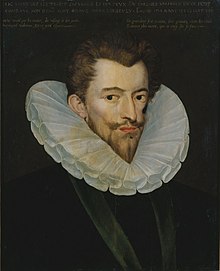

Jean d'O

Jean II d'O | |

|---|---|

| sieur de Manou sieur de Beauce | |

Coat of arms of the D'O family | |

| Born | 1552 |

| Died | 1596 |

| Noble family | Maison d'O |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte de Clermont |

| Issue | Louise d'O |

| Father | Jean I d'O |

| Mother | Hélène d'Illiers |

Jean II d'O, sieur de Manou and Beauce (1552–1596) was a French noble, courtier, royal favourite, soldier and captain of the guard during the latter French Wars of Religion. Brother to the more famous François d'O, Manou began his career during the reign of Charles IX, entering the service of the king's brother Anjou at the time of the siege of La Rochelle in 1573. He travelled with Anjou upon his election as king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and upon Anjou's return as Henri III of France he became first an échanson (cup-bearer) in 1574 then gentilhomme de la chambre by 1577 before finally being elevated to the prestigious post of captain of the guard in 1580. In 1575 he fought in the Fifth War of Religion and saw action under the overall command of the Duc de Guise at the Battle of Dormans.

In 1585 he became a chevalier (knight) of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit (Order of Saint-Esprit), the highest royal order of French chivalry. The following year he became a conseiller d'État (councillor of state). With the king at war with the Catholic Ligue (League) in 1589, Manou was with the king as he prepared to besiege Paris. He was therefore present for the assassination of the king on 1 August, and after some negotiations, remained loyal to the royalist cause by swearing loyalty to his Protestant successor Henri IV on condition of his conversion and the maintenance of his office. He died in 1596.

Early life and family[edit]

Jean II d'O was born in 1552 the son of Jean I d'O and Hélène d'Illiers.[1][2] The couple was married in 1534 and would have six children. Jean I d'O served as the captain of François I's guardes éccosais (Scots guard).[3] He was also the governor of Meulan and 'grand maréchal de Normandie' (grand marshal of Normandie).[2] He died around 1563.[4] Hélène d'Illiers was the dame de Manou.[2]

Jean II's elder sister, Françoise d'O (1550–) married the royal favourite of Henri III the sieur de Maintenon.[3] His elder brother, François d'O would become one of the king's closest favourites prior to his disgrace in 1581.[3] He had three younger brothers:[5]

- René d'O (–1586) sieur de Fresnes and gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (gentleman of the king's chamber) in 1580;[2]

- Louis d'O (–1583) sieur de La Ferrière, who died in service of the duc d'Alençon in Nederland[5]

- Charles d'O sieur de La Ferrière, abbot of Saint-Étienne de Caen and Saint-Julien de Tours then gentilhomme de la chambre du roi in 1594.[2]

Jean II d'O came from an ancient Norman noble family. The family had seen service at the battle of Azincourt in 1415 with a member of the house being killed on the field. The D'O served Charles VIII and Louis XII in the capacity of chamberlains.[3]

In the division of the family lands, Jean's elder brother François received the Norman and Perche seigneuries of O, Fresnes and Maillebois. Meanwhile, Jean inherited those territories that had been brought into the family by his mother Hélène, Manou and Beauce. The brothers would benefit at court from the memory of their father.[4]

Marriage and children[edit]

Jean II d'O married Charlotte de Clermont, dame de Tallard, a daughter of a gentleman in the ducal household of Anjou, Antoine III de Clermont-Tallard. This marriage was part of a strategy of building networks among the court families.[6]

They couple had the following issue:[2]

- Louise d'O, married in Gabriel du Quesnel, the marquis d'Allègre in 1599.[2]

After his arrival in Paris he initially resided with his brother in a hôtel on the rue Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre. In the 1580s Manou moved to a residence on the rue Saint-Honoré named 'l'Hermine'.[7]

Reign of Charles IX[edit]

Manou's royal service began around 1565.[4]

Anjou[edit]

From 1572 Manou would serve as a gentilhomme de la chambre (gentleman of the chamber) in the ducal household of the duc d'Anjou, brother to king Charles.[8]

He accompanied his lord for the attempted siege of La Rochelle in 1573, the city having gone into rebellion after the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.[9][10] After several months of inconclusive struggle the siege was brought to a conclusion by the news that Anjou had been elected as king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a peace was therefore arranged between the crown and the Protestants.[11]

When the duc d'Anjou was elected as king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1573, both Manou and his elder brother D'O accompanied the prince to his new kingdom.[12] During his time in the Commonwealth, René de Villequier acted as a mentor to the young Manou.[6] Not all Henri's companions would remain with him for the length of his reign on the Commonwealth, and among those who returned to France was Manou's brother D'O. Given there is no record of Manou having returned as part of Henri's departure from the kingdom, Le Roux speculates that Manou may have left early with D'O.[13]

Reign of Henri III[edit]

Échanson[edit]

Upon Anjou's return to France to assume the crown as Henri III, those of his household who were too young to hold any other position were made échansons (cup-bearers). This was the case with Manou, the seigneur de Bussy d'Amboise, the comte de Caylus and the seigneur de Dinteville.[14] His elder brother D'O meanwhile spectacularly rose in the kings favour at a speed only equalled (in this period) by Saint-Luc.[4]

Fifth war of religion[edit]

During the royal campaign of the Fifth War of Religion, many of the king's favourites fought with the duc de Guise's army for his victorious Dormans campaign.[15] They were brought into the campaign by the poverty of the crown which lacked the funds to raise many other troops and only served briefly. Saint-Sulpice was the first to arrive in Guise's camp at Langres on 16 September. The collective of favourites (who would serve in a company of 350 lances under the overall authority of the sieur de Fervaques) included Caylus, Saint-Luc, Saint-Sulpice, Manou and D'O.} Manou and the other favourites demonstrated themselves ardent in battle.[16] On 10 October Guise's force including the royal favourites bested the vanguard of the Protestant army at Dormans.[17]

Having served the king since 1574 as his échanson he became a gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (gentleman of the kings' chamber) from March 1577 at the latest.[18] This office brought with it a wage of 600 livres.[14]

Captain of the guard[edit]

In March 1580 Manou received a further promotion in terms of royal office when he replaced the seigneur de Rambouillet as a captain of the royal guard around March 1580.[19] The dispossession of Rambouillet from such a prestigious office required extensive compensation, and he was granted the promise of a gift of 20,000 livres, a pension of a further 4,000 livres and the government of Metz.[20]

Manou would serve as one of the captains of Henri's bodyguard, alongside Joachim de Châteauvieux and Charles de Balsac, seigneur de Clermont d'Entragues.[21]

A few months into his new role as the captain of the guard, Saint-Luc was disgraced for obscure reasons, and the favourite fled from court to the security of his governate of Brouage. His wife Jeanne de Cossé was arrested on 7 February. By July her house arrest was the responsibility of Manou's guard company.[22] She wrote to her uncle Marshal Cossé who protested to the king about her treatment.[23]

Henri was very sensitive to his favourites having relations with his brother the duc d'Alençon who in 1581 was undertaking an enterprise in Spanish Nederland. Both Manou and his younger brother Fresnes were involved in supporting the prince in these endeavours, in response Henri got more severe about the subject. Around this time, their elder brother D'O was disgraced by the king.[24]

Saint-Esprit[edit]

In 1585 he was made a chevalier of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit (Order of Saint-Esprit) the highest royal order of chivalry. This was followed by his establishment as a conseiller d'État (councillor of state) in 1586.[2]

War with the ligue[edit]

In 1588 Henri resolved of the necessity to be rid of the leader of the Catholic Ligue (League), and had the duc de Guise assassinated in December.[25][26] This brought him into a state of war with the ligue and much of his kingdom rebelled.[27] He therefore aligned himself with the Protestant king of Navarre and made plans to recapture the ligueur (leaguer) held city of Paris.[28][29]

The combined royal Protestant army under the command of Henri III and the king of Navarre approached Paris with the intention of putting the ligueur held city under siege. Henri established himself at the hôtel d'Aulnay in Saint-Cloud for the conduct of the coming battle on 30 July. He was surrounded at this time by his grand prévot Richelieu, his prémier valet de chambre Pierre du Halde and his new favourites the baron de Termes and the sieur de Mirepoix. To protect him, the captains of his guards, the seigneur de Clermont d'Entragues, Larchant and Manou.[30][31]

Their protection would be important at this time, as the ligue had already tried and failed in assassination attempts against Henri in the proceeding months.[32] On 1 August a Jacobin friar named Jacques Clément requested an audience with the king, he claimed to have information from the royalits Parisian Parlementaire de Harlay that the king's allies in the city were preparing to open the gates for him. Clément asked to speak privately with the king, who responded by ordering the baron de Termes and another notable to leave their company. Once alone Clément plunged a knife into Henri's abdomen, various guards then burst into the room among them Mirepoix and cut Clément down.[33]

Reign of Henri IV[edit]

Loyalist[edit]

As Henri faded from life, he had all his servants, including Manou swear to serve Navarre if he died.[34] The wound was ultimately not recoverable and on 2 August, Henri died. Agrippa d'Aubigné described the scene that followed. D'O, Manou, Châteauvieux, Clermont d'Entragues and Dampierre were gathered in the room. They all became distraught throwing their hats to the ground, clenching their fists and praying that they would rather die a thousand deaths than serve Navarre.[34] At Henri's insistence, Salic Law was to be respected, meaning the Protestant king of Navarre would succeed him as Henri IV.[35] Henri was not insensitive to the scene which he saw, he understood none of these men wished to abide by the oaths they had taken to the prior king the night previously, not only did serving a Protestant violate their religion, but also their self interest. Henri already had many servants, and would have little need of many of their services. Beyond these more immediate material causes of grief they had taken on a great responsibility with the oath they made to the late king.[34]

On 3 August, the day after Henri's death, Manou and all the other close companions of the king who had been with him in his final moments put their signature to a document describing Henri's final moments. The document framed Henri's death as that of a model Christian. It was intended to go first to the bishop of Paris Pierre de Gondi, and then be dispatched to Roma so that it would be clear to the Pope that Henri had died an irreproachable Catholic.[21]

Henri recognised the necessity of reassuring the Catholic lords who had made such a display at the deathbed of their late king. To this end on 4 August he declared that he would protect the Catholic church, and that within the next six months he would convene a council that could instruct him in this religion. Those who had served Henri would be maintained in their positions (thus Manou became a captain of the guard for Henri IV)[36] and would jointly pursue justice for the regicide. Many Catholic grandees decided to back Henri under these terms and signed the 'Saint-Cloud declaration' as it became known, with some believing Henri's conversion to Catholicism would come in a matter of weeks (as opposed to the several years it actually took).[37]

Among the signatories to the declaration were the prince de Conti, duc de Longueville, duc de Piney, Marshal de Biron, Marshal d'Aumont, Rohan, the lieutenant-general of Champagne Dinteville, the former governor of Metz Rambouillet, Richelieu and the captains of the guard, Châteauvieux, Clermont d'Entragues and Manou.[37] A couple of the notables would have supported Henri even without his promise of eventual conversion, however that part of the agreement was important for Manou.[38]

Death[edit]

Having been in the service of Henri IV for seven years, Manou died in 1596.[2]

Sources[edit]

- Babelon, Jean-Pierre (2009). Henri IV. Fayard.

- Carroll, Stuart (2011). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Chevallier, Pierre (1985). Henri III: Roi Shakespearien. Fayard.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Bouquins.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Pitts, Vincent (2012). Henri IV of France: His Reign and Age. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the French Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2000). La Faveur du Roi: Mignons et Courtisans au Temps des Derniers Valois. Champ Vallon.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2006). Un Régicide au nom de Dieu: L'Assassinat d'Henri III. Gallimard.

- Sutherland, Nicola (1980). The Huguenot Struggle for Recognition. Yale University Press.

References[edit]

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Le Roux 2000, p. 744.

- ^ a b c d Jouanna 1998, p. 1162.

- ^ a b c d Le Roux 2000, p. 226.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 227.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 242.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 291.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 145.

- ^ Knecht 2016, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 221.

- ^ Knecht 2016, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 426.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 156.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2000, p. 222.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 420.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 421.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 316.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 190.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 191.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 442.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 443.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 434.

- ^ Carroll 2011, p. 289.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 266.

- ^ Roberts 1996, p. 174.

- ^ Sutherland 1980, p. 262.

- ^ Pitts 2012, p. 142.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 295.

- ^ Le Roux 2006, p. 272.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 298.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 301.

- ^ a b c Babelon 2009, p. 453.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 306.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 706.

- ^ a b Le Roux 2006, p. 292.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 705.