March 21, 2012, A11

- ^ Sunshine Week Sees Abercrombie's Bill Dimming Public Access to Government Records and Meetings,

- ^ David Maguire, "Professor looks back 40 years on celebrated war reporting career[permanent dead link]," Shanghai Daily, June 2, 2013, B6