Draft:Livika

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 3 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,538 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

Comment: Comparative reading with the original source from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lounuat is needed, which I can't do. Other reviewers need to make sure context is not lost. — hako9 (talk) 23:02, 24 April 2024 (UTC)

Comment: Comparative reading with the original source from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lounuat is needed, which I can't do. Other reviewers need to make sure context is not lost. — hako9 (talk) 23:02, 24 April 2024 (UTC)

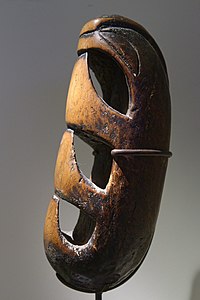

The Livika, also known as lunut, lounut, lounot, loanuat, lounuet, and also referred to as lounuat and kulepa ganez, kulepaganeg, is a friction woodblock or a friction idiophone. It is found in the Malanggan cultural region on the island of New Ireland, which is part of Papua New Guinea. Carved from a single wooden block, it features three tongues that produce clear, high-pitched tones when stroked. In the past, this instrument was utilized for religious ceremonies, and featured primarily in the mourning ritual for the deceased, its shrill cries representing either a spiritual voice or bird call.

Distribution[edit]

The island of New Ireland, situated in Melanesia, stretches over a narrow strip of about 350 kilometers from northwest to southeast between the 2nd and 5th latitudes. It is known for its Malagan ceremonies, which are large, intricate traditional cultural and funeral events that take place in parts of the island. Malangan serves as an overarching term encompassing traditional artistic creations (the style and the created objects) and the associated cult practices consisting of rituals and celebrations, specifically funeral rites. The lounuat represents a small aspect of the highly diverse wood carvings in the Malanggan style, which include standing figures (totok), two to five-meter-high statues carved from a single trunk, horizontal friezes, relief boards, animal figures, and dance masks. The Malanggan culture is confined to the northern regions of New Ireland up to the 3rd latitude, including the smaller islands of Lavongai, Dyaul, and the Tabar Island group.[1]

Augustin Kraemer (1865–1941), who extensively explored the South Seas around the turn of the century and published a book in 1925 titled Die Malanggane von Tombara (The Malanggane of Tombara), believed that the Lelet mountain region in the northern central area of New Ireland was the homeland of the lounuat. However, this assertion has not been definitively proven. In the title, by using the geographical name "Tombara," Krämer incorrectly refers to the island otherwise known at that time as Neumecklenburg, which likely stems from a misunderstanding because when questioned by Europeans, the locals responded with the word taubar, which actually means "southeast trade winds."[2] Krämer referred to the friction woodblock by the name livika, derived from vika, a term in the Oceanic language of the island's center meaning "bird" or a particular bird. Researchers at that time found that lounuat were primarily produced in a few villages in the Lelet mountains and also in the village of Hamba, located a few kilometers north in the Malanggan region.[3]

Construction[edit]

Friction idiophones form a rare group within the realm of idiophones ("self-sounding instruments"), which are set into vibration not by striking but by stroking over a smooth surface with the hand or an object. In Europe, this includes the Nail Violin, a melodic instrument where variously long iron nails are bowed with a violin bow. In America, this includes the Glass Harmonica or the musical wineglasses, which produce clear sinusoidal pitches when rubbed with moistened fingers. The Hornbostel–Sachs classification system defines the category for friction idiophones (133); the lounuat belongs in this group. Other friction vessels include the turtle shells used in rituals in Central and South America in the past. A part of the shell is smeared with resin or beeswax, and when the player strokes it with a finger or a stick, it produces a squeaking tone.[4]

The early descriptions of the lounuat are partially erroneous, and some have been uncritically adopted by later authors. Franz Hernsheim (1845–1909), one of the earliest entrepreneurs in German South Sea trade and the German consul in Jaluit, wrote in his published Südsee-Erinnerungen (1875–1880) (South Seas Memories (1875–1880)) in 1883 about the lounuat:[5]

It is a massive, round piece of wood; the upper surface is smooth and polished, intersected by 3 incisions, which widen towards the center of the wood into cavities of various sizes. Rubbing with the moist palm over the incisions produces 3 different tones. We saw such instruments up to 2 meters long and several feet in diameter.

The description is accurate; however, Hernsheim apparently confused the size with the slit drum, as such a long lounuat could not be operated by one person. The ethnologist Otto Finsch pointed out this confusion in 1914.[6] In the catalog of the collection of the Natural History Museum Vienna from 1893, Finsch describes a lounuat under the name kulegaganeg, which consists of a gently rounded soft wood measuring 40 centimeters in length and 14 centimeters in width. Finsch states the typical length as 35 to 45 centimeters, with the smallest museum specimen being a 16-centimeter-long example.[7]

Slit drums made from tree trunks, such as the garamut used in Papua New Guinea, are widespread in Melanesia and consist of several-meter-long tree trunks slit and hollowed out on one side. On New Ireland, they are ritually played by two men with long poles. A lounuat mentioned by Paul Collaer (1974) from the Royal Conservatory of Brussels is 50 centimeters long, 16 centimeters wide, and 21 centimeters high.[8] The three tongues are not rubbed with moist hands or, as Collaer indicates and Hans Oesch mistakenly adopts in the New Handbook of Musicology (1987),[9] rubbed with palm oil, as this would prevent friction and thus tone production, but with a resin sap from suitable trees such as the Papaya tree or the Breadfruit tree. This method of sound production is accurately depicted in a catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1914. The instrument listed there under the name kulepa ganez is 40 centimeters long, 13 centimeters wide, and 25 centimeters high.[10] Some lounuat are mentioned in the literature with actually four or five wooden tongues. In contrast, there are no instruments known with only two tongues, even though Jaap Kunst (1931) describes the listed "rubbing instrument" in this way. The accompanying illustration shows a typical lounuat with three tongues.[11]

Augustin Krämer (1925) describes the lounuat as a "grinding drum" and interprets a bird shape into the entire form: "The beak side, therefore the underside, has three tongues, of which the two middle ones can be interpreted as legs, and the last one as a retracted tail."[12] The approximately oval or egg-shaped outer form with its characteristic three incisions from the side also prompted other authors to interpretations. For example, Paul Collaer (1974) recognizes the shape of an animal: pangolin, anteater, or bird. A concise description is given by Hans Fischer (1958):

A wooden block ranging from 20 cm to 2 m in length (Hernsheim 106), averaging around 60 cm, is provided with three incisions in such a way that three rubbing surfaces are created over cavities open on both sides. ... The friction wood is placed longitudinally in front of the body on the ground, while the palms of the hands, rubbed with resin, are moved over the rubbing surfaces.[13]

Despite all derivations of names from birds and corresponding interpretations, it is hardly possible to recognize a bird shape in this particular form. Some authors observed further animals such as a turtle or a pig lying on its back with a trunk, two pairs of legs, and a tail in the friction wood.[14]

The production of the Livika was subject to similar rules as with the Malanggan figures and took place in secret outside the village, which is why there are no reports on the production process and the tools used. According to the outer form, the cavities are carved out and smoothed. Only then are the tongues exposed through a cut. Now the first acoustic test can take place. Further processing of the tongues serves to achieve the desired sound. The woodcarvers themselves were subject to certain behaviors and dietary regulations during production. In the beginning, students had to observe for a specified period and then precisely mimic the working method of their master.[15]

Sound Characteristics[edit]

The Livika is tuned relatively. The pitches of the three tongues were likely different regionally. Tunings and intervals mentioned in the literature are always approximations; they are not associated with tonal triads. Vocal music in the Malanggan region does not include triads. Often, the upper interval is larger than the lower one.[16]

Vibrations in friction idiophones, like in string instruments, are generated by the stick-slip effect. Slight fluctuations in pitch may occur when a tongue is rubbed precisely in the middle or slightly to the side, or depending upon what base the instrument rests. Immediately after rubbing, it is very loud and sharp in medium and large instruments, consisting almost exclusively of the fundamental pitch. Medium-sized instruments have been described as "melodic" or "bright-sounding," while large ones are described as "melodic" or "strange, eerily dark-sounding." Small friction blocks (12–20 centimeters long) produce a squeaking, scream-like sound enriched with rubbing noises. The fundamental pitch is overlaid with non-harmonic tones, yet a specific pitch is still perceptible in small instruments. The overall sound of a group of Lounuat players was influenced by the use of instruments of all three sizes and the different frequencies and intervals of the individual instruments.[17]

When Gerald Florian Messner conducted field research on New Ireland in the late 1970s, Lounuats were still occasionally made, but not executed correctly, rendering them unplayable. Frequency measurements in the laboratory showed that the rubbed and struck tongues produced almost the same pitches. Besides the fundamental pitch, these were the first overtones.[18]

Names[edit]

Numerous local names for the instruments from New Ireland were collected from the late 19th century onwards, partially translated by Siegfried Wolf (1958)[19] and Gerald Florian Messner (1980)[20]. The name "launut" was noted around the turn of the 20th century in northern New Ireland (in the Kavieng District) within the Kara language group. Pronunciation variations include "nunut" in the north, "lunuat" in Kandan on the central east coast, and "leinuat" there in the village of Lesu (according to Augustin Krämer, 1925)[21]. Additionally, "lounuot, loanuat," and "lounut" are recorded. From the island's north, "nunut" (variant "alaunut") is preserved. Bird names are said to include the word "lauka" ("dove"), which was present in the middle and north of New Ireland, and "lapka" south of Lelet. On the Lelet Plateau, according to Krämer, "livika" was common, which he derives from "vika" or "pika" for "bird." The specific bird intended could not be identified by the respondents. Krämer identifies a hornbill in the relief figure on a "lounuat," while Braunholtz (1927) finds the instrument's sound more similar to the call of a parrot.

In the northeast, a friction block of medium size (about 20 to 40 centimeters long) is called "tapárpar," which also denotes a rare brown bird with a penetrating cry. "Manu vezak" is a name recorded by Ernst Walden (1940) from Madina on the east coast in the middle north of the island, meaning "white bird,"[22] although this seems doubtful because the translation from local languages suggests "loud screeching bird" instead. Furthermore, the color white does not match the concept of a dark or nocturnal bird, rarely observed, corresponding to the mystery surrounding the "lounuat." In the Notsi-speaking village of Lesu (on the east coast, 130 kilometers south of Kavieng), Walden heard the name "vutsíngkande" for a small instrument, without providing a translation. The word context means "bird call, bird cry" and does not refer solely to the "lounuat." The compound expression "gulle bangengegg" (with spelling variations) is recorded multiple times from the northern tip of New Ireland and means "(to) go there (or up) (into the bush) to mourn (or to) lament." The numerous descriptive names are likely related to the taboo surrounding the "lounuat," whose sound was associated with the voices of the ancestors. Therefore, those not initiated into the cult, in order not to utter the name of the sacred object, chose respectful circumlocutions such as "the bird sings."

In the Madina area, Messner (1980) received Nalik-language names for various sizes of instruments: "karao" (a lizard that cries at night) for very small instruments of 12–20 centimeters in length; "manibosas" (a specific nocturnal bird) for medium-sized instruments of 25–35 centimeters; and "launut" (a bird) for large instruments of 45–60 centimeters. With the same size classification, in the village of Paruai (east coast, northern half), the names kat'kat (small brown frog, capable of leaping far and possessing a loud voice) for small instruments; "palasagáu" (a bird) for medium-sized; and "Lounuat" (large bird) for large instruments were mentioned.[23] Other names for small instruments are "qatqat" (small frog) in the Kara language, "kulekuleng" (small nocturnal bird) in the Mandara language (Tabar), and "ngutsikande" (small loud bird) in the Noatsi language; for medium instruments in Mandara "kinato" (small nocturnal bird); for large instruments in Noatsi "miluk" (large nocturnal bird), and in Mandara "ma" ("bird").[24]

Origin Stories[edit]

Due to the secrecy surrounding the "lounuat" during active cult practices, outsiders were not told origin legends about it, leading researchers to believe until the mid-20th century that there were none. Gerald Florian Messner recorded a legend in Paruai in 1977, which tells of the discovery of the Livika: Long ago, as women were gathering shells along the edge of the lagoon near the reef, one of them noticed an unusual piece of wood that seemed to have been thrown onto a reef rock jutting out of the water by the waves of the open sea. When the waves lapped against the wood, it emitted a strange sound that astonished the women. One of the women took the piece of wood and showed it to the men. From then on, the men kept it with them, copied it, and carefully hid all carved copies from women and all non-initiates.[25]

In a second legend, also learned by Messner in 1978, the Lounuat is thrown ashore by the waves and found by a woman: After a woman had plucked taro leaves for dinner, she took the leftover stalks to carry the waste in a basket to the beach and throw it into the sea. When the woman arrived at a small cliff by the sea, below which the surf rushed into a hollowed-out cave, she heard an unusual sound that frightened her. She quickly ran home and informed her husband. Curious, they both returned to the cliff, where the sound was heard again. The man was brave enough to descend to the cave, where he found the sound-producing wooden object and brought it up. He hid the wood in his house (on a shelf in the kitchen house) so that no one, especially not women, could see it. The couple asked the community to prepare a feast to celebrate the discovery of the friction block. Taro was harvested, pigs were slaughtered, and everything was prepared. At the height of the feast, the man and his wife began to rub the wood on the shelf, causing it to speak and making the people happy. Only later did the taboo for women and children arise.[26]

After the festival, the couple commissioned relatives of the woman to hide the piece of wood (called "bird") in a cave in the hills above the village. Several such "birds" were made there, for which another festival was held. For this festival, a house with leaf walls was built on the festival grounds. During the festival, 20 to 30 Lunets hidden in the house were made to ring, while one group of men danced on the ground and another group danced on a tree. At this Malanggan festival, all men had bird heads, specifically bird beaks, carved from wood in their mouths. When the Livikas sounded, the men in the tree moved in such a way that it entered into a circular vibration. At this festival, another clan bought the friction blocks and took them to a cave, where more such sticks were made, for which there was another festival, during which another clan acquired them and took them to another area.[27]

The origin legends confirm the assumption that the Lounuat, which came from the sea and was already finished, was incorporated into Malanggan cult practices in earlier times, with its sound interpreted as the voice of a spirit bird to meet the requirements of the cult. According to the second legend, the Lounuat was found by a member of a clan living in the interior, in the central highlands, confirming Augustin Krämer's hypothesis about its origin. The different figural representation also points to the stick's foreign origin for the Malanggan cult. Bird depictions on Malanggan carvings are always naturalistic, while the Livika features abstracted or ambiguously identifiable reliefs, with possible bird heads at the beak position having inappropriate teeth. The legend also states that the Lounuat was passed down ("resold") through the woman's clan. This aligns with a statement reported by Philipp Lewis in 1975, according to which the right to make this instrument was inherited through the maternal line to a male descendant.[28]

Playing technique[edit]

Regarding the use of the "lounuat," Otto Finsch (1914) writes: "The instrumentation is as simple as possible and is limited to gently stroking or rubbing the surface with a moistened hand, producing only three squeaking, not very loud tones. However, they are considered 'spirit voices,' which is why these instruments are kept taboo in the men's house."[29] In reality, the playing technique is not quite as simple. Typically, the player sits on the ground with the "lounuat" placed lengthwise between their outstretched legs. The sometimes ornamented headpiece of the instrument and the ends of the tongues extend outward from the body, so when the player strokes toward themselves starting from the headpiece with an outstretched hand, they first touch the tongue tips. The furthest tongue produces the lowest tone. Thus, the sequence is always low–medium–high. The player alternates stroking with both hands, previously rubbed with resin sap, with gentle pressure on the tongues. The order of the tones must not be changed, even though the player occasionally strokes only two tongues.

Another playing position was not reported until the mid-20th century, with one exception. Hermann Justus Braunholtz (1927) depicts a standing Malanggan figure holding a "lounuat" between its knees.[30] Gerald Florian Messner was shown this playing position by a local in 1978. A large Lounuat stood with its head on the ground and leaned against the player's thighs, who stroked upward over the tongues with both hands from below. A smaller Livika was held by the player with the headpiece about 20 centimeters above the ground and pressed between the knees, as with the Malanggan figure. Apparently, both playing positions were used in the past, possibly according to spatial constraints or cultic regulations.[31] Very small instruments could be held in one hand and stroked with the other.

Due to the secrecy regulations, Livikas were previously only used on special occasions and not, like the slit drum "garamut," for general announcements such as announcing a death or inviting to a feast. Depending on the cultic use, strictly regulated sequences of tones had to be produced. There was a repertoire of pieces for specific cultic procedures, similar to the slit drum. The sequences of tones or rhythmic structures corresponded to a thematic program for initiated listeners. The content conveyed with the Lounuat in the 1970s was, for example: 1) A man climbs a mountain quickly and breathes heavily. 2) He breaks a branch from a specific tree. 3) Two birds sing to each other alternately. The three mentioned pieces differ in rhythmic structure and the occasional rubbing of only two of the three tongues. When several (presumably 10 to 30) differently tuned instruments were played together, a very loud, penetrating overall sound was produced, which instilled fear and intimidation during the always nocturnal funeral mourning rituals. To enhance this effect, additional sound producers such as the bullroarer and tongue blades ("pekau") were used.[32]

Cultural Significance[edit]

As hinted at in the mentioned origin legend, something always had to be paid for the use of the Livika. Even students reported that they paid with shell money for practicing with the Livika. The apprenticeship ended with a consecration ritual called "malanggan-lounuat." During such a festival, the students were appointed as professional players, essentially becoming officials. The exact procedure of such a festival is not clear from historical accounts. Professional players were remunerated for their activities.[33]

The invisible use of the Livika in the bush was only possible for funeral feasts of significant men. The players had to separate themselves from the rest of the mourning community and must not be seen under any circumstances. According to one account, if someone saw a Livika player on their way into the bush, they had to be immediately killed (sacrificed), and the victim then ritually consumed. Otherwise, cannibalism is mostly claimed by others. Indigenous informants also reported that players constantly changed their location in the forest so that the voices of the ancestors sounded like they were coming from everywhere.[incomprehensible][34]

In addition to funeral feasts and the consecration festival, another festival was held where young adult men saw the Lounuat for the first time. For this purpose, the Livikas were hidden in a specially constructed house beforehand, and the young men who wanted to see them (the "birds") for the first time had to pay an entrance fee (to the "birdhouse"). There, the Lounuats were hidden under taro leaves, which a guardian pushed aside when all men were gathered. Many rules had to be observed at this festival, men and women sang songs, and there was a large feast. The significance of payment for everything related to the Livika is also evident from the stories about its production. Anyone who wanted a "lounuat" made for themselves for good reasons had to, while observing the necessary taboo regulations, obtain a piece of wood in the forest and take it to the carver, making an initial payment in the form of shell money. The final payment was made publicly as part of a festival for the handover. For this purpose, a house was also built, in which the Livika was covered by taro leaves. The man who acted as the "guardian of the bird" in the hut playfully searched for the Livika in a ritual repetition of the origin legend until he "accidentally found" it under the leaves and finally made it sound. Then the buyer made their payment. If a man who owned a Lounuat died in the past, it had to be burned with his body.[35]

Although the Lounuat and slit drum are both wooden idiophones, they differ not only in their playing technique but also in the completely different sound produced (sustained clear tones of a specific pitch vs. sequence of dull blows without a specific pitch), their own musical repertoire, and in their independently used areas. The sacred Livika were kept strictly secret, while the more profane slit drums were played outdoors and could be seen by any village member.[36]

Literature[edit]

- Rolf Bader: Outside-instrument coupling of resonance chambers in the New-Ireland friction instrument lounuet. (163rd Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America. Hong Kong, 13.–18. Mai 2012) In: Proceedings of Meetings of Acoustics, Band 15, 1. Februar 2016, S. 1–19

- Hans Fischer: Schallgeräte in Ozeanien. Bau und Spieltechnik – Verbreitung und Funktion. (Sammlung musikwissenschaftlicher Abhandlungen, Band 36) Verlag Heitz, Baden-Baden 1958 (Nachdruck: Valentin Koerner, Baden-Baden 1974)

- Gisa Jähnichen: Idiophones: Friction Instruments. In: Janet Sturman (Hrsg.): The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. Band 3: G–M, SAGE Publications, London 2019, S. 1130–1132

- Augustin Krämer: Die Málanggane von Tombára. Georg Müller, München 1925

- Gerald Florian Messner: DAS REIBHOLZ VON NEW IRELAND MANU TAGA KUL KAS... (Der "Vogel" Singt Noch...). Studien Zur Musikwissenschaft, vol. 31, 1980, pp. 221–312. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41466947.

- Waldemar Stöhr: Kunst und Kultur aus der Südsee. Sammlung Clausmeyer Melanesien. Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum für Völkerkunde, Köln 1987

Weblinks[edit]

- Surface scan of a Kulepa Ganeg. culturalheritage.digital (Hörprobe und 3D-Modell)

- Friction Drum (Lunet or Livika) late 19th–early 20th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

References[edit]

- ^ Waldemar Stöhr, 1987, p. 154

- ^ Gerhard Peekel: The Ancestral Images of North New Mecklenburg. A Critical and Positive Study. In: Anthropos, Volume 21, Issue 5/6, September–December 1926, pp. 806–824, here p. 807

- ^ Hermann Justus Braunholtz: An Ancestral Figure from New Ireland. In: Man, No. 148, December 1927, pp. 217–219, here p. 218

- ^ Edgardo Civallero: Turtle shells in traditional Latin American music. Wayrachaki editora, Bogota 2021, pp. 1–30

- ^ Franz Hernsheim: Südsee-Erinnerungen (1875–1880). A. Hofmann & Comp., Berlin 1883, p. 106

- ^ Otto Finsch: Südseearbeiten: Gewerbe- und Kunstfleiss, Tauschmittel und „Geld“ der Eingeborenen auf Grundlage der Rohstoffe und der geographischen Verbreitung. L. Friederichsen & Co., Hamburg 1914, p. 542, footnote 3

- ^ Otto Finsch: Ethnologische Erfahrungen und Belegstücke aus der Südsee. Beschreibender Katalog einer Sammlung im K.K. Naturhistorischen Hofmuseum in Wien. Alfred Hölder, Vienna 1893, pp. 58, 637

- ^ Paul Collaer: Oceania. In: Heinrich Besseler, Max Schneider (Eds.): History of Music in Pictures. Volume I: Music Ethnology. Delivery 1. 2nd edition. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1974, p. 104

- ^ Hans Oesch: Non-European Music. Part 2. (Carl Dahlhaus, Hermann Danuser (Eds.): New Handbook of Musicology, Volume 9) Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 1987, p. 369

- ^ Frances Morris: Catalogue of the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments. Volume 2: Oceania and America. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1914, p. 44

- ^ Jaap Kunst: A Study on Papuan Music. The Netherlands East Indies Committee for Scientific Research, Weltevreden 1931; reprint in: Music in New Guinea. Three Studies. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1967, p. 43, Fig. 17 on p. 60

- ^ Augustin Krämer, 1925, p. 56

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, p. 239

- ^ Curt Sachs considers a symbolic relationship of the lounuat to the pig instead of the hornbill more likely because of the pig feast during the funeral ritual, see: Curt Sachs: Geist und Werden der Musikinstrumente. (Berlin 1928) Reprint: Frits A. M. Knuf, Hilversum 1965, p. 90f, s.v. “Friction wood”

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 250–252

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, p. 257

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 275f, 295, 310

- ^ Rolf Bader, 2016, p. 3

- ^ Siegfried Wolf: Remarks on the friction blocks of New Ireland in the ethnographic museums of Dresden and Leipzig. In: Yearbook of the Museum of Ethnography in Leipzig, Volume 17, 1958, pp. 52–66

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 232–238

- ^ Augustin Krämer, 1925, p. 56

- ^ Ernst Walden, Hans Nevermann: Death ceremonies and Malagane of North-Neumecklenburg. In: Journal of Ethnology, 72nd year, issue 1/3, 1940, pp. 11–38, here p. 31

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 232–237

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner: Musical instruments: Friction blocks of New Ireland. In: Adrienne L. Kaeppler, J. W. Love (eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 9: Australia and the Pacific Islands. Routledge, New York 1998, p. 380

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 240

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 240

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 240–243

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 246–250

- ^ Otto Finsch: Südseearbeiten: Gewerbe- und Kunstfleiss, Tauschmittel und „Geld“ der Eingeborenen auf Grundlage der Rohstoffe und der geographischen Verbreitung. L. Friederichsen & Co., Hamburg 1914, p. 542

- ^ Hermann Justus Braunholtz: An Ancestral Figure from New Ireland. In: Man, No. 148, December 1927, Figure 2, p. 218

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 254–256

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 267f

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 261–264

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 270f

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 272–274

- ^ Gerald Florian Messner, 1980, pp. 265