George Marshall Clarke

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

George Marshall Clark (c. 1838 — 1861) was an African American barber in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. On September 6, 1861, Clark was forcibly taken from the city jail in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, questioned, and lynched by a crowd of fifty to seventy-five Irishmen.[1] Marshall Clark, along with another fellow African American named James P. Shelton, had exchanged insults and blows with two Irishmen who accused them of bothering two white women on the street, and Shelton ended up fatally stabbing Irishman Darby Carney.[1] Clark was eventually hanged from a pile driver later that night.[2]

Background[edit]

In Milwaukee, the Irish-American community, mostly relegated to the Historic Third Ward, was a mainly working-class community that frequently was thrown into competition with working-class African-Americans in the city.[3] Irish-Americans, though mainly blue-collar workers, often sided with the Democratic Party in the Northern United States, despite being dominated by the planter class. The two groups saw a common cause in a white supremacist politic that opposed the abolitionist and Republican press that was treated with vitriol in Democratic circles in the city.[3] Republicans themselves also carried a "disdain for Irish Catholic culture" amid their fight for African-Americans, which only heightened the hostility among Irish Democrats against African-Americans.[4]

At the time of the Civil War, lynching was not as prominent as it would become during Reconstruction and the Nadir. The Irish-American community in the city would not act purely on American traditions of violence, but Irish traditions of communal violence. Collective and illegal violence, including murder against African-Americans, was viewed as a "legitimate strategy" to maintain inequality and "subordinating African-Americans."[3]

Additionally, emotions ran high on the particular day of the lynching, as it was two days before the first anniversary of the sinking of the Lady Elgin, wherein numerous Irish-American community leaders from the city had died. Many of those leaders were members of the Milwaukee Guards, an Irish militia who opposed abolitionism and upheld the Fugitive Slave Act despite the state government, the recent memory only inflamed political tension.[4]

Lynching[edit]

While specific accounts of Marshall Clarke's interaction with a group of Irishmen in September 1861 differ, it was widely acknowledged that the central conflict arose when the Irishmen interrupted Marshall Clarke and his friend James Shelton's discussion with white women on the street. Accounts stated that the issue pertained around "the African Americans' assertion of their right to freely mix in Milwaukee's polyglot public space."[5]

The conflict quickly degenerated into a violent skirmish as Clarke and Shelton were defending their rights to act freely. Amidst the altercation, James Shelton ended up fatally stabbing one of the Irishmen, Darby Carney.[1] Following the conflict and Carney's murder, both Clarke and Shelton were put in jail, but Irish Milwaukeeans considered it was not enough.[5]

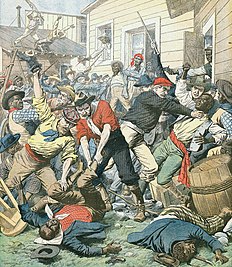

On September 6, 1861, a mob of Irishmen stormed the Milwaukee city jail to exact their revenge.[1] The mob gathered quickly after Carney's passing with the ringing of Third Wards alarm near the fire engine house their cue to gather. As quickly as the mob gathered chief of the Milwaukee police William Beck received word of the coming mob. Upon Beck's arrival, the Jailer asked whether he should open fire on the mob with his revolver if the mob broke into the jail. Beck responded that the mob would not come in "except over his body."[6] Beck with two other officers told the mob they could not enter the jail resulting in the Irish striking Beck in the head and beat the other two officers with him until depositing them in a nearby gutter.[6] Once inside the Jail the mob began to look for both Clarke and Shelton. While James Shelton was able to escape amidst the chaos, Marshall Clarke was taken by the mob, beaten, and dragged to the Third Ward's fire engine house.[1] At the fire station, Clarke was subjected to an informal trial and questioned by members of the mob.[1] Following the questioning, members of the Irish mob brutally hanged Clarke from a pile driver, and "thousands reportedly flocked to the scene of the lynching.[1] As the crowd dispersed Clarke's body was taken down by policemen who arrived on the scene and taken into the station house.[7]

Aftermath[edit]

Political unrest between the Democratic and Republican parties continued as both groups fought to place the responsibility on one another for spurring on the lynching of Marshall Clarke. [5] Democrats argued that the violence perpetrated by the Irish was appropriate but was also provoked due to the Republicans’ willingness to "rescu[e] fugitive slaves."[8] Meanwhile, the Republicans highlighted how the Irish denied any possibility of accepting the concept of African Americans having rights, including the right to due process, which was not upheld in this case.[8] Amid this turmoil, James Shelton was captured and subsequently tried for the murder of Darby Clarke, in efforts to prevent another lynching, James Shelton was transferred to Chicago to await his trial.[8] James Shelton was acquitted on a self defense plea.[8]One month later, six Irishmen that were suspected to be involved in the lynching of Marshall Clarke were tried, however, the jury could not come to a unanimous decision and the men were let go.[8]

Following these two trials, arguments between Democratic and Republican newspapers emerged once again. Republican newspaper, the Milwaukee Daily Wisconsin, criticized the local judicial system for the exoneration of the lynchers.[5] More specifically, the Daily Wisconsin highlighted the unlikelihood of the jury reaching a unanimous decision given the high probability of a pre-existing personal relationship between a juror and a defendant.[8] In turn, the Democratic counterpart, the Milwaukee News, criticized the Daily Wisconsin for not holding the same sentiment against the acquittal of James Shelton. [8] The Milwaukee News, argued that there was "three of the same jurors" present in both trials,[8] therefore implying that there was no wrongdoing. The Milwaukee News scrutinized the Daily Wisconsin for their stance on the trials as it showcased a greater importance to the murder of a "negro," than that of an "Irishman."[8]

In June 1863, two years after the lynching of Marshall Clarke, another lynching took place in Newburgh, New York at the hands of an Irish mob. The mob sought to punish African American Robert Mulliner after the alleged rape of Irishwoman Ellen Clark.[9] The mob, consisting of fifty Irishmen and supported by another several hundred Irish, gathered around the courthouse and demanded for Robert Mulliner to be turned over to them, and remained persistent after a parish priest, two judges, and the district attorney tried to convince them to let the law take its course.[9]The mob eventually invaded the courthouse and brutally beat and hanged Robert Mulliner.[9]

Significance[edit]

The lynching of Marshall Clarke is an event that highlighted the racism that persisted during the Civil War era, not only in the South but also in the North of the United States. The Northern Democratic party was thoroughly ingrained in the Irish-born population that, like their counterparts in the South, were protectors of white supremacy.[10] It is also an example of how mob violence came to be seen as a viable strategy to protect white supremacist institutions, foreshadowing the large number of lynchings that would happen during Reconstruction.

The lynchings of Marshall Clarke and Robert Mulliner, among many, also speaks to the mistreatment of both African Americans and the Irish Catholic at the time, which resulted in both groups being put in a position of resentment towards each other. On the one hand, African Americans' affiliation with the Republican Party as well as the Irish's affiliation with the Democratic Party made these racial tensions inevitable, as both groups' affiliations negatively affected the condition of the other group.[11] These lynchings also brought to light the destabilizing effects of the Civil War era on Northern politics and societal interactions; the Irish Catholics looked for ethnic vengeance because of their mistreatment, and white supremacist ideals were largely normalized in their communities and in the rest of the country.[11]

Legacy[edit]

On September 8, 2021 after nearly two centuries, Clark’s unmarked grave was memorialized with a granite headstone during a special ceremony at Forest Home Cemetery [12] in Milwaukee.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Pfeifer 2010, p. 627.

- ^ Abing 2018.

- ^ a b c Pfeifer 2010, p. 623.

- ^ a b Pfeifer 2010, p. 628.

- ^ a b c d Pfeifer 2010, p. 630.

- ^ a b Milwaukee Genealogical Society 1881, p. 300.

- ^ Milwaukee Genealogical Society 1881, p. 304.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pfeifer 2010, p. 631.

- ^ a b c Pfeifer 2010, p. 632.

- ^ Pfeifer 2010, p. 634.

- ^ a b Pfeifer 2010, p. 633.

- ^ "George Marshall Clark: Unmarked grave of Milwaukee lynching victim gets headstone after 160 years". The Milwaukee Independent. September 10, 2021.

References[edit]

- Abing, Kevin (March 21, 2018). "The Lynching of George Marshall Clark in Milwaukee". Milwaukee Independent.

- Pfeifer, Michael (December 2010). "The Northern United States and the Genesis of Racial Lynching: The Lynching of African Americans in the Civil War Era". The Journal of American History. 97 (3): 621–635. doi:10.1093/jahist/97.3.621.

- The History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin From Prehistoric Times to the Present Date... Milwaukee Genealogical Society. 1881. pp. 299–305.