Languages of Lebanon

| Languages of Lebanon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) |

| Semi-official | French |

| Main | Lebanese dialect of Levantine Arabic |

| Minority | Western Armenian |

| Foreign | English |

| Signed | Levantine Sign Language |

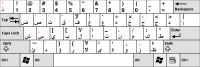

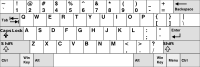

| Keyboard layout | |

In Lebanon, most people communicate in the Lebanese variety of Levantine Arabic, but Lebanon's official language is Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). French is recognized and used next to MSA on road signs and Lebanese banknotes. Lebanon's native sign language is the Lebanese dialect of Levantine Arabic Sign Language. English is the fourth language by number of users, after Levantine, MSA, and French. Most Armenians in Lebanon can speak Western Armenian, and some can speak Turkish.

Lebanon exists in a state of diglossia: MSA is used in formal writing and the news, while Lebanese Arabic—the variety of Levantine Arabic—is used as the native language in conversations and for informal written communication. When writing Levantine, Lebanese people use the Arabic script (more formal) or Arabizi (less formal). Arabizi can be written on a QWERTY keyboard and is used out of convenience.

Mutual intelligibility between Lebanese and other Levantine varieties is high, while MSA and Levantine are mutually unintelligible. Despite that, Arabs consider both varieties of Arabic to be a part of a single Arabic language. Some sources count Levantine and MSA as two languages of the same language family.

Statistics[edit]

According to Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024),[1] these languages have the most users in Lebanon:

- Levantine Arabic – 5,230,000

- Modern Standard Arabic – 4,780,000

- French – 2,530,000

- English – 2,130,000

- Western Armenian – 261,000

- Turkish – 189,000

Diglossia and local varieties' classification[edit]

Lebanon—and the Arab world in general—exists in a state of diglossia:[2] the language used in literature, formal writing, or other specific settings is very divergent from that used in conversations. Lebanon's official language, Modern Standard Arabic (MSA),[3] has no native speakers in or outside Lebanon.[4] It is almost never used in conversations[5] and is learned through formal instruction rather than transmission from parent to child.[6] MSA is the language of literature, official documents, and formal written media (newspapers, instruction leaflets, school books),[6] and in spoken form, it is mostly used when reading from a scripted text (e.g., news bulletins) and for prayer and sermons in the mosque or church.[6] Levantine, conversely, is spoken natively and used in conversations, TV shows, films, and advertisements.[7] This diglossia has been compared to the use of Latin as the sole written, official, liturgical, and literary language in Europe during the medieval period, while Romance languages were the spoken languages.[8][9] Levantine—specifically its Palestinian dialect—is the closest Arabic variety to MSA,[10][11][12] but Levantine and MSA are not mutually intelligible.[13][2] They differ significantly in their phonology, morphology, lexicon and syntax,[14] and exposure to MSA in the early childhood of native speakers of an Arabic variety results in a linguistic system that behaves like that of bilinguals.[15]

Levantine speakers often call their language العامية al-ʿāmmiyya, 'slang', 'dialect', or 'colloquial' (lit. 'the language of common people'), to contrast it to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Classical Arabic (الفصحى al-fuṣḥā, lit. 'the eloquent').[a][17][18][19] They also call their spoken language عربي ʿarabiyy, 'Arabic'.[20] Alternatively, they identify their language by the name of their country, such as لبناني libnāni, 'Lebanese'.[21] شامي šāmi can refer to Damascus Arabic, Syrian Arabic, or Levantine as a whole.[22] Lebanese literary figure Said Akl led a movement to recognize the "Lebanese language" as a prestigious language instead of MSA.[23] Most people consider Arabic to be a single language.[24] The ISO 639-3 standard, however, classifies Arabic as a macrolanguage and Levantine as one of its languages, giving it the language code "apc".[25]

Code-switching and loanwords[edit]

Code-switching (alternating between languages in a single conversation) between Levantine, MSA, French, and English is very common in Lebanon, often being done in both casual situations and formal situations like TV interviews.[26][27] This prevalence of code-switching has led to phrases that naturally embed multiple linguistic codes being used in daily sentence, like the typical greeting "hi, كيفك؟[b] Ça va ?", which combines English, Levantine and French.[28][29][30] Code-switching also happens in politics. For instance, not all politicians master MSA, so they rely on the Lebanese Levantine Arabic.[31]

Additionally, many words used in the Lebanese dialect of Levantine have been borrowed from French, such as telfizyōn ⓘ(French: télévision ⓘ, meaning 'television'), balkōn ⓘ(French: balcon ⓘ, meaning 'balcony') and doktōr ⓘ (French: docteur ⓘ, meaning 'doctor'),[32] and from English, such as CD, crispy, hot dog, and keyboard,[33] with some phrases and verbs being altered to follow the syntax of Levantine Arabic, instead of English. For example, shayyik comes from the English word 'check', and sayyiv comes from the English word 'save'.[33]

Minority languages[edit]

Western Armenian is used between the Armenians in Lebanon,[34][35] who fled to Lebanon between 1895 and 1939 for multiple reasons, most notably the Armenian genocide.[c][37] In 2015, Armenians made up around 4% of Lebanon's population.[38] Their mother tongue remains widespread,[34] and some Armenians in Lebanon can also speak Turkish, more than a century after their ancestors left Turkey.[24]

Some Kurds fled to Lebanon from violence and poverty in Turkey, but they are now dispersed in Lebanon and have largely abandoned Kurdish languages.[d][34] Kurds in Lebanon were estimated at 70,000 in 2020, and Kurmanji's users at 23,000.[1]

Syriac Aramaic is also spoken as a first language in some Lebanese communities such as Syriac Catholics, Syriac Orthodox and Assyrian Lebanese.[citation needed] It is also used in liturgies in other communities such as Maronite Catholics.[citation needed]

Usage[edit]

Conversation[edit]

Lebanon's native language, Levantine Arabic,[1] is the main language used in conversations. MSA, despite being Lebanon's second language by number of users,[1] is almost never used in conversations,[5] while English[33] and French[40] are, even between some native speakers of Levantine. Levantine Arabic Sign Language is Lebanon's native sign language, and Lebanon's deaf population is estimated at 12,000.[41][1]

Oral media[edit]

Many public and formal speeches and most political talk shows are in Lebanese, not MSA.[31] In the Arab world, most films and songs are in vernacular Arabic.[42] Egypt was the most influential center of Arab media productions (movies, drama, TV series) during the 20th century,[43] but Levantine is now competing with Egyptian.[44] As of 2013, about 40% of all music production in the Arab world was in Lebanese.[43] Lebanese television is the oldest and largest private Arab broadcast industry.[45] Most big-budget pan-Arab entertainment shows are filmed in the Lebanese dialect in the studios of Beirut. Moreover, the Syrian dialect dominates in Syrian TV series (such as Bab al-Hara) and in the dubbing of Turkish television dramas, which are both aired in Lebanon.[43][46] With the release of Secret of the Wings in 2012, Disney began re-dubbing and dubbing its films in MSA, instead of Egyptian,[47][48] and in March 2013, Disney and pan-Arab television network Al Jazeera made a deal allowing the latter to distribute some of Disney's MSA-dubbed shows and films.[47][49] The release of Frozen with an MSA dub and without an Egyptian one caused a controversy in the Arab world.[47][7]

Lebanese zajal and other forms of oral poetry are often in Levantine.[50][26]

Typically, news bulletins are in MSA.[2] On the popular television network LBCI, Arab and international news bulletins are in MSA, while the Lebanese national news broadcast is in a mix of MSA and Lebanese Arabic.[2] Lebanese TV station OTV and some radio stations that cover news of the Armenian diaspora in Lebanon broadcast daily news bulletins in Armenian.[34]

Lebanon used to have two francophone television stations, but they were shut down in the mid-1990s. Show hosts on television networks that are traditionally affiliated with Christians, such as MTV and LBCI, tend to use more English and French words than hosts in networks owned by Muslims, such as Future TV, Al-Manar, and NBN.[33]

Writing and scripts[edit]

Unlike Levantine,[51] Modern Standard Arabic has a standardized spelling in the Arabic script[52] and is typically used in literature, official documents, newspapers, school books, and instruction leaflets.[6] In formal media, Levantine is seldom written, except for some novels, plays, and humorous writings.[53][54] Subtitles are usually in MSA,[55] sometimes translating Arabic dialects to MSA.[56]

Most Arabs struggle to write MSA correctly.[24] On social media[51] and when texting, they use their native variety, either in the Arabic script or Arabizi. Arabizi combines the Latin alphabet with Western Arabic numerals to make up for sounds unavailable with the Latin alphabet alone.[57][30] The numbers are visually similar to the Arabic character they represent. For example, 3 represents "ع".[58] Arabizi is commonly used on social media and discussion forums, SMS messaging, and online chat,[59] especially among younger generations. Arabizi initially evolved because of the lack of support for Arabic letters, but it is now used to save time switching keyboards and, for typists who are not proficient in an Arabic keyboard, save time typing.[60] A 2012 study found that, when writing in Levantine on Facebook, Arabizi is more common than the Arabic script in Lebanon, while the Arabic script is more common in Syria.[61] Several studies have reported that the complexity of Arabic orthography slows down the word identification process,[7] but Arabizi is not always read faster than the Arabic script, depending on vowelization, the reader's gender, and other factors.[7]

In the 1960s, Lebanese poet Said Akl—inspired by the Maltese and Turkish alphabets—[62] designed a new Latin alphabet for Lebanese and promoted the official use of Lebanese instead of MSA,[63] but this movement was unsuccessful.[64][65]

Education[edit]

Between 1994 and 1997, the Council of Ministers passed a new National Language Curriculum that required schools to use either English or French in natural sciences and mathematics.[33][66] In general, school students are exposed to two or three languages: MSA and either French, English or both.[27] Students' native language, Levantine, is not taught in schools, although MSA-medium lessons are often taught in a mix of MSA and Levantine with, for instance, the lesson read out in MSA and explained in Levantine.[26][3] Foreign language teachers, such as English and French teachers, also commonly code-switch to Levantine.[40]

Although all language teachers face difficulties, especially in low socio-economic schools, MSA teachers' teaching resources are inferior to those of English and French, focusing mostly on classical books, as other resources are rare.[40] Many young Lebanese struggle with basic MSA reading and writing skills,[5] while Syrian refugees in Lebanon transitioning from the MSA-centric Syrian education system to the English- and French-centric Lebanese system struggle with English and French. They are therefore often placed several grade levels below their age level, causing negative consequences on their psychosocial well-being.[67]

The number of students learning in English is increasing, while those learning in French is decreasing: In 2019, 50% of school students studied in French, compared to 70% twenty years prior to that, and 55% of French-educated students chose to go to English-medium universities.[68][69] Lebanon's brain drain is high,[47][70] and its job market is weak.[47][40] Foreign language proficiency, therefore, is highly beneficial to Lebanese graduates, as it helps them find jobs abroad.[40]

Government and law[edit]

Following its independence in 1943, Lebanon's official language changed from French and MSA to just MSA. Today, MSA is the official language, while French is a recognized one.[51][1] Lebanon's national anthem[71] and all government-related announcements, documents, and publications are in MSA.[33] French is also used, alongside MSA, on road signs, the Lebanese lira and public buildings.

-

The Lebanese lira is in Modern Standard Arabic on one side and French on the other

-

French-language inscription "Banque du Liban" on the headquarters of the Bank of Lebanon

Lebanese Arabic—the variety of Levantine Arabic—is used in courtrooms, but in order to record court proceedings, the judge restates in MSA what the suspect has said, and the court recorder handwrites the judge's translation.[33][72] This process, according to a report funded and led by the World Bank, "risks an edit or an omission in the restatement by the judge."[73][74]

Brands and businesses[edit]

Email communication and announcements in professional job settings are mostly through English.[33] Of Lebanon's 34 radio stations, 11 have either French or English names.[33] Using photographs from 2015, a 2018 study of the linguistic landscape of Lebanon's capital, Beirut, found that the Arabic script is only used in 20% of storefront's primary text (store's name) and 9% of secondary text (other information, such as opening hours). The Armenian script was absent.[75]

History[edit]

Starting in the 1st millennium BCE, Aramaic was the dominant spoken language and the language of writing and administration in the Levant—[76] where Lebanon is. Because there are no written sources, the history of Levantine Arabic before the modern period is unknown.[77] In the early 1st century CE, a great variety of Arabic dialects were already spoken by various nomadic or semi-nomadic Arabic tribes in the Levant.[78][79][26] These dialects were local, coming from the Hauran—and not from the Arabian Peninsula—[80] and related to later Classical Arabic.[81] Initially restricted to the steppe, Arabic-speaking nomads started to settle in cities and fertile areas after the Plague of Justinian in 542 CE.[80] These Arab communities stretched from the southern extremities of the Syrian Desert to central Syria, the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and the Beqaa Valley.[82][83] The Muslim conquest of the Levant (634–640[84][85]) brought Arabic speakers from the Arabian Peninsula who settled in the Levant.[86] Arabic became the language of trade and public life in cities, while Aramaic continued to be spoken at home and in the countryside.[83] The language shift from Aramaic to vernacular Arabic was a long process over several generations, with an extended period of bilingualism, especially among non-Muslims.[83][87] Christians continued to speak Syriac for about two centuries, and Syriac remained their literary language until the 14th century.[88][89] In its spoken form, Aramaic nearly disappeared, except for a few Aramaic-speaking villages,[89] but it has left substrate influences on Levantine.[87] The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century reduced the use of Turkish words due to Arabization and the negative perception of the Ottoman era among Arabs.[90] With the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (1920–1946),[91] the British protectorate over Jordan (1921–1946), and the British Mandate for Palestine (3–1948), French and English words gradually entered Levantine Arabic.[92][93]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Native speakers of Arabic generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Classical Arabic and refer to both as العربية الفصحى al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā, lit. 'the eloquent Arabic'.[16]

- ^ Transliterated as kīfak (when asked to a male) or kīfik (when asked to a female)

- ^ According to Minority Rights Group,[36] Cilician Catholics seeking refuge from the Armenian Orthodox Church's persecution initially came to Lebanon in the 18th century. Subsequent and bigger immigration waves arrived due to massacres by the Turks in 1895–1896 and the Armenian genocide of 1915. More arrived when France's attempt to establish an Armenian entity in Cilicia failed in 1920–1921. The last influx resulted from France ceding Alexandretta to Turkey in 1939.

- ^ Kurdish is often seen as a single language, and its descendants Kurmanji and Zazaki as it dialects, instead of separate languages.[39]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Lebanon, in Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2024). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (27th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ a b c d Qwaider, Chatrine; Abu Kwaik, Kathrein (2022). Resources and Applications for Dialectal Arabic: the Case of Levantine. University of Gothenburg. pp. 136, 139. ISBN 978-91-8009-803-8.

- ^ a b Al-Wer 2006, p. 1917.

- ^ Arabic, Standard, 24th Edition, Ethnologue

- ^ a b c "Campaign to save the Arabic language in Lebanon". BBC News. 16 June 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d Al-Wer & Jong 2017, p. 525.

- ^ a b c d Muhanna, Elias (30 May 2014). "Translating "Frozen" Into Arabic". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Versteegh 2014, p. 241.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz Dominik (2017). "The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity?". Journal of Nationalism, Memory and Language Politics. 11 (2). De Gruyter: 117. doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006. hdl:10023/12443. ISSN 2570-5857.

- ^ Harrat S., Meftouh K., Abbas M., Jamoussi S., Saad M., Smaili K., (2015), Cross-Dialectal Arabic Processing. In: Gelbukh A. (eds), Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing. CICLing 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9041. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18111-0_47, PDF.

- ^ Conference Proceedings, Arabic Dialect Identification in the Context of Bivalency and Code-Switching, El-Haj, Mahmoud, Rayson, Paul, Aboelezz, Mariam, Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), 2018, European Language Resources Association (ELRA), Miyazaki, Japan, el-haj-etal-2018-arabic, https://aclanthology.org/L18-1573

- ^ Kathrein Abu Kwaik, Motaz Saad, Stergios Chatzikyriakidis, Simon Dobnika, A Lexical Distance Study of Arabic Dialects, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 142, 2018, Pages 2–13, ISSN 1877-0509, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.456

- ^ al-Sharkawi, Muhammad (2016). History and Development of the Arabic Language. Taylor & Francis. p. xvi. ISBN 978-1-317-58863-4. OCLC 965157532.

- ^ Cowell 1964, pp. vii–x.

- ^ Eviatar, Zohar; Ibrahim, Raphiq (1 December 2000). "Bilingual Is as Bilingual Does: Metalinguistic Abilities of Arabic-Speaking Children". Applied Psycholinguistics. 21 (4): 451–471. doi:10.1017/S0142716400004021. ISSN 0142-7164. S2CID 145218828.

- ^ Badawi, El-Said M. (1996). Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said Badawi. American University in Cairo Press. p. 105. ISBN 977-424-372-2. OCLC 35163083.

- ^ Shendy, Riham (2019). "The Limitations of Reading to Young Children in Literary Arabic: The Unspoken Struggle with Arabic Diglossia". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 9 (2). Academy Publication: 123. doi:10.17507/tpls.0902.01. S2CID 150474487.

- ^ Eisele, John C. (2011). "Slang". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_eall_com_0310.

- ^ Liddicoat, Lennane & Abdul Rahim 2018, p. I.

- ^ al-Sharkawi, Muhammad (2010). The Ecology of Arabic – A Study of Arabicization. Brill. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-04-19174-7. OCLC 741613187.

- ^ Shachmon & Mack 2019, p. 362.

- ^ Shoup, John Austin (2008). Culture and Customs of Syria. Greenwood Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-313-34456-5. OCLC 183179547.

- ^ Płonka 2006, p. 433.

- ^ a b c "A language with too many armies and navies?". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "apc | ISO 639-3". iso639-3.sil.org. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Behnstedt, Peter (2011). "Syria". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0330.

- ^ a b Bahous, Rima N.; Nabhani, Mona Baroud; Bacha, Nahla Nola (2 October 2014). "Code-switching in higher education in a multilingual environment: a Lebanese exploratory study". Language Awareness. 23 (4): 353–368. doi:10.1080/09658416.2013.828735. ISSN 0965-8416. S2CID 144596902.

- ^ Bizri, Fida (November 2013). "Linguistic Green Lines in Lebanon". Mediterranean Politics. 18 (3): 444–459. doi:10.1080/13629395.2013.834568. ISSN 1362-9395. S2CID 143346947.

- ^ "In polyglot Lebanon, some fear Arabic language is losing ground". Associated Press. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ a b "In polyglot Lebanon, one language falls behind: Arabic". The Independent. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ a b Wardini, Elie (2011). "Lebanon". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_SIM_001001.

- ^ Sakr, Georges (2018). A Discussion of Issues from French Loans in Lebanese (PDF) (MSc Linguistics thesis). University of Edinburgh.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Esseili, Fatima (2017). "A sociolinguistic profile of English in Lebanon". World Englishes. 36 (4): 684–704. doi:10.1111/weng.12262. ISSN 1467-971X. S2CID 148739564.

- ^ a b c d Kadi, Samar (18 March 2016). "Armenians, Kurds in Lebanon hold on to their languages". The Arab Weekly.

- ^ Erchoff, Sami (5 October 2021). "As Lebanon collapses, its Armenian community disappears". The New Arab. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Lebanon – World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Lebanon". diaspora.gov.am. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Lebanon – World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Ozek, Fatih; Saglam, Bilgit; Gooskens, Charlotte (13 November 2021). "Mutual intelligibility of a Kurmanji and a Zazaki dialect spoken in the province of Elazığ, Turkey". Applied Linguistics Review. 14 (5): 1411–1449. doi:10.1515/applirev-2020-0151.

- ^ a b c d e Bahous, Rima; Bacha, Nahla Nola; Nabhani, Mona (9 December 2011). "Multilingual educational trends and practices in Lebanon: A case study". International Review of Education. 57 (5–6): 5. Bibcode:2011IREdu..57..737B. doi:10.1007/s11159-011-9250-8. ISSN 0020-8566.

- ^ Hendriks, Bernadet (2008). "Jordanian Sign Language: Aspects of grammar from a cross-linguistic perspective" (PDF). LOT. ISBN 978-90-78328-67-4.

- ^ Shendy, Riham (2019). "The Limitations of Reading to Young Children in Literary Arabic: The Unspoken Struggle with Arabic Diglossia". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 9 (2). Academy Publication: 123. doi:10.17507/tpls.0902.01. S2CID 150474487.

- ^ a b c Hachimi, Atiqa (2013). "The Maghreb-Mashreq language ideology and the politics of identity in a globalized Arab world". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 17 (3). Wiley: 275. doi:10.1111/josl.12037.

- ^ Uthman, Ahmad (2 August 2017). "Ahmad Maher: Damascus Arabic is a real threat to Egyptian drama". Erem News (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Khazaal, Natalie (2021). "Lebanese broadcasting: Small country, influential media". In Miladi, Noureddine; Mellor, Noha (eds.). Routledge Handbook on Arab Media. Taylor & Francis. p. 175. doi:10.4324/9780429427084. hdl:10576/26105. ISBN 978-0-429-76290-1. OCLC 1164821650. S2CID 225023449. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Jabbour, Jana (2015). "An illusionary power of seduction?". European Journal of Turkish Studies (21). Association pour la Recherche sur le Moyen-Orient. doi:10.4000/ejts.5234. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Di Giovanni, Elena (18 February 2016). "Dubbing and Redubbing Animation: Disney in the Arab World". Altre Modernità: 92–106 Pages. doi:10.13130/2035-7680/6850.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (11 March 2013). "Disney Content to Air on Al Jazeera Kids' Channel". Variety. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Disney to dub new film Encanto in Egyptian Arabic after 10-year hiatus – Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Kazarian, Shahe S. (2011). "Humor in the collectivist Arab Middle East: The case of Lebanon". Humor. 24 (3). De Gruyter: 340. doi:10.1515/humr.2011.020. S2CID 44537443.

- ^ a b c Abu Kwaik, Kathrein; Saad, Motaz; Chatzikyriakidis, Stergios; Dobnik, Simon (May 2018). "Shami: A Corpus of Levantine Arabic Dialects". Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018). Miyazaki, Japan: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

- ^ Al-Kahtany, Abdallah Hady (1997). "The 'Problem' of Diglossia in the Arab World: An Attitudinal Study of Modern Standard Arabic and the Arabic Dialects". Al-'Arabiyya. 30: 1–30. ISSN 0889-8731. JSTOR 43192773.

- ^ Mejdell, Gunvor (2017). "Changing Norms, Concepts and Practices of Written Arabic: A 'Long Distance' Perspective". In Høigilt, Jacob; Mejdell, Gunvor (eds.). The Politics of Written Language in the Arab World: Writing Change. Brill. p. 81. doi:10.1163/9789004346178_005. ISBN 978-90-04-34617-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76vkk. OCLC 992798713.

- ^ Davies, Humphrey T. (2011). "Dialect Literature". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0086.

- ^ Abu-Rayyash, Hussein; Haider, Ahmad S.; Al-Adwan, Amer (30 January 2023). "Strategies of translating swear words into Arabic: a case study of a parallel corpus of Netflix English-Arabic movie subtitles". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 10 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01506-3. ISSN 2662-9992. S2CID 256362270.

- ^ Al-Abbas, Linda S.; Haider, Ahmad S. (1 January 2021). Sanchez Ramos, Maria del Mar and (ed.). "Using Modern Standard Arabic in subtitling Egyptian comedy movies for the deaf/ hard of hearing". Cogent Arts & Humanities. 8 (1). doi:10.1080/23311983.2021.1993597. ISSN 2331-1983. S2CID 240142296.

- ^ Laughlin, Alex Sujong (10 October 2022). "The Imperfect Art of Romanization". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Haghegh, Mariam (15 May 2021). "Arabizi across Three Different Generations of Arab Users Living Abroad: A Case Study". Arab World English Journal for Translation and Literary Studies. 5 (2): 156–173. doi:10.24093/awejtls/vol5no2.12.

- ^ Bies, Ann; Song, Zhiyi; Maamouri, Mohamed; Grimes, Stephen; Lee, Haejoong; Wright, Jonathan; Strassel, Stephanie; Habash, Nizar; Eskander, Ramy; Rambow, Owen (2014). "Transliteration of Arabizi into Arabic Orthography: Developing a Parallel Annotated Arabizi-Arabic Script SMS/Chat Corpus". Proceedings of the EMNLP 2014 Workshop on Arabic Natural Language Processing (ANLP). EMNLP. Doha: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 93. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.676.4146. doi:10.3115/v1/w14-3612.

- ^ Haghegh, Mariam (15 May 2021). "Arabizi across Three Different Generations of Arab Users Living Abroad: A Case Study". Arab World English Journal for Translation and Literary Studies. 5 (2): 156–173. doi:10.24093/awejtls/vol5no2.12.

- ^ Abu Elhija, Dua'a (2014). "A new writing system? Developing orthographies for writing Arabic dialects in electronic media". Writing Systems Research. 6 (2). Informa: 193, 208. doi:10.1080/17586801.2013.868334. S2CID 219568845.

- ^ Płonka 2006, pp. 425–426, 457.

- ^ Płonka 2006, pp. 425–426, 430.

- ^ Płonka 2006, pp. 423, 463–464.

- ^ Abu Elhija 2019, pp. 23–24.

- ^ "Lebanon – Educational System—overview". education.stateuniversity.com. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Garbern, Stephanie Chow; Helal, Shaimaa; Michael, Saja; Turgeon, Nikkole J.; Bartels, Susan (25 April 2020). "'It will be a weapon in my hand': The Protective Potential of Education for Adolescent Syrian Refugee Girls in Lebanon". Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees. 36 (1): 3–13. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.40609. ISSN 1920-7336. S2CID 219649139.

- ^ "In Lebanon, English overtakes French in universities". L'Orient Today. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "English Is The New French: The Case Of Lebanon". The Friday Times. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Worth, Robert F. (24 December 2007). "Home on Holiday, the Lebanese Say, What Turmoil?". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "National anthem – The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ "Lebanon: Legal and Judicial Sector Assessment" (PDF). World Bank: 25. 2003.

- ^ Khachan, Victor (August 2010). "Arabic–Arabic Courtroom Translation in Lebanon". Social & Legal Studies – SOC LEGAL STUD. 19 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1177/0964663909351437. S2CID 143827696.

- ^ "Lebanon: Legal and Judicial Sector Assessment" (PDF). World Bank: 25. 2003.

- ^ Karam, Fares J.; Warren, Amber; Kibler, Amanda K.; Shweiry, Zinnia (2 April 2020). "Beiruti linguistic landscape: an analysis of private store fronts". International Journal of Multilingualism. 17 (2): 196–214. doi:10.1080/14790718.2018.1529178. ISSN 1479-0718.

- ^ Versteegh 2014, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Lentin 2018, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Lentin 2018, p. 171.

- ^ Magidow 2013, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Magidow 2013, p. 186.

- ^ Versteegh 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Retsö, Jan (2011). "ʿArab". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_eall_com_0020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Retsö, Jan (2011). "Aramaic/Syriac Loanwords". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_eall_com_0024. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Khalidi, Walid Ahmed. "Palestine – Roman Palestine". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Ochsenwald, William L. "Syria – Hellenistic and Roman periods". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Al-Wer & Jong 2017, pp. 530–531.

- ^ a b Neishtadt, Mila (2015). "The Lexical Component in the Aramaic Substrate of Palestinian Arabic". In Butts, Aaron (ed.). Semitic Languages in Contact. Brill. p. 281. doi:10.1163/9789004300156_016. ISBN 978-90-04-30015-6. OCLC 1105497638.

- ^ Versteegh 2014, p. 127.

- ^ a b Erdman, Michael (2017). "From Language to Patois and Back Again: Syriac Influences on Arabic in Mont Liban during the 16th to 19th Centuries". Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal Journal. 55 (1). Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and All the East: 3. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Brustad & Zuniga 2019, p. 425.

- ^ Aslanov, Cyril (2018). "The Historical Formation of a Macro-ecology: the Case of the Levant". In Mühlhäusler, Peter; Ludwig, Ralph; Pagel, Steve (eds.). Linguistic Ecology and Language Contact. Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132, 134, 145. doi:10.1017/9781139649568.006. ISBN 978-1-107-04135-6. OCLC 1302490060. S2CID 150123855. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Al-Wer 2006, pp. 1920–1921.

- ^ Guba, Abu (August 2016). Phonological Adaptation of English Loanwords in Ammani Arabic (PhD thesis). University of Salford. p. 7. OCLC 1063569424. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Al-Wer, Enam (2006). "The Arabic-speaking Middle East". In Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J; Trudgill, Peter (eds.). Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Vol. 3. De Gruyter. pp. 1917–1924. doi:10.1515/9783110184181.3.9.1917. ISBN 978-3-11-019987-1. OCLC 1089428643.

- Al-Wer, Enam; Jong, Rudolf (2017). "Dialects of Arabic". In Boberg, Charles; Nerbonne, John; Watt, Dominic (eds.). The Handbook of Dialectology. Wiley. pp. 523–534. doi:10.1002/9781118827628.ch32. ISBN 978-1-118-82755-0. OCLC 989950951.

- Lentin, Jérôme (2018). "The Levant". In Holes, Clive (ed.). Arabic Historical Dialectology: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Approaches. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–205. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198701378.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-870137-8. OCLC 1059441655.

- Liddicoat, Mary-Jane; Lennane, Richard; Abdul Rahim, Iman (2018). Syrian Colloquial Arabic: A Functional Course (Rev. 3rd ed. (online) ed.). M. Liddicoat. ISBN 978-0-646-49382-4. OCLC 732638712.

- Magidow, Alexander (2013). Towards a sociohistorical reconstruction of pre-Islamic Arabic dialect diversity (PhD thesis). University of Texas at Austin. hdl:2152/21378. OCLC 858998077.

- Versteegh, C. H. M. (2014). The Arabic Language. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4528-2. OCLC 872980196.

- Brustad, Kristen; Zuniga, Emilie (2019). "Chapter 16: Levantine Arabic". In Huehnergard, John; Pat-El, Na'ama (eds.). The Semitic Languages (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 403–432. doi:10.4324/9780429025563. ISBN 978-0-415-73195-9. OCLC 1103311755. S2CID 166512720.

- Cowell, Mark W. (1964). A Reference Grammar of Syrian Arabic. Georgetown University Press. OCLC 249229002.

- Płonka, Arkadiusz (2006). "Le nationalisme linguistique au Liban autour de Sa'īd 'Aql et l'idée de langue libanaise dans la revue Lebnaan en nouvel Alphabet". Arabica (in French). 53 (4). Brill: 423–471. doi:10.1163/157005806778915100.

- Abu Elhija, Duaa (2019). A Study of Loanwords and Code Switching in Spoken and Online Written Arabic by Palestinian Israelis (PhD thesis). Indiana University. ISBN 978-1-392-15264-5. OCLC 1151841166. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2021 – via ProQuest.

- Shachmon, Ori; Mack, Merav (2019). "The Lebanese in Israel – Language, Religion and Identity". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 169 (2). Harrassowitz Verlag: 343–366. doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.169.2.0343. JSTOR 10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.169.2.0343. S2CID 211647029.