Grevillea kennedyana

| Grevillea kennedyana | |

|---|---|

| |

| In the Australian National Botanic Gardens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Grevillea |

| Species: | G. kennedyana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Grevillea kennedyana | |

Grevillea kennedyana, also known as flame spider-flower,[2] is a species of flowering plant in the family Proteaceae and is endemic to a restricted area of inland eastern Australia. It is an erect shrub with many branches, usually linear leaves and erect clusters of rich red flowers.

Description[edit]

Grevillea kennedyana is an erect or sprawling, many-branched shrub that typically grows to 1.0–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 11 in) high and 2 m (6 ft 7 in) wide. Populations often consist of a close grouping of 4 to 8 individuals that have intertwining branches, creating a combined canopy of 3–5 m2 (32–54 sq ft). Individual plants have downy branches with silvery grey, linear or rarely lance-shaped leaves 7–33 mm (0.28–1.30 in) long and 1.0–1.5 mm (0.039–0.059 in) wide. The leaves are sharply-pointed and the edges are rolled under, concealing most of the lower surface. The flowers are rich red, sometimes orange-red or pink, arranged in erect groups 25–35 mm (0.98–1.38 in) long on the ends of branches with eight to twenty flowers on a rachis 2–5 mm (0.079–0.197 in) long. The flowers are glabrous to silky-hairy on the outside and softly- or shaggy-hairy inside, the pistil 27–31 mm (1.1–1.2 in) long. Flowering mainly occurs from July to November, and the fruit is a wrinkly follicle 15–19 mm (0.59–0.75 in) long, containing a winged seed 7.5–10.5 mm (0.30–0.41 in) long.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Taxonomy[edit]

Grevillea kennedyana was first formally described in 1888 by Ferdinand von Mueller in Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria from material collected by William Baeuerlen "between rocks on Grey's Ranges".[8][9] The specific epithet (kennedyana) honours "Mrs. M. B. Kennedy, of Wonnaminta".[9][10]

This grevillea is not closely related to any of Australia's others of the genus, but it does have phylogenetic resemblance to others that are found within semi-arid and temperate arid regions of south western Australia, such as G. decipiens, G. sparsiflora, and G. acuaria. Grevillea kennedyana is not well adapted to growing in deep sandy soils and as a result, the species is considered to be a relict species that has been effected by the expansions of the arid interior of Australia.[7][6]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Grevillea kennedyana has a restricted distribution in the northwest corner of New South Wales and the southwest corner of Queensland. The altitude range is 140–200 m (460–660 ft) and plants grows on slopes between 10˚ and 75˚. The area is arid and receives variable and unreliable rainfall. Plants can sometimes be found in dry and rocky watercourses, but mostly grow in clusters on rocky jump-ups and colluvial slopes of rocky mesas with weathered silcrete rocks and loamy soils. The most dense populations of this species are found on the lower slopes that have high water retention. As of 2000, the plant was found in six geographic locations. Ninety per cent of the populations are found in the Sturt National Park and are highly fragmented with a natural range of less than 100 km (62 mi)[7][6][11]

The plant communities that are found with G. kennedyana include species such as spiny fan-flower (Scaevola spinescens), whitewood (Atalaya hemiglauca), Acacia and Eremophila species, and occasionally black oak (Casuarina pauper). A low ground cover of chenopods is often present.[5][6]

Ecology[edit]

This species is capable of recruitment by rhizomes, making the current individuals clones. However, the plant has also been observed to resprout from adventitious buds from the base of the stems and seeds.[7] New growth can be stimulated by physical damage to the plant.[6]

Flowering is seen to occur 2–4 months after a major rainfall event, however during dry seasons flowering is irregular. The necessary amounts of rainfall required for flowering are not known. Fruit is believed to mature 6–8 weeks after fertilisation has occurred. The pollinators are not known, but they are believed to be birds. The seeds are then dispersed soon afterwards, however the dispersal mechanisms are still not fully understood, but it is believed to be aided by the wings that are found on the seeds.[7][6]

The period of seed dormancy is another unknown factor which needs to be investigated.[12] Depending on its similarity to other Grevillea species it is possibly that it can remain dormant for up to four years. Any recruitment that does occur via seed is believed to be event driven, relying on the combination of above average rainfall and the appropriate temperature. Seedlings that are becoming established in the summer months may be greatly affected by high temperatures and the absence of soil moisture.[7][12]

Conservation status[edit]

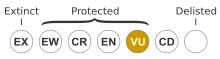

Flame spider-flower is listed as "vulnerable" under the Australian Government Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999,[2][13] the New South Wales Government Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016[7] and the Queensland Government Nature Conservation Act 1992.[14] The main threats to the species include grazing by domestic stock and invasive species, and inappropriate fire regimes.

Fire[edit]

Before European settlement in Australia, Indigenous Australians managed the land using fire. Once Europeans colonised the area these fire practices began to decline and the effect it has had on the plant is unknown. While fire is not required for G. kennedyana to release its seed, it is believed that it is required for breaking seed dormancy.[7] This needs to be properly investigated as the species does not occur in a fire prone zone.[12]

Grazing[edit]

It is possible that G. kennedyana is able to withstand browsing pressures, as it has been subjected to intensive and prolonged grazing by stock from the 1890s to the mid 20th century. Rabbits and other native macropods are also likely to browse the plant. These actions from herbivores are believed to have caused an observed lack of seedling recruitment.[7]

Seed predation[edit]

It is possible that insects, mammals and birds could be eating the seeds. Other species of Grevillea have been effected by seed predation. This is a possible contributing factor to the lack of recruitment of the species.[12]

Species ability to recover[edit]

The current known populations of G. kennedyana appear to be quite stable for the last six years that it has been monitored in the field. At present there is no known evidence to suggest that the species is significantly declining or being threatened. Also because of the species ability to persist given the heavy grazing that occurred in the park, the wild populations of the plant looks likely to remain for at least another 50–100 years. The lack of recruitment is a concern for the survival of the plant in the long-term. A possible reason for its rarity is most likely the result of natural evolutionary and ecological processes.[7]

Recovery plan[edit]

As majority of the populations of G. kennedyana reside in the Sturt National Park in NSW, the National Parks and Wildlife Service have created a recovery plan for the species. The three main objectives are to protect and monitor all known populations; find and manage the threats that are effecting the survival and recruitment of the species; and involve the community in the conservation of the species by working with the relevant landholders and managers to improve the management of identified threats to the plant.[7]

Uses[edit]

Most Grevillea species contain a honey-like liquid that is edible to humans. G. kennedyana contains a large amount of a clear, sweet liquid, which can be shaken from the flowers. However, due to the large volume of liquid it makes the flower difficult to preserve.[15]

References[edit]

- ^ "Grevillea kennedyana". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Conservation Advice Grevillea kennedyana flame spider-flower" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Makinson, Robert O. "Grevillea kennedyana". Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Grevillea kennedyana". Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment: Canberra. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Geoffrey M.; Mulham, William E.; Milthorpe, Peter L.; Leigh, John H. (1981). Plants of Western New South Wales. CSIRO Publishing.

- ^ a b c d e f Duncan, Anne (1992). "Aspects of the ecology of the rare Grevillea kennedyana (Proteaceae) in north-western New South Wales". Cunninghamia. 2 (4): 533–539. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Flame Spider Flower (Grevillea kennedyana) Recovery Plan" (PDF). New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Grevillea kennedyana". APNI. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b von Mueller, Ferdinand (1888). "Descriptions of some hitherto unknown Australian plants". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria. 24 (2): 172–173. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Finkel, Alan. "How a German migrant planted citizen science in Australia – and why it worked". theconversation.com. The Conversation Media Group Ltd. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Flame Spider Flower - profile". New South Wales Government Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d von Richter, Lotte; Azzopardi, Anthony; Johnstone, Richard; Offord, Cathy (2001). "Seed germination in the rare shrub Grevillea kennedyana (Proteaceae)". Cunninghamia. 7 (2): 205–212. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "SPRAT profile - Grevillea kennedyana - Flame Spider Flower". Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Species profile—Grevillea kennedyana". Queensland Government Department of Environment and Science. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Maiden, J. H. (1975). The useful native plants of Australia (Facsi mile Edition). Melbourne: Compendium.