Ingagi

| Ingagi | |

|---|---|

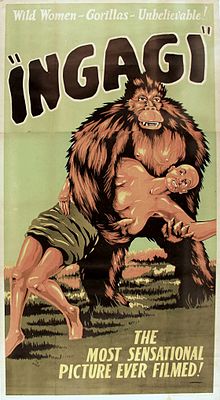

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | William S. Campbell |

| Written by | Adam Shirk |

| Produced by | William D. Alexander Nat Spitzer (executive) |

| Starring | Charlie Gemora |

| Cinematography | L. Gillingham |

| Music by | Edward Gage |

Production company | Congo Pictures |

| Distributed by | Congo Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $4 million |

Ingagi is a 1930 pre-Code pseudo-documentary exploitation film directed by William S. Campbell. It purports to be a documentary about "Sir Hubert Winstead" of London on an expedition to the Belgian Congo, and depicts a tribe of gorilla-worshipping women encountered by the explorer. The film claims to show a ritual in which African women are given over to gorillas as sex slaves, but in actuality was mostly filmed in Los Angeles, using American actresses in place of natives.[1] It was produced and distributed by Nat Spitzer's Congo Pictures, which had been formed expressly for this production.[2] Although marketed under the pretense of being ethnographic, the premise was a fabrication, leading the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association to retract any involvement.[3]

The film trades heavily on its nudity and on the suggestion of sex between a woman and a gorilla. Its success motivated RKO Radio Pictures to invest in the 1933 film, King Kong.[citation needed] RKO owned several of the theatres where Ingagi was shown, including one of the first, the Orpheum Theatre in San Francisco, where it opened April 5, 1930.[2][4]

Plot[edit]

The film starts with a text introduction, explaining the purported documentary background, then shows life aboard ship before it docks at Mombasa. They then travel inland to Nairobi, seeing African wildlife such as wildebeest on the way..

Production[edit]

Much of the footage featured in the film was taken without permission from Grace Mackenzie's 1915 film Heart of Africa, which later resulted in legal action being brought against Congo Pictures by Mackenzie's son.[2] The film purports to feature footage of a newly discovered animal, the "Tortadillo", however this animal was in fact a turtle with false wings and scales attached to it.[5] The majority of the original footage was filmed at the Griffith Park Zoo.[6]

The gorilla in the film is portrayed with a mixture of stock footage, much of which is actually footage of orangutans and chimpanzees, and actors in gorilla costumes. In October 1930, actor Charlie Gemora signed an affidavit swearing that he portrayed the gorilla.[2] Actor Hilton Phillips, originally hired to play one of the African natives in the film, alleged that he also played the gorilla. Phillips later sued Congo Pictures, claiming they failed to pay him.[7]

It was reported that Congo Pictures prepared versions of Ingagi dubbed in French, German, and Spanish.[8] Sources have claimed that the word "ingagi" cannot be found "in any African language dictionary".[2][5] "Ingagi" is in fact a Kinyarwanda word meaning "gorilla".

Release[edit]

Following the film's release, multiple articles and reviews were published that were skeptical of the film's authenticity.[9] In response, Congo Pictures filed a lawsuit against the MPPDA seeking $3,365,000 in damages, claiming that the MPPDA had "circulated reports doubting the authenticity of the film".[10]

An investigation by the Federal Trade Commission concluded that the majority of the film was "false, fraudulent, deceptive and misleading", and ordered Congo Pictures to withdraw any advertising and material from the film proclaiming it to be genuine.[5] As a result, the film was pulled from circulation. The Federal Trade Commission removed its sanction on the film in 1947.[9]

Preservation[edit]

The film was never lost, contrary to popular belief due to it long being unavailable on home video or television. Three nitrate prints are held at The Library of Congress.

Seven of the eight Vitaphone discs have been found by fans and are now available on YouTube.[11][non-primary source needed] 96 seconds of the film are included in the documentary Charlie Gemora: Uncredited.[12][non-primary source needed]

In partnership with Something Weird Video, Kino Classics released a 4K restoration of the film on Blu-ray Disc on January 5, 2021.[13]

Critical reception[edit]

Film critic Mordaunt Hall wrote in The New York Times that the film "is a loose assemblage of the usual African travel scenes, many of which are spoiled by extraordinarily bad photography," that "the screen is a miserable blur for minutes at a time," that "the scenes with gorillas last about ten minutes and are not at all convincing," but noted that "the trapping of a leopard, the capture of a giant python and a hippopotamus hunt might be genuinely interesting."[14] A contemporary review of the film in Variety reported that "photography is poor" and "the ape women are seen completely naked, but shadowed in a clearing [and] they are not as black as expected for the jungle" with "doubt concerning the naturalness of the gorilla," but noted that "there is a gripping scene when a lioness attacks a cameraman [with] no doubt of the authenticity of this frightful but vivid scene."[15]

From retrospective reviews, Michael Atkinson reviewed the home video release in Sight & Sound. Atkinson found the film "distinctive for portending to be something it absolutely is not", noting the film's litany of large animals killed and butchered and its "wall to wall" supremacist stereotypes, while finding the footage taken from other films uproarious.[16] A review of the film on DVD Talk noted that it is "fascinating even if it's not entirely fun. There's definitely some interest in the classic wildlife footage, but the continued brutality of the hunters (which admittedly is not shown as explicitly as it could be) eventually becomes deadening. And the way the black characters are treated -- whether it's the actual African natives put down by the narration or the American actors put into demeaning situations -- is so offputting and infuriating that it would derail any self-respecting Bad Movie Night."[17]

Follow-ups[edit]

Congo Pictures followed Ingagi with an unsuccessful film titled Nu-Ma-Pu - Cannibalism in 1931, featuring much of the same crew. Like Ingagi, it purported to be a documentary, but was mostly fictitious.[9]

The 1937 film Love Life of a Gorilla likely borrows footage from Ingagi, as contemporary plot descriptions mention a character named "Colonel Hubert Winstead".[18]

The 1940 film Son of Ingagi, while not a sequel, is the first all-African-American horror film and features a house haunted by a female mad scientist and her missing link monster.

In 1947, Charlie Gemora announced his plans to direct and star in a jungle adventure movie that contemporary newspapers described as a sequel of Ingagi. However, the project never came to fruition.[6]

See also[edit]

- Congorilla, 1932 film

- Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives, a 2013 TV documentary that was exposed as a hoax.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Doherty 1999, pp. 236, 241.

- ^ a b c d e Erish, Andrew (January 8, 2006). "Illegitimate dad of 'Kong'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ Doherty 1999, pp. 238–40.

- ^ Gerald Perry, "Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong"

- ^ a b c "Federal Trade Commission Decisions Vol. 17 - vol17.pdf" (PDF).

- ^ a b Kelly Robinson audio commentary track. Ingagi (Blu-ray). Kino Lorber Home Video. January 5, 2021.

- ^ "Let's Drop In and Gossip With Old Cal York!". Photoplay. September 1930. pp. 102, 104 Note: "Cal York" was an amalgam of California and New York, and not a real name.

- ^ "Foreign "Ingagis"". Variety. July 30, 1930. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Bret Wood audio commentary track. Ingagi (Blu-ray). Kino Lorber Home Video. January 5, 2021.

- ^ "News From the Dailies". Variety. July 2, 1930. p. 60.

- ^ Ingagi 1930 Vitaphone Reel 1, Youtube. Accessed September 25, 2021

- ^ Charlie Gemora: Uncredited, full documentary at Youtube. Clips start at 17:39.Video accessed September 25, 2021 Archived September 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ingagi Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. November 2, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (March 17, 1931). "THE SCREEN; From Jail to Riches". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ "Ingagi". Internet Archive. Variety. April 16, 1930. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Atkinson 2021.

- ^ Remer, Justin. "Ingagi (Forbidden Fruit Vol. 8)". DVD Talk. DVDTalk.com. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Love Life of a Gorilla at the American Film Institute Catalog Retrieved July 3, 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Atkinson, Michael (May 2021). "Ingagi". Sight & Sound. Vol. 31, no. 4. p. 84.

- Berenstein, Rhona J. "White Heroines and Hearts of Darkness: Race, Gender and Disguise in 1930s Jungle Films", in Film History Vol. 6 No. 3 (Autumn 1994), Exploitation Films, pp. 314–339 (Published by Indiana University Press); Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3814926

- Doherty, Thomas Patrick (1999). Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11094-4.

External links[edit]

- Ingagi at IMDb

- Ingagi at AllMovie

- Connection of the film to King Kong

- Erish, Andrew (January 9, 2006). "Illegitimate dad of 'Kong'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2008. Alt URL

- Ingagi is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- 1930 films

- 1930 adventure films

- American black-and-white films

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s exploitation films

- Zoophilia in culture

- Films set in Belgian Congo

- History of racism in the cinema of the United States

- Hoaxes in the United States

- American adventure films

- Films about gorillas

- 1930s American films