Linear A

| Linear A | |

|---|---|

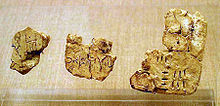

Linear A inscription on a cup | |

| Script type | Undeciphered

presumed logosyllabic (syllabic and ideographic) |

Time period | MM IB to LM IIIA 1800–1450 BC [1] |

| Status | Extinct |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | 'Minoan' (unknown) |

| Related scripts | |

Child systems | Linear B, Cypro-Minoan syllabary [2] |

Sister systems | Cretan hieroglyphs |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Lina (400), Linear A |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Linear A |

| "U+10600–U+1077F" (PDF). "Final Accepted Script Proposal" (PDF). | |

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 BC to 1450 BC. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It evolved into Linear B, which was used by the Mycenaeans to write an early form of Greek. It was discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1900. No texts in Linear A have yet been deciphered. Evans named the script "Linear" because its characters consisted simply of lines inscribed in clay, in contrast to the more pictographic characters in Cretan hieroglyphs that were used during the same period.[3]

Linear A belongs to a group of scripts that evolved independently of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian systems. During the second millennium BC, there were four major branches: Linear A, Linear B, Cypro-Minoan, and Cretan hieroglyphic.[4] In the 1950s, Linear B was deciphered and found to have an underlying language of Mycenaean Greek. Linear A shares many glyphs and alloglyphs with Linear B, and the syllabic glyphs are thought to notate similar syllabic values, but none of the proposed readings lead to a language that scholars can read.

Script

[edit]Linear A consists of over 300 signs including regional variants and hapax legomena. Among these, a core group of 90 occur with some frequency throughout the script's geographic and chronological extent.[5][6]

As a logosyllabic writing system, Linear A includes signs which stand for syllables as well as others standing for words or concepts. Linear A's signs could be combined via ligature to form complex signs. Complex signs usually behave as ideograms and most are hapax legomena, occurring only once in the surviving corpus. Thus, Linear A signs are divided into four categories:[5][6]

- syllabic signs

- ligatures and composite signs

- ideograms

- numerals and metrical signs

Linear A was usually written left-to-right, but a handful of documents were written right-to-left or boustrophedon.[5]

Signary

[edit]| *01–*20 | *21–*30 | *31–*53 | *54–*74 | *76–*122 | *123–*306 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

*01 |

*21 |

*31 |

*54 |

*76 |

*123 | ||||||

|

*02 |

*21 |

*34 |

*55 |

*77 |

*131a | ||||||

|

*03 |

*21 |

*37 |

*56 |

*78 |

*131b | ||||||

|

*04 |

*22 |

*38 |

*57 |

*79 |

*131c | ||||||

|

*05 |

*22 |

*39 |

*58 |

*80 |

*164 | ||||||

|

*06 |

*22 |

*40 |

*59 |

*81 |

*171 | ||||||

|

*07 |

*23 |

*41 |

*60 |

*82 |

*180 | ||||||

|

*08 |

*23 |

*44 |

*61 |

*85 |

*188 | ||||||

|

*09 |

*24 |

*45 |

*65 |

*86 |

*191 | ||||||

|

*10 |

*26 |

*46 |

*66 |

*87 |

*301 | ||||||

|

*11 |

*27 |

*47 |

*67 |

*100/ |

*302 | ||||||

|

*13 |

*28 |

*49 |

*69 |

*118 |

*303 | ||||||

|

*16 |

*28b |

*50 |

*70 |

*120 |

*304 | ||||||

|

*17 |

*29 |

*51 |

*73 |

*120b |

*305 | ||||||

|

*20 |

*30 |

*53 |

*74 |

*122 |

*306 | ||||||

Special signs

[edit]Furthermore, the following ‘supplementary’ syllabograms for more complex syllables can be identified (where in some cases the exact pronunciation is or used to be unknown even for Linear B, hence the use of subscript numbers):

| Special signs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | 𐘒 |

𐙄 |

𐘩 | 𐘰 |

𐘜 |

𐘽 |

𐘷 |

𐙆 |

| Transcription | pi2 | au | nwa | pa2 | pu2 | ra2 (rya) | ta2 (tya) | twe |

| Bennett's number | *22 | *85 | *48 | *56 | *29 | *76 | *66 | *87 |

Ideograms

[edit]The following list contains some frequent ideograms/logograms whose meaning is known and uncontroversial and almost all of which are preserved in Linear B.[9][10] The meaning of many others is debated. Note that some of the ideograms are also used as syllabograms; in such cases, the sound value is indicated in the table before the Bennett number.

| Glyph | Code point | Bennett | Conventional Latin name | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People and animals | ||||

| 𐙇 |

U+10647 | *100/102 | VIR

vir |

person, man |

| 𐘏 |

U+1060F | QI

*21 |

OVIS

ovis |

sheep |

| 𐘐 |

U+10610 | *21F | OVISf | ewe |

| 𐘑 |

U+10611 | *21M | OVISm | ram |

| 𐘒 |

U+10612 | PI2

*22 |

CAP

capra |

goat |

| 𐘓 |

U+10613 | *22F | CAPf | she-goat |

| 𐘔 |

U+10614 | *22M | CAPm | he-goat |

| 𐙄 |

U+10644 | AU

*85 |

SUS

sūs |

pig |

| 𐘕 |

U+10615 | MU

*23 |

BOS

bōs |

bovine |

| 𐘖 |

U+10616 | *23M | BOSm | ox/bull |

| Dry products | ||||

| 𐙉 |

U+10649 | *120 | GRA

grānum |

wheat |

| 𐙊 |

U+10649A | *120B | GRA

grānum |

wheat |

| 𐙋 |

U+1064B | *122 | OLIV

olīva |

olives |

| 𐘝 |

U+1061D | NI

*30 |

FIC

fīcus |

figs |

| 𐙗 |

U+10657 | *303 | CYP | cyperus |

| 𐘮 |

U+1062E | WA

*54 |

TELA

tēla |

cloth |

| Liquids | ||||

| 𐙖 |

U+10095 | *302 | OLE

ŏlĕum |

oil |

| 𐙍 |

U+1064D | *131A | VIN

vīnum |

wine |

| 𐙎 |

U+1064E | *131B | VIN

vīnum |

wine |

| 𐙏 |

U+1064F | *131C | VIN

vīnum |

wine |

| Vessels | ||||

| 𐚠 | U+106A0 | *400-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚡 | U+106A1 | *401-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚢 | U+106A2 | *402-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚣 | U+106A3 | *403-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚤 | U+106A4 | *404-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚥 | U+106A5 | *405-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚦 | U+106A6 | *406-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚧 | U+106A7 | *407-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚨 | U+106A8 | *408-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚩 | U+106A9 | *409-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚪 | U+106AA | *410-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚫 | U+106AB | *411-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚬 | U+106AC | *412-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚭 | U+106AD | *413-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚮 | U+106AE | *414-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚯 | U+106AF | *415-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚰 | U+106B0 | *416-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚱 | U+106B1 | *417-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| 𐚲 | U+106B2 | *418-VAS | VAS

vās |

- |

| Other | ||||

| 𐙔 |

U+10654 | *191 | GAL

galea |

helmet |

Numbers

[edit]Numbers follow a decimal system: units are represented by vertical dashes, tens by horizontal dashes, hundreds by circles, and thousands by circles with rays. There are special symbols to indicate fractions and weights. Specific signs that coincide with numerals are regarded as fractions;[11] these sign combinations are known as klasmatograms.[12]

Integers can be read and the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are quite straightforward, similarly to Roman numerals.[13]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 |

Fractions

[edit]There is a lack of scholarly agreement about signs, generally called klasmatograms, for Linear A fractions.[14][15][16][17] In 2021 Corazza et al. proposed the following values, most of which had been previously suggested:[18]

| Symbol | Glyph | Value |

|---|---|---|

| J | 1⁄2 | |

| E | 1⁄4 | |

| B | 1⁄5 | |

| D | 1⁄6 | |

| F | 1⁄8 | |

| K | 1⁄10 | |

| H | 1⁄16? | |

| L2 | 1⁄20 | |

| A | 1⁄24? | |

| L3 | 1⁄30 | |

| L4 | 1⁄40 | |

| L6 | 1⁄60 | |

| W | = BB? (2⁄5) | |

| X | = AA? (1⁄12) | |

| Y | ? | |

| Ω | ? |

Other fractions are composed by addition: the common JE and DD are 3⁄4 and 1⁄3 (2⁄6), BB = 2⁄5, EF = 3⁄8, etc. (and indeed B 1⁄5 looks like it might derive from KK 2⁄10). L, Y, and Ω are hapax legomena (only occur once) and it has been proposed that glyph L is spurious.[18]

Several of these values are supported by Linear B. Although Linear B used a different numbering system, several of the Linear A fractions were adopted as fractional units of measurement. For example, Linear B DD and (presumably AA) are 1⁄3 and 1⁄12 of a lana, while K is 1⁄10 of the main unit for dry weight.[18]

Corpus

[edit]

Linear A has been found chiefly on Crete, but also at other sites in Greece, as well as Turkey and Israel. The extant corpus, comprising some 1,427 specimens totals 7,362 to 7,396 signs. Linear A has been written on various media, such as stone offering tables and vessels, gold and silver hairpins, roundels, and ceramics.[19][20] The earliest inscriptions of Linear A come from Phaistos, in a layer dated at the end of the Middle Minoan II period: that is, no later than c. 1700 BC.[21][22] Linear A texts have been found throughout the island of Crete and also on some Aegean islands (Kythera, Kea, Thera, Melos), in mainland Greece (Ayos Stephanos), on the west coast of Asia Minor (Miletus, Troy), and in the Levant (Tel Haror, Tel Lachish).[23][24][25]

The first comprehensive compendium of Linear A inscriptions (sometimes referred to as GORILA) was produced by Louis Godart and Jean-Pierre Olivier in multiple columns between 1976 and 1985.[26][27][28][29][30] In 2011 work began on a supplement to that compendium.[31] In 2020 a project was begun, called SigLA, to put all the known Linear A inscriptions online at a single site.[32]

Tablets

[edit]

Essentially all Linear A tablets, most in a fragmentary condition, have been found on the island of Crete, dated to the Neopalatial Period. At that time Crete was divided by mountains and other geographic features into a number of polities, each with its own urban center.[33] These tablets have been found at Hagia Triada (147 tablets), Petras, Phaistos (26 tablets), Knossos (6 tablets), Petsophas, Archanes (7 tablets), Myrtos Pyrgos (2 tablets), Zakros (31 tablets), Tylissos (2 tablets), Malia (6 tablets), Gournia (1 tablet), and Khania (99 tablets).[34][35][36][37][38] One Linear A tablet was found on Kea in the Cyclades.[39] Three tablet fragments were found on the island of Santorini (Thera).[40] The handful of known Cretan Hieroglyphs tablets (with relatively few signs) were also found on Crete at Malia and Kato Symi.[41]

Sealed documents

[edit]

Seals and clay sealings served the same role of inventory control and ownership as in the ancient Near East and Egypt. Large numbers of sealings have been found, primarily on Crete and in the Late Minoan IB period. The primary sources of sealed documents come from Haghia Triada (1103), Zakros (560), Khania (210), Knossos (125), Phaistos (35), Malia (6), and Tylissos (5).[42][43][44] It is not clear what was commonly used to impress the sealing as only a few Linear A inscribed "seal stones" have been found. In other regions cylinder seals and stamp seals fulfilled this role.[45]

Sealed documents are divided by archaeologists into four classes:[35]

- Roundels – disks of clay with sealing on the edges[46]

- Hanging nodules – sealed lumps of clay originally attached to string[47]

- Parcel nodules – lumps of clay with sealing on back

- Noduli – clay lumps like hanging nodules but not formerly string attached

Libation tables

[edit]A group of Minoan finds, usually from sanctuaries, have traditionally been called libation tables. They come in full sized and miniature versions, usually of stone. Because of the findspots, at cultic sites like Mount Juktas, they are usually assumed to be religious in nature though that is not certain.[48] So far about 1000 libation tables have been recovered at 27 different sites on Crete, of which 41 have Linear A inscriptions.[49][50][51] These inscriptions follow a standardized "libation formula", a formula also found on a few other objects, primarily vessels.[52][53][54][55]

The "libation formula" has been much studied.[56][57] A similar construct in Cretan Hieroglyphs, the "Archanes Formula", is the main proposed link to Linear A.[58]

Other sources

[edit]

While most of the recovered Linear A signs have come from tablets, libation tables and related ritual objects, and sealed documents, a number of very short Linear A inscriptions have been found in the Minoan area of operation, primarily in the form of potmarks and mason's marks.[59] A problem is that it can be difficult to tell if a single-sign (or even doubleton) is Linear A, Linear B, or Cretan Hieroglyphs because of the overlap in sign use.[60][61] Vessel sherds were found at Traostalos, bearing three signs in total.[62] Four vase sherds were found at Thera with signs, as well as a ostrakon with one sign.[40] A vessel fragment was found at Miletus.[63] Two pithoi with very fragmentary inscriptions were found at Pseira.[64] Graffiti has been found at places like Hagia Triada.[65] A small clay ball with three Linear A signs was found at Mikro Vouni on the island of Samothrace.[66] A small stone tab with two signs was excavated in Hagios Stephanos, Laconia.[67] A silver hair pin and a gold ring, both with fairly long Linear A inscriptions, were found at Mavro Spelio in Knossos.[68][24][69]

A Linear A inscription was said to have been found in southeast Bulgaria.[70] Another, somewhat more solid, find was at Tel Lachish.[71] A Minoan graffito found at Tel Haror on a vessel fragment is either Linear A or Cretan hieroglyphs.[72]

Several tablets inscribed in signs similar to Linear A were found at Troy in northwestern Anatolia. While their status is disputed, they may be imports, as there is no evidence of Minoan presence in the Troad. Classification of these signs as a unique Trojan script (proposed by contemporary Russian linguist Nikolai Kazansky) is not accepted by other linguists.[73][74] Two Linear A inscribed clay spindle whorls were also found at Troy.[75]

Chronology

[edit]The earliest attestation of Linear A begins around 1800 BC (Middle Minoan IB) during the Protopalatial period. It became prominent around 1625 BC (Middle Minoan IIIB) and went out of use around 1450 BC (Late Minoan I) during the Neopalatial period. It was contemporary with and possibly derived from Cretan hieroglyphs, and may be an ancestor of Linear B. The Cypro-Minoan syllabary, used between Cyprus and its trading partners around the Mediterranean, was also in use during this period.[76] The sequence and the geographical spread of Cretan hieroglyphs, Linear A, and Linear B, the three overlapping but distinct writing systems on Bronze Age Crete and the Greek mainland, can be summarized as follows:[77]

| Writing system | Geographical area | Time span |

|---|---|---|

| Cretan Hieroglyphic | Crete, Samothrace | c. 2100–1700 BC |

| Linear A | Crete, Aegean islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and Greek mainland (Laconia) | c. 1800–1450 BC |

| Cypro-Minoan | Cyprus and trading partners, Ugarit | c. 1550–1050 BC |

| Linear B | Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) | c. 1450–1200 BC |

Decipherment

[edit]

Linear A has not been fully deciphered. However, researchers are reasonably confident in the approximate sound values of most syllabic signs and are able to make inferences about the meanings of some texts.[5][6][78]

Challenges to decipherment

[edit]One major barrier to its decipherment is the limited surviving corpus. Only around 1400 Linear A inscriptions survive, in contrast to the 6000 available for Linear B. As a result, researchers are stuck with limited sample sizes, making it difficult to reliably detect patterns.[5][6][79] Similarly, Linear A inscriptions are often fragmentary, damaged, or otherwise hard to read. It can be difficult to individuate particular signs and to distinguish separate signs from handwriting variants.[5][6][79] Finally, Linear A inscriptions tend to be brief and repetitive. Rather than complete sentences, many are lists where each entry consists of a toponym or personal name followed by a logogram and then a numeral. Thus, the surviving corpus contains few spelled-out words and limited evidence of the grammatical structure.[5][6][19]

A second barrier is the scarcity of external evidence. No bilingual inscriptions have been found, preventing the script from being deciphered in the manner that Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered using the Rosetta Stone.[5][6] The underlying language of Linear A has not been determined, and it is not clear that the same language was used for its entire period of use. The grammatical evidence that can be gleaned from the surviving corpus suggests that it was not a close relative of any known language.[5][6]

Phonetic values

[edit]For most of Linear A's syllabic signs, approximate sound values can be inferred based on the values of homomorphic signs in Linear B. These sound values are widely accepted by current researchers, though they are not considered incontrovertible and many details remain up for debate. This does not amount to a complete decipherment since it results in words that are uninterpretable.[5][6][80][78]

These values are based on the homomorphy-homophony principle which states that in related writing systems, signs with similar forms will generally have similar phonetic values. Although this principle is not reliable across the board, there are a number of strong reasons why scholars have concluded that it does generally hold in Linear A.[81] One reason is that is already known to hold in many cases between Linear B and the Cypriot syllabary, another script which descends from Linear A. This fact suggests that these signs were inherited by both scripts along with their Linear A phonetic values.[82] A second reason is that the resulting Linear A sound values provide readings of words which match what contextual analysis would lead us to expect. For instance, words which contextual analysis suggests to be placenames are read as such when assuming Linear B values. Notably, the Linear A word 𐘂𐘚𐘄 would be read as Pa-i-to, corresponding to the placename Phaistos attested in the Linear B corpus as 𐀞𐀂𐀵 Pa-i-to.[5][6][83][84][85]

However, in particular cases scholars have identified reasons to expect divergence in pronunciation. Some scholars have argued that Minoan did not really have a vowel phoneme /o/, that it may not have had the labialised velars that the q-signs express in Mycenaean, and that the only apparent voiced stop, d, was really a dental fricative in Minoan.[86]

The following table shows signs that are known to be syllabograms and for which provisional and approximate sound values are assumed primarily based on the known pronunciations of identical or similar signs in Linear B.[86][87][88]

While many of those assumed to be syllabic signs are similar to ones in Linear B, approximately 80% of Linear A's logograms are unique;[89][4] the difference in sound values between Linear A and Linear B signs ranges from 9% to 13%.[90]

Underlying language

[edit]

Linear A does not appear to encode any known language. The placeholder term Minoan language is often used, though it is not certain that the texts are all in the same language.[5][91] Minoan appears to be agglutinative, making copious use of prefixes and suffixes. It likely had a three vowel system, since it shares Linear B's /i/, /u/, and /a/ series, but not Linear B's /o/ series and not all of its /e/ series.[5] Based on regularities in the Linear A Libation Formulas, it has been argued that its word order was Verb Subject Object.[92][93][5]

Scholars have noted a number of potential parallels between Minoan and Anatolian languages such as Luwian and Lycian, as well as with Semitic languages such as Phoenician and Ugaritic. However, even if these connections are not coincidental, it is unclear whether Minoan is related to one of these languages or if the parallels arose through language contact.[5][94][95][96][39]

Unicode

[edit]The Linear A alphabet (U+10600–U+1077F) was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0. Current as of the latest Unicode version, 15.1.[97]

| Linear A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1060x | 𐘀 | 𐘁 | 𐘂 | 𐘃 | 𐘄 | 𐘅 | 𐘆 | 𐘇 | 𐘈 | 𐘉 | 𐘊 | 𐘋 | 𐘌 | 𐘍 | 𐘎 | 𐘏 |

| U+1061x | 𐘐 | 𐘑 | 𐘒 | 𐘓 | 𐘔 | 𐘕 | 𐘖 | 𐘗 | 𐘘 | 𐘙 | 𐘚 | 𐘛 | 𐘜 | 𐘝 | 𐘞 | 𐘟 |

| U+1062x | 𐘠 | 𐘡 | 𐘢 | 𐘣 | 𐘤 | 𐘥 | 𐘦 | 𐘧 | 𐘨 | 𐘩 | 𐘪 | 𐘫 | 𐘬 | 𐘭 | 𐘮 | 𐘯 |

| U+1063x | 𐘰 | 𐘱 | 𐘲 | 𐘳 | 𐘴 | 𐘵 | 𐘶 | 𐘷 | 𐘸 | 𐘹 | 𐘺 | 𐘻 | 𐘼 | 𐘽 | 𐘾 | 𐘿 |

| U+1064x | 𐙀 | 𐙁 | 𐙂 | 𐙃 | 𐙄 | 𐙅 | 𐙆 | 𐙇 | 𐙈 | 𐙉 | 𐙊 | 𐙋 | 𐙌 | 𐙍 | 𐙎 | 𐙏 |

| U+1065x | 𐙐 | 𐙑 | 𐙒 | 𐙓 | 𐙔 | 𐙕 | 𐙖 | 𐙗 | 𐙘 | 𐙙 | 𐙚 | 𐙛 | 𐙜 | 𐙝 | 𐙞 | 𐙟 |

| U+1066x | 𐙠 | 𐙡 | 𐙢 | 𐙣 | 𐙤 | 𐙥 | 𐙦 | 𐙧 | 𐙨 | 𐙩 | 𐙪 | 𐙫 | 𐙬 | 𐙭 | 𐙮 | 𐙯 |

| U+1067x | 𐙰 | 𐙱 | 𐙲 | 𐙳 | 𐙴 | 𐙵 | 𐙶 | 𐙷 | 𐙸 | 𐙹 | 𐙺 | 𐙻 | 𐙼 | 𐙽 | 𐙾 | 𐙿 |

| U+1068x | 𐚀 | 𐚁 | 𐚂 | 𐚃 | 𐚄 | 𐚅 | 𐚆 | 𐚇 | 𐚈 | 𐚉 | 𐚊 | 𐚋 | 𐚌 | 𐚍 | 𐚎 | 𐚏 |

| U+1069x | 𐚐 | 𐚑 | 𐚒 | 𐚓 | 𐚔 | 𐚕 | 𐚖 | 𐚗 | 𐚘 | 𐚙 | 𐚚 | 𐚛 | 𐚜 | 𐚝 | 𐚞 | 𐚟 |

| U+106Ax | 𐚠 | 𐚡 | 𐚢 | 𐚣 | 𐚤 | 𐚥 | 𐚦 | 𐚧 | 𐚨 | 𐚩 | 𐚪 | 𐚫 | 𐚬 | 𐚭 | 𐚮 | 𐚯 |

| U+106Bx | 𐚰 | 𐚱 | 𐚲 | 𐚳 | 𐚴 | 𐚵 | 𐚶 | 𐚷 | 𐚸 | 𐚹 | 𐚺 | 𐚻 | 𐚼 | 𐚽 | 𐚾 | 𐚿 |

| U+106Cx | 𐛀 | 𐛁 | 𐛂 | 𐛃 | 𐛄 | 𐛅 | 𐛆 | 𐛇 | 𐛈 | 𐛉 | 𐛊 | 𐛋 | 𐛌 | 𐛍 | 𐛎 | 𐛏 |

| U+106Dx | 𐛐 | 𐛑 | 𐛒 | 𐛓 | 𐛔 | 𐛕 | 𐛖 | 𐛗 | 𐛘 | 𐛙 | 𐛚 | 𐛛 | 𐛜 | 𐛝 | 𐛞 | 𐛟 |

| U+106Ex | 𐛠 | 𐛡 | 𐛢 | 𐛣 | 𐛤 | 𐛥 | 𐛦 | 𐛧 | 𐛨 | 𐛩 | 𐛪 | 𐛫 | 𐛬 | 𐛭 | 𐛮 | 𐛯 |

| U+106Fx | 𐛰 | 𐛱 | 𐛲 | 𐛳 | 𐛴 | 𐛵 | 𐛶 | 𐛷 | 𐛸 | 𐛹 | 𐛺 | 𐛻 | 𐛼 | 𐛽 | 𐛾 | 𐛿 |

| U+1070x | 𐜀 | 𐜁 | 𐜂 | 𐜃 | 𐜄 | 𐜅 | 𐜆 | 𐜇 | 𐜈 | 𐜉 | 𐜊 | 𐜋 | 𐜌 | 𐜍 | 𐜎 | 𐜏 |

| U+1071x | 𐜐 | 𐜑 | 𐜒 | 𐜓 | 𐜔 | 𐜕 | 𐜖 | 𐜗 | 𐜘 | 𐜙 | 𐜚 | 𐜛 | 𐜜 | 𐜝 | 𐜞 | 𐜟 |

| U+1072x | 𐜠 | 𐜡 | 𐜢 | 𐜣 | 𐜤 | 𐜥 | 𐜦 | 𐜧 | 𐜨 | 𐜩 | 𐜪 | 𐜫 | 𐜬 | 𐜭 | 𐜮 | 𐜯 |

| U+1073x | 𐜰 | 𐜱 | 𐜲 | 𐜳 | 𐜴 | 𐜵 | 𐜶 | |||||||||

| U+1074x | 𐝀 | 𐝁 | 𐝂 | 𐝃 | 𐝄 | 𐝅 | 𐝆 | 𐝇 | 𐝈 | 𐝉 | 𐝊 | 𐝋 | 𐝌 | 𐝍 | 𐝎 | 𐝏 |

| U+1075x | 𐝐 | 𐝑 | 𐝒 | 𐝓 | 𐝔 | 𐝕 | ||||||||||

| U+1076x | 𐝠 | 𐝡 | 𐝢 | 𐝣 | 𐝤 | 𐝥 | 𐝦 | 𐝧 | ||||||||

| U+1077x | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ Palaima 1997, pp. 121–188.

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (2009). Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-9-40-215757-4.

- ^ a b Packard 1974, Chapter 1: Introduction.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Salgarella, Ester (2022). "Linear A". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8927.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tomas, Helena (2012). "Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 113–125. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0026. ISBN 978-0199873609.

- ^ https://sigla.phis.me/search-attestation.html#attestation:.[att-site%20@%20!unit:]%20(belongs-location%20@%20![location]:[])%20&&%20.[att-type%20@%20!unit:]%20(belongs-kind%20@%20![kind]:[])%20&&%20sign-match%20@%20!reading-pattern:(A559,%20false)//[att-site:groupResult\/;occ-doc-name:sort/\]

- ^ Bennett, E. L. Jr., "Mycenaean Studies Proceedings of the Third International Colloquium for Mycenaean Studies held at 'Wingspread', 4—8 September 1961", ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964

- ^ Younger, John. Linear A. 11. Ideograms/Logograms. Archived from the original

- ^ Linear A. Range: 10600–1077F. The Unicode Standard, Version 15.1

- ^ Packard 1974, pp. 23–24

- ^ Proust, Christine (22 June 2009). "Numerical and Metrological Graphemes: From Cuneiform to Transliteration". Cuneiform Digital Library Journal. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Anderson, W. French (1 July 1958). "Arithmetical Procedure in Minoan Linear A and in Minoan-Greek Linear B". American Journal of Archaeology. 62 (3): 363–368. doi:10.2307/501989. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 501989. S2CID 193020404.

- ^ Billigmeier, Jon C. (1 October 1973). "Linear A Fractions: A New Approach". American Journal of Archaeology. 77 (1): 61–65. doi:10.2307/503234. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 503234. S2CID 191382050.

- ^ Bennett, Emmett L. (1 January 1980). "Linear A fractional retractation". Kadmos. 19 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1515/kadmos-1980-0104. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 163961065.

- ^ Schrijver, Peter (1 July 2014). "Fractions and food rations in Linear A". Kadmos. 53 (1–2): 1–44. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2014-0001. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 164932371.

- ^ Giulio Facchetti, "Linear A metrograms", Kadmos, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 142-148, 1994

- ^ a b c d Corazza, Michele; Ferrara, Silvia; Montecchi, Barbara; Tamburini, Fabio; Valério, Miguel (2021). "The mathematical values of fraction signs in the Linear A script: A computational, statistical and typological approach". Journal of Archaeological Science. 125: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105214. hdl:11585/789546. S2CID 225229514.

- ^ a b Winterstein, Gregoire; Cacciafoco, Francesco Perono; Petrolito, Ruggero; Petrolito, Tommaso (2015). "Minoan linguistic resources: The Linear A digital corpus". Proceedings of the 9th SIGHUM Workshop on Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities (LaTeCH) – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Brent Davis, Minoan Stone Vessels with Linear A Inscriptions. AEGAEUM, 36. Leuven; Liège: Peeters, 2014. xxiv, 421. ISBN 9789042930971

- ^ Hutchinson R.W., "Prehistoric Crete", London, 1962

- ^ Pugliese Carratelli G, "Nouve epigrafi minoiche da Festo", Annuario della Scuola Archaeologica di Atene 35-36[n.s. 19-20(1957-1958)], pp. 363-388, 1958

- ^ Woudhuizen, Fred C. (2016). Documents in Minoan Luwian, Semitic, and Pelasgian. Amsterdam: Nederlands Archeologisch Historisch Genootschap. ISBN 9789072067197. OCLC 1027956786.

- ^ a b Cacciafoco, Francesco Perono (January 2014). Linear A and Minoan. The riddle of unknown origins. Linear a and Minoan. The Riddle of Unknown Origins (slides). Retrieved 13 July 2020 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ [1] Sampson, Adamantios, "Symbols of Minoan Hieroglyphic Script and Linear A in Melos from the Middle of 3rd Millennium BC", Annals of Archaeology 5.1, pp. 1–10, 2023

- ^ Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P., "Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 1: Tablettes editees avant 1970", Paris, 1976

- ^ Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P., "Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 2: Nodules, scelles et rondelles edites avant 1970", Paris, 1979

- ^ Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P., "Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 3: Tablettes, nodules et rondelles edites en 1975 et 1976", Paris, 1976

- ^ Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P., "Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 4: Autres documents", Paris, 1982

- ^ Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P., "Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 5: Addenda, corrigenda, concordances, index et planches des signes", Paris, 1985

- ^ [2] Del Freo M. and Zurbach J., "La préparation d’un supplément au Recueil des inscriptions en linéaire A. Observations à partir d’un travail en cours", BCH 135.1, pp. 73–97, 2011

- ^ [3] Ester Salgarella and Simon Castellan, "SigLA The Signs of Linear A: a palæographical database", August 20, 2020

- ^ E Kyriakidis, "Undeciphered tablets and undeciphered territories: A comparison of late minoan IB archives", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society, no. 49, pp. 118–29, 2003,

- ^ Gallimore, S., and K.T. Glowacki. “Stratigraphic Excavations within the Gournia Palace 2011-2014.” [Abstract]. Archaeological Institute of America 119th Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America Volume 41 (2017), 345. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America

- ^ a b [4] Salgarella, Ester, "Drawing lines: The palaeography of Linear A and Linear B", Kadmos, vol. 58, no. 1–2, pp. 61–92, 2019 doi:10.1515/kadmos-2019-0004

- ^ Hallager, Erik; Andreadaki-Vlazaki, Maria (1 July 2018). "Some unpublished Linear A documents from Khania". Kadmos. 57 (1–2): 33–44. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2018-0004. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 204963634.

- ^ Schoep 1999, pp. 201–221.

- ^ Anna Morpurgo-Davies, Gerald Cadogan, "A second Linear A tablet from Pyrgos" Kadmos, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 7-9, 1977

- ^ a b Finkelberg 1998, pp. 265–272.

- ^ a b Bennett, Simon M. and Owens, Gareth A., "The Dating of the Linear A Inscriptions from Thera", Kadmos, vol. 38, no. 1–2, pp. 12–18, 1999

- ^ A. Lembessi, P. Muhly, and J.-P. Olivier, "An Inscription in the Hieroglyphic Script from the Syme Sanctuary, Crete (Sy Hf 01)" Kadmos, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 63-77, 1995

- ^ Schoep, Ilse (1999). "Tablets and Territories? Reconstructing Late Minoan IB Political Geography through Undeciphered Documents". American Journal of Archaeology. 103 (2): 201–221. doi:10.2307/506745. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 506745. S2CID 155632843.

- ^ Weingarten, Judith, "Seal-use at LM IΒ Ayia Triada: a Minoan elite in action I. Administrative considerations", Kadmos 26.1, pp. 1-43, 1987

- ^ Massimo Perna, "The Roundels of Haghia Triada", Kadmos, 33, pp. 93-141 1994

- ^ Civitillo, Matilde (2023). "Comparing Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A seal stones: a preliminary assessment of forms, materials, sequences, uses". Ariadne Supplement Series. ISSN 2623-4726.

- ^ Erik Hallager, The Minoan Roundel and Other Sealed Documents in the Neopalatial Linear A Administration, Peeters Publishers, 31 Dec 1996 ISBN 9789042924130

- ^ [5] Tsipopoulou, Metaxia, and Erik Hallager, "The nodules and their types-definitions and discussions", Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens (MoDIA) 9, pp. 182–194, 2010

- ^ Metaxa-Muhly, Polymnia, "Linear A inscriptions from the Sanctuary of Hermes and Aphrodite at Kato Syme", Kadmos, vol. 23, no. 1-2, pp. 124-135, 1984

- ^ Monti, Orazio, "Some observations on the language of Linear A", Kadmos, vol. 61, no. 1-2, pp. 107–116, 2022

- ^ Driessen, Jan, "A fragmentary linear a inscription from petsophas, palaikastro (pk za 20)", Kadmos, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 149–152, 1994

- ^ C. Davaras and W. C. Brice, "A Fragment of a Libation Table Inscribed in Linear A from Vrysinas", Kadmos, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 5-6, 1977

- ^ Platon, Nikolas, "Inscribed libation vessel from a Minoan house at Prassa, Heraklion", Minoica: Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Johannes Sundwall, edited by Ernst Grumach, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 305-318, 1958

- ^ Davaras, Costis, "Three New Linear A Libation Vessel Fragments from Petsophas", Kadmos, vol. 20, no. 1-2, 1981, pp. 1-6, 1981

- ^ Stylianos Alexiou, W. Brice, "A Silver Pin from Platanos with an inscription in Linear A: Her. Mus. 498". Kadmos, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 18-27, 1976

- ^ Leinwand, Nancy Westneat, "A Ladle from Shaft Grave III at Mycenae", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 519–21, 1980

- ^ W. C. Brice, "The Minoan “Libation Formula”", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 48.1 (1965)

- ^ Thomas, Rose (1 December 2020). "Some reflections on morphology in the language of the Linear A libation formula" (PDF). Kadmos. 59 (1–2): 1–23. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2020-0001. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 235451899.

- ^ Ferrara, Silvia; Montecchi, Barbara; Valério, Miguel (December 2021). "What is the 'Archanes Formula'? Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Earliest Attestation of Writing in the Aegean". Annual of the British School at Athens. 116: 43–62. doi:10.1017/S0068245420000155. hdl:11585/833390. ISSN 0068-2454. S2CID 236307210.

- ^ Militello P.M., "Management, power and non-literate communication in Prepalatial and Palatial Messara", in A. M. Jasink – J. Weingarten – S. Ferrara (a cura di), Non-scribal Communication Media in the Bronze Age Aegean and Surrounding Areas. The semantics of a-literate and proto-literate media, Firenze, pp. 55-72, 2017

- ^ [6] Santamaria, Andrea, "From images to signs: Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A in context." (2023, Dissertation, Università di Bologna, 2023

- ^ Owens, Gareth A., "The Common Origin of Cretan Hieroglyphs and Linear A", Kadmos, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 105-110, 1996

- ^ Davaras, Costis, "Three sherds inscribed in Linear A, from Traostalos", Kadmos, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 167-167, 1974

- ^ Niemeier, Wolf-Dietrich, "A Linear A Inscription from Miletus (MIL Zb 1)", Kadmos, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 87–99, 1996

- ^ Floyd, Cheryl R., "Fragments from two pithoi with Linear A inscriptions from Pseira", Kadmos, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 39–48, 1995

- ^ Cameron, Mark A. S., "Four Fragments of Wall Paintings with Linear A Inscriptions", Kadmos, vol. 4, no. 1, 1965, pp. 7-15

- ^ D. Matsas, "Samothrace and the Northeastern Aegean: The Minoan Connection", Studia Troica 1, pp. 159-179, 1991

- ^ R. Janko, "The Linear A Inscription", in Ayios Stephanos: Excavations at a Bronze Age and Medieval Settlement in Southern Laconia, The British School at Athens. Supplementary Volumes, no. 44, pp. 441-443, 2008

- ^ Alexiou Stylianos and Brice William C., "A Silver Pin from Mavro Spelio with an Inscription in Linear A: Her. Mus. 540", Kadmos, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 113-124, 1972

- ^ Pullen, Daniel J. (2009). "[Review of] W.D. Taylour & R. Janko, Ayios Stephanos: Excavations at a Bronze Age and Medieval Settlement in Southern Laconia. British School at Athens, 2008". Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- ^ Fol, Alexander, Schmitt, Sofia and Schmitt, Rüdiger. "A Linear A Text on a Clay Reel from Drama, South-East Bulgaria?", Praehistorische Zeitschrift, vol. 75, no. 1, 2000, pp. 56–62

- ^ Finkelberg et al. 1996: M. Finkelberg/A. Uchitel/D. Ussishkin, A Linear A Inscription from Tel Lachish (LACH Za 1). TelAviv 23, 1996, 195–207

- ^ Olivier, Jean-Pierre. "A Minoan graffito from Tel Haror (Negev, Israel)." Cretan studies 5 (1996): 98–109

- ^ Schliemann, Heinrich; Smith, Philip; Schmitz, L. Dora (1875). Troy and its remains; a narrative of researches and discoveries made on the site of Ilium, and in the Trojan plain. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. London, J. Murray. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kazansky, NN. (1984). Bernstein, S.B.; Gindin, L.A.; Golubtsova, E.S.; I.A.; Orel, V.E.) (eds.). Троянское письмо: к постановке вопроса (in Russian).

- ^ L. Godart, La scrittura di Troia. Rendicontidella Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche dell'Ac-cademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Ser. IX, 5, 1994, pp. 457–460, 1994

- ^ Valério, Miguel, "Linear A du and Cypriot su: a Case of Diachronic Acrophony?", Kadmos, vol. 47, no. 1-2, pp. 57-66, 2009

- ^ Olivier 1986, pp. 377f.

- ^ a b Salgarella, Ester (17 June 2022). "Cracking the Cretan code". Aeon. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

Linear A is, after all, 'partially deciphered', inasmuch as we can read the texts in phonetic transcription with some approximation, understand some of the words... and get a general idea of the documents' contents.

- ^ a b Salgarella, Ester (17 June 2022). "Cracking the Cretan code". Aeon. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ [7] Meissner, T., & Steele, P., "Linear A and Linear B: Structural and contextual concerns", Edizioni Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 2017

- ^ Salgarella, Ester (2020). Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship between Linear A and Linear B. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-108-47938-7.

- ^ Salgarella, Ester (2020). Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship between Linear A and Linear B. Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-108-47938-7.

- ^ Hooker, J. T. "Problems and Methods in the Decipherment of Linear A.", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 2, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1975, pp. 164–72

- ^ Younger, John (2000). "10c. Place names". Linear A texts in phonetic transcription. University of Kansas. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ Finkelberg, Margalit (2001). "The Language of Linear A: Greek, Semitic, or Anatolian?". In Drews, Robert (ed.). Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language Family. Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph Series. Vol. 38. pp. 81–105. ISBN 978-0941694773 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Davis, Brent. 2010. Introduction to Aegean pre-Alphabetic Scripts. Kubaba 1, pp.38-61.. P. 51-54.

- ^ Fang, X.M., Perono Cacciafoco, F., and Cavallaro, F.P. (2021). Some Remarks on Grammatological and Morphological Aspects of Linear A Documents: An Internal Analysis Approach. Annals of the University of Craiova: Series Philology, Linguistics, 43(1), pp. 316-338. P.319.

- ^ van Soesbergen, Peter George. 2016. Minoan Linear A – volume I. Hurrians and Hurrian in Minoan Crete. Part 1: text. P.3-10.

- ^ Younger, John (2000). "7b. The Script". Linear A texts in phonetic transcription. University of Kansas. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Owens 1999, pp. 23–24 (David Packard, in 1974, calculated a sound-value difference of 10.80 ± 1.80%, Yves Duhoux, in 1989, calculated a sound-value difference of 14.34% ± 1.80% and Gareth Owens, in 1996, calculated a sound-value difference of 9–13%).

- ^ Chadwick J., "Introduction to the problems of ‘Minoan Linear A’", JRAS 2, pp. 143–147, 1975

- ^ Davis, Brent (1 December 2013). "Syntax in Linear A: The Word-Order of the 'Libation Formula'". Kadmos. 52 (1): 35–52. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2013-0003. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 163948869.

- ^ How do you crack the code to a lost ancient script? - Andrew Trounson, University of Melbourne - 5 November 2019

- ^ Jan Best, "The First Inscription in Punic. Vowel Differences between Linear A and B, Ugarit-Forschungen 32, pp. 27-35, 2000

- ^ Dietrich & Loretz 2001.

- ^ Palmer, Leonard Robert (1958). "Luvian and Linear A". Transactions of the Philological Society. 57 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1958.tb01273.x. ISSN 0079-1636.

- ^ [8] Michael Everson, "N3973: Revised proposal for encoding the Linear A script in the SMP of the UCS", Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2, 2010-12-28

Works cited

[edit]- Chadwick, John (1967). The Decipherment of Linear B. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39830-5.

- Cook, Mark. (2022). Rewriting History: The decipherment of Linear A and a history of Egypto-Cretan relations in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Sydney: self-published. ISBN 978-0-646-86541-6.

- Dietrich, Manfried; Loretz, Oswald (2001). In Memoriam: Cyrus H. Gordon. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-934628-00-7.

- Facchetti, Giulio M.; Negri, Mario (2003). Creta Minoica: Sulle tracce delle più antiche scritture d'Europa (in Italian). Firenze: L.S. Olschki. ISBN 978-88-222-5291-3.

- Finkelberg, Margalit (1998). "Bronze Age Writing: Contacts between East and West" (PDF). In Cline, E.H.; Harris-Cline, D. (eds.). The Aegean and the Orient in the Second Millennium. Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Symposium, Cincinnati, 18–20 April 1997. Liège 1998. Aegeum. Vol. 18. pp. 265–272. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- Georgiev, Vladimir I. (1963). "Les deux langues des inscriptions crétoises en linéaire A". Linguistique Balkanique (in French). 7 (1): 1–104.

- Nagy, Gregory (1963). "Greek-Like Elements in Linear A". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 4 (4). Durham: Duke University Press: 181–211. ISSN 2159-3159.

- Olivier, J.P. (1986). "Cretan Writing in the Second Millennium B.C." World Archaeology. 17 (3): 377–389. doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979977. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Owens, Gareth (1999). "The Structure of the Minoan Language" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 27 (1–2): 15–56. ISSN 0092-2323. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Owens, Gareth Alun (2007). "Η Δομή της Μινωικής Γλώσσας" [The Structure of the Minoan Language] (PDF) (in Greek). Heraklion: TEI of Crete –Daidalika. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Packard, David W. (1974). Minoan Linear A. Berkeley / Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02580-6.

- Palaima, Thomas G. (1997) [1989]. "Cypro-Minoan Scripts: Problems of Historical Context". In Duhoux, Yves; Palaima, Thomas G.; Bennet, John (eds.). Problems in Decipherment. Louvain-La-Neuve: Peeters. pp. 121–188. ISBN 978-90-6831-177-8.

- Palmer, Leonard Robert (1958). "Luvian and Linear A". Transactions of the Philological Society. 57 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1958.tb01273.x. ISSN 0079-1636.

- Yatsemirsky, Sergei A. (2011). Opyt sravnitel'nogo opisaniya minoyskogo, etrusskogo i rodstvennyh im yazykov [Tentative Comparative Description of Minoan, Etruscan and Related Languages] (in Russian). Moscow: Yazyki slavyanskoy kul'tury. ISBN 978-5-9551-0479-9.

Further reading

[edit]- John Bennet, "Now You See It; Now You Don’t! The disappearance of the Linear A script on Crete", In: The Disappearance of Writing Sys- tems:Perspectives on Literacy and Communication. Ed. by John Baines, John Bennet, and Stephen Houston. London and Oakville, pp. 1–29, 2008

- Best, Jan G. P. (1972). Some Preliminary Remarks on the Decipherment of Linear A. Amsterdam: Hakkert.

- [9]Braović, Maja, et al., "A Systematic Review of Computational Approaches to Deciphering Bronze Age Aegean and Cypriot Scripts", Computational Linguistics, pp. 1-54, 2024

- Brice, William C., "Notes on Linear A". Kadmos, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 81–106, 1983

- Brice, William C., "Some observations on the linear A inscriptions", Kadmos, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 42–48, 1962

- G.P. Carratelli, "Le epigraphi di Haghia Triada in lineare A", Salamanca, 1963

- Davis, S. (March 1959). "New Light on Linear A". Greece & Rome. 6 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1017/S0017383500013231. ISSN 1477-4550. JSTOR 641970. S2CID 162763789.

- Facchetti, Giulio M. (2003). "On Some Recent Attempts to Identify Linear A Minoan Language". Minos (37–38): 89–94. ISSN 0544-3733.

- Gordon, Cyrus H., "Further Notes on the Hagia Triada Tablet no. 31", Kadmos, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 28-30, 1976

- Gordon, Cyrus H., "The Language of the Hagia Triada Tablets", Klio, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 63-68, 1960

- Gordon, Cyrus H. (1958). "Minoan Linear A". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 17 (4): 245–255. doi:10.1086/371479. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 542386. S2CID 161866359.

- Ferrara, Silvia; Valério, Miguel; Montecchi, Barbara (2022). "The Relationship between Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A: a palaeographic and structural approach" (PDF). Pasiphae – Journal of Aegean Philology and Antiquity. 26 (16): 81–109. doi:10.19272/202233301006. ISSN 2037-738X.

- Judson, A. P. (2020). The Undeciphered Signs of Linear B. Interpretation and Scribal Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108796910.

- Kvashilava, Gia (2019). On Decipherment of the Inscriptions of Linear A in the Common Kartvelian Language: ku-ro and ki-ro [10]

- Marangozis, John (2007). An introduction to Minoan linear A. München: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-386-8.

- Militello, Pietro, "Ayia Triada tablets, findspots and scribes. A reappraisal", Pasiphae, vol. 000, no. 005, pp. 59–69, 2011

- P. Militello, "Riconsiderazioni preliminari sulla documentazione in Lineare A da Haghia Triadaî", Sileno, 14, pp. 233-261, 1988

- Montecchi, Barbara, "Linear a Banqueting Lists?", Kadmos, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 2012

- Montecchi, Barbara (January 2010). "A Classification Proposal of Linear A Tablets from Haghia Triada in Classes and Series". Kadmos. 49 (1): 11–38. doi:10.1515/KADMOS.2010.002. ISSN 0022-7498. S2CID 124902710.

- Montecchi, Barbara (1 February 2022). "Rebus compositions in Linear A?". Kadmos. 61 (1–2): 97–106. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2022-0004.

- Nagy, Gregory (October 1965). "Observations on the Sign-Grouping and Vocabulary of Linear A". American Journal of Archaeology. 69 (4): 295–330. doi:10.2307/502181. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 502181. S2CID 191385596.

- Notti, Erika (2010). "The Theran Epigraphic Corpus of Linear A : Geographical and Chronological Implications". Pasiphae (4): 93–96. doi:10.1400/168368. ISSN 2037-738X.

- Notti, Erika, "Writing in Late Bronze Age Thera. Further Observations on the Theran Corpus of Linear A", Pasiphae, vol. 000, no. 015, 2021 ISSN: 2037-738X

- Palmer, Ruth (1995). "Linear A Commodities: A Comparison of Resources" (PDF). Aegeum. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Salgarella, Ester (2020). Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship between Linear A and Linear B. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108479387.

- Schoep, Ilse (2002). "The Administration of Neopalatial Crete. A Critical Assessment of the Linear A Tablets and their Role in the Administrative Process". Minos (Supplementary Volume no. 17). Salamanca: 1–230. ISSN 0544-3733. OCLC 52610144.

- van Soesbergen, Peter (2016). "Part 1, Text". Hurrians and Hurrian in Minoan Crete. Minoan Linear A. Vol. I. Amsterdam: Brave New Books. ISBN 978-0-19-956778-2.

- [11]Tomas, Helena, "The Administration of Haghia Triada", Opvscvla archaeologica 25.1, pp. 39-57, 2001

- Thomas, Helena (2003). Understanding the transition from Linear A to Linear B script (D. Phil. thesis). University of Oxford. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Supervisor: Professor John Bennet. Includes bibliographical references (leaves 311–338).

- Was, Daniël A., "The land-tenure texts from Hagia Triada", Kadmos, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 91-101, 1978

- Was, Daniel A., "The land-tenure texts from Hagia Triada", Kadmos, vol. 20, no. 1-2, pp. 7-25, 1981

External links

[edit]- Cracking the Cretan code Ester Salgarella AEON 2022

- The mathematical values of Linear A fraction signs – Science Daily – September 8, 2020

- Interactive database of Linear A inscriptions Description

- Mnamon: Antiche Scritture del Mediterraneo (Antique Writings of the Mediterranean)

- GORILA Volume 1

- Linear A Explorer